June 26, 2020

The Honourable Bill Blair

Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 47th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigators Message

National Issues – Major Cases and Updates

1. Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) – Case Reviews

2. Replacement of CSC’s Prisoner Escort Vehicles

3. Bill C-83 Reforms and Implementation

4. Use of Force Reviews – Egregious Cases

7. Edmonton Institution Update – Staff Discipline

8. Indigenous Corrections – Update

National Investigations

2. National Systemic Investigation on Therapeutic Ranges

Correctional Investigator’s Outlook for 2020-2021

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Annex A: Summary of Recommendations

Responses to the 47th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator

Correctional Investigator's Message

Dr. Ivan Zinger,

Correctional Investigator of Canada

My Annual Report this year looks and reads a little differently than previously. First, I am reporting out on three national-level investigations conducted in 2019-20:

- A Culture of Silence: National Investigation into Sexual Coercion and Violence in Federal Corrections

- An Investigation of Therapeutic Ranges at Male Maximum Security Institutions

- Learning behind Bars: An Investigation of Educational Programming and Vocational Training in Federal Penitentiaries

The publication of these investigations in an annual report reflects the direction in which my Office is moving – towards more systemic-level work. I am proud to feature these pieces in this year’s report, and will come back to put some emphasis on the learning and sexual violence reports.

Second, the chapters in which I typically organize and present my report have been replaced by a section entitled National Issues – Major Cases and Updates . Like the thematic chapters it replaces, this section serves as the documentary record of policy issues or significant cases addressed at the national level in 2019-20. Among other issues, in this section the reader will find an update on Indigenous Corrections as well as case summaries, findings and recommendations from investigations into Medical Assistance in Dying, use of dry cells, major use of force incidents, and an assessment of legislative reforms (Bill C-83) introduced in the reporting period.

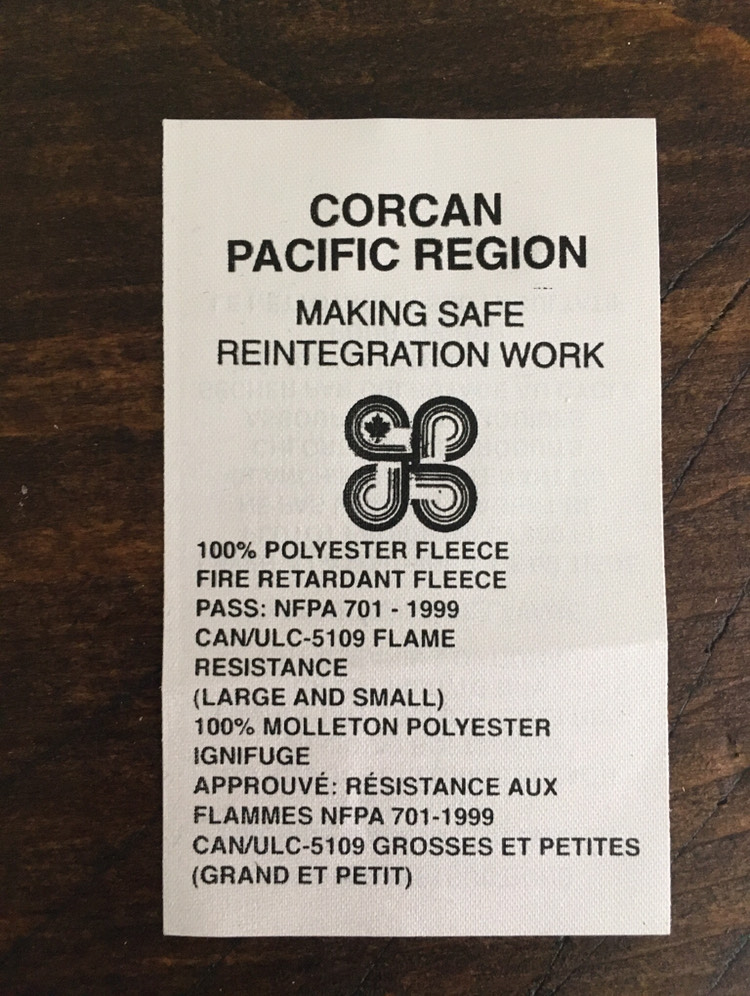

In terms of the national-level investigations featured in this year’s report, my Office has a long history of reporting on learning and vocational training behind bars and has made a dozen or so national-level recommendations in the past ten years. CSC has remained steadfast and impervious to expanding or updating inmate access to technology and information behind bars. Many prison shops require offenders to work on machines no longer used in the community. Few prison industries provide training or teach skills that are job-ready, or meet current labour market demands. Incentives to put in an “honest day’s work” are few and far between; many offenders told us that they perform mindless work, otherwise they would be locked up all day. The Service has continued to maintain and invest in obsolete industries and infrastructure and prisons have become such information depriving environments that these problems now appear unsolvable.

Since 2002, there has been a moratorium in place prohibiting offenders from bringing a personal computer into a federal institution. In 2011/12, CSC outright rejected the Office’s recommendation to lift this ban and this decision is still in effect today. The Service’s response to other recommendations to expand learning and skills acquisition, including opening up access to more Red Seal trades and apprenticeship programs, have generally focused on limited pilots; they have not been addressed in a substantive or sustained way. There has been little movement on recommendations designed to promote digital literacy behind bars – access to monitored email, tablets or supervised use of the Internet. Federal corrections in Canada is falling further behind the rest of the industrialized world and is failing to provide offenders with the skills, education and learning opportunities they need to return to the community and live productive, law-abiding lives.

Given the overall inertia and inaction in this area, I have elected not to make any additional recommendations to CSC arising from this investigation. Instead, I want to direct a summative recommendation to the Minister:

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety establish an independent expert working group to guide implementation of the Office’s current and past recommendations on education and vocational training in federal corrections. This work should include timelines and clear deliverables.

Prison sexual violence is an issue that has gone ignored for too long. As it stands, there are no public statistics, research or academic literature published in this area in Canada. As a result, the prevalence and dynamics of the problem in federal corrections are poorly understood. CSC does not publicly report on this problem, does not collect, record or track statistics and has never conducted research in this area. It is largely by virtue of this silence and organizational indifference that there are considerable gaps in the Service’s approach to detecting, tracking, responding to, investigating, and preventing sexual coercion and violence. At the very least, what we have confirmed in the course of this investigation is this: sexual violence is a systemic problem that exists in Canadian federal prisons. Furthermore, violence and victimization disproportionately affect those who are already the most vulnerable to maltreatment and negative correctional outcomes.

