Erratum : Correction to Report

Date: March 18, 2024

We would like to bring to your attention a correction to the report, Aging and Dying in Prison: An Investigation into the Experiences of Older Individuals in Federal Custody, published on February 28, 2019. A calculation error was identified in the “Regional and Institutional Inmate Population by Age” table in Annex A, which has since been corrected as of February 12, 2024. Please note that this correction does not impact the findings, nor the recommendations presented in the report.

Although the necessary changes have been made to the HTML and PDF versions of the report, we regret that the correction could not be applied to the print publication. We apologize for any inconvenience this may have caused.

Should you have any questions or require further clarification, please do not hesitate to contact our office at org@oci-bec.gc.ca.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Methodology

Background

Finding 1: Some older, long-serving offenders are being warehoused behind bars

Finding 2: Failure to recognize and protect a vulnerable population

Finding 3: Prisons were never intended as facilities for older persons

Finding 4: As the number of inmates with chronic disease rises, so do correctional health care costs

Finding 5: Prison is no place for offenders who require end-of-life care

Finding 6: Lack of adequate and humane release options

Finding 7: Community alternatives are lacking and are not well resourced

Finding 8: Need for a comprehensive and funded national strategy

Conclusion

Summary of Major Findings

Summary of Recommendations

Annex A: Detailed Statistical Tables and Graphs

References

Introduction

Prisons were never intended to be nursing homes, hospices, or long-term care facilities. Yet increasingly in Canada, they are being required to fulfill those functions. The proportion of older individuals in federal custody (those 50 years of age and older) is growing. They now account for 25% of the federal prison population (3,534 individuals 50+; 3,432 men and 102 women of a total prison population of 14,004). This demographic has increased by 50% over the last decade alone. Rising correctional health care costs, palliative care, and higher incidence of chronic disease reflect, at least in part, the impacts of a population that is aging behind bars. In some cases, keeping them behind bars is neither necessary, appropriate nor cost-effective. Yet there are currently few community alternatives for this vulnerable segment of the prison population. Many older individuals in federal custody seem to be languishing behind bars. Their sentences are no longer being actively managed, and there are little or no interventions to assist in their rehabilitation and return to the community.

In so far as older individuals in federal custody are concerned, this joint investigation by the Office of the Correctional Investigator (the Office) and the Canadian Human Rights Commission (the Commission) finds a general failure on the part of the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) to meet the fundamental purposes of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act ( CCRA ): safe and humane custody and assisting in the rehabilitation and reintegration of offenders into the community.

The conditions of confinement of older individuals in federal custody are lacking in terms of personal safety and dignity, and the prospect of these individuals returning to the community is often neglected and overlooked, all of which jeopardizes the protection of their human rights. The findings of this investigative report show that CSC’s treatment of older individuals in federal custody does not respect their human rights; is not justified in terms of institutional security or public safety; is inconsistent with the administration of lawful sentences imposed by courts, and; is unnecessarily costly to Canadians. CSC is falling short of ensuring that correctional interventions and services meet its obligations to respect and protect the inherent dignity, characteristics, needs and rights of older individuals in federal custody.

Under the Canadian Human Rights Act , the CSC is a service provider with an obligation to provide correctional services that respect people’s characteristics which may require CSC to accommodate their needs related to prohibited grounds of discrimination in the Act, including age and disability, and also the intersection of more than one ground of discrimination (e.g. sex, gender identity or expression, race, national or ethnic origin, disability). This obligation is bolstered by section 4(g) of the CCRA, which requires CSC to ensure that correctional programs, policies and practices respect differences and respond to the special needs of offenders including those related to prohibited grounds of discrimination. CSC must ensure that respect for differences related to prohibited grounds of discrimination is reflected in the design and delivery of correctional services (including correctional policies, programs, practices and facilities). Based on case law from the Supreme Court of Canada, it is clear that CSC has an obligation to not only be aware of differences between federal offenders related to prohibited grounds of discrimination but also to “build conceptions of equality” into correctional services as far as reasonably possible. CSC’s duty to accommodate the needs of older individuals may be limited by considerations of health, safety and cost where those considerations lead to undue hardship, but CSC bears the burden of demonstrating undue hardship.

Scope of the Investigation

The Office and the Commission together launched this investigation to give a 'voice’ to older individuals in federal custody, some of whom have spent the greater part of their lives locked up. The findings of this investigation rely upon interviews conducted with more than 250 of these older individuals, who told their stories and brought forward their concerns. Hearing directly from older individuals is key to better understanding their experiences, challenges, and vulnerabilities, as well as the ways that the system could be improved for them. Interviews with individual older persons provided perspectives on the correctional system that can only be revealed through their eyes and their lived-experience.

This joint investigation focused on the following objectives:

- Provide an overall statistical profile and assessment of correctional outcomes of all offenders aged 50 and over in federal custody and released to the community. Additional statistics for those 65+ are also provided, including chronic disease prevalence and mental health status.

- Gather information from older individuals in federal penitentiaries and those released and supervised in the community about their correctional experiences, challenges and vulnerabilities.

- Assess and review policy, practices and actions taken by CSC to respond to the needs of this segment of the prison population (i.e. programming; education; employment; healthcare; release planning and reintegration; palliative and end-of-life care; and compassionate release).

- Scope and assess the supervision and accommodation practices in the community to safely and successfully reintegrate older individuals.

- Consider the characteristics, needs, conditions and experiences of individuals 50 years of age and older in federal custody from a human rights and dignity perspective (e.g. discrimination including ageism; accommodation; and accessibility).

- Identify domestic and international best practices that may be useful in better managing older individuals in federal custody.

Partnership between the Office of the Correctional Investigator and the Canadian Human Rights Commission

This investigation was jointly conducted by the Office and the Commission. Both the Office and the Commission bring significant expertise to this investigation. The Office has been monitoring and tracking the challenges of older offenders for more than a decade and the Commission brings expertise with respect to human rights and disability, accessibility, discrimination and ageism. Collaboration between the two organizations was essential to better understand how best to ensure public safety while respecting and protecting the unique needs, dignity and rights of older individuals in federal custody. The two organizations are uniquely positioned to assess the vulnerabilities of this segment of the prison population and identify areas where changes in organizational policy and practice are required. Staff from both organizations worked in close collaboration conducting interviews, reviewing literature and data, and the developing of joint findings and recommendations.

The benefit of this partnership was the ability to assess the conditions of confinement, physical environment and experience of older persons in federal penitentiaries from a human rights and human dignity perspective. Partnerships such as this are important examples of how independent agencies, such as the Office and the Commission, can bring expertise and different perspectives together to examine an issue, report on findings and make informed recommendations that stem from collaboration, insight, access and expertise.

Correctional Investigator of Canada

Chief Commissioner

Canadian Human Rights Commission

The Office of the Correctional Investigator serves Canadians and contributes to safe, lawful and humane corrections through independent oversight of the Correctional Service of Canada by providing accessible, impartial and timely study of individual and systemic concerns.

The Canadian Human Rights Commission is an independent organization whose mission is to ensure that everyone is treated fairly, no matter who they are. The Commission protects the core principle of equal opportunity by promoting a vision of an inclusive society free from discrimination and by protecting human rights through a fair and effective complaints process.

