June 29, 2018

The Honourable Ralph Goodale

Minister of Public Safety

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 45 th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigator's Message

1. Health Care in Federal Corrections

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

Special Focus: Investigation into the Riot at Saskatchewan Penitentiary

5. Safe and Timely Reintegration

Correctional Investigator's Outlook for 2018-19

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Annex A: Summary of Recommendations

Responses to the 45 th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator

CORRECTIONAL INVESTIGATOR'S MESSAGE

Photo of Dr. Ivan Zinger,

Correctional Investigator of Canada

The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.

- Attributed to Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1862)

As I start the first year of a five-year appointment, it is perhaps expected that I would provide some level of detail on the approach and direction I intend to take in my role as Correctional Investigator of Canada. It is my belief that transparency in corrections leads to greater accountability, better performance and improved public safety results. Under section 180 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , I am required to provide notice and report to the Minister whenever the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) does not, in my opinion, adequately respond to the findings and recommendations of my Office. As I read it, this section of the legislation is not optional.

As such, and in the spirit of openness and transparency, this past year I notified the Minister on three separate occasions on the inadequacy of CSC's responses to my recommendations:

- The Services response to Fatal Response: An Investigation into the Preventable Death of Matthew Ryan Hines , tabled as a Special Report to Parliament on May 2, 2017.

- The Services response to Missed Opportunities: The Experience of Young Adults Incarcerated in Federal Penitentiaries , released on October 3, 2017.

- The Services response to my 2016-17 Annual Report, released on October 31, 2017.

In all three instances, the Services initial response was deemed deficient. Though I did subsequently receive a second, more positive response to the Matthew Hines investigation and report, it appeared to have come only after interventions of the Minister's Office and Departmental officials. With respect to Missed Opportunities , CSC rejected the underlying finding that younger people in federal prisons should be treated differently. CSC's responsiveness to a number of other recommendations made in last years Annual Report remains a "work in progress".

Photo of an Institution entrance

It is especially concerning when the Service fails to respond to recommendations issued by my Office ( Missed Opportunities ) or dismisses the Office's initial findings (Saskatchewan Penitentiary riot). It is even more perplexing when CSC initiates its own consultation and review after the Office has already investigated and reported on the matter (Secure Units for women offenders). Not surprisingly, progress appears stalled, stuck or even regressive in some highly visible areas of correctional practice:

- Management of maximum security women at the Regional Women's Facilities.

- Indigenous corrections (influence of Aboriginal-based street gangs in prison; not enough community bed space, facilities and services operated by Indigenous communities for Indigenous offenders).

- Health care (clinical independence of health care providers; alternatives to incarceration for complex needs cases; models of care and support for elderly and aging, geriatric, palliative and terminally ill prisoners).

Needless to say, 2017-18 presented its share of challenges. I welcome and look forward to the opportunity to working with a newly appointed Commissioner of Corrections. Leadership renewal at the very top of the agency anticipates a change in perspective and direction. A new leader could be expected to restore focus and commitment on the essentials of what might be called a "back-to-basics" approach to corrections. In that light, it is important to recall that the term corrections derives from the Latin verb "corrigere" , which literally means "to make straight, bring into order". At its most basic level, the purpose of corrections is to "correct". Experience tells us that understanding human behaviour, much less correcting it, is a complex, challenging and uncertain endeavour.

At the organizational level, the ultimate goals of corrections are offender rehabilitation and safe, gradual and supervised return to the community. Correctional performance is most often measured by recidivism, or the rate of reoffending and readmission to prison on a new sentence. Research tells us that gradual and structured releases from minimum security facilities produce better public safety outcomes than releases from higher security or abrupt releases at later or end stage of the sentence. While I would like to report on current recidivism rates for federal corrections as a performance measure, there is currently no regularly maintained database tracking any new offence after warrant expiry. CSC tracks the proportion of offenders who are returned to custody on a new federal sentence. On this measure, offenders appear to be returning to federal custody less often (18% in 2001-02 versus 16% in 2011-12), though readmission remains elevated for Indigenous people at 23.4%. Although valuable and trending in the right direction, these indicators do not include provincial and territorial convictions (less than two years), which account for the vast majority of adult convictions.

In 2003, Public Safety Canada published a study looking at any new criminal convictions (including provincial and territorial records) resulting in a return to provincial or federal custody. It found that the two-year reconviction rate for federally sentenced offenders released in 1994-95, 1995-96, and 1996-97 was 42.5% overall 42.9% for men, 27.5% for women and 56% for Indigenous men. The current national base recidivism rate is simply not known. After decades of experience with research and performance measurement in the field of corrections and criminal justice, Canada still lacks a robust, regularly maintained, national recidivism database. Although it may seem unusual to make recommendations in my opening message, given the Government of Canadas commitment to track performance and effectiveness of its various departments, I offer the following:

Photo of a section of garden from the horticultural program

- I recommend that Public Safety Canada develop a nationally maintained recidivism database that links federal, provincial, and territorial jurisdictions. This database should publicly report on reoffending before and after warrant expiry dates (WED), for both violent and non-violent offences, and should include post-WED follow-up periods of at least two and five years.

For a new leader, it is also important to recall that the Correctional Service is a public service, one that is dedicated to providing support, assistance and services to federal offenders, their communities and Canadians. As part of the criminal justice system, the function of corrections is sentence administration. Ultimately, it is the courts that decide who is sent to prison and for how long. CSC's job is to decide how best to manage that sentence. Corrections is not law enforcement or policing. In a free and democratic society, the deprivation of liberty is the punishment. Offenders are sent to prison as punishment, not for punishment. In practice, offenders retain all rights, liberties and freedoms voting, religious practices, expression except those that are necessarily restricted as a consequence of the sentence. Corrections requires, but is not limited to safe and secure custody. The point is not to make model inmates; it is to mold better citizens by assisting those in conflict with the law to live a law-abiding life upon their return to the community.

Photo of an Infirmary cell

Corrections is an area of public policy shaped and influenced by government direction. The history of corrections in Canada tends to move between and through cycles of reform, retrenchment and regression. Until recently, a "tough on crime" agenda dominated criminal justice policy in Canada. The politics behind this message stressed longer and harsher mandatory penalties, more austere and punitive prison living conditions, fewer opportunities for criminal justice diversion and restricted access to parole for offenders. Policy direction was given for correctional and paroling authorities to administer and adjudicate a federal sentence based on "the nature and gravity of the offence" and "the degree of responsibility of the offender". The least restrictive principle gave way to a more elastic concept "necessary and proportionate" measures. Though the "get tough" rhetoric played to political advantage, it led to some poor policy choices grounded more in ideology than in evidence. As a consequence, the number of federal inmates climbed to historically high levels, time spent behind bars before release increased, parole grant rates declined and prison living conditions deteriorated.

Photo of a Segregation range

Photo of an Inmate canteen

Under the previous government, CSC's community safety role was prioritized. Public safety was entrenched as the foundational or pre-eminent purpose of the federal correctional system, eclipsing other equally legitimate correctional purposes such as community reintegration, offender rehabilitation or even safe and humane custody. New funding favoured institutional over community corrections; practice tilted in a decidedly law enforcement direction. Today, the equipment, training, weapons, uniforms and deportment of front-line officers looks a lot more like policing or military than correctional services. There are, for example, more drug detector dogs working in federal penitentiaries than in the entire Canada Border Services Agency. In higher security institutions, primary duties are more frequently conducted through static measures like control posts, electronic barriers and surveillance cameras. Staff spend a great deal of their time monitoring inmate activity on screens. The distance and separation between keeper and kept has increased; the scope of dynamic interaction and opportunity for meaningful engagement outside of regular rounds and security patrols has narrowed significantly. The culture and infrastructure of corrections has hardened. These have not been progressive changes for the profession.

Photo of Yard fencing

Photo of a Sweat lodge in a maximum security yard

Photo of Corcan shops

Photo of Institutional libraries

While I recognize that safety and security of both staff and prisoners is paramount, beyond a certain threshold security measures can be counter-productive, hindering rehabilitation and reintegration efforts. Overly restrictive environments, too few programs, disruptions in routine, too much time locked up, poor and outdated infrastructure and even lack of attention to simple things like adequate food generate inmate dissatisfaction and dissension. If tension is allowed to build in a prison context it can easily boil over into acts of individual or collective violence.