Sexual violence need not be seen or dismissed as an inevitable consequence of the incarceration experience, even if it is an issue that “runs below the radar” as one staff member told us. And an organizational culture that looks the other way is one that passively enables such destructive and predatory elements to thrive. In my report, I have offered some recommendations aimed at bringing this issue out of the shadows, and I implore federal corrections to take cues from countries who have implemented a bold, zero tolerance approach to eradicating sexual violence from their prison system. It is time for CSC to have an open and honest conversation about this problem and what can be done about it. Confronting these issues requires leadership not silence. As with other complex correctional dynamics, it is one that can be prevented through intentional, evidence-based interventions. These efforts will, however, require cultural and attitudinal shifts, among staff and inmates alike.

My assessment is that legislation is required to ensure this issue is properly addressed and given the profile and attention it deserves. Therefore, I make the following recommendation:

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety introduce, in the next year, a legislative package that endorses a zero tolerance approach to sexual violence in federal corrections and establishes a public reporting mechanism for preventing, tracking and responding to these incidents, similar to the Prison Rape Elimination Act in the United States.

In the meantime, CSC should put in place a proper, dedicated and robust policy and review framework that would anticipate and prepare for the introduction of legislated reforms in this area.

In closing, there can be no doubt that the COVID-19 situation threw a curve ball into all of our lives, not just workplans and corporate priorities. We finished out the reporting year (March 31, 2020) in the middle of a pandemic outbreak. Though visits by my Office to institutions were suspended mid-March, critical services were maintained. Clearly, however, it will be some time before things normalize, and no one can predict when my Office or CSC will resume to a business as usual footing. I want to commend my staff for how this crisis and the disruptions to normal workplace routines have been managed. There undoubtedly will be a time and place to consider the lessons learned from this experience, but I will save that for another, and hopefully, brighter day.

Ivan Zinger, JD., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

June 2020

Executive Director’s Message

I cannot express enough thanks to all OCI team members for their dedication and hard work in delivering our mandate with the highest degree of excellence and professionalism throughout the entire fiscal year, which ended under extraordinary circumstances. The end of the fiscal year was anything but business as usual.

The COVID-19 pandemic impacted OCI operations at their very core, resulting in the activation of our Business Continuity Plan in mid-March. As an essential service providing critical external prison oversight, around 90% of our staff had to work from home and we suspended all of our planned visits to penitentiaries. Nonetheless, our team members kept delivering on their core functions – taking inmate calls, investigating individual complaints, reviewing uses of force incidents – all the while taking stock of a new reality by monitoring inmates’ conditions of confinement in all federal penitentiaries on a regular basis. Of note, the Office was able the increase the number of complaints it addressed from last year.

At the time of writing this message, five out of 43 penitentiaries had outbreaks of COVID-19 infections among inmates, and only one known active case. As the CSC deployed an array of measures to prevent the introduction and spread of COVID-19 inside all of its institutions, our team was there to take the pulse. In April, our Office published a COVID-19 Status Update highlighting the impacts and challenges of this pandemic on federal penitentiaries, all the while demonstrating the need for the CSC to ensure compliance with both human rights and public health standards. In June, our Office issued a second COVID-19 update that focused on the prompt return to the “new normal.”

Beyond the COVID-19 situation, over the past fiscal year, the investigative team responded to 5,553 offender complaints, conducted 1,132 interviews with offenders, and staff spent a cumulative total of 354 days visiting federal penitentiaries across the country. The Office’s use of force and serious incident review teams conducted 1,109 use of force compliance’ reviews and 109 mandated reviews involving assaults, deaths, attempted suicides and selfharm incidents. On the research and policy side, the Office finalized three key national systemic investigations and included them in this year’s Annual Report, despite the impact of the pandemic on workload and priorities.

The Office has introduced new business practices to optimize linkages between individual investigations and systemic reviews/investigations. A few of the measures to achieve this goal include the co-location of the policy and research group with the investigative stream, regular coordination meeting between these two teams, and the introduction of the CI cases (i.e. Correctional Investigator cases), whereby the investigative stream identifies and brings to the CI’s attention individual cases that have potential systemic dimensions.

I share the Correctional Investigator’s vision for the office as a world-leading correctional ombudsman’s office, particularly in today’s digital economy. I picture an innovative, adaptive and flexible organization, confident in the face of rapid technological change. This year, the OCI made great strides in implementing new technologies to assist the Correctional Investigator in filling his assumed function. Some of these new technologies include: hosting the public web site using Cloud services, a shared case management system leveraging modern software and a collaboration platform to communicate internal information. As the pace of digital disruption is accelerating, the OCI developed a five-year IM/IT plan that takes the organization from one that is mostly paper-based system to one with a full digital office.

In the year ahead, the Office will build upon the great work already undertaken and modernize our business processes in an effort to improve investigations of offender complaints and systemic issues, in order to fulfill our legal mandate to its fullest.

Marie-France Kingsley

Executive Director

National Issues – Major Cases and Updates

Kent Institution

Introduction

This section summarizes policy issues or significant individual cases raised at the national level in 2019-20. Most of the issues and cases presented here were the subject of an exchange of correspondence or an agenda item on bilateral meetings involving the Commissioner and myself along with our respective senior management teams. These meetings have proved useful in bringing forward issues, exchanging perspectives and seeking earlier and less formal ways to resolve them. This section, then, serves to document progress in resolving issues of national significance or concern.

1. Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) – Case Reviews

In my 2018-19 Annual Report, I announced that the first medical assistance in dying (MAiD) procedure performed inside a federal correctional facility had occurred, and that my Office would carry out a review of this case. Footnote 1 There are three known cases of MAiD in federal corrections, two carried out in the community, and each raises fundamental questions around consent, choice, and dignity. In the two cases reviewed in the reporting period, my Office found a series of errors, omissions, inaccuracies, delays and misapplications of law and policy.

My investigation of the assisted death performed in a penitentiary turned on the question of whether there were more humane alternatives for managing this particular individual’s progression of terminal illness. To be clear, I have no doubt that the actual procedure, in this instance, was carried out professionally and with due consideration to the criteria laid out in Bill C-14. That was not the focus or concern of my review. Though I do not want to identify this individual, it is important to know that he was a non-violent recidivist serving the minimal (two-year) period allowable for a federal sentence. Even after parole was denied, I question how this particular individual’s risk could have been considered unmanageable in the community given his terminal illness. The decisions to deny parole and then provide MAiD in a prison setting seem out of step with the gravity, nature and length of this man’s sentence. With no other alternative available, the decision to deny full and day parole was almost certainly a factor in shaping his decision to seek MAiD. My review raised other questions about whether his case management team exercised due diligence or sufficient urgency in considering a suitable community placement, or what specifically prevented CSC from submitting a parole by exception (Section 121) compassionate release application to the Parole Board of Canada. Footnote 2

I shared these and other concerns with the Commissioner in early August 2019. In its response, CSC insisted that the decision to proceed with assisted death in the correctional facility was based on the explicit request of the inmate. It cited professional standards of practice to accept and respect the “wishes of competent patients.” It should be noted that, in this particular case, the individual expressed interest in “compassionate parole” within weeks of receiving news of his terminal illness, and several months before MAiD was administered. His parole application was submitted less than a month later, which was subsequently denied. Even still, case management records indicate that he expressed interest again for “compassionate leave” and submitted an application to appeal the Parole Board decision less than a few weeks before undergoing MAiD. Up until a few days before his death, there were high-level exchanges between CSC and the Parole Board to ensure that all avenues for release had been exhausted.