Methodology

Defining an older offender

Establishing a working definition of what constitutes an older offender is challenging and definitions vary throughout the literature, ranging from 45 to 65 years of age. 1 In Canadian society, we often refer to those who are older or aging as individuals who have retired from the workforce, are receiving an old age pension or who are showing the physical effects of aging (generally 65 and over). Research shows that those admitted to federal custody often have poorer overall health, including higher prevalence of chronic and infectious diseases, than the Canadian general population. This is often a result of the life these individuals have led before coming into custody (e.g. substance abuse, lack of medical care, inadequate diet, mental health issues, homelessness, poverty). The overall health of those in a prison environment often mirrors the health conditions of individuals that may be up to ten years older in chronological age. 2 However, not all accept the notion of accelerated aging in the prison environment 3 as it is also possible that better access for some to physical and mental healthcare in the prison environment mitigates the impact of accelerated ageing.

Finally, the term “age” is not defined in the Canadian Human Rights Act . From a human rights perspective, age is a concept that must be interpreted and applied contextually. Given the adverse life experiences of many offenders and the negative impacts of prison on health, there is a need to understand the significance of age differently in this subpopulation of offenders and this must inform CSC’s human rights obligations.

Investigative Plan

The investigation employed a research and analytical strategy involving several distinct, but related components:

- Review of relevant literature related to aging and risk profile, and alternatives to incarceration.

- Quantitative data analysis of all individuals 50 years of age and older serving a federal sentence (2 years or more) in a penitentiary or those released to the community on day parole, statutory release or a long-term supervision order (CSC Data Warehouse was used for most of the statistical analysis).

- Individual investigative interviews were conducted by the OCI and the CHRC. Questions focused on areas such as access to programs and services, social activities, personal safety, conditions of confinement, health care, accessibility, use of force, and segregation.

- Individual, on-site interviews (voluntary and confidential) conducted with individuals 50 years of age and older in federal custody, as well as with CSC staff. Interviews were conducted between March 2018 and June 2018. This series of interviews spanned all five CSC regions at nine separate institutions. Interviews included individuals classified as minimum, medium and maximum security:

- Ontario: Bath Institution, Grand Valley Institution for Women

- Pacific: Pacific Institution/Regional Treatment Centre, Mission Institution

- Prairie : Bowden Institution, Pê Sâkâstêw Centre (Indigenous Healing Lodge)

- Atlantic: Dorchester Penitentiary

- Quebec: Joliette Institution for Women, Federal Training Centre.

- On-site interviews were conducted with men and women who have been released to the following (non-CSC run) community-based residential facilities (CBRFs), as well as some of the staff: 4

- Haley House (Peterborough, Ontario)

- Maison St-Léonard Community Residential Facility and Service Oxygène Satellite Apartments (Montreal, Quebec)

- Kirkpatrick House (Ottawa, Ontario)

- Thérèse-Casgrain Halfway House (Montreal, Quebec)

- Community Residential Center of the Outaouais (Gatineau, Quebec)

- In total, individual interviews were conducted with:

- 250 older individuals incarcerated in a federal penitentiary (men: 210 and women: 40).

- 18 inmate caregivers who provide support to older individuals in federal custody.

- 12 older individuals released to the community residing in a CBRF (men: 6 and women: 6).

- 41 CSC staff members (Wardens, Assistant Warden Interventions, Chiefs of Health Care, nurses, correctional officers, parole officers, correctional managers).

- 14 CBRF staff.

- A review and assessment of CSC research, policy, services and interventions.

- Consultations with other organizations/groups: St. Leonard’s Society of Canada; Dementia Justice Canada; the Parole Board of Canada; Executive Director at St. Leonard’s House Windsor (Windsor, ON) and two retired CSC employees (Warden and Chaplain), who were part of establishing the psycho-geriatric unit at the Regional Treatment Centre in the Pacific region.

- A review of publicly available policies and practices associated with how correctional authorities in other countries manage their older prison population. In addition, information was requested from international correctional authorities and responses were received from the United Kingdom, Finland, Norway, Australia and New Zealand.

Background

Profile of Older Individuals in Federal Custody 5

According to the most recent 2018 data, 25.2% of the federally incarcerated population is 50 years of age and over (20.2% are aged 50-64; 4.1% are aged 65-74; and 0.9% are 75 years of age and older). 6 By comparison, nearly 4 in 10 Canadians are 50 years of age and older and 16.1% of the Canadian population is 65 and over. 7 As of November 2018, the oldest male in federal custody is 87 years old, and the oldest female is 79. The average age of federal offenders (including those incarcerated and released to the community) has been gradually increasing and is now 40 years. 8

CSC states that growth rates for those 50 years of age and older (including those 65+) have been linear and constant (and perhaps even predictable) for the past 5 years, and that their representation in custody is not as high as the general Canadian population. 9 While both statements are technically true, it is the growing concentration of older individuals in federal custody—being housed in facilities that were not designed to hold them in the first place—that makes this an area of increasing attention and concern, one that underscores the unmet needs of a largely hidden and neglected population.

Aside from larger demographic trends in Canadian society, there are some unique factors driving the increase in older individuals in federal custody:

- One in four (26.4%) federal inmates is serving a life or indeterminate sentence. Half (50.3%) of individuals 50 years of age and older in federal custody are serving a life sentence. 10 Some long-serving inmates have been incarcerated for three, four or even five decades. The accumulation of 'lifers’ creates a stacking effect over time. Many inmates have become elderly or even geriatric or palliative behind bars.

- Individuals in federal custody age 50 and older are more likely to be serving a longer than average sentence (more than 6 years for those with a determinate sentence). 11

- More individuals are being sentenced later in life. Convictions for historic offences (often sexual offences) have also impacted on the age at admission. Since 2000–01, 12 the proportion of federally sentenced offenders 50 years of age and older admitted on a warrant of committal (where it was their first federal sentence) has doubled—increasing from 8.2% to 16.4% in 2017–18. 13

- Since 2005, the number of offences with mandatory minimum penalties increased considerably. 14

Among the total population of individuals in federal custody 50 years of age and older, there are three main sub-groups capturing the majority of older offenders: 15

- Long-term first-time offenders (defined as those with a first conviction that occurred prior to 50 years of age, who are serving sentences of 10+ years). This group is aging or growing old behind bars primarily as a result of a long or indeterminate sentence. They represent 24% of the older prison population.

- Those convicted later in life (defined as those with a first conviction after 50 years of age). This group comprises approximately 28% of the older population.

- Recidivists who often spend many years moving in and out of incarceration (defined as those who previously served at least one federal sentence). This group represents 45% of the older population.

In 2017–18, when compared to younger individuals (< 50) in federal custody, older individuals (50+) were more likely to:

- Be serving a longer or indeterminate sentence;

- Be convicted of a sexual offence;

- Be classified as minimum security;

- Have a high level of risk;

- Be deemed a dangerous offender; and,

- Be admitted to segregation for their own safety.

Over the past decade, the number of federally sentenced women 50 years of age and older has nearly doubled—from 56 in 2007–08, to 102 in 2017–18. The most recent 2018 data shows that 89 of the women in federal custody are between the ages of 50 and 64. This represents 13.5% of all women in federal custody. 13 women (2%) are 65+ years of age.

Similarly, over the past decade, the number of Indigenous individuals in federal custody 50 years of age and older has also increased. The number of older Indigenous persons has more than doubled—from 265 individuals in 2007–08, to 632 in 2017-18. (Ages 50-64: 534 or 13.9%; age 65 and older: 98 or 2.5%). The number of Indigenous individuals 50 years of age and older has increased every year since 2007–08.

The supervised population in the community is also aging (i.e. those in halfway houses or community correctional centres, on parole, statutory release or a long-term supervision order, etc.) Between 2008–09 and 2017–18, the community population 65+ more than doubled—from 544 offenders in 2008–09, to 1,119 in 2017-18. In 2017–18, nearly two-thirds (63.5%) of those 50 years of age and older released to the community were on full parole; another 17% were on Statutory Release; 13.4% were on day parole; and 6% were released on a long-term supervision order.

