June 28, 2013

The Honourable Vic Toews

Minister of Public Safety

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 40 th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Howard Sapers

Correctional Investigator

It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but its lowest ones.

- Nelson Mandela

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigator's Message

Special Focus on Diversity in Corrections

Case Study of Diversity in Corrections

III. Conditions of Confinement

Transparency and Accountability in Corrections

Correctional Investigators Outlook for 2013-14

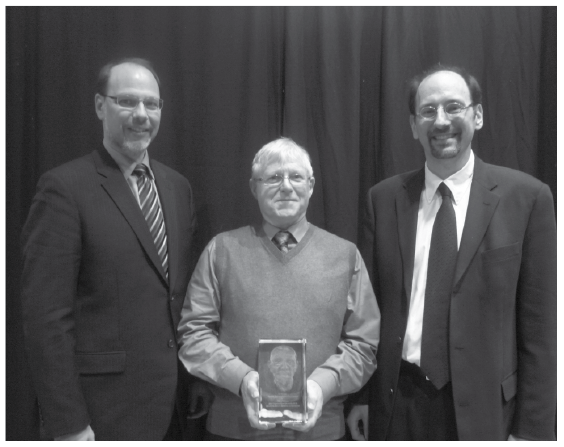

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Annex A: Summary of Recommendations

Correctional Investigator's Message

On June 1, 1973, then Solicitor General of Canada, the Honourable Warren Allmand, announced the appointment of the first Correctional Investigator for federally sentenced inmates. The Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI) was created in response to the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into Certain Disturbances at Kingston Penitentiary , which had identified the need for an independent body to review and provide redress to legitimate inmate grievances. The Commission summarized the conditions of confinement that prevailed at Kingston Penitentiary (KP) in April 1971 asrepressive and dehumanizing. Inmates had rioted and rampaged for four days, events which included six staff taken hostage, brutal violence, two inmate murders and the near total destruction of a section of the facility. As shocking as these events were, the KP riot was not isolated, but part of an escalating series of violent institutional disturbances in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Importantly, the Commission of Inquiry reported on the recourse to violence as a means of redressing long-standing grievances and of calling those grievances to the attention of the public. It found that the Canadian Penitentiary Service (as the Correctional Service of Canada was known at the time) lacked a transparent and impartial outlet for inmate complaint: there was no effective system to air or redress legitimate grievances; no recourse to review the actions or decisions of institutional authorities; no mechanism to bring public attention to prison conditions; and treatment was callous, abusive or degrading. Though 40 years removed from the circumstances that gave rise to one of the most infamous prison riots in the history of Canadian corrections, the Commissions assessment of its causes remains remarkably relevant and prescient:

We have already noted a number of causes for Kingstons failure: the aged facilities, overcrowding, the shortage of professional staff, a program that had been substantially curtailed, the confinement in the institution of a number of people who did not require maximum security confinement, too much time spent in cells, a lack of adequate channels to deal with complaints and the lack of an adequate staff which resulted in the breakdown of established procedures to deal with inmate requests. These facts were established beyond doubt by the testimony heard by the Commission. 1

As the Commission saw it, the system fundamentally failed because there was inadequate focus on the rehabilitative (orcorrectional) purpose to imprisonment. Today, as my report makes clear, many of the same problems that were endemic to prison life in the early 1970s crowding; too much time spent in cells; the curtailment of movement, association and contact with the outside world; lack of program capacity; the paucity of meaningful prison work or vocational skills training; and the polarization between inmates and custodial staff continue to be features of contemporary correctional practice.

Population management pressures inside federal penitentiaries continue to mount. More than 20% of the inmate population is double-bunked, confined to cells originally designed for one. As penitentiaries become more crowded, they also become more dangerous and unpredictable places for both staff and offenders. Inmate assaults with injuries and the rate of violent institutional incidents increased again last year. Inmate complaints and institutional charges remain high, as do the number of segregation placements and use of force interventions where a mental health concern is identified. This environment is particularly difficult on the growing complex needs populations in corrections federally sentenced women, mentally ill, Aboriginal, visible minority and aging offenders.

Reflecting these internal realities, the rate at which offenders are granted parole continues to set new historic lows. The trend lines are clear a greater percentage of offenders are spending longer and more of their sentence behind bars in increasingly volatile and hardening conditions of confinement. At a time when more offenders are remaining longer in custody, a renewed focus on CSC s rehabilitation obligations and a stronger commitment to community reintegration are as urgently required today as they were four decades ago. The 40 th Anniversary of the creation of the Office of the Correctional Investigator reminds us that Canadian correctional history is marked by a pattern of crisis and retrenchment followed by reform and progress. As the 1971 Commission of Inquiry found, the prison operating environment had masked unfairness, inequity and even brutality from public view. In a democratic society, outside intervention by independent oversight, the courts, Commissions of Inquiry and Parliament have been necessary to build a safer, more humane and effective correctional system. As an independent Ombudsman, our focus on fair and reasonable decision making, viewed through a human rights lens, keeps accountability at the forefront of federal corrections.

There are very sound reasons why the rule of law follows an offender into prison and why legality does not end at the prison gate. Even while deprived of liberty, the Supreme Court of Canada has affirmed that an incarcerated person is still a Canadian citizen, still a bearer of Charter rights and freedoms. The Corrections and Conditional Release Act ( CCRA ) puts it this way:offenders retain the rights of all members of society except those that are, as a consequence of the sentence, lawfully and necessarily removed or restricted. Imprisonment does not mean total deprivation or absolute forfeiture of rights. By law, prisoners maintain the right to be treated with dignity and respect, they have the right to safety and security of the person, to be treated humanely, to not be discriminated against on the basis of ethnicity or religion and to be free from degrading, cruel and/or inhumane treatment or punishment.

Legal compliance, however important, is not the sole test of CSC s conduct. CSC staff makes thousands of discretionary decisions each year. Good decision making is about more than legal compliance. Complying with the law is the floor, not the ceiling, for setting the standard in regard to administrative fairness. Good and best practices are about more than just doing the minimum.

Canadians expect their correctional authority to both uphold and model the principles and values of a free and democratic society transparency, accountability, equality, respect for human rights and fairness. It is not without purpose that I continue to call on the Correctional Service to respond publicly (and therefore openly and transparently) to my concerns and recommendations. This means more than simply meeting government reporting requirements. It means being proactive to make sure quality information is readily available and reasons for decision are clearly and fully stated. What happens behind prison walls is a reflection of the health and vitality of Canadian society. In my view, the matters that are brought forward in my Annual Reports use of force, treatment of mentally ill persons in prison, deaths in custody, prison crowding and violence, access to rehabilitative programs are of significant public interest and concern. Most offenders will eventually return to their home communities upon release. Conditions of confinement should support their preparation for community reintegration. After all, the point of prison is not to make model inmates, but to aid them to become better citizens.