As I have discussed numerous times before, questions of autonomy and free choice in the context of incarceration are difficult to square. In this case, the “wishes of competent patients” must be seen in context of the seemingly inflexible system of sentence administration and lack of viable release alternatives for non-violent offenders, including medical parole. It would seem that this man “chose” MAiD not because that was his “wish,” but rather because every other option had been denied, extinguished or not even contemplated. This is a practical demonstration of how individual choice and autonomy, even consent, work in corrections.

The other case of MAiD investigated this past year revolves on the intersection of mental and physical illness and the capacity to provide informed and voluntary consent for assisted death. In that case, the inmate was suicidal and suffering from mental illness. He was terminally ill and a designated Dangerous Offender. He would threaten suicide if he was not provided MAiD. His prospects for release, even considering the advanced stages of his illness, were minimal.

Once again, these are circumstances that would never be confronted by free citizens in the community when choosing to end life. Hopelessness, despair, lack of choice and alternatives, conditions imposed by the fact and consequence of incarceration, are issues magnified in the correctional setting. As the Government considers extending MAiD beyond physical illness to intolerable psychic pain, there must be careful deliberation of the mental health profile of Canada’s prison population. For prisoners, matters of free choice are mediated through the exercise of coercive administrative state powers. There is simply no equivalency between seeking MAiD in the community and providing MAiD behind prison walls. Footnote 3

CSC’s response also stated that Health Services would strengthen its information sharing processes with the Parole Board to strengthen early release decision making. This would apply to all persons with a “designation of terminal illness and is not exclusive to those seeking [MAiD].” Further, CSC stated that it had implemented a communications strategy in June 2019 to “spread awareness of Section 121 of the [ Corrections and Conditional Release Act ].” These are necessary measures, but need to be considered in context of how rare and difficult it is to gain exceptional release from prison on compassionate or terminal illness grounds. Footnote 4

My review of these cases suggests that the decision to extend MAiD to federally sentenced individuals was made without adequate deliberation by the legislature. Though I understand and accept the Government’s decision to make assisted death available to those under federal custody, two aspects of how MAiD was legislated and later applied in the correctional context seem to make little sense from an accountability and public transparency point of view. The first is the decision to exempt CSC from reviewing or investigating MAiD deaths. This exemption is untenable given that CSC is, de-facto , the state agent that enables or facilitates assisted death to people under federal sentence. There just has to be some degree of internal scrutiny, transparency and accountability that goes with the exercise of such ultimate and extreme expressions of state power, even if MAiD is provided for compassionate reasons. By removing the legislative requirement for CSC to investigate, this measure also removes the obligation for the Service to provide notice “forthwith” of an inmate death involving MAiD to my Office. In effect, there is no legal or administrative mechanism for ensuring accountability or transparency for MAiD in federal corrections. Footnote 5 Surely, this exemption was an oversight that demands correction.

Secondly, that MAiD is allowed to be carried out in a penitentiary setting, under so-called “exceptional circumstances,” seems inconsistent with the legislation’s intent to provide Canadians with a legal option to end their life with dignity at a time and place of their choosing. It is simply not possible or desirable to provide or meet those intents in context of incarceration. As I have stated previously, the decision to seek MAiD is best made in the community, by parolees not inmates. Canada’s correctional authority should not be seen to be involved in enabling or facilitating any kind of death behind bars. It is simply incongruent with CSC’s obligation to protect and preserve life.

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety jointly with the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada strike an expert Committee to deliberate on the ethical and practical matters of providing MAiD in all places of detention, with the aim of proposing changes to existing policy and legislation. This deliberation should consider the issues brought to light by my Office, as well as the latest literature emerging from Canadian prison law and ethics. In the meantime, and until the Committee reports, I recommend an absolute moratorium on providing MAiD inside a federal penitentiary, regardless of circumstance.

2. Replacement of CSC’s Prisoner Escort Vehicles

In my 2016-17 Annual Report, I brought forward a series of safety, design and dignity concerns regarding CSC escort vehicles used for institutional transfers and to transport prisoners to attend court, temporary absences or outside medical appointments. At the time, I wrote about the claustrophobic experience I had in sitting scrunched in the back of one of these vehicles:

…the experience left me feeling as if personal safety and human dignity did not matter to the designers or operators of such vehicles. …Completely enclosed in metal, the compartment insert where shackled prisoners are kept is totally devoid of any comfort or safety feature, including seatbelts. These vehicles, which are essentially retrofitted and modified family minivans (e.g. Dodge Caravan), were never designed or crash-tested with a metal compartment of this size. Should there be an accident, as occurred in New Brunswick in 2013, individuals within the compartment would literally be thrown around inside, which could result in critical injury or even death.

In response, the Service committed to replacing its current fleet of escort vehicles to “reflect recent industry advancement in design and configuration.” It also agreed to review purpose built security escort vehicles currently in use by the RCMP.

OCI employee seated in the back of CSC’s prototype

security escort vehicle.

In September 2019, the Office was invited to view a prototype for the replacement of CSC’s security escort vehicles. The design of the prototype vehicle, like its predecessor, had similar disregard for health, safety, space, dignity or comfort of inmate passengers. Bench width, seat to ceiling height and overall cubic feet of space were not a demonstrable improvement on the previous claustrophobic design. The prototype had no seatbelts for inmate passengers, despite being supplied with these assemblies from the manufacturer. On the other hand, the prototype can accommodate up to five staff members in relative comfort and safety, raising the possibility that the design of the inmate insert may have been compromised to accommodate CSC policy requirements for security escorts. Footnote 6

CSC’s Security Branch cites three generalized concerns with equipping their escort vehicles with seatbelts:

- Concern over seatbelts becoming weapons and being used against staff/offenders in a violent way.

- Concern for staff safety in reaching inside the vehicle to unbuckle an offender.

- Concern in the event that an inmate harm him/herself with the buckle or the strap.

Compartment for inmate transport in CSC’s prototype

security escort vehicle.

When asked to provide specific incident data, cases or evidentiary information that demonstrates that seatbelts have ever been used in such violent manners, CSC has yet to produce any such documentation. When asked if CSC escort vehicles were equipped with seatbelts in the past, the Service was unable to answer. Impressionistic or anecdotal evidence should not be used as a substitute for fact.

When these and other concerns, including the fact that the Service failed to consult with inmates in the design or procurement stages, were brought forward to the Commissioner in late November 2019, she responded that she would personally inspect the prototype vehicle. Subsequent to this inspection, I understand that consideration is being given to additional features “to increase the space available for inmates and address concerns related to seatbelts, including the possibility of adding an extra bench.”