Health Profile 16

CSC recently reviewed the prevalence of chronic health disease of all offenders 65+ identified from the Offender Management System (October 2, 2107). 17 This included an examination of the records of 721 adults 65+ in federal institutions. Overall, preliminary findings suggest that the prevalence of chronic disease among individuals 65+ in federal custody is generally higher than that of the general Canadian population (age 65+). The most prevalent chronic diseases among offenders 65+ appear to be obesity, hypertension, high cholesterol, type II diabetes and chronic pain.

In terms of mental health profile, individuals 65+ in federal custody appear to have high rates of depression, anxiety and personality disorder.

The CSC review also found that 112 offenders age 65+ have a current cancer diagnosis (e.g. prostate, gastro, skin, lung, bladder, kidney, lymphoma, etc.). Medications are most frequently prescribed for those 65+ for hypertension, cholesterol, anticoagulant, gastroesophageal reflux disease, antidepressants and diabetes. Not surprisingly, many individuals 65+ in federal custody are being prescribed multiple medications.

Little Progress to Date

The growing number of older people under federal sentence is not a new issue for Canada. CSC completed its first comprehensive review of this issue in 2000. At that time, 13% of the inmate population was 50 years or older. Issues identified then included rising health care costs, specialized care, assistance in daily routines, palliative and chronic care and community release strategies for older offenders. An Older Offender Division was created at CSC National Headquarters with a specific mandate to address these issues. 18

The Office first raised the issue of older offenders in its 2005–06 Annual Report. The Office's 2010–11 Annual Report examined the issue in more depth (at that time the in-custody offender population of 50 years or older was just under 20%), highlighting the challenges and vulnerabilities facing this group and recommended that CSC develop a more appropriate range of programming and activities, hire more staff with training and expertise in gerontology and implement a national older offender strategy. The Office has updated and repeated these concerns and recommendations in successive Annual Reports.

In terms of legislation and policy, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act ( CCRA ) and Regulations ( CCRR ) do not explicitly specify age (or being older) as one of the factors to consider in correctional programming, policies or decision-making. Section 4(g) of the CCRA , however, states that “Correctional policies, programs and practices respect gender, ethnic, cultural and linguistic differences and are responsive to the special needs of women, aboriginal peoples [sic], persons requiring mental health care and other groups ” [emphasis added]. CSC has instituted a number of measures in response to the growing number of older individuals and issues of accessibility more broadly in federal custody including:

- allocating ranges dedicated primarily to older individuals;

- developing an Assisted Living Unit at Bowden Institution and a psycho-geriatric unit at Pacific Regional Treatment Centre;

- reviewing the prevalence of chronic diseases among older inmates;

- creating a caregiver program at some institutions;

- retro-fitting institutions (e.g. ramps, accessible washrooms); and,

- conducting research to examine the older offender population.

While both the Office and the Commission acknowledge that these local and regional measures are a good start, they fall significantly short in several ways. First, these CSC measures are not nationally integrated. Second, they are impeded by a lack of acknowledgement in policy and practice that older individuals constitute a vulnerable group in corrections who require specially adapted or tailored services and interventions. As well, there are no national policy directives or guidance specific to the care and management of older individuals in federal custody. Moreover, until recently, CSC has made little attempt to assess or recognize the needs of older individuals in federal custody as separate or distinct from the rest of the offender population.

In fact, until just recently, CSC maintained that its current measures—premised on an assessment of an individual’s ability to perform basic daily living activities—are adequate to address the needs of all offenders, even older individuals.

This past year, following repeated recommendations by the Office for a National Older Offender Strategy, including the Office’s 2015–16 Annual Report, CSC finally agreed to develop a framework that addresses the care and custody needs of older offenders. This initiative, which the Service committed to implement by March 31, 2018, is still in draft form and has not been released publicly.

Delivery on this commitment, which in draft documents is framed as “promoting wellness and independence of older persons within CSC” is underway. It involves extensive stakeholder, expert and offender consultations in several areas of service delivery. As part of this investigation, the Office received and reviewed a draft (May 2018) CSC document entitled, “ Promoting Wellness and Independence of Older Persons in CSC Custody: A Policy Framework .” As described in that document, CSC’s approach to older individuals in federal custody is to support them in remaining functionally independent as long as possible, and to allow them to “age in place.”

While the framework and initiatives proposed in it will certainly better assess and identify gaps and needs within the older offender population, as well as improve internal processes and the situation of many older offenders, the Office and the Commission believe the proposed framework is too narrow, and does not go far enough. Nearly all of the proposed initiatives, while important and required, are focused on helping older individuals better function within the prison walls. There is virtually no mention of using the findings from the cognitive and functional assessments recently conducted by CSC on individuals 65+ to determine if a placement in the community might be more appropriate. While CSC describes initiatives to connect older individuals leaving prison with community services, there is still no practice to assess whether older individuals within prison, including those with health deterioration, could be placed in more appropriate facilities in the community. In other words, CSC’s proposed plan seems to leave older individuals in federal custody to effectively “age in place,” within the existing prison environments and infrastructures. CSC’s proposed approach is to offer more tailored interventions only as an individual’s functionality (and independence) progressively deteriorates over time. Keeping inmates who are in declining health in prisons, which need to be retrofitted with specialized equipment and resources (e.g. lifts, hospital beds, medical specialists), could entail significant costs.

Some of the older offenders that the Office and the Commission interviewed for this investigation are mobility impaired (wheelchair user), and have difficulty communicating as result of advanced dementia/Alzheimer’s disease and/or declining motor skills. Some of them are not aware of their surroundings or why they are even in prison. Surely, some of these individuals would be better served in a community facility designed and adapted to meet their needs. A community placement would not only be significantly less costly, but would undoubtedly provide more dignity and better care.

Many individuals who have experienced advanced health-decline have spent several years behind bars and some are now chronically or terminally ill. The risk that some of these individuals present to society seems negligible. The resources that CSC is spending to keep this segment of the population behind bars could be better used to fund alternatives in community long-term care facilities. CSC’s proposed “aging in place” approach does not seem to adequately consider alternatives to incarceration that may offer more dignified, less costly and safer alternatives to unnecessary incarceration.

An important final note

The older population in federal custody is a very diverse group of individuals with different characteristics, needs, challenges and experiences. The information gathered in this joint investigation affirms that older offenders frequently experience adverse impacts, barriers and challenges that result from more than one ground of discrimination. This is referred to as intersectional discrimination. It produces unique and, at times, compounded disadvantage that is different from the discrimination that can result solely from age.

In particular, while age and disability are separate concepts, they intersect uniquely in this sub-population. For example, while not all age-related limitations may be considered disabilities, they can result in functional impairments and their progress and impacts may be heightened in the prison environment. As noted, this investigation gathered some information regarding the differences between older offenders based on disability and sex, however, it is clear that characteristics relating to other prohibited grounds in the Canadian Human Rights Act , including “gender identity or expression,” “race,” or “national or ethnic origin” (both which frequently are identified as relating to Indigeneity) are other important considerations in this group of offenders.

The findings of this investigation suggest that there is a need to more closely examine and consider the intersectional characteristics and needs of offenders. Together, the Office and the Commission urge CSC to do so in its development of a National Older Offender Strategy. CSC has an obligation to recognize, respect and be responsive to the diversity within this sub-population of individuals within the correctional system.