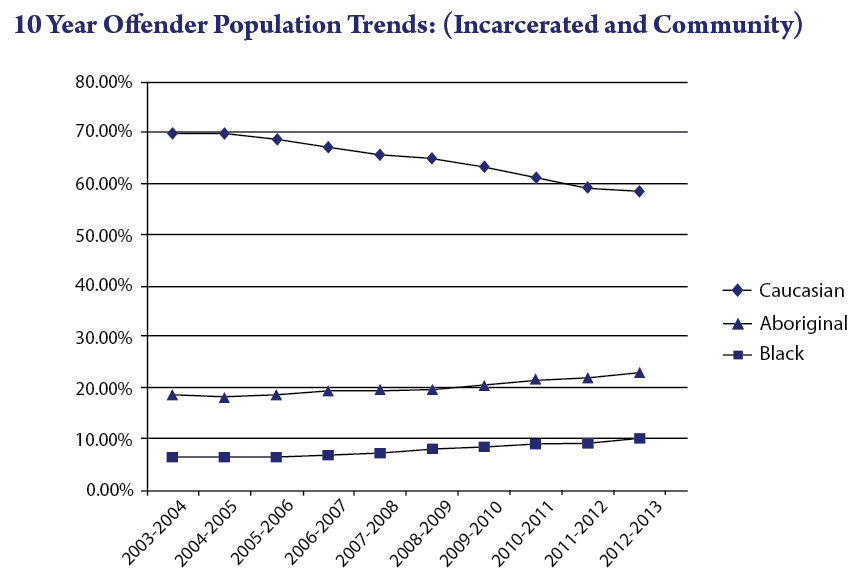

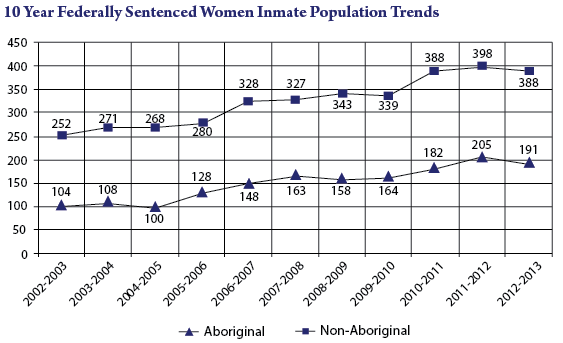

In this years Annual Report, I call special attention to the increasing diversity and complexity of prison demographics. In the 10 year period between March 2003 and March 2013, the incarcerated population has grown by close to 2,100 inmates, which represents an overall increase of 16.5%. During this period, the Aboriginal incarcerated population increased overall by 46.4%. Federally sentenced Aboriginal women inmates have increased by over 80% in the last 10 years. Visible minority groups (Black, Hispanic, Asian, East Indian and other ethnicities) behind bars increased by almost 75% over this period. As a subgroup, Black inmates have increased every year, growing by nearly 90% over the last 10 years. Meantime, Caucasian inmates actually declined by 3% over this same period.

When combined, the number of Aboriginal and visible minority inmates now exceeds 6,000 of a total incarcerated population of approximately 15,000. In other words, 40% of the 40% of the inmate count on any given day now comes from a non-Caucasian background. Recent inmate population growth is almost exclusively driven by absolute and relative increases in the composition of ethnically and culturally diverse offenders.

A more complex and diverse offender population profile mirrors larger demographic trends and patterns in Canadian society. As Statistics Canada reports, one trend consists of a younger, pluralistic and multicultural population whose diversity has been shaped over time by newer immigrants and foreign-born Canadians. Another trend reflects the increasing number of Canadians from Aboriginal heritage, while a third pattern reflects an aging, largely Caucasian majority, which is declining in both relative and absolute terms. On quite another level, disproportionate rates of incarceration of some minority groups, including Black and Aboriginal Canadians, reflect gaps in our social fabric and raise concerns about social inclusion, participation and equality of opportunity. Emerging demographic trends and patterns will shape and define who occupies federal penitentiaries for generations to come.

During the reporting period, CSC s contribution to the governments overall fiscal agenda has had an impact on a number of service delivery and program areas, including Inmate Welfare, Employment and Correctional Programming. Cost-saving and revenue-generating measures announced in FY 2012-13 will mean charging more for inmate telephone calls, an increase in room and board deductions, elimination of incentive pay for work in prison industries, cancellation of inmate social events (which help bridge the gap between prison and the outside world) and the closing of or reduced access to some inmate libraries.

The decision to not renew part-time prison chaplain contracts, primarily affecting non-Christian inmates, was particularly controversial, running contrary to the rising proportion of offenders from different cultures, nationalities, beliefs and religious affiliation in CSC facilities. Similarly, the end of funding for Lifeline , a program that provided inreach and outreach services and support to life sentenced offenders, appears unwarranted and contrary to long-established practice. Considered together, these measures reflect a narrowing of the rehabilitative potential of corrections.

Howard Sapers

Correctional Investigator of Canada

June 30, 2012

Executive Director's Message

The tempo and volume of work continues to remain high for the Office of the Correctional Investigator. From April 1, 2012, to March 31, 2013, the Offices team of 32 staff members (which includes corporate, policy, executive and investigative streams) spent more than 330 cumulative days visiting federal facilities, interviewed 1,309 offenders in institutions, responded to more than 5,400 offender complaints and answered 18,259 toll-free telephone calls. In addition, the Offices use of force team reviewed more than 1,400 uses of force incidents in CSC facilities.

The number of calls received or files opened are not the only, or even the best, measures of workload. The complexity of issues addressed and the compound nature of many complaints must also be considered. Moreover, the Office continues to identify, invest and address systemic issues of concern in an attempt to reduce the overall number of individual offender complaints.

During the reporting period, the Office continued to focus on system-wide concerns: a case study examining the treatment of chronic self-injurious women offenders; a review of practices at a maximum security penitentiary; and an investigation ofnatural cause deaths in federal custody. In addition, the summary results of a review of the Black inmate experience in federal corrections are featured in this years Annual Report, part of a larger thematic focus that the Office has undertaken on diversity in corrections.

For a small agency, investigations of this nature are intense and demanding, involve significant reassignment of personnel, sharing of workload and juggling of priorities while maintaining focus on the Offices core mandate to respond to individual offender complaints. The Office remains committed to investing in thematic reports and case studies that bring matters of substantive concern to the attention of CSC , the Minister of Public Safety, Parliamentarians and Canadians.

In terms of other accomplishments in 2012-13, the Office launched its revamped website (which last year recorded nearly 2 million visitorhits), developed a new Mission Statement and implemented a new Code of Conduct inspired by the values and principles of its role and mandate independence, accessibility, confidentiality and fairness.

Ivan Zinger, J.D., PhD

Executive Director and General Counsel

A Special Focus on Diversity in Corrections

The face of Canadian corrections is changing, mirroring an increasingly diverse, multi-ethnic and pluralistic society. The visible minority 2 offender population (community and incarcerated) has increased over the past 5 years by 40%. Visible minorities now constitute 18% of the total federally sentenced offender population (those incarcerated and in the community), which is largely consistent with representation rates in Canadian society. In 2011-12, Caucasians continued to make up the largest proportion of the federal offender population (62.3%). By comparison, Aboriginals represented 19.3%, Blacks 8.6%, Asians 3 5.4%, Hispanics 4 0.9% and other visible minority groups 3.4% of the population respectively. 5

Focusing on the last five years, the total offender population (community and incarcerated) increased by 1,539 offenders or 7.1%. All new net growth in the offender population can be accounted for by increases in Aboriginal (+793), Black (+585), Asian (+337) and other visible minority groups. By contrast, during the same time period, the total Caucasian offender population decreased (- 466 or 3%).

Diversity Within Diversity

While the tendency is to group all visible minority offenders together into one category, they are in fact a very diverse population. Nearly one-in-four visible minority inmates are foreign-born, coming from countries from all over the world, many of which have very different cultures, traditions and customs. Facilitating institutional adjustment and community reintegration for these offenders poses considerable challenges.

The Corrections and Conditional Release Act ( CCRA ) provides that correctional policies, programs and practices respect, among other things, ethnic, cultural and linguistic differences. CSC faces increasing pressure to accommodate a wide range of needs with respect to language, culture, religious identification, diet and ethnicity. Religious diversity within correctional facilities reflects what is now seen within the Canadian population. While the majority of inmates affiliate with Christianity, several other religious faiths are represented, for example Muslim (6%), Native Spirituality (6%), Buddhist (2%) and Sikh (1%). Different religious diets, clothing, medicines, books and worship practices adhered to by the faithful must be accommodated by the CSC .

Approximately 6% of the inmate population reports that the language spoken in their home is other than English or French. 6 The CSC is required to provide interpreters for offenders who do not speak Canadas two official languages for any formal hearing or for the purpose of understanding materials provided to the offender. While this ensures that inmates will be accommodated in formal proceedings, it does not address the challenges they have in day-to-day communications with correctional staff or for completing correctional programs.

Correctional Outcomes

Taken as a whole, visible minority inmates appear to have better correctional outcomes than the total offender population. Over the last 7 years, on average, less than 5% of visible minority inmates have been readmitted within two years of their warrant expiry date. However, grouping visible minorities together masks important differences in these very distinct groups. For example, the case study of the experience of Black inmates under federal custody demonstrates that correctional outcomes are not as encouraging for this visible minority group when compared to others.