Photo of Segregation "yards" at Matsqui Institution

My investigation into the deadly riot at Saskatchewan Penitentiary in December 2016, a full account of which is featured as a special focus in this report, is a case study in prison violence. It is equally a demonstration in public transparency and organizational accountability. The findings and conclusions of CSC's internal National Board of Investigation (NBOI) and report into the riot to the effect that it was a random, spontaneous, unpredictable and unforeseen event raised a series of red flags with my Office. These concerns coalesced around the adequacy and appropriateness of CSC investigating itself in the aftermath of a serious incident. That the Service could convene and investigate this incident, which left one inmate murdered, two seriously injured after being assaulted and several others sustaining injuries from shotgun pellets used to quell the riot, without mentioning or coming to terms with the fact that the ranges that incited or instigated riot were overwhelmingly occupied by Indigenous inmates (85%) is perplexing to say the least. More troubling perhaps, the silence on the Indigenous composition and gang dynamics behind the Sask. Pen. riot was allowed to stand uncorrected in the public record of these events.

Photo of an Institutional kitchen

The acts and omissions that led to these oversights serve as further reminders that the Service lacks sufficient and dedicated senior leadership (Deputy Commissioner level) to maintain sustained focus on Indigenous issues in federal corrections. This must be addressed. I have also recommended to the Minister of Public Safety that additional assurance measures are required to enhance the integrity and credibility of investigations mandated by law into serious incidents in federal prisons, inclusive of major disturbances (riots) resulting in injury or death, suicides in segregation and use of force interventions leading to serious bodily injury or death.

Photo of a Segregation cell with plexiglass covering

Photo of a Segregation range

Photo of Saskatchewan Penitentiary post-riot

Many of Canadas prisons, including Sask. Pen., which first opened its doors more than a hundred years ago, are outmoded or have long since outlived their original purpose. Some penitentiaries continue to carry forward an earlier punitive philosophy. Even the relatively new maximum security units tend to feature physical infrastructure and environments that are sterile, austere, barren and demoralizing. Opportunity to engage in meaningful or humane interaction is minimized by design and intent. Unfortunately, the elements of modern prison or public building design lots of light, single accommodation in rooms or cells that the occupant can open with a key, vibrant program and service spaces adapted to offender needs, access to actual outdoor greenspaces, even texture and colour have so far failed to be incorporated in the most "modern" of CSC facilities, even though these features are known to have a significant impact on rehabilitation, public safety, and staff and offender morale.

To give but one example of how prison design influences behaviour, during a visit to a maximum security unit this past winter I was shown an Indigenous sweat lodge that was entombed in snow, enclosed in a cage and covered over in razor wire. By all appearances, it looked as if the far corner of the desolate "yard" where the lodge was located had not been used in quite a long time (to be fair, it was the middle of a cold Prairie winter). That this situation shows little respect for Aboriginal culture and spirituality appeared rather obvious. Making the opportunity to participate in Indigenous spirituality part of the maximum security experience does not, in any way, mitigate its more dehumanizing and oppressive features. Caging or warehousing people has no redeeming public safety value and is contrary to effective corrections.

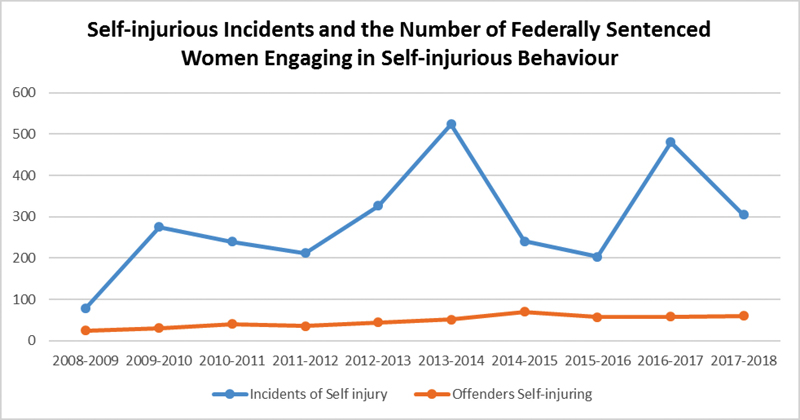

Correctional administrators and correctional officers know only too well that idle hands and minds behind bars can lead to trouble. Keeping inmates occupied and engaged in meaningful and remunerated work, upgrading their educational qualifications or having them participate in correctional programming contributes to a healthier, more productive and safer environment for staff and inmates alike. Though research and experience tell us that an occupied and engaged prisoner is less likely to cause trouble or be disruptive, I am often dismayed by how much time inmates seem to spend idle, locked up or alone in cells. It is no coincidence that the majority of security incidents occur in maximum security institutions; there are few programs, activities and interventions being offered in these settings. Further, we know that the majority of self-injurious incidents occur in the most isolated areas of the prison, namely, solitary confinement, observation and clinical seclusion cells. Too much idle time leads to incidents.

As noted later in my report, though most offenders do not have a grade 12 education or its equivalent when they enter prison, the wait list to get into programs can stretch exceedingly long; some serve their sentence and are back on the street without ever stepping into a classroom. As Victor Hugo is credited to have said: "He who opens a school door, closes a prison". I absolutely agree. And to be perfectly clear: cell studies are a poor substitute for the community of learning. CSC educators know that a prison classroom has a normalizing and civilizing influence; a prison only becomes a "school of violence" if there is little else to occupy a prisoners time. The Correctional Service can and should do more to bring the full reach of online learning platforms and enabling tools and devices (in-cell tablets, monitored email and Internet access) into prison. Public safety depends on it.

Corrections is not just about prisoners or prisons; careful attention and consideration must also be paid to staff. The lesson to emerge from maximum security Edmonton Institution this past year is that staff practices that undermine or degrade human dignity sexual harassment, bullying, discrimination can lead to a toxic work culture. A workplace that runs on fear, reprisal and intimidation is highly dysfunctional; it is the antithesis of modeling appropriate offender behaviour. Though I am encouraged by the establishment of a 1-800 line for CSC staff to report workplace harassment and wrongdoing, if staff disrespect, humiliate or disabuse each other one can only imagine how they might treat prisoners. It is no secret that some of the more problematic institutions in terms of lockdowns, incidents, use of segregation and overall compliance also have a checkered history of labour relations. I have no power or authority to investigate labour relations issues, but when staff actions or misbehaviour negatively impacts offenders it is perfectly within my remit to take appropriate action.

Throughout this reporting period, I am reminded that an outside human rights lens is sometimes required to challenge operational decisions. I would note that the removal of the outdoor cages in the segregation "yard", also at Edmonton Institution, (media reports referred to them as "dog kennels") occurred 24 hours after photos appeared on the front pages of Canadian newspapers.

I take seriously the statutory powers and authorities invested in the Office, including the right to enter and conduct inspections of federal penitentiaries, Footnote 1 not least because what happens behind prison walls remains largely hidden from public view. In function and design, prisons are a secretive and closed world, preoccupied as much with keeping prisoners in as they are with keeping everybody else out. Even in the most advanced democracies, the potential for abuse of state or correctional power remains. It is in that sense that I am directing my investigative staff to more rigorously apply the powers of inspection that Part III of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act confers. The Office's website now features a photogallery more fully depicting, warts and all, the everyday reality and experience of incarceration in Canada. Staff will also be given more practical training on how to conduct prison inspections health, hygiene and cleanliness being among the first priorities. These are some of the ways in which I intend to strengthen the quality, integrity and relevance of the Office's work and public reporting.