Finding 1: Some older, long-serving offenders are being warehoused behind bars

“The purposes of a sentence of imprisonment or similar measures deprivative of a person’s liberty are primarily to protect society against crime and to reduce recidivism. Those purposes can be achieved only if the period of imprisonment is used to ensure, so far as possible, the reintegration of such person into society upon release so that they can lead a law-abiding and self-supporting life.” (Rule 4: United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules))

In our interviews with older individuals in federal custody, it was surprising to learn that some individuals have been behind bars for three, four, or five decades. Many are years or even decades past their parole eligibility dates. 19 It bears remembering that a life sentence in Canada for first degree murder is 25 years before parole eligibility, though many serve longer than 25 years before being granted parole. Some are never released.

A survey released in September 2017, indicated that in terms of statutory life sentences from 98 countries, the average minimum period was 18.3 years (the median was 18 years and the mode was 15 years). 29 countries (30%) set their minimum period at 25 years or more, a category that includes Canada. The minimum period was 15 years or less for nearly half of the sample. 20 In other words, in terms of sentence length, Canada’s minimum life terms rank on the high end in terms of international comparisons.

In every case where a life sentence is imposed, it is important to understand that parole eligibility does not necessarily mean release . Even if paroled, a 'lifer’, with an indeterminate sentence remains under sentence until death. In all instances, a life sentence in Canada is for life, even if that person is eventually released and supervised in the community.

Today, there are more than 3,600 individuals (or 26.4%) in federal custody with a life sentence. 21 Though the number of new admissions to federal custody with a life/indeterminate sentence has remained relatively stable over the past decade, the accumulation of 'lifers’ over time creates a stacking effect. In other words, many individuals in federal custody age and become elderly or even palliative behind bars as they serve their sentence. Over the past ten years, life-sentenced offenders constituted less than 4% of all persons admitted to federal prison each year, but collectively they now represent one quarter of the total inmate population. 22

Among individuals in federal custody 50 years of age and older, half (50.3%) are serving an indeterminate sentence. Four in ten federally sentenced women 50 years of age and older, and nearly six in ten (58%) Indigenous individuals 50 years of age and older are serving indeterminate (life) sentences. 23

Based on sentence length or time-served to date, there are a number of individuals who have aged behind bars. In many cases, long periods of incarceration may no longer meet the purpose or original intent of the sentence and may not be necessary from a public safety perspective. In addition, long periods of incarceration may, in some cases, be inconsistent with respect to human dignity.

Consecutive life sentencing legislation passed December 2011 in Canada, 24 means that some offenders will spend the rest of their natural life behind bars. For the first time in Canada, this legislation imposes a living death sentence with no actual prospect of release. The age-related adverse consequences of these legislative provisions are significant and need to be considered.

Long-Serving Older Inmates*

Currently, in Canadian federal penitentiaries, there are 316 inmates 50 years of age and older who are on their first federal sentence, have not yet been released and have spent 20 years or more behind bars; 199 have been inside for 25 years or more, 125 have been in for 30 years or more and 24 for 40 years or more. Approximately 12% of those age 50+ who have spent 20 years or more in prison have a 'dangerous offender’ designation.

When individuals on their second or greater federal sentence are considered, just shy of 600 individuals 50 years of age and older have spent (though not consecutively) 20 years or more in federal prisons, 325 have spent 30 years or more and 107 have been imprisoned for 40 or more years.**

* Data extracted from CSC Data Warehouse, May 2018.

**Many of the individuals who have consecutively accumulated 20 years or more in prison may have spent significant periods of time in the community under supervision before going back to prison. This analysis counts only time spent in a federal institution. Many individuals will have accumulated prison time in provincial jails as well, which is not counted here.

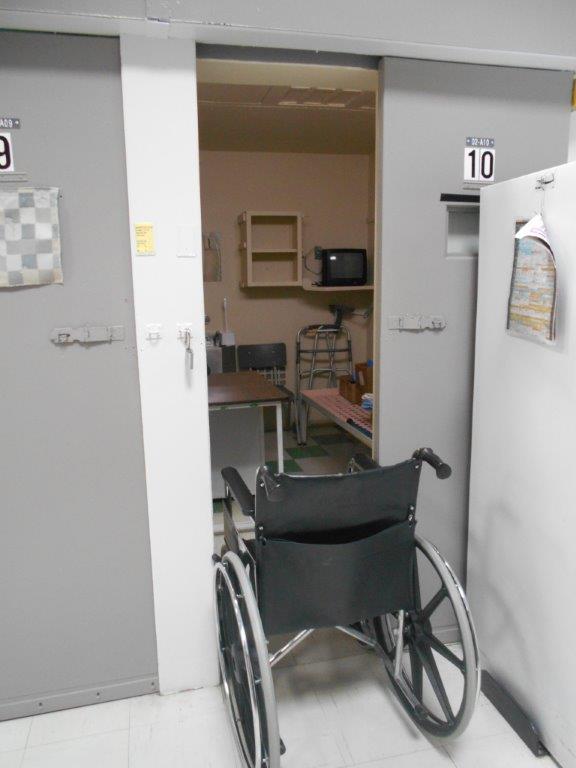

Social Isolation

Isolation and monotony are amplified for those with serious mobility/health issues. One individual who was quite elderly and had cognitive and mobility challenges (he was in a wheelchair and was starting to show signs of dementia) reported that his day consisted of being wheeled out into the common area in the morning where he was left at a table by himself (unless someone came to visit him at the table), returning to his cell at lunch time, attending the library to read the newspaper for two hours each day and then returning to his cell for the remainder of the day to sit in his wheelchair or lay in his bed. He attends mass every Sunday and has a visit from the Chaplain once a week.

After spending long periods behind bars, many of these individuals have very little to show for it in terms of reintegration. Other than working, many reported engaging in very few meaningful or purposeful activities since they long ago completed any required correctional programming or upgraded their education. For those who are not working, they described their days as long, lonely and boring. Many reported watching television and/or sleeping during the day. Social programming activities (e.g. library, hobby shop, gym, card room, poolroom) are usually closed during working hours to facilitate institutional routines and work schedules. One inmate, age 58, told us: “During the day, we just mill around. Many guys do nothing here; for them, they are just existing.”

Many reported that they rarely meet with their institutional parole officer. Little, if any, substance remained on their correctional plan. Though past retirement age, many choose to continue working only because the alternative is being locked up or isolated in their cells.

Spending long periods behind bars can contribute to eroding ties and bonds with family and friends, factors which are important and can assist in community reintegration. Some inmates told us they have lost contact with their family and friends after spending many years or even decades behind bars. They may have passed away, cannot afford to visit, find it too difficult to visit because of their own health or the distance to be travelled, or are no longer interested in maintaining ties.

The impact of constantly changing parole officers on a 'lifer’

In December 2014, Bill C-483, An Act to Amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) ( Escorted Temporary Absence ) amended the CCRA to limit the authority of the institutional head to authorize the escorted temporary absences (ETA) of an offender convicted of first or second degree murder. It requires that ETAs for such offenders instead be authorized by the Parole Board of Canada (PBC).

During interviews, a 'lifer’ who has been incarcerated for 36 years told us about how he had been approved for many ETAs, however when Bill C-483 came into effect, he was required to go before the PBC in order to be approved to continue participating in ETAs. But in order to get a hearing, his correctional plan had to be updated. And in order to do that, he required a psychological assessment. After changing parole officers several times (he reported he had 8 different parole officers over a period of five years), it took him a year and a half to get a psychological assessment and a further two years for yet another parole officer to update his correctional plan. However, by the time his Correctional Plan had been updated, his psychological assessment had expired (it is only valid for 2 years). He has now waited three and half years to resume his ETAs. Given the importance of ETAs in demonstrating reintegration potential, this is unacceptable.