When looking at diversity in corrections, it is important to understand what is happening in both relative and absolute terms. For example, the total number of institutional charges decreased by 5,731 in the last 4 years, which can be entirely attributable to the decrease in the number of charges against Caucasian inmates (- 6463). Meantime, institutional charges involving visible minority (+510) and Aboriginal (+222) inmates increased over the same period, even after accounting for increases in these populations. Black inmates are over-represented in use of force incidents, and, overall, visible minority inmates are over-represented in segregation placements.

A Case Study of Diversity in Corrections: The Black Inmate Experience in Federal Penitentiaries

In the 2011-12 Annual Report, the Office committed to a review of the experiences and outcomes of Black inmates in federal custody. A case study was completed over a 4-month period (November 2012 February 2013) which included a literature review, data analysis and qualitative interviews with Black Inmate Committees, Black inmates, CSC personnel, Audmax (an organization currently on contract with CSC to provide ethno-cultural services in the Ontario region) and community volunteers. Site visits were also conducted in institutions in the Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic region, recognizing that the majority of federally sentenced Black inmates (86%) are incarcerated in these regions.

The Chair of the Black Inmate Committee at each institution was contacted informing them of the case study and requesting their participation and assistance in consulting with members of the Committee to identify issues to bring forward as part of the case study. Notices were also posted on all ranges informing all Black inmates of the study and the opportunity to voluntarily participate. The Chair of the Black Inmate Committee was interviewed at each institution. Voluntary interviews were also conducted with interested Black inmates in one of three ways: individually, in small groups (2-3 participants) or in larger focus groups (15-20 participants). In total, 73 Black inmates (30 women and 43 men), were interviewed. Interviews were also conducted with 24 CSC personnel representing a variety of positions (e.g. Wardens, Correctional Officers, Program Managers), 2 community volunteers and Audmax. In addition, the OCI contracted with the Afrikan Canadian Prisoner Advocacy Coalition ( ACPAC ) to provide a literature review, expertise and analysis of Black Canadians in conflict with the law 7 .

| Institution | Region | Security level | # of Black inmates in 2011/12 | Black inmates as a proportion of the overall institutional population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joyceville | Ontario | Medium | 137 | 37% |

| Collins Bay | Ontario | Medium | 109 | 27% |

| Grand Valley Institution for Women | Ontario | Multi-level | 43 | 23% |

| Archambault | Quebec | Medium | 35 | 10% |

| Dorchester | Atlantic | Medium | 30 | 8% |

Findings

Black inmates are one of the fastest growing sub-populations in federal corrections. Over the last 10 years, the number of federally incarcerated Black inmates has increased by 80% from 778 to 1,403. Black inmates now account for 9.5% of the total prison population (up from 6.3% in 2003/04) while representing just 2.9% of the general Canadian population. 8

Population Management and Conditions of Confinement

Black inmates are disproportionately incarcerated in specific institutions in the Ontario and Quebec regions. While there are five medium security facilities in Ontario, nearly 60% of Black inmates are incarcerated in just two of those institutions (Joyceville and Collins Bay). Likewise, in Quebec, there are five medium security institutions, two of which house 60% of all Black inmates in the province (Cowansville and Archambault). This practice persists despite CSC s Population Management Strategy , which supports the integration of various populations in support of maintaining diverse institutions. CSC staff reported that ethno-cultural diversity reduces violence and contributes to an environment that is less prone to discrimination and cultural stereotyping.

Issues in Focus

While many Black inmates reported interactions with other inmates and staff that were considerate and respectful, nearly all Black inmates interviewed for the case study reported experiencing discrimination by correctional officials. The use of racist language, while present in all institutions, was not reported to be pervasive by those interviewed. More concerning to Black inmates was some of the behaviours exhibited by many staff members. As the literature indicates, the ways in which discrimination and prejudice are displayed or expressed have changed over time from more overt forms (e.g. racist language and behaviour) to more covert and subtle forms (e.g. ignoring, shunning) often making it difficult to recognize and counteract. 9 Much of what inmates reported to the Office falls within what the literature describes as covert discrimination.

For example, many talked about being ignored when asking questions: one inmate commented that correctional officerslook right through me and say nothing. They just look right through me like I am not standing right in front of them. Their needs did not appear to be a priority; their concerns were often ignored and many felt as though there were adifferent set of rules for Black inmates. While feelings of being ignored or disregarded by correctional staff are no doubt common to many inmates, this behaviour particularly resonates with Black inmates, as it reinforces their lived experiences with racism and discrimination on a daily basis. In prison, it increases feelings of marginalization, exclusion and isolation.

Numerous examples of stereotyping were also reported by Black inmates, primarily in terms of being characterized as agang member,trouble-maker,drug dealer orwomanizer. The gang member label was particularly troubling and deemed to be pervasively applied to Black male inmates. They felt as though everything they did or said was viewed through agang lens. Body language, manner of speaking, use of expressions, style of dress and association with others were often perceived as gang behaviour by CSC staff. Many CSC personnel agreed that stereotypes were regularly employed by some staff, viewing everything Black inmates did through bias and prejudice. This label impacts decision making in regard to security classification, program enrollment, work assignment and conditional release recommendation.

Black inmates reported feeling targeted with respect to institutional charges, particularly those that were more discretionary or requiring judgment on the part of correctional officers. The expressive nature of many Black inmates was often viewed by correctional staff as aggressive or disrespectful, while Black inmates felt as though it wasjust part of our culture. In 2011/12, Black inmates were over-represented in many of the categories of charges that could be considered discretionary. For example, Black inmates were disproportionately charged for disrespect toward staff (13%), disobeying an order (20%), and jeopardizing the safety/security of the institution or another person (23%). On the other hand, Black inmates tend to be under-represented in categories that required proof of an infraction, for example possession of stolen property (5%) or unauthorized items (8%).

A review of data over the previous five years reveals that Black inmates are consistently over-represented in administrative segregation, particularly involuntary and disciplinary placements. In 2012-13, Black inmates were disproportionately involved in use of force incidents.

Gang Affiliation

While Black inmates are twice as likely as compared to the overall population to have a gang affiliation, the majority (80.7%) are not a member of a gang. Despite this, the gang affiliation label is the one issue that seems to both distinguish and define the Black inmate experience in federal penitentiaries. Prejudice and bias have been well documented in other studies and inquiries of the Canadian criminal justice system. 10 Canadian research suggests that racial profiling exists where Black people are much more likely to experience police stop and search procedures. 11 Being subject to greater police surveillance has not only resulted in a greater likelihood of being caught when the law is broken but it alsoserves to further alienate Black people from mainstream Canadian society and reinforces perceptions of discrimination and racial injustice. 12 It is little surprise that this community experience follows Black Canadians into prisons.

On the surface, gang affiliation as identified, assessed and defined by CSC appears to be based on objective criteria: reliable source identification (informants, community or institutional sources); tangible written or electronic evidence (e.g. pictures); common and/or symbolic identification (e.g. scars, marks and tattoos or criminal organization paraphernalia); and observed behaviour that by its nature or association gives reasonable and probable grounds to believe that the offender has a gang affiliation. 13 In practice, these criteria are discretionary and prone to confirmation bias, the tendency to interpret information or behaviour in a way that confirms preconceptions and subjective judgments. Once applied, the validity and reliability of the gang label appear to be rarely questioned, particularly among those in operational positions working with Black inmates. This kind of labelling is particularly questionable when it relies on internal security intelligence information or prison informants, which are not always corroborated by external law enforcement, court or judicial authorities.

Programming

Despite being rated as a population having a lower risk to re-offend and lower need overall, 14 Black inmates are 1.5 times more likely to be placed in maximum security institutions where programming, employment, education, rehabilitative and social activities are limited. They are also less likely to have their Custody Rating Scale score overridden in favour of a placement in a medium or even minimum security institution.