While external oversight provides public assurance, it does not guarantee that human rights violations are always detected, remedied or prevented. The rule of law that follows a person into prison must also be internalized. In nearly every aspect of correctional performance, CSC's internal monitoring mechanisms and review frameworks are nowhere as transparent, rigorous or effective as they should be. As a recent internal audit reminds once again, the internal inmate complaints and grievance system is broken, ineffective, dysfunctional, and, in my opinion, likely beyond repair or salvage. For grievances that reached national headquarters (NHQ) for a final decision, the average response time was 217 working days for "high priority" cases, and 281 working days for "routine priority" grievances. National reviews maintained the institutional decision in 97.9% of all cases. Chronic backlogs persist and even the unreasonably protracted response times laid out in CSC policy (not law) are not met 45% of the time. This is not a system that can be relied upon to provide assurance or feedback on CSC operations in real-time.

As my report on the Sask. Pen. riot demonstrates, there are systemic weaknesses in the means and manner in which the Service investigates itself in the aftermath of a serious incident. The findings, lessons learned and recommendations that emerge from its National Board of Investigation (NBOI) exercise rarely match the seriousness of the incidents under review major disturbances, assaults, riots, serious bodily injury and deaths in custody. These reports are not shared publicly; even internally, circulation seems unnecessarily restrictive.

In fact, the NBOI process, which is intended to promote wider learning, prevention and improvement through peer and investigative review, has become seriously compromised. Conclusions that reflect poorly on the Service are contained. Though findings from the NBOI process are not intended to be used in disciplinary proceedings, the bar that has been established to protect their integrity has now become a barrier to fully investigating the underlying causes of recurring incidents.

These issues are systemic. The impulse to contain bad news runs deep. Internal reviews, investigations and audits focus almost exclusively on policy compliance even the preventable deaths of Ashley Smith and Matthew Hines failed to raise issues of managerial responsibility or corporate accountability. At the national level, there are not enough senior management eyes looking at decidedly high-risk activities and interventions: use of force, complex mental health cases, suicidal and self-injurious behaviour, to name but a few. The Service continues to assume the risk of running prisons without 24/7 health care coverage. There are only a handful of resources at national headquarters dedicated to conducting national-level reviews of use of force interventions. It is not clear how or if CSC leadership can be assured that the more than 1,200 recorded use of force incidents that occurred last year were all managed lawfully, in accordance with principles of proportionality, restraint and necessity.

It seems to me that an incoming Commissioner has cause to be concerned about the effectiveness of CSC's internal monitoring and performance mechanisms, including the capacity of the Service to implement lessons learned and sustain corrective actions arising from internal audits, reviews, evaluations and investigations.

- I recommend that the incoming Commissioner of Corrections initiate a prioritized review of the effectiveness of internal monitoring and performance mechanisms, inclusive of use of force reviews, the National Board of Investigation process, inmate complaint and grievance system, staff discipline, audits, evaluations, communications and public reporting functions.

As the final part of my now admittedly long message to a new Commissioner, I would emphasize that correctional practices, services and programs must be respectful of and responsive to the needs of diverse groups. The face of corrections continues to diversify and evolve. This diversification is largely attributable to the sustained decline in the proportion of Caucasian offenders, which is more than matched by new and returning admissions to federal custody of Indigenous people. Today, a little over 50% of the inmate population is Caucasian, an overall numerical decline of 20% since 2009. This decline reflects falling serious crime rates, and mirrors trends and demographics of a majority society that is aging. At the same time, parole grant rates are trending upward, recovering from a period of long and steep reversal under the previous government. Fewer admissions to custody and more releases from prison would suggest that the corner on the "lost decade" may have finally been turned. Except for increases in Indigenous people and federally sentenced women, these are largely positive indicators.

Fortunately, the legislative tools required to manage diversity behind bars are in place, but they must be accessed and exercised as Parliament intended. The Corrections and Conditional Release Act makes specific reference in its principles to respect and fair treatment as well as prohibited grounds of discrimination. Special provisions are embedded in primary legislation for federally sentenced women and Indigenous offenders. Mental health, which sadly is a growing and prominent feature of prison life, was added in 2012 as a specific group requiring extra attention and protection. The Canadian Human Rights Act was also recently amended to include gender identity and gender expression as prohibited grounds of discrimination. In the reporting period, the Service finally moved to replace discriminatory policy and practices that prohibited institutional placements based on gender expression rather than sexual identity.

There remain, of course, some exceptions to the larger forces and drivers of correctional growth. In the Prairie Region especially, young Indigenous men and women continue to cycle through the system unabated. Though vast in geography and small in population, the Prairie Region is leading the country in offender growth. Not coincidentally, it is also the region that posts the highest proportionate rates of use of force, segregation, self-injurious and other incidents behind bars. Indigenous over-representation in corrections continues to set new historic highs now 28% overall and 40% for federally sentenced women. Indigenous offenders continue to serve proportionally more of their sentence in prison before release and in higher security settings than their non-Indigenous peers. They more often fail on conditional release and reoffend at much higher levels than their peers. These indicators and outcomes belie CSC's claim that it bears no responsibility for the morass of Indigenous over-incarceration. While it is true that the Correctional Service is at the receiving end of the criminal justice system, it serves no purpose to continue to deny factors that fall squarely within its remit to positively influence and change for the better.

The issues and themes that run through this report accountability, transparency, openness, leadership are informed by the visits, reports and investigations completed by my staff through the reporting period. Though my opening message is intended for a new Commissioner, the findings and issues collected and documented in this report come from the thousands of inmate complaints and contacts received and responded to each and every year by my staff without fail. Although I may sometimes express a difference in view or point of emphasis with the Service, my Investigators continue to be graciously received and well-served by Wardens and their teams all across this extraordinary land. Let me close this message on a positive note by saying how pleased I was to learn that the CSC has finally agreed to introduce an evidence-based program of safe prison needle exchange, a recommendation initially made by my predecessor, Mr. Howard Sapers, in his first Annual Report in 2003-04.

I feel privileged to lead and serve as Correctional Investigator. Regardless of who is chosen as the next Commissioner of the Correctional Service of Canada, I trust we can both learn and profit from the exemplary dedication of our respective staff members who serve all Canadians, especially and uniquely those who have been deprived of their liberty. When all is said and done, the OCI and CSC serve a common purpose. We should remain focused on that shared goal.

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

June 2018

1. HEALTH CARE IN FEDERAL CORRECTIONS

Update on Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) in Corrections

In my 2016-17 Annual Report, I reiterated concerns with CSC's draft Guidelines for Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID), which were provided to my Office for comment. My concerns can be summarized as follows:

- Policy and practice in implementing MAID legislation in federal corrections should be guided by compassionate and humanitarian interests.

- The decision to seek medical assistance in dying should be made, to the extent possible, while the palliative/terminally ill individual is in the community, preferably on parole by exception status (compassionate release).

- Consideration of the unique circumstances that incarceration imposes that limit an inmate/patient's option(s) to end life at a place and time of their own preference and choosing.

- Need for a Patient Advocate to protect inmate patient's rights and ensure they fully understand and meet the eligibility criteria of MAID.

On November 29, 2017, CSC promulgated internal guidelines governing how MAID applies to federally sentenced individuals. Footnote 2 I remain concerned that these Guidelines do not adequately meet the areas of concern or recommendations made in my 2016-17 Annual Report. Although the Guidelines state that MAID will be guided by "patient-centered care, compassionate and humanitarian principles", and assume that "the MAID procedure will be completed external to CSC", it is unsettling that an exception was included allowing the inmate/patient to request and receive the procedure in a federal correctional facility. In follow-up correspondence to the Commissioner (February 12, 2018), I stated that I simply cannot imagine a scenario where it would be considered acceptable to allow an external provider to end the life of an inmate in a federal penitentiary. The optics (and practice) do not seem right.

In response to my concerns, the Commissioner explained that:

- The decision to include an exception was made in order to "maximize" patient choice; and

- MAID providers have a "professional obligation" to ensure that the inmate patient's request is voluntary and informed before the procedure takes place.

Regarding the first point, prisons are environments where autonomy, free will and choice are restricted by the fact of incarceration. Ensuring that consent is informed and voluntary in such settings can be challenging. In a prison, compliance with authority is not only expected, but routinely compelled or enforced. It is in the context of incarceration and its inherent restrictions on choice that the existing Guidelines raise fundamental ethical and practical concerns. Issues of free, voluntary and informed consent must be front and centre of MAID governance in corrections; these rights must be acknowledged and respected.