The protracted resistance and still apparently unresolved decision on the seatbelt issue reflects poorly on the Service. When CSC staff members were asked if they would allow a family member or loved one to ride in the back of one of these vehicles without seatbelt restraints, hand holds or other means to protect oneself the answer was decidedly no.

It does not need to be this way. With self-reflection, innovation in design and change in attitude, there is nothing that is irreconcilable with staff safety/security in equipping prisoner escort vehicles with seatbelts. Citing unfounded and uninformed security “concerns” should never be allowed to stand in the way of reason, professionalism or evidence. Finally, (though it should never have to come down to this), if CSC fails to equip these vehicles with seatbelts, it will be in violation of the Canada Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (CMVSS), specifically CRC c.1038. Footnote 7

- I recommend that the replacement fleet of CSC escort vehicles be equipped with appropriate safety equipment for inmate passengers, including hand holds and seatbelts, and that any prototype vehicle be inspected by Transport Canada authorities before being put into production and service.

3. Bill C-83 Reforms and Implementation

On June 21, 2019, Bill C-83 An Act to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act and Another Act , received Royal Assent. It promised to make “transformational changes” to the federal correctional system. The primary legislative intent was to abolish solitary confinement as defined by the Mandela Rules (confining inmates for 22 hours or more a day without “meaningful human contact”) by replacing the previous administrative segregation regime with Structured Intervention Units (SIUs). Implemented at the end of November 2019, there are SIUs at ten men’s institutions as well as all five regional women’s facilities.

Structured Intervention Units (SIUs)

Bill C-83 maintains the previous grounds for administrative segregation placements, namely when an inmate cannot be managed safely within a mainstream population. As with the former administrative segregation regime, the new legislation does not prohibit the placement of mentally ill people in SIUs, nor does it place hard caps on how long individuals can be kept in restrictive confinement environments. Due process consists primarily of a paper review by an external reviewer of material prepared and provided by CSC.

Section 32(1)(b) of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) stipulates that an inmate in a SIU must be provided an opportunity for “meaningful human contact.” Section 36(1) then provides for four hours of out-of-cell-time including:

…the opportunity to interact, for a minimum of two hours, with others, through activities including, but not limited to, a) programs, interventions and services that encourage the inmate to make progress towards the objectives of their correctional plan or that support the inmate’s reintegration into the mainstream inmate population, and b) leisure time.

A regular SIU cell at Edmonton Institution

(formerly a segregation cell).

An occupied cell in the SIU at Kent Institution

The SIU at Port-Cartier Institution

As implemented, my Office has observed that the policy and practice to replace segregation is now largely defined by “time out of cell.” The opportunity to interact includes interactions between inmates and staff. To get to the point of the matter, it is the quality not quantity of human contact that counts, as well as the forms through which humanity is mediated in a prison setting. Policy should articulate and define what the law prescribes. Failing to operationalize “meaningful human contact” means that staff are left with little guidance on their legislated obligations. Some practical examples might help to illustrate the point:

- Is it enough to use fencing fabric in lieu of solid physical barriers to facilitate “meaningful” contact with other inmates in adjacent SIU yards?

- Are non-contact visits considered “meaningful” human contact?

- When a self-injurious inmate is counselled through or communicates via a food slot, should these contacts be considered “meaningful”?

- Do video visits meet the interaction standard? What about watching TV alone, in a cell, or with others?

- Does the inmate’s perception of “meaningfulness” count, or does any out-of-cell contact facilitated by correctional staff meet the test?

Given that the term “meaningful” is subjective and open to debate and interpretation, I have suggested that CSC look elsewhere for inspiration. For example, the Essex body of international experts Footnote 8 has defined “meaningful human contact” in these terms:

Such interaction (meaningful human contact) requires the human contact to be face-to-face and direct (without physical barriers) and more than fleeting or incidental, enabling empathetic interpersonal communication. Contact must not be limited to those interactions determined by prison routines, the course of (criminal) investigations or medical necessity.

However the term is operationalized, more must be done to open up SIUs to non-correctional personnel – outside groups, associations and stakeholders – who have proven and established rapport and trust among inmates. Expanding the range and opportunity for meaningful human contact in a maximum security setting means going beyond the provision of CSC interventions (or singular engagements), in which staff cumulatively record an inmate’s time-out-of-cell, daily, on an Android phone app (a recently implemented measure). Inmates who find their way into these units are not likely to be overly responsive to CSC overtures to participate in correctional programs and interventions. As it stands, all the time-out-of-cell examples, including access to programs, interventions, educational, cultural, spiritual, and leisure opportunities contemplated in policy, are defined and determined by internal prison rules and institutional routines. It is not at all clear that inmates in these units will find these measures “meaningful” to them.

The SIU at Kent Institution

Clinical Independence and Professional Autonomy of Registered Health Care Personnel

Bill C-83 includes important new provisions to support the professional autonomy and the clinical independence of registered health care professionals, including their freedom to exercise, without undue influence, professional judgement in the care and treatment of patients. Providing a legislative foundation for these principles better aligns correctional health care practice with international standards, including Rule 27 (2) of the Mandela Rules : “Clinical decisions may only be taken by the responsible health-care professionals and may not be overruled or ignored by non-medical prison staff.”

In practice, however, certain aspects of both legislation and policy contravene these intentions. Consistent with Rule 33 of the Mandela Rules , the new legislated reforms include provisions that require registered health care professionals to advise the institutional head if they believe that the conditions of confinement in a SIU should be terminated or altered for physical or mental health reasons (CCRA, s. 37.2). Even so, the health care professional only has the power to recommend . The authority to accept or reject the advice of the registered health care professional resides with the Warden. The clinician’s recommendation is subject to several levels of administrative review, delay and quashing.

Full clinical independence and undivided loyalty to patients in a correctional setting is undoubtedly difficult to accomplish. Many correctional jurisdictions struggle to consistently meet these principles because of a “lack of awareness, persisting legal regulations, contradictory terms of employment for health professionals, or current health care governance structures.” Footnote 9 This is also the case for CSC. The fact of the matter is that CSC’s Health Services is not fully independent from CSC operations. At the very least, full clinical independence would require prison health care staff to be employed by the provincial health body or the national health authority.

Patient Advocates

Patient advocacy services were included as part of the menu of reforms enacted through Bill C-83. Footnote 10 Specifically, section 89.1 of the CCRA now requires the Service to provide access to “patient advocacy services to support inmates in relation to their health care matters; and to enable inmates … to understand the rights and responsibilities of inmates related to health care.” This is an important and necessary measure. CSC needs a Patient Advocate model to protect the rights of patients; help patients explore all available alternatives; and to ensure that they fully understand the implications of their decisions without compulsion. Further, I am of the opinion that patient advocates should be external and functionally independent of the CSC. Such a model would better support the legislative intent of C-83 and would be more aligned with the spirit of the Mandela Rules.