Issues in Focus

Employment

Black inmates consistently reported difficulties finding employment, especially jobs oftrust or in positions which provide training in a particular trade (e.g. manufacturing, construction). The official prison unemployment rate in 2012-13 was 1.5%; however, for Black inmates this rate was 7%. Black inmates were also considerably less likely to be employed in a CORCAN industry 32% of inmates worked in a CORCAN enterprise compared to only 25% of Black inmates. 15 For those employed, Black inmates are essentially on par with the general inmate population with respect to inmate pay levels.

Grievances

In 2011-12, the top three categories for all inmate grievances were conditions of confinement/institutional routine (27%), interaction (24%) and health care (10%). Black inmates were most likely to file a grievance related to interaction (29%), conditions of confinement/institutional routine (22%) and visits/leisure (13%), highlighting that the quality of staff-offender relations is a particular concern for Black inmates. When the sub-categories ofinteraction are examined more closely, it is clear that Black inmates are over-represented in filing grievances for reasons of discrimination. Black inmates accounted for 25% of all inmate discrimination grievances. Black inmates were also over-represented in staff performance grievances.

Cultural Programming and Services

While Black offenders felt that CSC programs provided them with important tools and strategies, they did not feel that they adequately reflected their cultural reality. Black inmates reported that they could not see themselves reflected in program materials and activities and they felt these were not rooted in their cultural or historical experiences. Moreover, many initiatives and services which serve as important complements to CSC programming also fell short of expectations. Our review revealed:

- Inconsistent support for cultural events at the institutional level. Some Black Inmate Committees had sufficient guidance in planning events while others reported little to no assistance, to the point that very few events had ever taken place within the institution.

- A lack of community support. Many Black inmates had never seen, spoken with or met anyone from a Black community group while incarcerated, though most expressed a strong desire to develop and maintain these community linkages. (Importantly, this form of support is a key component of CSC s Strategic Plan for Aboriginal Corrections .)

- A need for better access to and availability of hygiene products specifically designed for their hair/skin type and cultural food items through the canteen.

- Lower grant rates for temporary absences, day and full parole. Programs that offer gradual, supervised release have been shown to reduce re-offending.

Concerns of Federally Sentenced Black Women

In 2011-12, there were 55 Black women inmates serving time in a federal penitentiary, representing 9.12% of the incarcerated women population. Over the past 10 years, the number of incarcerated Black women fluctuated very little between 2002 and 2010, at which point the number increased by 54% and then again by another 28% between 2010 and 2012. The number of incarcerated Black women appears to be rising quickly.

The majority of Black women inmates (78%) are held at Grand Valley Institution ( GVI ) in the Ontario region. Black women were most likely to be incarcerated for Schedule II (drug) offences 16 (53%). Interviews with Black women at GVI revealed that most were incarcerated for drug trafficking. Many indicated that they carried drugs across international borders primarily as an attempt to rise above poverty. There were some who reported/ indicated being forced into these activities with threats of violence to their children and/or families.

Most Black women interviewed were foreign nationals. Many indicated that the high cost of calling home from prison meant that they rarely spoke with family members. CSC policy does not allow for the use of considerably less expensive calling cards. (The Office will be more fully examining inmate telephone cost over the coming year). Restricted contact with home and family presents huge reintegration challenges, particularly because many face deportation upon completion of their sentence.

There were other concerns noted by the women in group and individual interviews: the lack of availability and access to special medicated creams and ointments for skin and hair care; lack of appropriate skills training (rather than laundering, folding, ironing and sewing of clothes); and, cuts to part-time chaplains, reflecting a concern that their spiritual needs could not be met by Christian chaplains. Finally, though many Black women at GVI were incarcerated for drug trafficking, conviction for this type of offence does not necessarily translate into having a drug addiction or substance abuse problem. Several women could not understand why they were required to complete these programs in the absence of an identified need.

Correctional Outcomes

As a group, Black inmates fare relatively well once released from prison. Over the last five years (2007/08 2011/12), successful completion rates for both federal day and full parole and statutory release supervision were consistently higher for Black offenders. Moreover, over the long term (for sentences completed between 1996/97 to 2000/01), of offenders who completed their sentences on full parole, statutory release or at warrant expiry, Black offenders were generally less likely to be readmitted on a new federal sentence. 17

Conclusion: What Does Diversity Mean for CSC ?

The Offices review of diversity in corrections and the case study of the experience of Black inmates in federal custody finds that, to its credit, CSC has implemented a number of measures to better identify and meet the needs of a more ethno-culturally diverse inmate population and it has implemented an organizational structure to support this work: diversity committees (e.g. national and regional ethno-cultural advisory committees, National Advisory Council on Diversity, National Diversity Committee); cultural programs and awareness activities; sensitivity and diversity training; and staffing initiatives aimed at increasing the representation of employment equity groups (e.g. targeted recruitment, Diversity and Employment Equity Committee, mentorship and leadership programs).

However, challenges remain to reflect, respond to and accommodate diversity. CSC must first ensure that its diversity training, recruitment efforts and retention policies and practices are consistent across all regions, integrated within the overall training framework and followed-up with ongoing practical training, experiences and support. A national diversity awareness training plan that begins at employee orientation and is continuous throughout a staff members career would enhance cultural awareness and cultural competency within CSC ranks. This training should be rooted in practical operational experience and target front-line correctional officers as a matter of priority.

While CSC meets and often exceeds workforce employment equity targets on a national basis, this is not well reflected at the institutional level. Not surprisingly, Black inmates cited more positive inmate-staff relations in one institution where the proportion of visible minority staff more closely reflected their numbers. Recruitment and retention strategies need to prioritize and target front-line institutions (not just Regional or National Headquarters) which house the greatest proportion of ethno-cultural offenders. Correctional officers who can speak languages other than English or French are increasingly important assets in improving interactions and communication with the rising number of foreign-born inmates.

The Offices review of diversity in corrections also yields some important findings with respect to the content, delivery and relevance of correctional programming. For example, ethno-cultural programs are often available in only one institution per region. This program delivery practice gives rise to population management strategies that run contrary to integrative practices and principles. It is also clear that core correctional programs need to be reviewed, revised and updated from a diversity perspective to incorporate more modules, examples and components drawn from lived ethno-cultural experience. More visible minority program facilitators would help ensure relevance, uptake and retention, potentially resulting in higher program completion rates.

Finally, as the results of the 2012 Ethical Climate Survey clearly demonstrate, there is much room for improvement in how CSC staff value and model respect, fairness, inclusiveness, accountability and professionalism in the workplace. 18 The voluntary staff survey collected information on abuse of power, discrimination, harassment, inappropriate behaviour and other rude and degrading treatment. Overall, close to 25% of respondents indicated that they had experienced discrimination on at least one of the prohibited grounds (race = 45%, gender = 43.6% and age = 36.3%) over the past year. Of those having experienced discrimination, over 60% reported that the source of discrimination was other co-workers senior to them in the department, including managers. 19 Of the sample reported, 31.8% have been harassed in the workplace in the past year, mostly by others senior to them, immediate supervisor(s) or colleagues in their own work unit. These results contribute to what was labelled in the survey as an unhealthy, eventoxic workplace. On the basis of how poorly CSC staff report they treat one another, it is an important question as to how offenders of different cultures, nationality, religion, creed or race are treated behind penitentiary walls.

The Offices review and case study of diversity in federal corrections suggests a number of areas for improvement. In terms of the way forward on these matters, I make two substantive recommendations:

1. I recommend that CSC develop a National Diversity Awareness Training Plan that provides practical and operational training in the areas of diversity, sensitivity awareness and cultural competency. This Training Plan should be integrated within the overall training framework.

2. I recommend that CSC establish an Ethnicity Liaison Officer position at each institution responsible for building and maintaining linkages with culturally diverse community groups and organizations, ensuring the needs of visible minority inmates are met and facilitating culturally appropriate program development and delivery at the site level.

I. Access to Health Care

Issues in Focus

Canadas correctional authority continues to face increasing costs and challenges in managing a higher proportion of the offender population with mental health concerns. The most recent data available indicates that the Correctional Service delivered at least one institutional mental health service to 48.3% of the total inmate population, with 47% of Aboriginal offenders and 75% of women offenders receiving services in FY 2011-12. Just over 90% (or 4,065) of newly admitted offenders were comprehensively screened for potential mental health problems last year; nearly two-thirds were flagged for follow-up mental health interventions. The Service also delivered Fundamentals of Mental Health training to 2,438 staff in fiscal year 2011-12. 20

Since 2005, the Service has invested approximately $90M in new funds to strengthen primary institutional mental health care service delivery, implement mental health screening at admission, train front-line staff in mental health awareness and enhance community partnerships and discharge planning for offenders with mental health disorders. These initiatives are part of CSC s five-point mental health strategy.