As to the Commissioners second point, I have no doubt that the vast majority of health care staff both employed and contracted by CSC act with professional and ethical integrity in advocating for and carrying out their primary health care duties. This does not, however, absolve CSC from safeguarding the principle of clinical independence in the policy and rules that govern health care staff. These points are addressed later in this chapter. It is my belief that CSC should be removed from the position of being the enabler or facilitator of MAID. There should be no exceptions provided for or written into policy as it conflicts with CSC's mandate to preserve and protect life behind bars. MAID should only be performed by registered external health care providers and never in a facility under federal correctional authority. To the extent possible, a hastened death should be dignified.

To illustrate the issues at stake, the following case study examines the first case of a federal offender to receive MAID. It should be noted that the Service is not required, by law, to conduct an internal investigation (or mortality review) following a MAID procedure. I fail to understand the reasoning behind this exclusion, but unfortunately I have no authority to change the law that enshrines it. In my view, it does not rise to the same level of transparency and scrutiny that these issues attract in the rest of Canadian society and law. Notwithstanding, there are some clear learning points that emerge from the first case of MAID in federal corrections. These points are, by and large, informed by the unique status that federally sentenced individuals occupy in law.

Case Study

First Case of Medical Assistance in Dying in Federal Corrections

- The inmate was on palliative care for more than a year, suffering from a terminal illness.

- The Case Management Team started to work on a section 121 application for parole by exception (compassionate release) shortly after terminal diagnosis. The request was rejected by the Parole Board of Canada one year later.

- The inmate requested medical assistance in dying at a Regional Hospital under CSC's authority, with a physician who was under contract with CSC. It is unclear if the inmate chose MAID because he was refused compassionate release.

- Two evaluations took place, and the inmate met MAID criteria. The physician who conducted the evaluations was not under contract with CSC.

- A date was chosen by the inmate, and family members were permitted to visit him at the CSC Regional Hospital on a number of occasions in advance of the procedure.

- On the chosen day, the inmate was escorted to an external community hospital by two armed correctional officers in an adapted medical transport. The inmate was restrained. Once in the hospital room, the restraints were removed. The inmate was left in the room with pre-approved family members.

- According to CSC reporting, the officers providing security escort waited "at the back, near the entrance". (Note: the wording in CSC's report is not clear as to whether the officers stayed in the room or just outside the room).

- According to CSC, "the physician who performed the procedure, while under contract with CSC when he conducted the original assessment, was operating as an employee of the hospital in which the procedure took place, and not as a CSC physician".

Corrections and Conditional Release Act , Eligibility for Parole

Exceptional Cases

121 (1) [...] parole may be granted at any time to an offender

(a) who is terminally ill.

(b) whose physical or mental health is likely to suffer serious damage if the offender continues to be held in confinement.

(c) for whom continued confinement would constitute an excessive hardship that was not reasonably foreseeable at the time the offender was sentenced; or

(d) who is the subject of an order of surrender under the Extradition Act and who is to be detained until surrendered.

Exceptions

(2) Paragraphs (1) (b) to (d) do not apply to an offender who is

(a) serving a life sentence imposed as a minimum punishment or commuted from

a sentence of death; or

(b) serving, in a penitentiary, a sentence for an indeterminate period.

MAID Should be facilitated using section 121 releases

In cases of terminal illness where death is reasonably foreseen, Footnote 3 access to MAID would best be facilitated through section 121 or other conditional release mechanisms. End-of-life planning decisions, such as MAID, should ideally be made by parolees in the community, not inmates in a prison. Though CSC Guidelines for MAID state that all early release options are to be considered, none are actually elaborated. Compliance with organizational policy is undermined when directions are not clearly and explicitly stated. This is perhaps the reason why CSC saw the need to write into policy that MAID could be "exceptionally" provided in a federal facility. I would argue, however, that unintended negative impacts are far more likely if exceptions for the delivery of MAID in federal institutions are written into policy, than if early release mechanisms for terminally ill inmates were more clearly articulated and actively monitored.

&

&

Photo of a Health care center

Photo of a Walking cane

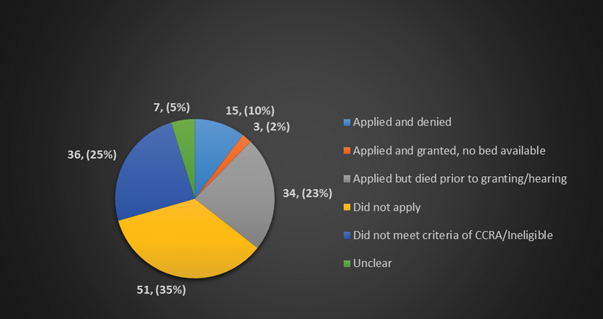

As CSC's latest Annual Report on Deaths in Custody 2015/2016 (November 2017) affirms, Footnote 4 section 121 release by exception applications are under-utilized, often denied, and rarely successful even though many terminally ill individuals subsequently end up dying in a federal facility. Recent Canadian-based research has clearly demonstrated that, despite the aging and increasingly chronically ill populations behind bars, compassionate releases have barely been used, and even more exceptionally on humanitarian grounds. Footnote 5

Inmates offered s. 121 releases who subsequently died of natural causes while incarcerated (2009/10 2015/16)

Notes:

1. The numbers reported above exclude unexpected deaths.

2. There were 254 natural deaths in federal custody from 2009/10 to 2015/16.

3. The actual number of successful s. 121 releases during this period is not known.

Bill C-14 was intended to reduce suffering and increase the dignity of end-of-life care. CSC would be better positioned to achieve this objective through advancing section 121 "parole by exception" release planning and ensuring applications to the Parole Board of Canada are completed in the timeliest manner possible. Though release decision making is clearly outside the scope of CSC's jurisdiction, terminally ill individuals should not have to die in prison simply because their cases were not processed or brought before the Parole Board in a sufficiently complete or timely manner. If capacity in the community to manage a terminally ill or palliative patient is lacking, then CSC should engage with external service providers and reallocate funds that would otherwise be spent on unnecessary (and costly!) incarceration. If CSC were to ensure that capacity was available, the Parole Board of Canada would be in a better position to support a release plan that would allow the individual to serve the remainder of their sentence with dignity in the community.

I make the following recommendations:

- I recommend that there be no exceptions written into or provided for in CSC policy allowing MAID to take place in a facility under federal correctional authority or control. Internal policy should simply state that a request for MAID from a federal inmate who is terminally ill will be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

- I recommend that, in cases of terminal illness where death is reasonably foreseen, there should be proactive and coordinated case management between CSC and the Parole Board of Canada to facilitate safe and compassionate community release in the timeliest manner possible.

- I recommend that the CSC develop arrangements with external hospice and palliative care providers in each Region to ensure adequate and appropriate bed space is in place to release palliative or terminally ill patients to the community.

Clinical Independence and Prison Health Care Governance

Photo of a Walker

I have previously discussed my position on clinical independence and the mixed or "dual loyalties" that health care providers constantly face working in a correctional health care context. Footnote 6 As the MAID discussion illustrates, there are ethical, organizational, operational and administrative issues that must be considered in ensuring no undue interference with the task of advocating for and protecting the physical and mental health care of inmate patients. It is important to recall that the "sole task of health care providers in correctional settings is to provide health care with undivided loyalty to the patient's, with unrestricted clinical independence, acting as the patient's personal caregiver without becoming involved in any medical actions that are not in the interest of the patient health and well-being". Footnote 7 These areas are not as well-articulated, grounded or protected in CSC health care administration, policy and governance structures as they should be.

Photo of a Health care sign

There are many areas of correctional health care practice that give rise to clinical role conflicts or ethical dilemmas, where clinical independence and professional autonomy may be impaired or impeded, or where health care providers may feel compelled to follow correctional authority rather than health care rules. Some practical examples of dual loyalties of health care staff include:

- Assessing inmates as medically or mentally (un)fit to participate in work or to extend solitary confinement placements, either for disciplinary or administrative purposes.

- Applying, removing, adjusting or monitoring physical restraints to prevent self-injurious behaviour.