One inmate, age 78, told us that CSC has “…no strategy for lifers — I finished my programming in the first two years and now I am doing nothing.” Another inmate, age 77, said: “I am sick and tired of doing time. I have no information and no answers about what I’m supposed to do. My parole officer doesn’t know. I want to get out of here and move on.” Another inmate, age 66, reported: “I have no understanding of what CSC expects from me to reduce risk … If you are quiet, you are put on the back burner and forgotten about.”

Many reported having several parole officers over a number of years (i.e. one reported 14 different parole officers over 10 years; another 6 over 2 years). In CSC policy, a security classification review is supposed to be completed at least once every two years for inmates classified as maximum or medium security. It is difficult to comply with this policy when an individual is consistently assigned to a new parole officer who must spend time getting to know their new clients before recommending them for a lower security classification, programming, or escorted temporary absences (ETA) /unescorted temporary absences (UTA). Those who have spent many years behind bars would seem to require additional and consistent support, programming, services, ETA/UTAs or work releases to help them safely reintegrate.

Not surprisingly, many of the older individuals in federal custody we interviewed told us they felt that they have become 'institutionalized’ and that it would be very difficult returning to the community. As one long-serving inmate put it: “I’m institutionalized. I’m bitter and I have been screwed over by the system so badly, I’ll never function on the outside.” He is 68 years old. Another individual, age 55, told us: “It’s mental — you’re told to do everything in prison, you’re out of touch with the world.”

Many of them appear angry and bitter, telling us that “…the system is broken.” Some feel that they have been 'forgotten’ about or perhaps “put to the bottom of the pile” because they no longer complain and are not involved in institutional incidents or make much of a fuss about anything.

Many expressed very little interest in continuing to “fight” the system. Few bother to put in requests, complaints or ask to meet with their parole officer because “… there is just no point.” For these men, there seems to be very little incentive to continue to progress toward eventual release. There is a sense that they have been overlooked or abandoned. Many of those interviewed have significant mobility issues or serious chronic illnesses and could likely be safely managed in the community.

On a final note, our investigation suggests that older individuals (particularly those who have been in the system for extended periods) face stigma and stereotyping resulting from unconscious or conscious beliefs that they cannot be rehabilitated or reintegrated —or that they are not worthy of the expenditures of resources to do so. While not necessary to demonstrate discrimination, stigma and stereotyping are indicators of discrimination. To the extent that stigma and stereotyping against this population are contributing factors to warehousing and institutionalization, they represent a systemic and pervasive form of discrimination that requires CSC to take proactive measures. Attitudes and approaches to the management of older individuals in federal custody need to change.

What is Institutionalization?

In prison, an inmate’s choices and decisions are narrowed resulting in a gradual habituation to the prison environment (Crawley, E., & Sparks, R., 2006). Over time, an inmate’s life becomes highly routinized and predictable, and is gradually overtaken by institutional norms. Consequently, long-term incarceration can lead to a sort of “institutional dependency,” or “institutionalization,” defined as: “the incorporation of the norms of prison life into one’s habits of thinking, feeling, and acting.” (Haney, C., 2002) The effects of institutionalization seem to be greater for inmates who enter prison life at an earlier age.

Institutionalized inmates have been characterized by the following psychological adaptations:

- lack of interest in the outside world or in “starting afresh”;

- anxiety about release;

- social alienation and withdrawal;

- hypervigilance, suspicion, and interpersonal distrust;

- diminished sense of self-worth and personal value;

- inability to make independent decisions;

- incorporation of exploitative norms of prison culture;

- dependence on institutional structures and contingencies; and

- Post-Traumatic stress reactions.

Recommendation 1:

We recommend that an independent a review of all older individuals in federal custody be conducted with the objective of determining whether a placement in the community, a long-term care facility or a hospice would be more appropriate.

Finding 2: Failure to recognize and protect a vulnerable population

CSC is failing to recognize older individuals in federal custody as a vulnerable population within the prison population. As a result, their health, safety and dignity are not being adequately protected. These omissions show up in simple, everyday living and broader systemic issues.

For example:

- Older inmates, some of whom are past retirement age, are still expected, required or compelled to work only out of fear of the alternative—being isolated, locked up, or at risk of being put on a reduced allowance.

- Older inmates voluntarily request to be placed in segregation more frequently and most commonly out of fear for their personal safety.

- Some use of force incidents and physical restraint methods (e.g. wristlocks and ankle shackles) involving older inmates seem disproportionate and not appropriately adjusted for use on older individuals and the risk they present.

- The incidence of bullying, victimization, intimidation and assaults on older inmates appears commonplace. Incidents went largely unreported and were therefore rarely investigated or addressed.

- There is a need for reasonable access to dignity aids and comfort items for older inmates (e.g., medical mattresses, pillows, and orthopedic shoes).

Death of an Older Individual during an Extended Lockdown

A medium security institution was locked down for nine days because of a search under section 53 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act . During the lockdown, security staff received a 'kite’ (anonymous note) indicating that an 83-year-old Metis inmate might harm himself and was refusing meals. He had refused solid food for six days without CSC staff noticing. As a result, the inmate was placed on a fifteen-minute watch for the rest of the night shift. The next morning, the officer in charge of the watch opened the cell door to speak with the inmate and found him to be pale, breathing heavy, refusing to eat and making comments about wanting to die. Following an assessment by a nurse, the inmate was to be moved to the Regional Treatment Centre, however while being escorted to the van, officers decided it was not safe to transport him given his health condition. While trying to remove him from the van, the inmate went limp. Initial first aid was provided, including the AED and 911 was called shortly after and the inmate was transported to the hospital. He died in hospital two days later.

Lengthy lockdowns are tantamount to placement in segregation with limited to no movement, fresh air or human contact. This lockdown was particularly difficult as it occurred during a heat wave exacerbating the already difficult conditions of confinement. It is essential that vulnerable populations (i.e. older offenders, those with mental and/or physical health issues) are monitored daily during lockdowns by professional health care staff.

Personal Safety

Though some older individuals in federal custody reported feeling safe in their environment (primarily those in minimum security institutions), many others reported having experienced bullying or muscling from younger inmates for canteen items or medications. This was overwhelmingly reported in men’s institutions. Some feel so vulnerable that they rarely leave their cell or range, and some do so only if they absolutely have to. They feel especially vulnerable in common areas such as the cafeteria and yard where they report incidents of muscling for a chair or their food. “What am I going to do when a younger guy cuts in front me? I just don’t say anything.”

During another interview, an elderly man was noticed by the investigator to be pacing back and forth on the range. The interviewee told the investigator that this older man is too afraid to leave the range and pacing was how he got a bit of exercise during the day. Others reported incidents where they have been physically assaulted, pushed around or beaten up resulting in various types of injuries though few were willing to provide details. Most of these incidents are not reported or investigated by CSC staff.

Canteen Access and Older Individuals

The Office recently received a letter/petition signed by ten older inmates, ranging in age from 62 to 76, identifying issues in terms of access to canteen. In their letter, they stated the following:

“We have basically two options; we can go to the canteen on payday and stand in line for up to two hours, and maybe get through the line to make our purchases, or we can wait a couple of days until we know the line will be smaller – only to find that half the items have been sold out.”