Health care remains the number one category of offender complaint to the Office. Staff visits to CSC facilities across the country confirm that access to health care, particularly mental health services and acute or complex care, remains fragmented and variable, especially in more remote penitentiaries.

As I have reported previously, in terms of inmate access to health care that meets professional and community standards of care, the CSC faces important staffing, recruitment and retention challenges. The Service employs a total of approximately 1,200 health care professionals, including nurses, psychologists, pharmacists, medical doctors and social workers. For FY 2011-12, the national vacancy rate for all health care positions in CSC was just over 8.5%. The psychologist vacancy rate in 2011-12 was 16% or 51 positions. The psychologist vacancy rate was highest for the Ontario region, at 29% or 23 positions. Fifty of 329 psychologist positions (or 15%) were filled by incumbents who are non-licensed staff (orunder-fills) and cannot deliver the same level or range of services as licensed psychologists. In other words, nearly one-third of CSC s total psychologist staff complement is either vacant orunder-filled. 21 Complicating professional recruitment and retention efforts are concerns about scope of practice, inter-provincial licensing and accreditation issues, as well as issues related to pay, professional development, and terms and conditions of employment.

Intermediate Care

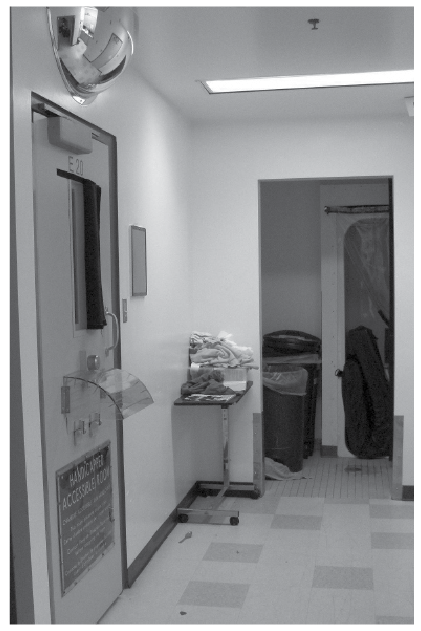

Nine years after launching its Mental Health Strategy in 2004, the intermediate care component for male offenders remains without a source of permanent funds 22 . The only male intermediate mental health care unit in the country, a pilot project at Kingston Penitentiary ( KP ) that began in November 2010, was to be terminated in March 2013. 23 Like elsewhere in the system, common problems plagued the pilot project:

- Aging and inappropriate infrastructure lacking in therapeutic design or purpose.

- Persistent staff turnover related to funding and recruitment challenges.

- Resort to filling professional health care positions with unregistered (orunder-fill) staff.

- Lack of 24-7 health care coverage (no dedicated clinical service delivery capacity to provide after-hours care or on the weekend).

- Lack of specialized mental health care training for new staff.

The cancellation of the intermediate care unit pilot is disappointing, but not entirely surprising given the context and challenges noted above. Unfortunately, it means that the majority of inmates requiring intermediate level interventions to manage their mental health needs will remain in general population or segregation in medium and maximum security facilities as a result of inadequate access to mental health care services and supports. They must rely on primary health care resources that are available in penitentiaries, unable to benefit from a more intensive level of services that intermediate care units could provide. These offenders do not have access to the services in the Regional Treatment Centres, as the admission criteria, rightfully so, screens them out.

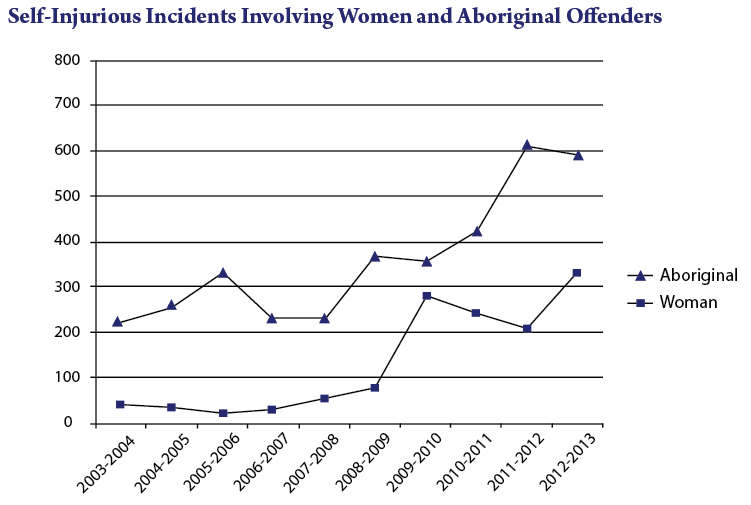

Management of Chronic Self-Injurious Offenders

I reported last year that the number of self-injury incidents in federal prisons has more than tripled in the last five years. The number of Aboriginal inmates engaging in self-injurious behaviour is a particularly troubling dimension of this problem. Self-injurious offenders are often managed in maximum security segregation units or observation cells, where conditions of confinement, lack of external stimuli and limited association can result in further deterioration in mental health functioning, leading to an escalation in the frequency and seriousness of self-injury. In some cases, the resort to self-destructive behaviour provides a form of coping and relief from the monotony, negative emotions and deprivations associated with penitentiary life. The known protective/preventive factors for self-injury in prisons less time locked in a cell; employment; meaningful association with others; engaging in correctional programs; regular and quality contacts with family appear to conflict with security and incident-driven responses that, in chronic cases, are reduced to simply keeping an offender alive.

The Office has documented a series of concerns with respect to the Correctional Services capacity and response to mental health service delivery:

- Over-reliance on use of force and control measures, such as physical restraints, and restrictions on movement and association to manage self-injurious offenders.

- Non-compliance with voluntary and informed consent to treatment protocols.

- Limited access to specialized acute services for federally sentenced women offenders.

- Inadequate physical infrastructure, staff, resources and capacity to meet complex mental health needs.

- Inappropriate monitoring and inadequate oversight in the use of physical restraints.

In my view, the lack of progress and noted gaps above in capacity and access, infrastructure and service delivery warrants consideration of a patient advocate or quality care coordinator model for federal corrections. Such models are becoming the standard of community mental health care practice in Canada and internationally. The legal, ethical and operational issues at play in CSC s Regional Treatment Centres e.g. informed and voluntary consent, the right to refuse or withdraw from treatment, legal certification under mental health regulations, among others are complex. Though designated psychiatric facilities, CSC treatment centres are in facthybrid facilities bothhospitals andpenitentiaries. As a hospital, these centres are subject to provisions of the relevant provincial mental health legislation. As a penitentiary, they operate under federal statute.

Operationally, the interplay between these entities patient vs. inmate, security vs. treatment, hospital vs. penitentiary creates its own tensions and contradictions. Moreover, access and continuity of care can be an issue as offenders make their transition from prison to the community. A patient advocate capacity appears all the more urgent and required in light of the decision to cancel the 10-bed Complex Needs program for male inmates who chronically self-injure, a pilot project which had been running at the Regional Treatment Centre in the Pacific Region since November 2010.

3. I recommend that CSC appoint independent patient advocates or quality care coordinators to serve each of its five Regional Treatment Centres.

Alternative Mental Health Care Measures

In December 2012, the Commissioner and Minister of Public Safety were provided a summary of six cases of acutely mentally ill offenders who, in the Offices opinion, cannot be appropriately managed or cared for in a federal penitentiary. All six of these offenders were subject to interventions by this Office recommending their transfer to an external psychiatric treatment facility. On some level, each of the case summaries raises disturbing parallels to Ashley Smiths preventable death in October 2007. Like Ashley, these offenders have complex and acute mental health care needs well beyond the resources or capacity of the Service to safely or humanely manage.