- Conducting body cavity searches where there are no medical indications for such actions.

- A restrictive National Drug Formulary that may limit physician prescribing and treatment options.

- Informed versus implied or compelled consent to treatment.

- Post-use of force health care assessments.

The issues of concern here relate less to health care professionalism/performance and more to the governance of health care staff. The fact of the matter is that CSC health services are not fully independent or separate from the rest of the organization. Health care personnel working in federal penitentiaries are employed by CSC not the Health Ministry. This situation necessitates robust accountability and rigorous oversight duly exercised at the national level. A recent article clearly sets out the stakes and interests at play, in the international and domestic contexts:

Clinical independence is an essential component of good health care and health care professionalism, particularly in correctional settings...where the relationship between patients and caregivers is not based on free choice and where the punitive correctional setting can challenge medical care. Independence for the delivery of health care services is defined by international standards as a critical element for quality care in correctional settings, yet many correctional facilities do not meet these standards because of lack of awareness, persisting legal regulations, contradictory terms of employment for health professionals, or current health care governance structures. Footnote 8

The crux of the matter boils down to the fact that role conflicts and misunderstandings between health care and custodial staff are common and everyday occurrences. Examples abound: population movement schedules determine health care clinic hours; when or if an inmates medical escort takes place is dependent on staffing levels; who provides care or how it is provided in a prison setting is not a matter of patient choice.

Photo of a Counselling/interview room

in maximum security

Photo of a Wheelchair accessible cell and Photo of a Health care unit

In my last Annual Report (2016-17), I called on the Service to conduct a compliance review of its health care services, policies, practices and procedures against the most widely respected and comprehensive collection of international prison human rights standards, the revised United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (now known as the Mandela Rules). The Mandela Rules state that clinical decisions may only be taken by the responsible health-care professionals and may not be overruled or ignored by non-medical prison staff. Though a review of the Mandela Rules was purportedly conducted and completed, in response to an Office request for an update, CSC provided no documentation, report or findings to corroborate its claim that CSC health care services are compliant with the Mandela Rules. Saying or believing that the Service is compliant with domestic or international rules and standards is different from demonstrating it. As with many other activities within CSC, transparency would go a long way towards ensuring that health care standards behind bars are demonstrably met.

Best Practice Peer Offender Prevention Service (POPS)

- The Peer Offender Prevention Service (POPS) was created at Stony Mountain Institution (SMI) in December 2009 in response to the deployment of the Institutional Mental Health Initiative. It is a confidential, peer-based program that provides SMI with comprehensive crisis intervention, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

- POPS is offered throughout the institution, servicing segregation, all three levels of security (minimum, medium, maximum) and all sub-populations. At any given time, SMI has three to four offenders (typically "lifers") occupying a POPS peer support role.

"It's a great opportunity for me as a POPS to be called to different situations involving inmates, who are at a loss and need somebody to speak with. When they talk, sometimes there's a connection, a bond, and we can discuss the situation and make them feel at ease."

- Testimonial

- Training for POPS is facilitated by a range of community-based agencies and has a wide focus, including anxiety, depression, suicide prevention, general mental health, trauma, etc.

- By offering a credible and reliable response for offenders requiring both temporary and on-going supports, POPS assist institutional clinicians and operational staff.

- POPS has helped minimize attempts of self-harm and their engagement has assisted vulnerable offenders to remain in general population.

The Service has recently established a National Medical Advisory Committee comprising, among others, CSC's Senior Medical and Psychiatry Advisors, as well as other senior administrative personnel. The Committee brings to life the challenges facing correctional health care professionals vis--vis their operational and administrative counterparts. Given that the Service relies on contracted medical staff to provide services, bringing together a body of health care professionals from a range of disciplines at all levels within the organization is an important initiative. It is encouraging that the Committee is engaged in some of the more difficult physical and mental health care issues facing the Service:

- Responding to the needs of an aging inmate population.

- Suicide prevention and intervention strategy.

- National clinical seclusion policy.

- Revision of the mortality review process.

- Standards of care.

While there is no shortage of work for the Committee to consider, CSC would be encouraged, as a matter of priority, to advance and enhance clinical independence in prison health care, which could be expected to lead to more timely access and higher quality service delivery.

Photo of an Accessible shower

- I recommend strengthening CSC's health care governance structure through the following accountability and assurance measures:

- Complete separation of health care budgets from prison administration.

- More team-based and shared models of primary care, including closer monitoring, charting and follow-up of individual treatment plans.

- Practical and ongoing judgement-based and ethical training of correctional health care professionals.

- Coordination, oversight and monitoring of transitions in physical and mental health care (e.g. transfers between CSC facilities, releases to the community, transfers to external health care providers, transfers to and returns from Regional Treatment Centres).

- A system of regular peer reviews, medical chart audits and evaluations of medical staff conducted at the national level.

Independent Review of the Regional Treatment Centres

Photo of a Cell door

The Correctional Service of Canada operates five Regional Treatment Centres (RTCs), which primarily serve as inpatient mental health facilities or psychiatric hospitals. Today, there are fewer than 200 psychiatric hospital beds for men and 20 inpatient psychiatric beds for federally sentenced women. According to a recent external evaluation commissioned by the Service, Footnote 9 the overall ratio of clinical staff to psychiatric bed ratios (Psychiatrists, Psychologists, and Nurses) is well below expected or acceptable standards for inpatient psychiatric hospital care. The report found the following: 1 to 48.5 beds for Psychiatry; 1 to 32.5 beds for Psychology and; 1 to 51 beds for Nursing. According to the independent reviewer, these low staffing ratios to patient needs can result in the overuse of segregation and clinical seclusion practices.

Other findings of concern emerging from the external evaluation of the RTCs include:

- Correctional and mental health staff are lacking in the skill sets required to deal with forensic patients.

- The selection of security personnel (Correctional Officers) to work in the Treatment Centres seems unrelated to the needs of patients and is inconsistent with a psychiatric hospital setting.

- Physical infrastructure is "seriously problematic" and unsatisfactory for the delivery of mental health services.

- The assessment tools used to screen for mental health conditions and to admit patients to the Treatment Centers are regarded as limited or not clinically relevant.

- Growing problems with the accommodation of older ("geriatric") patients.

A number of other concerns were identified regarding training and recruitment practices in the Treatment Centers:

- The need to train correctional officers to enhance their ability to identify individuals suffering from mental illness to ensure they are not "lost in the system".

- Training for mental health staff "related to dealing with seriously mentally ill inmates in a secure environment".

- Recruitment of mental health professionals who have "undergone subspecialty training in Forensic Psychiatry", as they would be best suited to working in secure environments.

According to the review, because inmates are totally dependent on CSC for the basics of life, the Service is obligated to provide essential health care and reasonable access to non-essential mental health care. In the reviewer's assessment, the inadequate delivery of non-essential mental health care in CSC facilities is extremely likely to expose the Service to class action lawsuits and constitutes a Charter violation.

These and other findings generally reflect areas of concern identified by the Office over the years, though the external review contains some bold new proposals for reform. For example, the report recommends replacing the Treatment Centres with state-of-the-art, custom designed, inpatient facilities (though I am of the view that re-profiling existing resources and outsourcing the care of an additional two or three dozen complex needs men and women to external forensic hospitals is a more practical use of resources than new builds). The report cautions that, while these new facilities could be run by CSC, the care aspect should be left to the experts (in forensic psychiatry). The suggestion that acute or inpatient mental health care be outsourced should not be taken as a slight on the quality of personnel working within the Treatment Centres; it is rather the reviewer's assessment that the infrastructure, staffing and operational models currently in place do not adequately meet the complex needs of some patients. I concur with that conclusion, underscored and exemplified by the case below. Based on the findings of the Bradford report, and in addition to measures that remain outstanding on access to mental health care, I make this new recommendation:

- I recommend that CSC ensure security staff working in a Regional Treatment Centre be carefully recruited, suitably selected, properly trained and fully competent to carry out their duties in a secure psychiatric hospital environment.