- I recommend that CSC review independent Patient Advocate models in place in Canada and internationally, develop a framework for federal corrections and report publicly on its intentions in 2020-21 with full implementation of an external Patient Advocate system in 2021-22.

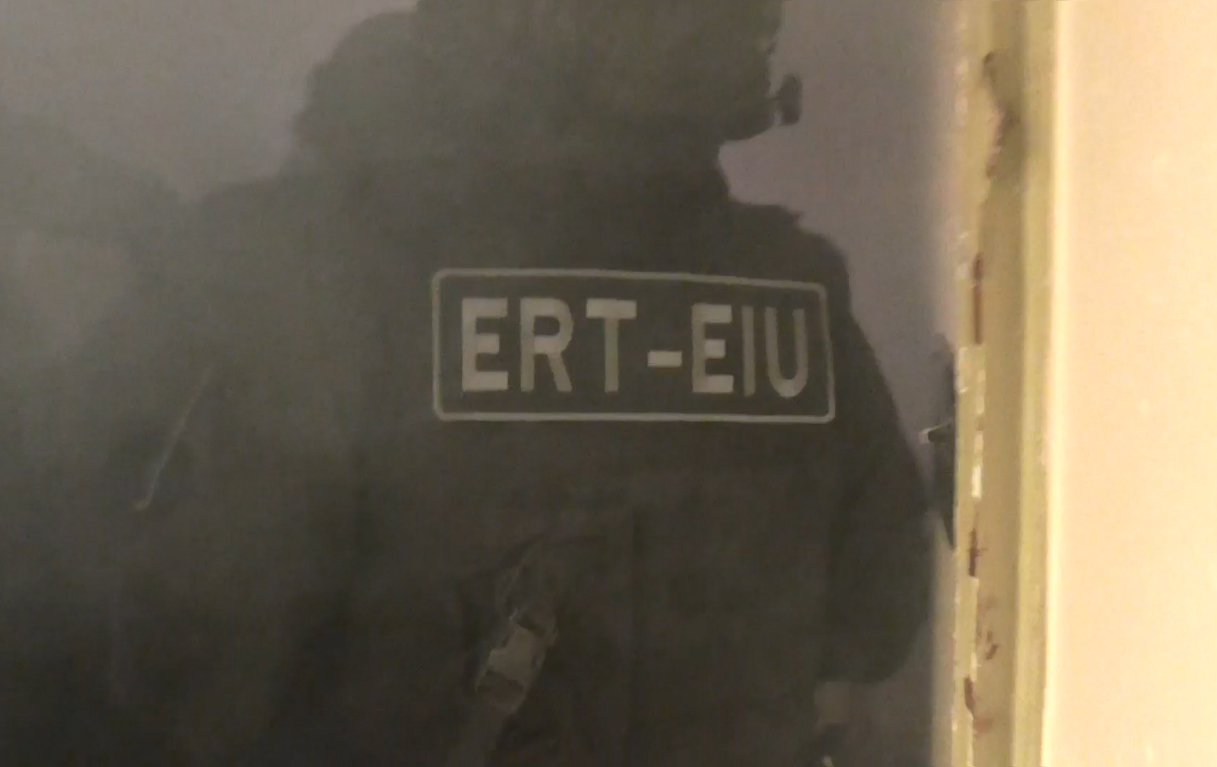

4. Use of Force Reviews – Egregious Cases

In the reporting period, the Office’s use of force review team identified a handful of egregious or inappropriate use of force interventions, two of which are captured below. These two cases illustrate the importance of my Office’s function in reviewing and overseeing use of force incidents in federal institutions. Though our external reviews are critical for transparency and accountability, this function is not, nor intended to be, a replacement for a robust and vigilant internal use of force review system.

Pain Compliance

In the first case, which involved Officers using a variety of pain compliance techniques to force an inmate to expel contraband (drugs) suspected of being secreted in his mouth, the facts are well-established because they are recorded on video. The inmate is escorted to an observation (dry) cell for a strip search. Refusing to show officers what may be under his tongue (suspected drug package), the inmate is restrained on the ground, already cuffed from behind. While lying naked on his stomach, and with several Officers present, a series of “pain compliance techniques” are applied – ankle torsions, pressure points on the nose and on the forehead, stepping (full weight) on the back of the inmates’ knees and on his ankles, rolling of baton on his ankles. On the Warden’s authorization, pressure points are also applied to the inmate’s jaw. Video evidence determines that various pain compliance techniques are used for 17 continuous minutes. None have the desired effect.

The inmate is eventually left alone in the dry cell where he later shows signs of a drug overdose. Narcan is administered and an ambulance called. He eventually provides the mostly empty package, which subsequently tests positive for heroin.

CSC officers restraining the inmate prior

to applying “Pain Compliance”

Contrary to the Engagement and Intervention Model , the officers and managers present do not appear to reassess the need, effectiveness or reasonableness of their interventions. Though the inmate had clearly stated and shown that he had no intention of handing over the secreted package, he did not display any other overt signs of violence or other resistive behaviours.

Despite obvious questions about the necessity or proportionality of force used in this case, the institutional (Level 1) review determined that the force used was appropriate, though some secondary concerns were raised about the pain compliance techniques applied (which are usually only used for a very short period of time in order to gain compliance or control of a person). Once restrained and unable to resist, these measures usually cease. According to policy, no further regional or national reviews were warranted, despite the continuous and intentional infliction of pain on a restrained inmate.

Upon receipt and review of the incident, the Office requested a regional review, which subsequently confirmed the initial institutional review that the intervention was indeed compliant with policy. Not satisfied with this response, I elevated this incident to the national level. After raising it with the Commissioner, she committed to reviewing the incident with members of her senior executive team. The police were contacted and the Region convened a formal investigation into this incident.

Subsequent to these measures, a CSC Security Bulletin was issued on March 26, 2020. It is entitled, Inmates who have Secreted Contraband in their Mouth – Response Options . The Bulletin is very detailed and includes this very explicit warning, in bold lettering, so as not to be missed:

There are no approved force options for removing an item from an inmate’s mouth or body cavity.

CSC officers applying “pain compliance” tactics.

To the extent that these corrective and remedial measures address the specific issues of non-compliance in question I am satisfied. I am less satisfied that this case, including review by CSC’s most senior executive members, did not prompt a more reflective consideration of concerns and questions that this incident raises beyond possible or different response options:

- How could an incident of this seriousness be considered a Level 1 use of force, and therefore not required to be reviewed at regional or national levels? Are there other serious use of force incidents that fail to make their way up the chain of command? If so, how many?

- Would the various pain compliance techniques used in the course of this incident, including their extended length, be considered excessive or otherwise contrary to any lawful purpose, regardless of context or setting?