The cases brought forward by the Office provide evidence that the sentence for these individuals needs to be medically managed and their serial and prolific self-injury warrants transfer to outside treatment facilities. Most have been involved in dozens of uses of force interventions to prevent or interrupt patterns of repetitive self-harming. Some are certified under provincial mental health legislation. Most have a protracted history of childhood physical, mental and sexual abuse. A few arelow functioning, more child-like in their responses and emotional development. One is disfigured and permanently brain injured from repetitive and chronic head-banging. All have an extensive history and diagnosis of mental illness. One is adual status offender following a previous finding of Not Criminally Responsible . Several have been the subject of reviews by National Boards of Investigation. These offenders can be disruptive, their behaviour causes significant staff stress and their care and management can be extremely expensive. Many have been managed on around the clock suicide watch, mostly in long-term segregation or observation cells largely devoid of stimuli.

As of the writing of this report, the Office has not yet received a full response to its December 2012 correspondence. CSC should and can provide mental health supports for the greater majority of federally sentenced offenders. But it should contract out services for the few that require highly specialized mental health care interventions and treatment. With respect to managing acute physical health conditions, the Service regularly moves offenders into community hospitals and external treatment centres. There is a corresponding and requisite need to do the same in managing acute mental health cases. Outside psychiatric hospitals provide a therapeutic environment where interventions are conducted by a team of health care professionals. This is not the case in federal penitentiaries, not even in the Regional Treatment Centres, where first responders are typically correctional officers who may or may not be accompanied by Health Services personnel. Segregation, pepper spray and restraints are not treatment for mentally ill individuals.

The management and treatment of mentally disordered individuals in correctional facilities is extremely challenging work. We should not expect the Correctional Service to do the impossible. The Office does not question the integrity, commitment or professionalism of CSC s efforts. However, we should not be relying on facilities that were never designed to accommodate or care for individuals with serious mental health issues and those who seriously and chronically self-injure. I am increasingly of the opinion that modest and incremental reform of a system that is fundamentally flawed is not in the public interest. Some mentally ill individuals in federal penitentiaries do not belong there and should be transferred to outside treatment facilities as a matter of priority.

4. I recommend that the CSC immediately identify the most severely mentally ill male and female inmates for review by external mental health experts and formulate health-focused treatment and placement options.

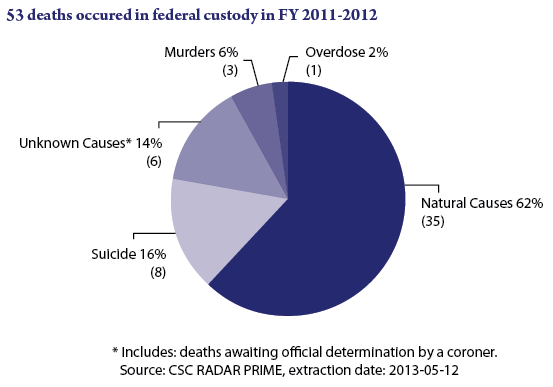

II. Deaths in Custody

In 2011-12 there were 53 deaths recorded in CSC facilities, including eight prison suicides and 35 deaths fromnatural causes. These numbers in part reflect the fact that more offenders are serving longer sentences, more are sentenced later in life and more are growing old and dying behind bars. As the inmate population ages, the number of deaths attributable tonatural causes far exceeds other types of death as the leading cause of death in federal custody.

Section 19 and Death in Custody Reviews

With respect to CCRA Section 19 review of deaths in custody, in FY 2012-13 the Office investigated a troubling case where next of kin notification procedures had gone very wrong. Based on this and other case reviews, the lack of information provided to families by CSC about the circumstances and causes of death of a loved one continues to be a matter of concern. There is little that isnatural about dying in a federal prison. Few terminally ill inmates receivecompassionate release to die with some semblance of dignity in the community. Meantime, the manner in which CSC chooses to inform the public of a death in one of its facilities suggests that there is more to be done to respect the dignity, privacy and confidentiality of all parties.

Of considerable concern is CSC s relatively new streamlined Mortality Review Process ( MRP ) for investigating so-called natural deaths in custody. The MRP is a shortcut that appears to be unequal to the requirements of Section 19. These matters are currently under investigation, the findings of which will be issued in the coming year.

National Forum for Preventing Deaths in Custody

Canada lacks an independent, high-level review mechanism to review and help prevent deaths in custody. There is no Ministerial-level panel or Parliamentary Committee that looks into the number or rate of deaths in federal prisons, provincial and territorial jails, or law enforcement or immigration detention facilities. 24 During the reporting period, the Offices review of the circumstances contributing to inmate deaths in federal custody suggests that these events continue to be responded to episodically rather than systematically. Despite a number of draft attempts, CSC still has no consolidated or publicly available performance and accountability strategy focused on the prevention and reduction of preventable or premature deaths in federal custody.

Coroner and Medical Examiner reviews, inquests and reports continue to demonstrate scope for further learning in terms of applying lessons in assessing and managing the risk of suicide, overdoses and other deaths in custody. However, these reviews have had little sustained impact in part because there is no official body to share, let alone enforce their findings or recommendations. As a matter of practice, some provincial jurisdictions do not automatically review or probe a death in federal custody when it wasexpected or attributable tonatural causes. Moreover, public fatality inquiries are often conducted long after the fact, raising serious concern about CSC s capacity to identify and correct systemic deficiencies in a timely and responsive manner.

5. I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety create an independent national advisory forum drawn from experts, practitioners and stakeholder groups to review trends, share lessons learned and suggest research that will reduce the number and rate of deaths in custody in Canada.

III. Conditions of Confinement

Population Management

In the three year period between March 2010 and March 2013, the federal in-custody population increased by 1,214 inmates or 8.4%. 25 When the numbers are broken down it is apparent that recent population growth is not evenly distributed across CSC s five regions. The Ontario and Prairie Regions lead population growth, both in proportionate and absolute terms. Both regions continue to exceed rated capacities and have resorted to some extraordinary measures to manage rising inmate numbers, including inter-regional and involuntary transfers, which raise significant legal rights, due process and fairness considerations.

The system is exhibiting strains in safely managing an increasing population through daily routines and providing adequate access to programs and services. At the national, regional and local levels, there are policies and procedures in place limiting the number of offenders that may be associating on a range, outside in the yard or in the cafeteria for meals at a given time. It becomes increasingly difficult to coordinate daily prison routines that are compliant with legal, policy and procedural guidelines as populations increase.

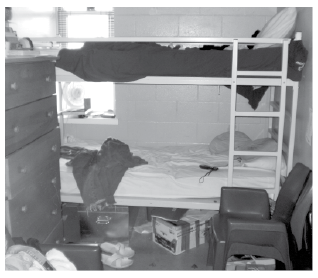

Double-Bunking

As of March 31, 2013, the national double bunking rate, the practice of confining two inmates in a cell designed for one, was 20.98%. The Office has long raised concerns with this practice. In January 2013, the Office received a paper forwarded by the local UCCO - SACC - CSN Executive at Bath Institution, a medium security facility in Ontario, outlining its concerns about double-bunking. The following excerpt summarizes the issues at stake:

(T)here is a correlation between double bunking and an increase in serious institutional incidents. The act of double bunking creates problems by multiplying the offender population within limited infrastructure. When large groups of inmates are forced to live together in minimal space (they) begin to fight over such things as washrooms, televisions, phones, food, recreational areas and equipment Therefore higher rates of aggression, violence, injury from other and self-injurious behaviours may increase due to the increased anxiety and demands on stressed individuals. Inmates generally deal with this type of anxiety by withdrawal from programming, vocational and recreational activities, as they deal with feelings of depression and or aggression, which greatly diminish a chance to succeed with their correctional plan. The institutional overcrowding and lack of institutional employment also leads to an increasing number of institutional security incidents. 26

Inmate views of double bunking are almost equally negative and pessimistic. Being locked up in a space about the size of an average bathroom with another person inevitably means diminished privacy and dignity, and increases the potential for tension and violence. Inmates describe the experience to the Office as demoralizing and degrading.