Case Study

Managing Complex Mental Health Needs

Photo of a bed used as part

of the Pinel restraint system

The Office investigated an incident involving a dual status offender (a concurrent sentence that falls under the jurisdiction of both CSC and the province) at one of the Regional Treatment Centres. This patient requires a high level of care due to significant mental health issues, serial and escalating self-injurious behaviour. The patient attempted to self-injure while he was restrained in a four-point Pinel Restraint System (PRS) and Posey Mitts.* A Correctional Officer assigned to monitor the patient deployed pepper spray in response. The Office found that this use of force was inappropriate and unnecessary. An internal use of force review suggested that correctional staff were stressed and burned out from supervising the patient. Patients with this level of need should be treated in a facility designed for this purpose, where responses are health care-driven and mental health professionals conduct interventions and monitoring of patients instead of security personnel.

*Posey mitts are used to prevent further self-injury to existing wounds.

Patient Background

- Transferred over 20 times throughout sentence between provincial psychiatric institutions and CSC facilities.

- Subject to frequent internal disciplinary measures, and criminal charges (facing a longer sentence as a result).

- Over 200 documented incidents of self-injurious behaviour.

- Self-inflicted injuries often require surgical attention at an outside hospital.

- Subject to over 50 use of force interventions.

A Patient Advocate System for Federal Corrections

In my last Annual Report, I recommended the implementation of a separate, dedicated Patient Advocate system for federal corrections. This recommendation was made in context of medical assistance in dying, where an independent oversight mechanism could ensure that the inmate-patient's consent is unimpeded and voluntary. A Patient Advocate model, enabled to initiate and facilitate section 121 applications where appropriate, could help address many of the ethical, legal and human rights concerns that MAID raises in a correctional context.

The Commissioner's response to my latest MAID correspondence indicated that CSC plans to establish agreements with end-of-life care providers in each of the regions to act as independent Patient Advocates. I am encouraged by this initiative, although CSC has yet to provide specific detail about what is being proposed, or expected timelines. It is important to recall that the recommendation for a Patient Advocate model reaches far back in time before MAID. The Office's report entitled, Risky Business: An Investigation of the Treatment and Management of Chronic Self-Injury Among Federally Sentenced Women Final Report (September 30, 2013), first recommended that CSC should appoint an independent patient advocate at each of the five RTCs. This recommendation echoed a measure identified in the Ontario Coroner's inquest into the preventable death of Ashley Smith (December 2013). Specifically, the jury recommended that:

- CSC implement an independent Rights Advisor and Inmate Advocate (RA-IA) for all inmates, regardless of security classification, status, or placement. The institution will be responsible for advising all inmates of the existence of, and their right to contact, the RA-IA.

- That the RA-IA will be responsible for providing advice, advocacy and support to the inmate with respect to various institutional issues, including:

a) Transition into institutions;

b) Transfers;

c) Security classification, status, or placement;

d) Parole and release eligibility, including escorted and unescorted absences;

e) Temporary absences;

f) Use of restraints - physical and chemical;

g) Seclusion and segregation;

h) Complaints and grievances;

i) Consent to treatment and capacity to consent;

j) Consent to medication, including available alternatives;

k) Consent to disclosure of information; and

l) Institutional and criminal charges.

Photo of a Segregation range

The Service's uptake on accountability measures recommended by the inquest and this Office has been minimal, at best. There is currently a provision in Commissioner's Directive 709 (Administrative Segregation) outlining that, within 24 hours Footnote 10 of being admitted to administrative segregation, inmates with functional challenges related to mental health Footnote 11 will be informed of the right to engage an advocate to assist with the institutional segregation review process. There is no mention, in this policy or elsewhere, of who would perform the advocacy role let alone their degree of independence. In fact, CD-709 defines an advocate as a person who, in the opinion of the Institutional Head, is acting or will act in the best interest of the inmate. This is not independence of the kind that either the jury or this Office have in mind. The CSC has also been unable to demonstrate the effectiveness and frequency of use of its segregation advocacy provision.

It should be clear that, in the case of MAID, the obligation to ensure that the patient inmate fully understands, voluntarily requests and meets eligibility criteria rests with the medical or nurse practitioner. However, as previously noted, the issues involving free, voluntary and informed consent and clinical independence are magnified in a correctional setting and extend equally (if not more so) to offenders with mental health issues. Inmate patients often lack the ability to access timely and effective health and/or mental health services, which can negatively affect not only their well-being, but also their reintegration results. Therefore, CSC needs a Patient Advocate model to protect inmate patients' rights, assist the inmate patient to explore all available alternatives and to ensure they fully understand the implications of their decisions without compulsion.

- I recommend that independent Patient Advocates be assigned to each Treatment Centre, whose role and responsibilities include providing inmate patients with advice, advocacy and support and ensuring their rights are fully understood, respected and protected. The Patient Advocates could also serve as expert resources for other CSC facilities in each Region.

Update on Older/Aging Offenders

My Office, in collaboration with the Canadian Human Rights Commission, is actively investigating issues affecting older/aging offenders in federal custody and in the community. The Chief Commissioner and I expect our joint report to be publicly released in Fall 2018. In the meantime, the Service continues to consult and put together a framework that would promote wellness and independence of older persons in custody. Given that one-quarter of the inmate population is now aged 50 or older, this work needs to advance in a decidedly more prioritized manner. The needs and concerns of this growing, but still largely hidden and under-serviced population, are well known to CSC. It is time to finally move from consultation and discussion to implementation and action.

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

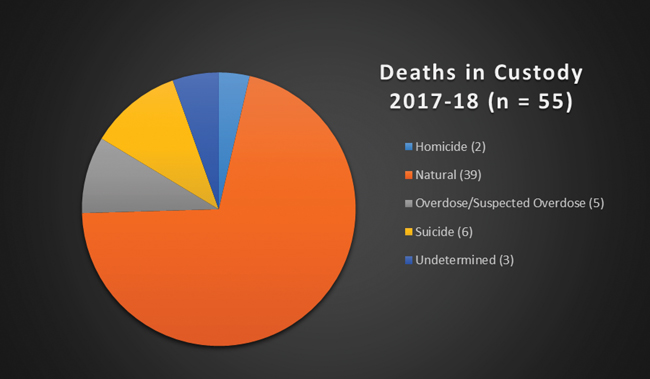

There were 55 deaths in federal custody in 2017-18. Most in-custody deaths last year (71%) occurred as a result of natural causes. The Prairie Region recorded the most deaths (16), followed by the Quebec Region (15). Two deaths occurred in the Regional Women's facilities. Both were from natural causes. Overall, Indigenous offenders accounted for 23% (13) of all deaths in custody, which is almost equivalent to their representation among the federal inmate population. The majority of Indigenous deaths were due to natural causes (8). Suicides accounted for 23% of all Indigenous deaths in custody in 2017/18, but only 8% of all deaths in custody among non-Indigenous inmates. Footnote 12

CSC's Annual Report on Deaths in Custody 2015/16

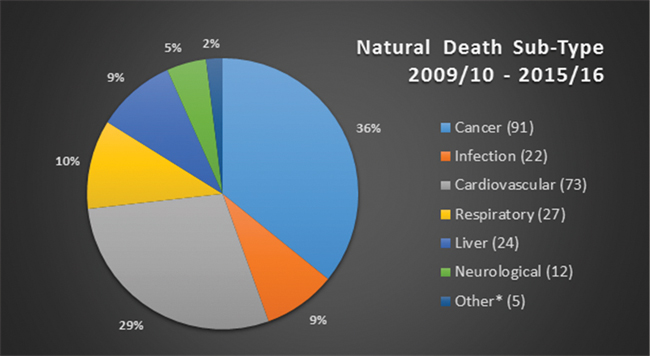

In November 2017, CSC released its third Annual Report on Deaths in Custody Footnote 13 . This report included statistical trends of deaths in custody since 2009/10. Among other results, this report substantiates many of the concerns previously brought forward by the Office, particularly with respect to aging/older inmates. Of all inmates who died in custody of natural causes between 2009/10 and 2015/16, most 91% (230 out of 254) were 45-years and older. Just over half were serving an indeterminate sentence. 50% were receiving palliative care at time of death. Average age of death from natural cause was 60 years.