- What are the powers, limits or thresholds to the “preservation of life” or “preservation of evidence” defences that could possibly justify the use of pain compliance in a correctional setting?

- Whether the eventual outcome of this incident could have reasonably been foreseen (overdose), which might obviate the need to use or apply extreme force in the first place?

The Security Bulletin effectively reduces the complexity of the scenario it is based on to a technical matter – it merely provides guidance on various response options that could/should be used to manage inmates who have secreted suspected contraband in their mouth. It is mostly silent on pain compliance; specifically, throat holds or application of pressure points to the jaw, or, for that matter, whether other techniques used in this incident (ankle torsions, standing on the back of an inmate’s legs) are appropriate, safe and authorized for use in CSC facilities. The Bulletin avoids the more difficult and controversial questions regarding the extent or types of pain compliance that can be legitimately used in federal corrections, for what purpose(s) and for how long. It simply cannot be assumed or taken for granted that staff know or have the answers to these matters.

Use of Stun Grenade

The second case involves the use of a stun grenade Footnote 11 detonated inside an inmate’s cell following deployment of several grams of an irritant agent (pepper spray). In this case, the inmate had barricaded himself in his cell, he had shown threatening/aggressive behaviour towards staff, he was actively resistive, and responding officers could not get a visual and large quantities of pepper spray had already proven ineffective to gain compliance. The particular circumstances of this case justified an intervention. Officers were called to do a cell extraction. These facts are not in dispute.

|  |

|  |

Series of photos showing the fire caused by flash grenade detonated in the cell, and subsequent cell extraction.

The concern I have in this case is the decision to use a weapon of this explosive nature in the small confined space of a prison cell. This type of device should only be used in open areas: it is a defensive weapon that is used for crowd control. The manufacturer’s manual specifies that it should not be used in a space where the device can detonate less than five feet from an individual (which is obviously the case in a cell) as it poses documented risks. The detonation of a flash bomb in a cell is unsafe and inherently dangerous; in fact, the grenade started a fire in the inmate’s cell, possibly ignited by the flash or intensified by the previous deployment of pepper spray. Responding officers did not have a fire extinguisher on hand when they deployed the device. They also chose to restrain the inmate in his cell before putting out the fire.

On the facts of the case, it was evident that I would issue a recommendation to prohibit the use of stun grenades in confined areas such as cells. Which is what I did. That was the obvious thing to do. Unfortunately, the response I received is far from clear; in fact, it is downright puzzling. It infers that CSC has not endorsed or accepted my recommendation, in all its simplicity. Instead, the Service intends to contact the manufacturer to query why this particular “distraction device” should not be used in an enclosed space. CSC reviewers also want to find out what caused the fire in the cell – the device’s ignitor or the particular brand, combination or concentration of the pepper spray?

With due respect, these points are irrelevant. They only serve to obstruct and detract from the issue at hand. A stun grenade is not a “distraction device,” and should not be used in small enclosed spaces because it is inherently unsafe and dangerous. Full stop. My recommendation stands.

- I recommend that CSC issue immediate instruction prohibiting the use of stun grenades in closed or confined spaces, including cells.

5. Dry Cells

A “dry cell” toilet.

Under section 51 of the CCRA , a Warden may authorize, in writing, use of a ‘dry cell’ (a specially equipped direct observation cell and facilities used to search for and retrieve suspected contraband from bodily waste) based on reasonable grounds to believe that an inmate has ingested or is concealing contraband in a body cavity. The Office investigated a case in which an inmate spent nine consecutive days in a dry cell. No drugs or any other contraband were found.

The conditions of dry cell confinement are, by far, the most degrading, austere and restrictive imaginable in federal corrections. The dry cell procedure requires strip-searching, around the clock direct observation and 24/7 illumination of the cell. Dry-celling imposes restrictions on any and all activity that would compromise the recovery of suspected contraband. The demands of staff are equally dignity depriving. Staff are required to observe and document the entire time that an inmate is on the toilet, write search and observation reports for every bowel movement, don protective equipment, search for contraband and hand over any seized item to a Security Intelligence Officer. It’s an extraordinary procedure.

Much needed legal and national procedural safeguards for dry celling have been put in place since the Office first publicly raised this issue in its 2011-12 Annual Report. Some of these safeguards include:

- Requirement to give written notice for reasons of placement.

- Inmates are given the opportunity to retain and instruct legal counsel without delay.

- Requirement to give notification to Health Services.

- Daily review of placements by the Warden, including opportunity for an inmate to make written representations for consideration at the daily review.

Notwithstanding, CSC has resisted placing any upper limit on how long a person can be held in a dry cell with no plumbing. In my opinion, beyond 72 hours there can be no further reason or justification to detain or keep a person in such depriving conditions. Staffing an observation post beyond that time seems equally pointless. After three days, surely this procedure becomes unreasonable, if not strictly punitive.

In this case, I was compelled to reissue a recommendation made by the Office nearly a decade ago, but to this day still has not been accepted or actioned:

- I recommend that dry cell placements exceeding 72 hours be explicitly prohibited in federal corrections.

6. Inmate Access to the Media

Through the reporting period the Office intervened in cases or complaints that involved inmate access to the media. In one case, we found that some of the policy criteria set out in Commissioner’s Directive 022 – Media Relations to be unreasonable, irrelevant or not founded in law. In unreasonably denying or delaying an inmate’s access to the media, the Service may be in violation of recognized democratic principles and constitutionally guaranteed rights. An incarcerated person does not forfeit the right to freedom of expression, and the wider public has a right to be informed of what goes on behind prison walls.

Restrictions on media access to prisoners, which in this case turned on unreasonable delays in approving media access to conduct an inmate interview during Fall 2019 National election period, must not unduly impede or infringe upon fundamental rights and democratic values. The well-recognized “caretaker” principle may apply to government bodies and employees, including CSC, during an election period, but there is no legal basis to muzzle, deny or justify restricting citizen access to the media, including those deprived of liberty.

In the course of our investigation, we found that CD-022 does not cite or refer to any of these legal, democratic or constitutionally protected rights and principles, which should be the touchstones for policy instruction in this area of corrections. The potential influence that a media interview could have on “how [inmates] conduct themselves and demonstrate respect for others” are an overreach of law, and cannot reasonably be considered relevant; in fact, it could be considered censorship. In a free and democratic society, behavioural expectations have no place in governing anyone’s access to the media.

This is not to suggest that journalists have an immediate, unfettered or total access to interview inmates at any time. For instance, I accept that there are legitimate security reasons and operational constraints (especially for on-site camera interviews) that need to be considered, but these must be grounded in law, not how CSC thinks or expects an inmate to behave or out of concern with what s/he might say to the media.