The Prairie Region exemplifies these pressures. Over the past five years, the number of incidents of assault (including assaults on other inmates, visitors, and staff; inmate fights; and sexual assaults) increased by 60% (from 366 in FY 2008-09 to 586 in FY 2011-12). The number of use of force incidents increased by 48% (from 265 to 393) over the same period. In the last three years, there have been five inmate murders in the Prairie Region, accounting for more than half of all inmate homicides in federal penitentiaries.

These violent events often translate into further disruptions to the prison routine resulting in a high number of lockdowns, searches, time spent in cells and staff refusals to work on occupational health or safety grounds. There were 428 lockdowns recorded in CSC facilities during FY 2012-2013. The response to these incidents negatively impacts on staff and offenders alike, and raises obvious personal safety and institutional security concerns. Other performance measures that speak to deteriorating conditions inside federal institutions disciplinary and institutional charges, use of force interventions, incidents of self-harm, number of minor and major disturbances, segregation placements, offender grievances suggest that many key indicators are trending in the wrong direction.

Issues in Focus

Issues in Focus

Inmate Accommodation Policy

In the reporting period, the Service finally promulgated its long-awaited revised policy standards on inmate accommodation. The new Commissioners Directive is seriously flawed and signifies a dramatic reversal in terms of principles and standards. Most significantly, the new policy direction removes two long-standing tenets of federal correctional practice:single occupancy accommodation is the most desirable and correctionally appropriate method of housing offenders anddouble bunking is inappropriate as a permanent accommodation measure within the context of corrections. These omissions normalize double-bunking as a response to population pressures rather than consider it an exceptional or temporary measure or as an option of last resort.

There are other problems with the revised policy. For example, the new policy continues to require correctional officers to complete the double-bunking assessment to ensure compatibility between cell mates. The Office has long considered this practice inadequate particularly given the amount of information and level of assessment required (psychological profile, medical information, criminal history, compatibility, predatory/permissive behaviour and vulnerability) to make informed judgments. In the Offices view, this type of assessment is more appropriately carried out with the oversight of the Warden and should be subject to periodic review by regional authorities.

A recent CSC audit noted that of the 216 double-bunked offenders files reviewed only 56% (or 120 of 216) had a double-bunking assessment on file for their current cellmate. 27 Even with new policy direction, front-line staff continue to report confusion regarding who is responsible for completing double-bunking assessments. These findings confirm the Offices experience that these assessments are often missing, incomplete or superficial.

The new policy standard also removes reference to limits on the maximum number of inmates that an institution is permitted to hold by security level. The size and scale of a correctional facility is extremely important. Large facilities (in excess of 300 offenders) tend to reinforce an environment of anonymity and may promote individual feelings of powerlessness, isolation and embitterment, sentiments which are counterproductive to correctional programming and reintegration purposes. The removal of upper limits runs contrary to long-standing evidence, which suggests that smaller scale institutions are safer, better managed and deliver superior correctional outcomes. 28

In response to these concerns, the Senior Deputy Commissioner stated in correspondence dated October 29, 2012, that the new inmate accommodation standardsmust not be interpreted as a change in direction as CSC recognizes that single occupancy accommodation is the most desirable and appropriate method of housing offenders. If this is indeed the case, it begs the question why seeminglydesirable andappropriate single cell occupancy standards and physical limits on the size of CSC institutions were removed from the accommodation policy framework in the first place. A recent CSC research report evaluating the effects of prison crowding concedes thatthe literature does suggest a relationship exists between crowding and psychological and physiological stress for offenders, and, furthermore, there is aneffect of crowding on institutional misconduct. The report concludes thatscholars and criminal justice organizations, including CSC , agree that double bunking should not become a common practice or a long-term strategy in correctional facilities. 29 CSC s revised inmate accommodation policy runs contrary to the available evidence and experience, which indicates that without proper safeguards double bunking as a response to prison crowding is a practice that jeopardizes staff and inmate safety.

6. I recommend that CSC s inmate accommodation policy reinstate the principle that single occupancy is the most desirable and correctionally appropriate method of housing offenders.

Issues in Focus

The Office has identified some serious gaps in CSC s use of force review process which once again calls into question the systems capacity to detect and correct deficiencies. As part of policy changes to the use of force review process that went into effect in April and June 2012, the number and types of incidents that are subject to a regional or national review have been significantly reduced. Under the new rules,moderate use of force incidents are now subject to regional (or level two) review in only 25% of cases. A national review involves aselective random sample of 5% of use of force incidents pulled from the regional review process. The Office is concerned that non-compliant or inappropriate uses of force are not making their way up the review and accountability chain as they should. There is still no clear national policy direction on how cases at the regional or headquarters levels are selected for the 25% and 5% reviews. Unless a use of force intervention isflagged at the regional level, it may never be brought to the attention of national authorities.

It is my view that it is inappropriate to leave review of use of force incidents to random selection. Experience and common sense dictate a need to both assure and ensure force is used appropriately, judiciously and proportionately in a correctional setting. Reliable mechanisms must be in place to record, review and report use of force incidents. Previously, national authorities reviewed all use of force events that occurred in CSC facilities across the country, but as a result of these new policy directives, they are nowrandomly reviewing just 5% of the over 1,200 reported incidents annually. Surely the point of having a use of force review process is to hold the organization to account by identifying areas of non-compliance and correcting deficiencies. It is simply not wise to dilute oversight or download accountability for this high-risk activity.

The Office has reported serious and long-standing compliance problems in meeting current use of force guidelines, including post-use of force health care assessments, videotaping and decontamination procedures. These deficiencies are of particular concern because close to 60% of all use of force scenarios involve the use of an inflammatory spray, 16% of incidents take place where a mental health concern is identified and nearly 10% did not meet the most reasonable, safest or least restrictive use of force option available. These already poor compliance rates would seem to require decidedly more attention and involvement by national authorities, not less.

7. I recommend that any use of force incident involving a mentally disordered offender be subject to a mandatory review at the institutional and regional levels. Issues of non-compliance should be submitted to National Headquarters for review and identification of corrective measures.

8. I recommend that regional authorities review all use of force incidents involving the use of Institutional Emergency Response Teams.

It is distressing to note that some front-line staff continue to insist that the drawing or display of a weapon (e.g. baton, pepper spray or even shotgun) should be reported differently from its actual use or discharging. In these matters, there is a long-standing discrepancy between incidents and reporting of what is deemedreportable (and therefore reviewable) and what is considered routine. The policy on these matters is perfectly clear: areportable use of force includes the use and/or the threat, display, loading or charging of a weapon, including the display of a pepper spray canister. 30 Among trained, certified and professional staff, there should be no room for ambiguity on these matters; similar regulations govern all law enforcement agencies in Canada. There are good legal and practical reasons why these procedures have been adopted and why they should be followed as a matter of both procedure and principle.

There are other troubling practices. Uses of force reviews systematically do not meet the review period timelines: it is not an uncommon occurrence for an offender to have been released, transferred or otherwise moved on with his/her life before the review of the incident is ever completed. There are some use of force packages that date back as far as 2009 that are still consideredpending by CSC . In too many cases, by the time that the file is finally reviewed or makes its way through the review levels, the actors have changed and there is simply no opportunity to take meaningful follow-up or corrective measures. For CSC , a case status ofpending often translates intono further action required.

This year, the Office reviewed a number of files subject to national level review that were little more thancut and paste reports involving minimal analytical effort and offering little in the way of value-added. The reviews were often superficial and perfunctory in both form and fashion. More significantly, the Office noted interference by National Headquarters in some of its requests to share information or files from regional authorities. Office notification of serious cases does not happen routinely in all regions or as a matter of policy, as it should. Cases that, in the Offices view, merit proceeding directly to a nationalpriority review can linger or languish interminably in procedural delays. That said, the Office is not a substitute (orfail-safe) for CSC s administrative use of force review process. It is the Services legal obligation to ensure use of force interventions comply with the letter of the law.