“Another issue is the increased vulnerability of older offenders to pressure or outright force from other offenders (usually gang members) to give up their canteen items, or to buy items to order. I am 68 years old, and I weigh 135 pounds; faced with this kind of pressure from younger, more fit and aggressive offenders, I don’t have too many options. Personally, I have encountered this kind of pressure four times, all in the past three months, with amounts ranging from a dollar or less up to $36.00 (which represents more than a week’s take home pay).”

The letter goes on to make two recommendations: establish a time for older offenders to purchase canteen items and allow older offenders the option to order a bag canteen. This seems like a reasonable compromise, however the institution has denied their requests. Just one institution visited for this investigation (Regional Treatment Centre, Pacific Institution) had set aside a designated time for older offenders to access canteen.

In 2017–18, 13% of victims of inmate-on-inmate assaults 25 were 50 years of age and older. 26 This proportion has risen over the past 5 years (10.8% in 2013–14; 8.6% in 2014–15; 10.5% in 2015–16; 11% in 2016–17).

In 2017–18, of all admissions to segregation for personal safety reasons, including the nature of their offence, 10.2 % involved individuals who were 50 years of age or older. Of those who were over 50 years of age and were admitted to segregation for personal safety reasons, 11 % involved an individual 65 years of age or older and another 89% involved an individual 50-64 years of age. Most older individuals interviewed agreed that they should at least have the option of being housed together. They also felt that careful consideration should be given when younger inmates are integrated into an older population.

Providing older individuals with the option to access canteen and the gym during designated times would provide those who feel vulnerable with a greater level of personal safety and dignity.

Use of Force Involving Inmates 50 years of Age and Older

Prisons often operate with a security-first approach, even for the older population who tend to be more acquiescent and compliant within the institution. The Office reviews all use of force incidents occurring in CSC facilities. The Office recently conducted a pilot project to code all use of force incidents using a variety of indicators. Between October 2016 and October 2017, 1,349 use of force incidents were coded. Of the 1,349 incidents, 124 (9.1%) involved at least one male offender 50 years of age and older. 27 Of those incidents involving an aging offender:

- The largest proportion of use of force incidents occurred at the Ontario Regional Treatment Centre – Millhaven (16 incidents or 13%), followed by Mountain Institution (9 incidents or 7%) and Edmonton Institution (8 incidents or 6.4%).

- Most occurred in a medium security institution (60.4%) versus 33.8% in maximum security and 4.8% in minimum security.

- Nearly one-third (27.4%) occurred in a cell, another 24% on the range and 18% in a common area.

- 64.5% involved physical handling to gain control, 43% involved restraint equipment and 40% involved the use of OC (inflammatory) spray (an additional 9% involved displaying or pointing of an inflammatory agent).

- 20% of use of force incidents resulted in response to an assault between inmates.

These findings highlight the involvement of older individuals in use of force interventions and the high proportion of incidents that involve physical handling. Currently, CSC does not specifically consider an inmate’s age (or related capacity and ability) in its intervention and response model.

CSC also provides limited training with respect to age-related health issues, including dementia or behaviours that might arise from an age-related health condition. A security-based response to a situation arising from an individual displaying signs of aggression who also has dementia would not be appropriate or effective. Training and changes to the use of force policy are required to ensure these situations are managed appropriately.

See Case 5 in textbox below: Use of pepper spray on a 71-year-old male who attempted to hit guards with his cane through the barrier.

Use of Force Incidents Involving Older Individuals

- A 62-year-old inmate who has mental health concerns and uses a cane was physically resisting returning to his cell and was clinging to a doorframe while supporting himself with his cane. One correctional officer took the cane away while the other forcefully pushed the inmate into his cell. The intervention took place with no attempt to negotiate despite the fact that force was not urgently required as there were four officers present, the inmate was not aggressive and posed no threat to others.

- A 71-year-old inmate who uses a walker was waiting at the gate, seated on his walker, to go to Health Services. When the gate opened to let a staff member through, the inmate got up and tried to cross the gate. He then exchanged a few words with the officer at the post and briefly lifted his walker in an intimidating manner before setting it down again. The officer then pepper sprayed the inmate who withdrew behind the gate where he briefly sat down on his walker before returning to his unit.

- A 69-year-old inmate, with identified mental health concerns, did not want to return to his cell for count. The officer approached the inmate, punched him in the chest and grabbed him by his coat collar. There was no sign that the officer attempted to defuse the situation or avoid using force. This use of force was deemed non-compliant by both the institution and regional authorities. This inmate was involved in six use of force incidents over the period of the OCI’s coding project.

- A 52-year-old inmate residing in the psycho-geriatric unit because of a brain disorder was trying to assist a fellow patient in getting a new video game system running. A number of patients were trying to help when the owner of the game system became very frustrated that it would not work. At this point security staff stepped in and asked the inmate with the brain disorder to step away, which he did. Security staff then came over and yelled at him to lock up and he questioned them as to why he needed to lock up. Though he was not aggressive, he was immediately pepper sprayed by security staff. It appears little consideration was given to his cognitive deficits or to alternative ways to diffuse the situation.

- A 71-year-old inmate at a maximum security institution was causing tension with other inmates in the common area. Correctional Officers attempted to intervene and directed the older offender to return to his cell. The inmate began swinging his cane at officers standing behind the unit barrier. OC spray was deployed and the inmate returned to his cell and was later placed in segregation.

Feeling Forced to Continue Working

In Canada, 65 years of age is the point at which people are eligible for Canada Pension benefits (a reduced pension is available at age 60) and Old Age Security. 28 In prison, while “retirement” from work is possible, it is not advisable as there is very little to occupy an offender’s time during the day. Some older individuals in federal custody came into the system very late in their life and have worked a full career in the community or were already retired prior to coming into the system. Nonetheless, they are encouraged to go back to work once in prison.

Most of those interviewed discussed the meagre wages that they earn while working, and their inability to retire within the institution as a result. Many feel “forced” to continue to work just so they could buy themselves a few “treats” from the canteen or save some money for their release. Once an individual retires or is deemed unable to work within the prison, they are put on a basic allowance of just $2.50/day 29 with limited social programming available to them during the day. For those incarcerated in a medium security institution, if they are not working, attending programming or school, they are locked up in their cells for most of the day.

One older individual (55 years of age) we spoke to is paralyzed from the arms down, with just 40% movement in one arm and full movement in the other arm. He experiences constant pain as a result. Nevertheless, he was told by institutional staff that he should work and that they would find something that he was capable of doing.

It is questionable whether requiring—either directly or indirectly—older individuals in federal custody to work is reasonable, or whether being engaged in work should be the only basis for older inmates to obtain a reasonable living allowance. If an older individual wants to work, then CSC needs to consider age-related employment accommodation. If an older individual cannot work, then appropriate activities, time outside their cell, and a reasonable living allowance should be available.

The Office raised the issue of inmate pay in its 2015–16 Annual Report, describing how inmate pay has not changed in nearly 40 years. Inmates are responsible for a greater proportion of the costs to keep themselves fed and cared for behind bars and earn very little once deductions are factored in. In its report, the Office recommended that the Minister of Public Safety initiate a review of the inmate pay system, but the results of this review have not been shared with the Office or been made public.

Recommendation 2:

We recommend that CSC develop a separate and distinct Commissioner’s Directive specific to older individuals, which ensures that their specific needs and interests are identified and met through the provision of effective and adapted programs, services and interventions.

Recommendation 3:

We recommend that CSC provide staff with training in age-related needs — physical, social and psychological — as well as training on how to identify, respond to and appropriately manage behaviour related to dementia.

Recommendation 4:

We recommend that CSC re-examine its use of force training and policy to incorporate best practices and lessons-learned regarding use of force on older individuals (including those using mobility devices).