In bringing this case forward, the Service agreed to review CD-022 and address the concerns noted above. Specifically, the Commissioner committed that the revised policy on media relations will acknowledge inmates’ right to freedom of expression, in accordance with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms . It will also reaffirm that media interviews may proceed so long as they do not jeopardize the safety and security of the institution, other inmates, or any person. I was satisfied with this response and await promulgation of the revised Commissioner’s Directive.

CCTV capture showing inmates throwing food at protected

status inmates – Edmonton Institution

CCTV capture of CSC staff walking ahead of the inmates who

were later assaulted – Edmonton Institution

Institution

7. Edmonton Institution Update – Staff Discipline

On January 9, 2020, the Office requested all staff disciplinary investigations and measures related to the events involving repeated assaults on protective custody inmates that occurred at Edmonton Institution between August 1, 2018 and October 25, 2018. Footnote 12 This was a follow-up accountability measure arising from my investigation into these matters. The Office received and reviewed a total of ten staff disciplinary reports, as well as the Disciplinary Investigation Report into Allegations of Negligence in the Performance of Duties during the Period of August 2018 to November 16, 2018 (dated February 4, 2019).

Of the ten CSC staff members investigated, six were subject to disciplinary measures, including financial reprimands and verbal/written reprimands. These reprimands primarily resulted from neglect of duty, failure to take appropriate action to ensure the safety and security of inmates and failure to appropriately document and report the incident. No one of a senior rank received a reprimand of any kind.

8. Indigenous Corrections – Update

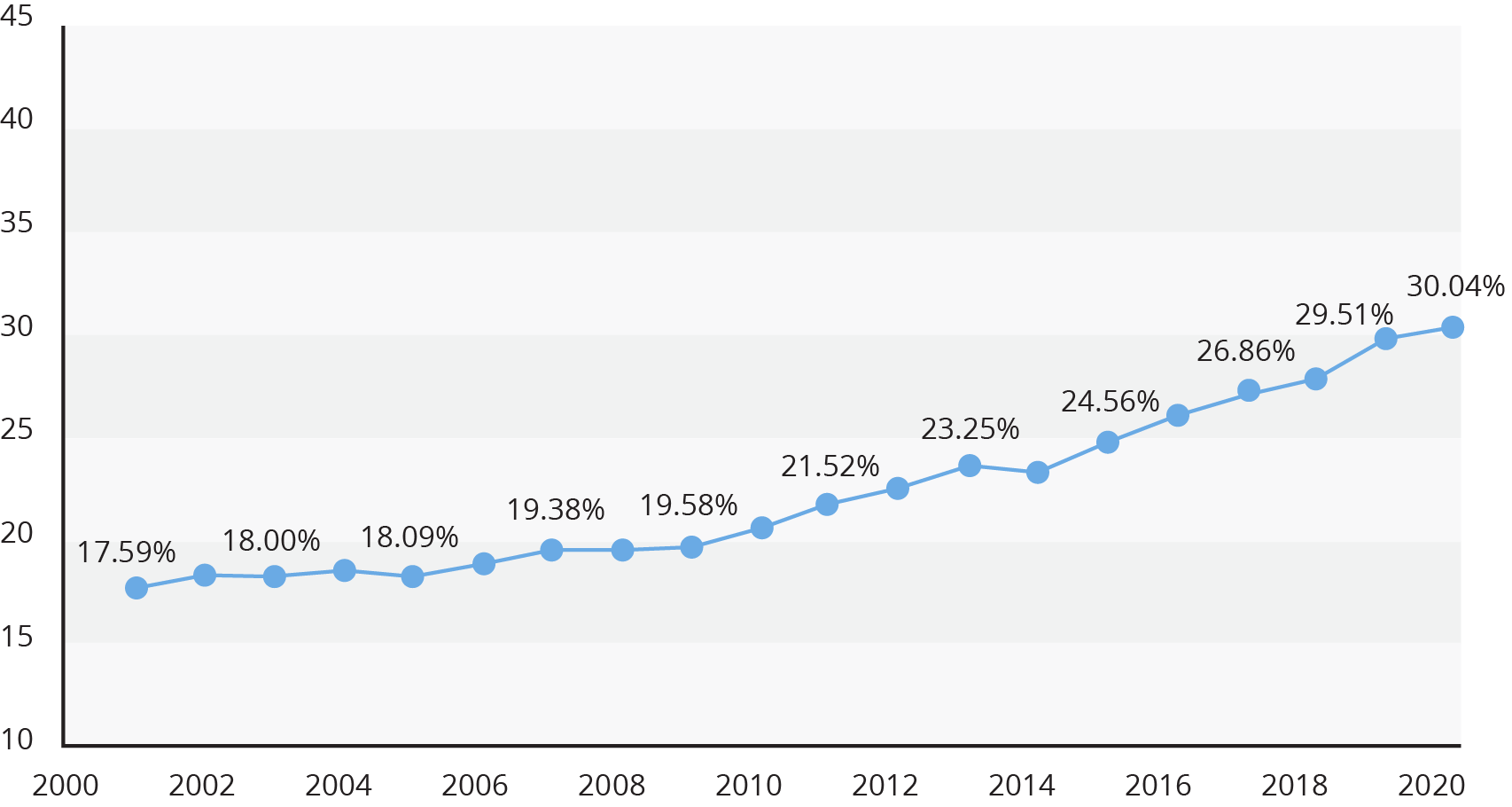

In January 2020, I issued a press release and statement to record the fact that Indigenous over-representation in federal custody had reached a new historic high, surpassing the 30% mark. Footnote 13 While accounting for 5% of the general Canadian population, the number of federally sentenced Indigenous people has been steadily increasing for decades. More recently, custody rates for Indigenous people have accelerated, despite declines in the overall inmate population. As I indicated, these disturbing and entrenched imbalances represent a deepening “Indigenization” of the federal inmate population.

The graph demonstrates an overall and relatively

consistent increase in the federally incarcerated

Indigenous population since 2001.

I recognize that many of the causes of Indigenous over-representation reside in factors beyond the criminal justice system. However, when I issued the statement, I noted that consistently poorer correctional outcomes for Indigenous offenders (e.g. more likely to be placed or classified as maximum security, more likely to be involved in use of force and self-injury incidents, less likely to be granted conditional release) suggests that federal corrections makes its own contribution to the problem of over-representation. For example, a recent national recidivism study shows that Indigenous people reoffend or are returned to custody at much higher levels, as high as 65% for Indigenous men in the Prairie region within five years of release. A higher rate of readmission to custody (revocations or reoffending) suggests shortcomings in the system’s capacity to prepare and assist Indigenous offenders to live a law-abiding life after release from custody.