Emergency Response Teams

In use of force files reviewed by the Office in FY 2012-13, Emergency Response Teams ( ERT s) responded to over 10% of all use of force interventions in male facilities. While traditionally reserved for high-risk procedures (e.g. to quell disturbances or perform a cell extraction of a physically uncooperative inmate), ERT s are increasingly used in support roles such as escorts or internal population movements. In some institutions,shadowing of front-line staff by the ERT , to facilitate a range search for example, has become standard procedure. Fully outfitted in their protective gear, ERT s have even been used tosupervise medical treatment. Under the new use of force review procedures, there is no policy obligation to report deployments of ERT s.

Use of force scenarios where mental health concerns are identified are increasing. ERT s may also be called in to manage a mentally disordered offender who isacting out. Use of force interventions involvingproblematic or non-compliant inmates often involves situations where a mental health issue is the underlying basis of thebizarre orthreatening behaviour. In deployments involving mentally disordered offenders, the composition and comportment of a fully armed and equipped ERT does not normally allow for subtlety in purpose or action. The Office reviewed video evidence of some ERT actions that raise serious concern about the nature and appropriateness of the degree and level of force used in cases involving mentally disordered offenders. These are not isolated occurrences.

9. I recommend that Emergency Response Training be updated to include standards and protocols when responding to situations where a mental health concern is identified. Awareness training in mental health issues and self-injurious behaviour, including de-escalation techniques, should be mandatory components of this training.

Information and Privacy

The Privacy Act imposes certain obligations on federal departments and agencies with respect to the protection of personal information that it collects, stores, uses or disseminates. Given the amount and array of sensitive information that CSC collects and possesses, the Service is obligated to ensure there are practices and processes in place to safeguard against any potential privacy risk or unauthorized sharing of personal information.

On an annual basis, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada receives a substantial number of formal complaints accounting for approximately one-third of its overall complaint caseload from federally sentenced offenders. These complaints typically involve the inappropriate use, access or disclosure of personal information either held or collected by the CSC . In a prison setting, breaches of protected personal information, such as inmate medical records, security intelligence information or criminal history, can have serious consequences.

10. I recommend that the CSC conduct an internal audit of its practices and procedures to protect personal inmate information.

Issues in Focus

IV. Aboriginal Issues

To be clear, courts must take judicial notice of such matters as the history of colonialism, displacement, and residential schools and how that history continues to translate into lower educational attainment, lower incomes, higher unemployment, higher rates of substance abuse and suicide, and of course higher levels of incarceration for Aboriginal peoples. ( R. v. Ipeelee , SCC 13 2012)

The federal Aboriginal offender population is complex. As one of the youngest and fastest growing segments of Canadas population, Aboriginal people are likely to continue to experience disproportionate rates of incarceration. 31 The Aboriginal incarceration rate is already estimated to be 10 times higher than the national average. 32 Today, 22% of the total federal inmate population claims Aboriginal ancestry. Aboriginal women represent 33.6% of all federally sentenced women in Canada. Current sentencing trends combined with a growing and youthful demographic indicate that the over-representation of Aboriginal people in Canadas correctional system is likely to grow.

Some progress is being reported:

- Aboriginal offenders access their first Nationally Recognized Correctional Program ( NRCP ) faster than non-Aboriginal offenders.

- A greater percentage of Aboriginal offenders with an identified employment need receive vocation skills training or certification prior to Full Parole Eligibility Dates compared to non-Aboriginal offenders.

- Aboriginal offenders access their first community-based NRCP faster than non-Aboriginal offenders.

- The percentage of offenders with Educational referrals approved within 120 days of admission is greater for Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal offenders.

However, on many key indicators of correctional performance and outcome, the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal offenders continues to widen:

- Aboriginal offenders are kept behind bars for longer periods and at higher security levels than their non-Aboriginal counterparts.

- They are over-represented in segregation placements, maximum security populations, institutional charges and in use of force incidents.

- Although conditional release grant rates are low for all inmates, they are far worse and deteriorating faster for Aboriginal men and women; indeed, most Aboriginal inmates are released on statutory release (two-thirds point of the sentence) or warrant expiry, not parole.

- Aboriginal offenders accounted for 45% of all self-injury incidents in federal prisons last fiscal year. 33

Since 2005-06, the Aboriginal inmate population has increased by over 40%. There are now more than 3,500 Aboriginal people behind bars in federal penitentiaries. More than half of the daily inmate count at several institutions in the Prairie Region is Aboriginal.

The over-representation of Aboriginal men and women entangled in Canadas criminal justice system is not new. The social, cultural, historical and economic factors that give rise to incarceration rates that are 10 times higher for Aboriginal people have been extensively documented. In R. v. Gladue (1999) and R. v. Ipeelee (2012), the Supreme Court of Canada confirmed that the social history of an Aboriginal offender (also known as Gladue factors) is to be considered when the interests of an Aboriginal offender are at stake:

- Effects of the residential school system.

- Experience in the child welfare or adoption system.

- Effects of the dislocation and dispossession of Aboriginal people.

- Family or community history of suicide, substance abuse and/or victimization.

- Loss of, or struggle with, cultural/spiritual identity.

- Level or lack of formal education.

- Poverty and poor living conditions.

- Exposure to/membership in, Aboriginal street gangs.

Despite incorporation into CSC s policy framework, there is little evidence to suggest that Gladue principles are routinely applied by CSC authorities or making a tangible difference in the lives of Aboriginal people under federal sentence.

Spirit Matters

This was the context in which the Office released, on March 7, 2013, a systemic investigation into how CSC has responded to Parliaments direction to share care and custody of Aboriginal offenders with Aboriginal communities under Sections 81 and 84 of the CCRA . The report entitled, Spirit Matters: Aboriginal People and the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , 34 marked only the second time in the history of the Office that Section 193 provisions of the CCRA Special Report to Parliament have been used. In the Offices assessment, the issues facing Canadas Aboriginal people in the federal correctional system are both significant and urgent, and demanded a comprehensive and immediate response.

There were a series of unforeseen procedural delays leading up to the reports eventual tabling in Parliament. The final report was submitted to the Commissioner on October 22, 2012. As per standard Office practice, the Commissioner was asked to respond to the reports 10 recommendations by November 12, 2012. Despite a number of follow-up requests, by the end of December I still had not received the Commissioners response. On January 7, 2013, I asked the Minister to intervene. In response, on January 30, 2013, the Minister invited me to submit my report to him for the purpose of tabling in Parliament pursuant to Section 193 ( Special Report ) provisions of the CCRA . In light of the importance and urgency of the issues under consideration, and given that I still had not received CSC s response, I decided to have the report released through tabling under Section 193. Spirit Matters was finally tabled in Parliament on March 7, 2013, four months after it had been sent to the Commissioner for his response.

I expected a meaningful and comprehensive response, consistent with the extraordinary measures that were taken to have Spirit Matters laid before Parliament. In the end, the Correctional Services response was neither. In correspondence sent to the Commissioner on March 8, 2013, I stated that CSC s response lackedsubstance, meaning and clarity. On some matters, for example my recommendation to appoint a Deputy Commissioner for Aboriginal Corrections, the response simply recycled previously held CSC positions. My conclusion then, as it is now, is that CSC s response did not meet the urgency, immediacy or importance of the issues that my Special Report to Parliament warranted. My concerns about CSC s response were subsequently shared with the Minister.

11. I recommend that the Correctional Service of Canada publish a public accountability report card summarizing key correctional outcomes, programs and services for Aboriginal people, to be tabled annually in Parliament by the Minister of Public Safety.

12. I recommend that in the coming year, the Correctional Service of Canada publish an update to its response to Spirit Matters in collaboration and consultation with its National Aboriginal Advisory Committee.

13. I recommend that the Correctional Service of Canada audit the use of Gladue principles in correctional decision making affecting significant life and liberty interests of Aboriginal offenders, to include penitentiary placements, security classification, segregation, use of force, health care and conditional release.

V. Access to Programs

Prison Work and Vocational Skills Training

Approximately three in five offenders have employment needs at intake to a correctional facility. CSC research has confirmed a number of positive associations between offenders engaged in prison work and vocational skills training during incarceration:

- Lower rates of admission to segregation

- Fewer institutional charges

- Higher parole grant rates

- More likely to attain and hold a job in the community