Recommendation 5:

We recommend that CSC offer appropriate work options (including accommodated options) for older individuals who want to and can continue working. In addition, regardless of whether an older individual can work, CSC should provide a reasonable living allowance to meet personal needs.

Recommendation 6:

We recommend that vulnerable populations (older offenders and those with mental and/or physical health issues) be monitored daily during lockdowns by professional health care staff.

Finding 3: Prisons were never intended as facilities for older persons

“We try to make something new out of the old, and it’s not always easy.”

(CSC correctional officer).

Infrastructure and Accessibility

One of the buildings that investigators from the Office and the Commission visited had a lip on the entryway despite having a long ramp running to the entrance. Those coming to the interviews in a wheelchair had to be “jerked” up and over the lip by their caregiver. As one older individual put it: “wheelchair ramps are in enough locations, but steps and stairs prevail.”

Another individual reported: “Some guys are scared to take showers because there are no grab bars. I also have a scooter. Before the scooter, it was a struggle to get up hills. I was slower to report and that was sometimes a problem. Some of the guards don’t get age-related problems.” (Inmate, age 64)

Across Canada, CSC has 428 wheelchair accessible cells. 30 Of those, 52 are in women’s facilities, and 38 of them are transitional ( e.g. health care beds, segregations cells). All told, it means that CSC has 390 permanent barrier-free cells. This represents 2.5% of all the cells across CSC, which is above the 2% requirement in the Federal Correctional Facilities Accommodation Guidelines for CSC . 31 But accessible cells are just one piece of a larger issue.

Over the years, CSC has made many modifications to improve accessibility (e.g. elevators, lifts, bathrooms with raised toilets and handrails, accessible showers with a removable showerhead, ramps to buildings, poles in cells to assist individuals to pull themselves out of bed, front load washer/dryer). 32 However, given the age, condition and infrastructure of many federal institutions, ensuring comprehensive accessibility will require significant additional investment.

During site visits to a number of institutions, it became clear to investigators that while some cells/rooms may be termed “wheelchair accessible” that did not mean that those using mobility devices could easily move around or fully participate within the institution. For example, investigators noted the following physical barriers and/or infrastructure limitations:

- cells occupied by individuals using a wheelchair where the wheelchair was not able to pass through the cell door;

- doors to buildings without an accessibility button;

- accessible shower stalls often have a lip making it difficult for those using a mobility device to safely access the shower;

- accessible showers without a seat, slip mat or a handheld shower mechanism (one individual fell in the shower while investigators were interviewing and remained there for 20 minutes as there was no emergency button in the shower);

- private family visiting units that are not accessible;

- uneven and broken walkways around the exterior of buildings;

- inclines into housing units and buildings that appeared quite steep;

- lips on entryways to buildings;

- cells without in-cell emergency call buttons;

- kitchen counters that are too high for wheelchair access; and

- health care units lacked wheelchair accessible washrooms and waiting areas requiring older offenders to line up outside regardless of weather conditions.

Winter conditions make outdoor prison grounds even more challenging for those using mobility devices. A few older individuals reported slipping and falling on icy patches and inclines while making their way to health services or the cafeteria. The long distances between the living units and health services, the cafeteria or canteen also create barriers. One 61-year-old individual reported that in the canteen line: “I have to sit on the ground because my back is hurting and it is too far for me to walk.” Situations such as these cause significant mobility challenges for some older individuals. A few reported not going to at least one meal each day because it is just too difficult to get there.

Living Arrangements

In some prisons in the United States, some older offenders may be able to reside in age-specific units. However, there is continuing debate on the merits of this practice. While this model may facilitate the concentration of specialized healthcare services, research indicates that this is not always the case. 33 These units may also lead to isolation or separation from the general population with limited or restricted access to programs and services offered elsewhere in the institution.

Outdated Infrastructure

One unit in a minimum security institution at 600 Montée St-Francois, in Quebec, houses inmates who are amputees (some are double-amputees), others who use oxygen tanks, have Parkinson’s disease or severe diabetes. None of the cells has a safety alarm. Other than by calling out, inmates have no way to communicate if they are in need. The cells are so small that inmates who use wheelchairs must leave them outside. There is no common area so inmates spend the day in their wheelchairs in a narrow hallway with one peer helper moving between them. The building is over 51 years old with poor ventilation. Staff leave the door to the outside open to help with airflow, however as one older individual stated, “I freeze in the winter because the cold air comes straight out on me.”

There are some good examples within CSC of institutions that are providing older offenders with an option to live primarily with others their own age. A number of the institutions visited during this investigation have grouped older individuals together on a particular range or within one or two houses. Many also have designated ranges or houses where they accommodate those who require additional care or have serious health or mobility issues. These houses/ranges are often one level (no stairs), have accessible bathrooms and cells/rooms and are located closer to Health Services (though some are more isolated from programs/services). Many of those interviewed who are living on a range or in a house with mostly older offenders reported that they are relatively satisfied with their accommodations. Many others want to move into such spaces. These experiences suggest that adapted living arrangements need to be expanded and improved upon in terms of accessibility.

Older women, in particular, reported not wanting to be housed with younger women: “Especially at our age, we’re not children anymore. I have life experience. I have needs. Young people don’t care. I’m not interested in listening to their rage or getting involved in their gossip.” Another woman told us: “We’ve raised our children. We do not want to raise more of them.” Then there were other older women who reported that younger inmates were ready and willing to assist them. This range of opinion highlights the need for choice in terms of age-integrated options.

While not common, double bunking (housing two inmates in a cell designed for one) was mentioned a few times by individuals we interviewed. A case was recently brought forward to the Office where a 73-year-old individual had fallen while climbing down from a top bunk in the night to use the bathroom and injured himself. After the Office inquired as to why the younger cellmate had not been assigned the top bunk, the response from the individual who fell was that he was the younger of the two as his cell mate was 84 years of age. At that time, the Office had recommended that the institution consider age as a factor in the cell placement assessment process for double bunking. While this recommendation was accepted, it is noteworthy that neither Commissioner’s Directive 550: Inmate Accommodation, nor the Double-Bunking Cell Placement Assessment – User Guide refer to age as a consideration in determining double bunking assignments.

A Need for Wheelchair Accessible Vans

One elderly woman (66 years of age) reported that she was not able to lift her leg high enough to get into a prison transport van so she asked a correctional officer if one of the cuffs could be removed so she could more easily steady herself. The request was denied. She continued to attempt to enter the van, lost her balance and tried to grab onto one of the correctional officers who stepped back, leaving her to fall to the ground.

A number of older individuals reported instances of trying to get into the prison transport van, often while hand cuffed and shackled at the ankles. One individual reported “…crawling on my hands and knees to get into the van” with handcuffs and shackles (this inmate was dying of heart disease). There were several individuals who discussed difficulties entering and exiting the transport van not only because they are constricted by restraints but also because they have difficulty maneuvering their bodies to get into the small space without assistance. It can be even more challenging for those using mobility devices as these are often taken away making it a struggle to get into the van. The Office has reported before on safety issues related to the transport vans and recommended that they be phased out. 34 Vehicles that can more appropriately accommodate those with mobility challenges should replace these less accessible vans. 35

Likewise, during these medically escorted temporary absences, it seems unnecessary to apply restraints to the legs or hands of an older person that are swollen, painful, easily bruised or cut. The risk of violence or escape that some of these individuals pose seems minimal and could be managed with few or no restraints. After leaving a hospital, one inmate, age 72, commented: “You have your feet in chains and you’re handcuffed. Attached like a sausage, I am sick, where do you want me to go? Plus, the red blanket and four straps on top with two correctional officers.”