Deaths in Custody 2017-18 (n=55)

Natural Death Sub-type 2009/10-2015/16 Pie Chart

*Also includes individuals where a specific natural sub-type was unavailable.

The report also provided details about the nature and cause of these deaths:

- 76% were related to either substance misuse or smoking;

- 49% had a mental health condition;

- 96% had a chronic health condition unrelated to the cause of death; and,

- 76% had between two and seven chronic health conditions.

Some concerning details were also reported with regard to non-natural inmate deaths (n = 132) between 2009/10 and 2015/16. For example, 71% (91) had an identified mental health disorder. 22% (28) were in segregation at the time of death. Nearly one third of suicides in segregation occurred in the Prairie Region.

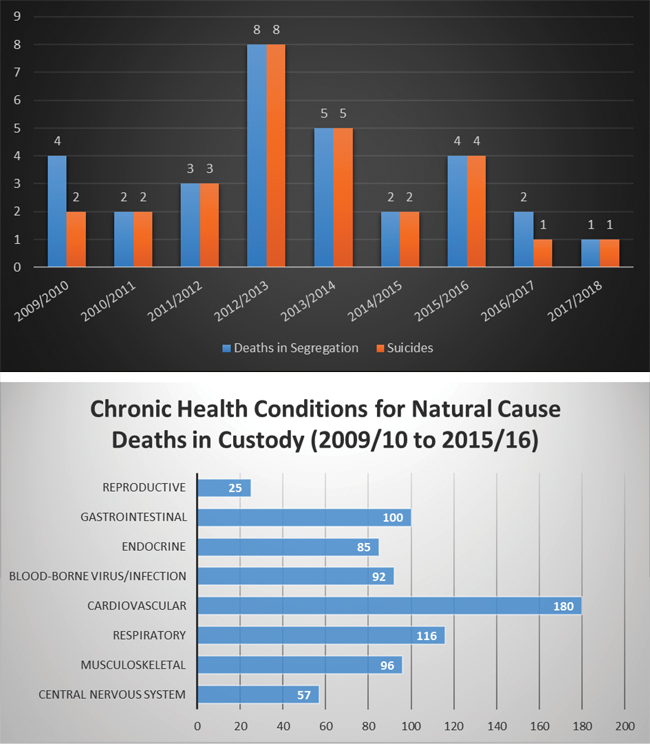

As depicted below, deaths in segregation have steadily decreased since 2012/13. Footnote 14 Even still, 90% of all non-natural deaths in segregation since 2009/10 were the result of suicides (the remaining were largely due to overdoses). Suicides in segregation represent 37% of all suicides since 2009/10.

Notes:

1. Totals will not add to the total number of natural deaths as offenders may have multiple types of chronic health conditions.

2. Results are accurate as of July 31, 2017.

3. The conditions are not necessarily related to the cause of death.

Despite highly disaggregated reporting (which also included the days of the week and times of the day when deaths are most likely to occur), CSC continues to fail to identify or advance meaningful, evidence-based recommendations focused on prevention of deaths in custody. Beyond a very brief thematic analysis of Board of Investigation recommendations, and a short mention of compliance issues, the report does not address any learning points or strategies that would prevent future deaths in custody. Given that the average age of death due to natural causes is 60 years, it is surprising that there is no learning or strategies advanced as to how CSC could mitigate what amounts to premature deaths behind bars. Little seems to be known about chronic illness in correctional facilities other than that the list of co-morbid conditions at time of death is often extensive. The report does not mention or identify any health care related concerns or considerations. Given that this is now the third Annual Report on Deaths in Custody , I am curious to learn what CSC is actually doing with the statistical information it is amassing. I am specifically interested in the Service's answers to the following questions:

- How is the annual report on deaths in custody exercise informing policy, practices and organizational strategies to prevent deaths in custody?

- How does this reporting reflect or differ from the Independent Review Committees that periodically assess CSC's performance in preventing non-natural deaths in custody?

- What is specifically being done to prevent suicide risk in segregation?

- Why do these reports fail to specifically address, assess or identify lessons learned or recommendations from section 19 deaths in custody investigations?

- On the basis of what still amounts to tombstone reporting and some trend analysis, how can Canadians be assured CSC is doing everything possible to prevent deaths in custody?

- How is the issue of premature mortality in federal prisons being addressed?

- How is death in custody data informing a National Strategy for older/aging offenders?

In the absence of substantive answers to these questions, I conclude that this exercise is devoid of context. It is definitively not a lessons learned, performance assurance or corporate accountability record, which this Office has long called upon CSC to produce and release publicly.

Follow Up from Fatal Response

On May 2, 2017, the Minister of Public Safety tabled my Special Report to Parliament Fatal Response: An Investigation into the Preventable Death of Matthew Ryan Hines. Matthew's death in May 2015 followed multiple uses of unnecessary and inappropriate chemical and physical force at Dorchester Penitentiary. The impact and implications of this tragedy are still being felt across the Service, inclusive of ongoing criminal proceedings against two officers. Matthew's death was a watershed moment in the history of Canadian corrections. It prompted a rare admission from the Service acknowledging that its actions and omissions contributed to Matthew's death. The Commissioner's apology was sincere. Footnote 15

Though the source is largely unacknowledged, the Service continues to revise policy and operational frameworks in significant areas touched by Matthew's death:

- Use of force intervention, situation management and incident response (new Engagement and Intervention Model replacing the Situation Management Model).

- Reconciliation of staff discipline and internal investigative processes (ongoing).

- Information-sharing and disclosure practices with families following a death in custody.

- Use of force training materials and methods to prevent similar tragedies, including acknowledgement that officers assume responsibility and accountability for the safety and

well-being of prisoners under their escort. - Higher level of scrutiny of disciplinary decisions related to use of force incidents resulting in serious bodily harm or death.

- New research into the potential linkages between use of inflammatory agents and in-custody death.

- Clarification and consolidation of the officer in charge position (Sector Coordinator).

For Matthew's death to have enduring meaning, not all of these reforms are as ingrained or entrenched as they need to become. CSC culture remains highly insular. Learning and critical self-reflection do not come easily or naturally to an organization whose first instinct is to contain or control bad news. It is encouraging that Matthew's death continues to prompt internal calls for reform and change. I remain convinced that more accountability and transparency is the way forward. It bears reminding that the manner and circumstances of Matthew's death would not likely have ever seen the full light of day had my Office, the media and Matthew's family not reported publicly. This, too, is one of the unstated lessons emerging from Matthew's death.

3. CONDITIONS OF CONFINEMENT

Use of Force

In March 2018, CSC completed an audit of the Situation Management Model (SMM) which, up until recently, was the framework by which staff responded to a security incident. Footnote 16 What is important about this audit is that it was assessing compliance of the policy, response and review framework that governs use of force interventions in CSC facilities. The audit is forthright and frank. It suggests that there is no shortage of compliance issues when it comes to how force is used, monitored and reviewed within the organization. The audit essentially consolidates several areas for improvement that my Office has been raising for years based on our own use of force reviews, investigations and incident monitoring:

- The use of force policy framework does not clearly define who is in charge when multiple staff members are responding to an incident.

- Guidance material is not in place for use of force reviews.

- Training on the use of force module is not consistently provided to staff.

- Performance monitoring and reporting is insufficient at the local, regional and national levels.

- Intervention plans are not always documented as required.

- First aid and physical assessments are not always completed following a use of force incident.

- The focus of the use of force reviews is not consistent across the country.

- Compliance issues and corrective action information are inconsistently documented.

The audit's findings raise several concerns, though three areas in particular stand out:

- Beyond ad hoc reports, there is no regular use of force performance monitoring and reporting being conducted at the national level (only 5% of use of force incidents are subject to a random review).

- Corrective action is not always taken as required, nor is it effective.

- Use of force reviews are not being completed within the required timeframes.

Problems in these areas mean that the same compliance issues repeatedly identified by my Office failure to deploy a hand-held camera, proper completion of post-use of force health care assessments, quality and timeliness of use of force reporting continue to occur without proper or sustained correction. As the audit finds, delays in completing reviews and identifying compliance issues weaken internal oversight of use of force incidents and increases the risk that inappropriate responses are not identified or addressed in a timely manner.