Some small concessions would go a long way toward recognizing these concerns. For example, the use of restraints should be proportionate to the actual risk or ability posed by the older offender in the context of their health. 36 CSC has committed to “review the policy on restraint for transportation of older persons for medical care and the use of a threat risk assessment process based on the severity of medical conditions.” 37 The Office and the Commission are encouraged by this commitment.

Barriers to Respect and Dignity

In federal prisons, older individuals are expected to do the same things that a twenty-year-old must do, with few accommodations or exceptions to the rules. Some older individuals in federal custody reported being hurried along and not given extra time to move from one place to another, despite using a walker or a cane. Many reported problems with their feet (pain, swelling) or issues bending over to tie up their shoes. Several want wider shoes (to accommodate swollen feet) or shoes that had Velcro (they are easier to put on and take off). Only a very few were successful in obtaining these non-standard items and only did so after waiting an unreasonable amount of time. One individual (57 years of age) described a situation where his feet were so swollen that he could not fit into his institutional shoes, so he wore slippers instead. While he was afraid of falling using only slippers, he was more frustrated when he was institutionally charged for not wearing standard issued shoes.

In other instances, CSC policies and practices undermine the dignity of older offenders. For example, in one institution, visits by the doctor are limited to the medium security-side of the institution. This means that older offenders housed on the minimum security-side are strip-searched before and after visiting the doctor. Some inmates told us this led them to avoid reporting medical problems that might require a doctor’s care.

At times, institutional routines are also ill-adapted to meet the needs of persons who are elderly and who have disabilities. One older individual explained that because the last stand-up count is at 10 p.m., he has to try to stay awake so that he can get to his cell door, rather than going to bed early.

Other examples highlight the lack of common sense or the extreme inertia of the system in responding to needs within a reasonable period. At a minimum-security facility in Quebec, one individual with Parkinson’s disease has been waiting to go to a halfway house for four years. He resides in a small cell where he is able to get out of bed by balancing between the desk and a pipe on the wall. He cannot go to the halfway house (which is not accessible) until he has knee surgery. He cannot have the knee surgery until he increases his strength. There is no physiotherapist in the institution so he receives no physical therapy. He does not have the strength to get up to use the bathroom at night alone so the peer helper puts incontinence pants on him for nighttime use. A hospital bed has been ordered, but he has been waiting a long time for it. This is unacceptable.

Recommendation 7:

We recommend that CSC designate facilities for older individuals who want to live in such areas—and that such facilities are designed or retrofitted to ensure physical accessibility.

Recommendation 8:

We recommend that CSC create dedicated spaces and times where older individuals can assemble and socialize during institutional working hours, and allow them access to communal prison services during working hours (e.g. library, gym, canteen, visitation, cafeteria, hobby shop and yard).

Recommendation 9:

We recommend that social programs staff organize age-appropriate and disability-appropriate leisure, wellness and recreational opportunities (e.g. stretching, walking, aerobics, yoga, card games).

Finding 4: As the number of inmates with chronic disease rises, so do correctional health care costs

CSC healthcare costs have fluctuated over the past 10 years from a low of $201 million in 2008–09 to a high of $267 million in 2012–13. 38 While healthcare costs are impacted by many factors, the aging offender population is no doubt an important driver of rising costs. CSC does not currently track healthcare costs by age, so it is not known how much is spent per capita on health care for an older person in prison. However, it likely resembles the overall health care trends in Canadian society. 39

Across different countries, older offenders are one of the most expensive age cohorts to incarcerate. Research in Australia and the U.S. have estimated the health care costs of the older prison population to be 2-4 times higher when compared to their younger counterparts. 40 Canada is no exception. It costs, on average, $116,364 per year to keep an inmate incarcerated compared to $31,052 to maintain a sentenced person in the community. 41 Several CSC staff members we spoke to discussed the costs associated with multiple medications that many older individuals in federal custody are prescribed, specialized medical equipment (lifts, specialized tubs and transport vehicles) and the significant overtime costs required to carry out medical escorted temporary absences. At one of the institutions, three of the five beds in the institution’s infirmary are taken up by older individuals who are very ill and had been there for extended periods. One older individual has spent eight years in the prison infirmary, and has become increasingly dependent and bed-ridden. Providing palliative or end of life care in a prison context is excessively costly, challenging and may not be necessary for public safety reasons.

Pain Management Behind Bars

Many of the older individuals in federal custody reported experiencing chronic and sometimes severe pain resulting from cancer or arthritis, and that it is not being well managed by prison health services. A few reported that they were able to get a second mattress, purchase an orthopedic mattress, or get extra pillows to help with their pain, but most were refused these items, and there are inconsistencies across institutions about this. Several individuals have been prescribed Tylenol or Ibuprofen to help alleviate pain, but most stated that the medication was ineffective. Stronger, more effective pain management medications are difficult to get within a prison environment.

CSC’s policy framework for promoting wellness and independence of older persons states that CSC will:

- Review barriers to prescribing narcotics for pain management and continue its pilot project on pain management where a multi-disciplinary team utilizes a range of strategies to address the needs of those with chronic pain.

- Review offender medications with an aim to 'de-prescribing’ medications deemed unnecessary or inappropriate and/or introduce new medications that may improve outcomes.

These are encouraging initiatives that have the potential to help alleviate some of the stress and frustration those with chronic/severe pain reported experiencing.

Specialized Healthcare Units

CSC has established two specialized healthcare units for individuals requiring additional assistance and/or care because of age-related issues. The regional treatment centre (RTC) in the Pacific region has a psycho-geriatric unit with a Peer Assisted Living Program (PAL program) 42 and Bowden Institution has an Assisted Living Unit (ALU) 43 . PAL and ALU clients are housed on the bottom tier with an adapted shower (shower wand, slip resistant flooring, and built-in shower seats), a therapeutic tub, cells are outfitted with a hospital bed, two emergency call buttons located at the door and bed and a built-in grab bar at the toilet. The admission criteria for a PAL/ALU patient includes those who can no longer live safely or independently in a regular institutional environment due to complex health care needs. Though these units have helped many patients function within a correctional environment, several challenges are reported by staff, caregivers and clients alike:

- A lack of 24 hour nursing care.

- Security staff are not suitably selected, nor are they provided with specialized or sensitivity training.

- There is no policy direction (Commissioner’s Directive) specific to these units.

- There is a lack of an oversight or patient advocacy mechanism (e.g., some geriatric clients are completely reliant on CSC staff to manage their health care decisions as they do not have the capacity to form or provide free and informed consent).

A recent external evaluation of the Regional Treatment Centres, 44 commissioned by CSC, and an ethics analysis of the Peer Assisted Living Program 45 support many of the concerns brought forward by staff and clients in the course of this investigation.

The Cases of Two Women Requiring Specialized Care

Investigators were told of a case of a woman who is elderly, possibly starting to show early signs of dementia and who requires the assistance of others to care for herself. She does not currently have a caregiver. Staff and inmates reported that she often hoards canteen items under her bed which attracts insects, goes days/weeks without bathing/showering, rarely cleans her cell and has incontinence issues which are difficult for her to manage on her own. She is unable to cook her own food and while not generally allowed, another woman cooks food for her and staff “look the other way” as they realize how difficult the situation is.

Staff also described a situation where a woman who was palliative and nearing death was kept at the prison despite pleas from staff members to move her to a hospice. She was eventually moved to a hospice but only after staff refused to work as they felt they were not able to properly care for her medical needs.