The audit is particularly blunt concerning staff response and behaviour when compliance issues are identified:

The corrective action that was taken for these issues was generally limited to management sending emails to staff member(s) involved, or providing a reminder of policy requirements We found that this type of corrective action was utilized regardless of the significance of the policy compliance Management indicated that while corrective action is taken, it is not very effective in improving compliance or changing behaviours and responses Management at the local level indicated that they try to take corrective action that is geared towards educating staff rather than disciplining them. However, we found this action does not appear to escalate to disciplinary action if the same issues persist. Footnote 17

These findings reiterate a major concern identified in my investigation into the death of Matthew Hines that the corrective or disciplinary actions identified through internal reviews do not match the seriousness of the incidents under review. The two processes post-incident investigation and staff discipline are not, in any meaningful way, linked or reconciled. While the review process is supposed to play a key role in ensuring the Service adheres to principles of accountability and transparency, I would suggest that there is not near enough senior management attention and eyes on what is a decidedly high-risk activity. There are only a handful of resources at national headquarters dedicated to conducting national-level reviews of use of force interventions. Only 5% of all use of force interventions are subject to a random review at the national level. There is simply no guarantee that even the most egregious use of force interventions make their way up to the national level. It is far from clear how or if CSC leadership can be assured that the 1,345 use of force incidents recorded last year were managed lawfully, in accordance with the principles of restraint, proportionality and necessity.

For its part, the audit recommends corresponding action in each of the areas of deficiency identified:

- Clarify who is in charge of controlling a response to a security incident.

- Provide guidance material for use of force reviews.

- Provide staff training on the use of force module in the Offender Management System.

- Monitor and report on performance at the local, regional and national levels.

- Ensure intervention plans are documented as required by policy.

- Ensure post use of force first aid and physical assessments are completed.

- Ensure use of force reviews are completed within required timeframes.

- Clarify the focus and intent of use of force reviews.

- Ensure corrective actions taken are effective.

- Ensure compliance issues and corrective action are consistently documented.

Use of Force Coding Project Initial Findings

CSC is required to provide all use of force documentation* to the OCI for review. The Office has initiated a project to code all use of force incidents using a variety of indicators (i.e. type of force used, where the incident occurred, age and race of inmates involved and security level where incident occurred). For the 16-month period between October 2016 and February 2018, 1,914 use of force incidents were coded. Findings include:

- The Prairie Region accounted for the largest proportion of use of force incidents (33.4% or 641 incidents), followed by Quebec (21% or 402 incidents), Ontario (19.8% or 379 incidents), Pacific (14.3% or 274 incidents) and Atlantic (11.3% or 218 incidents).

- The Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC) Prairies reported the most incidents (175), followed by Edmonton Institution (136), Ontario Regional Treatment Centre (124), Donnacona (123) and Kent Institution (114).

- Location of the incident:

- Most incidents occurred in maximum security (70.2%)

- 10% occurred in segregation

- 33% in a cell

- 20% on a range

- Demographic indicators:

- 10% of incidents involved one or more federally sentenced women.

- 8 incidents involved a transgender inmate.

- Most incidents involved an inmate 22-49 years of age. Approximately 9% involved an inmate 18-21 years of age and 8% involved an inmate 50 years of age and older.

- 47% involved at least one Indigenous inmate.

- 41% involved at least one inmate with documented mental health concerns.

- 13.6% involved a self-injurious inmate.

- 46% of incidents involved the use of inflammatory (pepper spray) or chemical agents.

- The deployment of the Emergency Response Team was identified in 7% of all incidents.

- In 62.4% of use of force incidents, CSC identified compliance issues related to the use of a camera usually related to the untimely deployment of a handheld video-camera.

* Documentation typically includes: Use of Force Report, copy of the incident-related video, checklist for Health Services Review of Use of Force, Officers' Statement/Observation Report, offender's version of the events and an action plan to address deficiencies.

Correcting these deficiencies is a tall order, especially considering that CSC's track record of fixing problems post-incident is not encouraging. With respect to use of force, it is compounded by the sheer volume, complexity and nature of the incidents. As my Office notes, over 40% of use of force interventions involve inmate(s) with a mental health issue identified or documented by the Service. 13.6% of use of interventions coded by my Office involved self-injurious behaviour; the overwhelming majority of these incidents involved the use of an inflammatory agent (pepper spray). Footnote 18

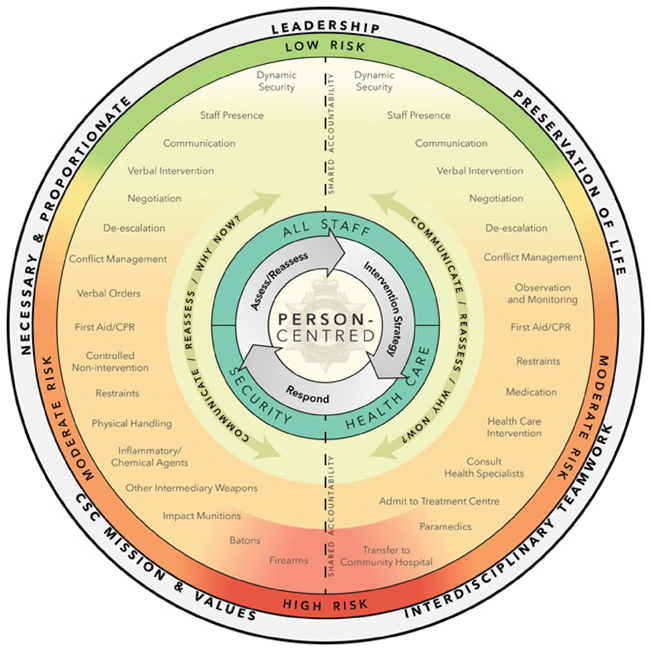

Engagement and Intervention Model

Office reporting confirms that fully one third of all use of force incidents in CSC facilities occur in cell. As CSC has acknowledged, where inmates are confined to a cell the situations in which such incidents occur may not pose an immediate risk or imminent threat or harm to either staff or inmate. Where the incident or situation occurs in contained areas, such as living units or cells, there may not even be the need to respond with force at all; certainly pepper spray should not be deployed as quickly or as pervasively as it has in the past. Risk assessment based on AIM principles A bility to carry out a threat; I ntent to behave or act in a specific manner; M eans to carry out or act on a threat has been lacking. Inflammatory agents (pepper spray) have been over-used and over-relied upon to induce or compel compliant behaviour, even when the risk is considered minimal. Verbal intervention skills and de-escalation techniques have been eroded or minimized.

Engagement and

Intervention Model (2018)

As use of force video recordings often depict, there can be a great deal of confusion during a use of force incident, especially when multiple staff members are called upon to respond. Up until recently, the policy framework failed to clearly define who should be in charge during these situations. By CSC's own admission, there has been an imbalance between security and health considerations. Incident management within CSC has been predominantly security-led and security-driven. Many of these issues lack of leadership and on-scene controller, multiple and unnecessary uses of pepper spray and failure to recognize and respond to a medical emergency in a timely and competent manner were in play in the events leading to the preventable death of Matthew Hines. My report called on CSC to immediately develop a separate and distinct intervention and management model to assist front-line staff in recognizing, responding and addressing situations of medical emergency and/or acute mental health distress. In response, two internal reviews the audit of situation management and the Security Branch's review and report on use of force within CSC Footnote 19 have come, more or less, to the same conclusion. Each confirms that a shift in response and behaviour in managing security incidents within CSC was necessary.

It is in that light that I am encouraged by the replacement of the previous Situation Management Model with the new Engagement and Intervention Model (EIM). It signals an important change in officer conduct and, just as importantly, a major shift in culture within CSC. Expectations that use of force situations will be managed with a heightened sense of scrutiny, diligence and enhanced review is welcomed by my Office. While it is still too early to determine if the new intervention model and attendant changes are having the desired impact or a sustained effect, the use of force intervention below contains case details eerily similar to those that led to the preventable death of Matthew Hines.