In the coming year, my Office will be launching a series of in-depth investigations examining a selection of programs and services in CSC’s Indigenous Continuum of Care. We want to hear from Indigenous inmates to learn from their experiences. We intend to look at program participation criteria and compare results and outcomes for those who are enrolled in Indigenous-specific interventions. The Office’s review of Indigenous Corrections will also include a deeper probe of the over-involvement of Indigenous offenders in use of force incidents including comparative data and findings on the causes, frequency, type and severity of force used. Preliminary and previous work in this area (e.g. An Investigation of the Treatment and Management of Chronic Self-Injury among Federally Sentenced Women , September 2013) suggests that specific attention needs to be paid to the circumstances and social histories of Indigenous women, particularly those who present with serious mental health issues, as they appear to be vastly over-represented in use of force incidents among federally sentenced women.

National Investigations

1. A Culture of Silence: National Investigation into Sexual Coercion and Violence in Federal Corrections

Introduction

Sexual coercion and violence (SCV) is an issue that has notoriously existed in the shadows of society, and is among the most under-reported types of crimes. For example, among the general Canadian population, it has been estimated that only approximately 5% of all sexual assaults are reported to police. Footnote 14 Prison settings are by no means an exception to this reality. By their very nature, prisons are largely closed to public view. And it is in part due to this environment of secrecy that sexual violence in custodial settings is even less understood and even more susceptible to underreporting than in the community.

Much like any individual who has experienced sexual victimization, incarcerated individuals face a myriad of disincentives for reporting experiences of sexual violence. Many are afraid to report, fearing retaliation, retribution or re-victimization by the perpetrators, be it other inmates or staff. Furthermore, they face the risk of not being believed, being ridiculed, or even punished for reporting coerced sex. As has been observed in the wider community, most complaints of sexual violence that occur behind bars never reach the courts.

WHAT IS SEXUAL COERCION AND VIOLENCE?

It is any non-consensual act of a sexual nature, including pressure, and/or threats of such acts done by one person or a group of persons to another.

It can range from unwanted sexual touching, kissing, or fondling to forced sexual intercourse. Sexual assault can involve the use of physical force, intimidation, coercion, or the abuse of a position of trust or authority.

It includes any sexual act or act targeting a person’s sexuality, gender identity or gender expression, whether the act is physical or psychological in nature that is committed, threatened or attempted against a person without the person’s consent. It includes sexual assault, sexual harassment, stalking, indecent exposure, voyeurism and sexual exploitation. Footnote 15

It has been well established that institutional culture and leadership are key determining factors in creating environments that either prevent or permit sexual victimization. As the U.S. National Prison Rape Commission has recognised, prison-based sexual violence is not an intractable problem. The American experience attests that sexual violence behind bars is largely the result of correctional maladministration, deficient policies, negligence and unsafe practices. Prison rape becomes endemic however, when correctional officials fail to take the problem seriously, when they do not institute proper detection, enforcement and preventive measures. In light of these realities, criminal justice agencies have the unique responsibility to ensure that there are mechanisms in place to prevent, track, and respond to incidents of sexual violence.

WHO IS MOST AT RISK?

We know from international research that some of the most marginalized inmates are often the most vulnerable to sexual violence behind bars. These populations include the following:

Individuals with a history of trauma and abuse;

Individuals who identify as, or are perceived to be, lesbian gay, bisexual or transgender;

Young and juvenile individuals are at heightened risk;

Women are more at risk of sexual victimization; and,

Individuals who have a physical disability, mental illness, or cognitive/developmental issues.

For example, survey research on sexual victimization in U.S. prisons found that while 4% of prisoners overall reported having experienced sexual abuse in prison, the proportions were much higher for the most vulnerable populations. For example, the following groups reported experiencing SCV within the year prior to the survey:

6.3% of inmates with serious psychological distress.

12.2% of non-heterosexual inmates.

21% of non-heterosexual inmates with serious psychological distress.

Sexual Coercion and Violence in Canadian Prisons

The issue of sexual violence in prison is rarely raised in Canadian public discourse. And while it is a problem most associated with American prisons, we know that sexual coercion and violence occurs in custodial settings in Canada. The extent of the problem in Canada however is largely unknown. There are currently no reviews, studies, reports or academic literature examining the scope of this issue in Canada.

At present, Canada does not have an equivalent to the United States’ Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), nor are there any mandatory public reporting requirements in place to respond to sexual abuse and violence behind bars in Canada. While there is a complex array of policy, administrative and legal measures to address these issues, there is no overall strategy that specifically and intentionally aims to prevent sexual violence in Canadian federal penitentiaries. For this and other reasons, the extent or prevalence of the problem in Canadian federal corrections is simply not known.

That said, we know that a considerable portion of the Canadian inmate population self-reports engaging in sexual activity while incarcerated. For example, a 2007 National Inmate Survey conducted by the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) reported that 17% of incarcerated males and 31% of women self-reported engaging in sexual activity while in prison. Footnote 18 Unlike surveys conducted by the U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Canadian inmate surveys have not focused on whether or not sexual acts among inmates were consensual or coerced.

In November of 2018, The Edmonton Journal published an article on sexual assault in Canadian prisons. Footnote 19 Their findings suggested that both federal and provincial correctional systems alike have fallen disappointingly short in their methods of tracking incidents of sexual assault involving incarcerated individuals. It appears that while some provincial jurisdictions suffer from disjointed information systems and inconsistent record keeping (some jurisdictions only track cases of sexual assault where charges were officially laid), others simply do not appear to track allegations of sexual assault at all.

As for the federal correctional system, the situation does not appear to be much better. According to the same article, between 2013 and 2018, CSC was able to identify a total of 48 formal allegations of sexual assault from federal inmates (17 of these were from 2017-18 alone). While this is not an insignificant number on its own, the actual number of inmates who would have experienced SCV during this time is undoubtedly much higher.

At present, there is no way to accurately and systematically identify the number of incidents of sexual coercion and violence involving incarcerated persons, and there is no credible data or research that indicates the scope of the problem of sexual victimization in Canadian penitentiaries. Without proper reporting mechanisms, record keeping, and research, CSC runs the risk of using this absence of evidence as evidence of the absence of a problem. Turning a blind eye to this issue or looking the other way when it happens only serves to reinforce a culture of silence and indifference.

PRISON RAPE ELIMINATION ACT (PREA)

After decades of pressure from advocates and survivors, in 2003, the United States congress passed the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA), the intentions of which were to “provide for the analysis of the incidence and effects of prison rape in Federal, State, and local institutions and to provide information, resources, recommendations and funding to protect individuals from prison rape.”

The purpose of PREA was to develop national standards on the prevention of sexual assault in custodial settings. Furthermore, this law called for the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) to conduct regular anonymous surveys of inmates regarding sexual assault. It resulted in the creation of such bodies as the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission , responsible for developing standards for the elimination of prison rape, as well as the National PREA Resource Centre that provides training and technical assistance to those working in the corrections field.

In 2012, the U.S. Department of Justice issued the National Standards to Prevent, Detect, and Respond to Prison Rape . Further to these standards, correctional institutions are required to educate both staff and inmates on sexual victimization, investigate all allegations of sexual assault, track all incident information in the Survey of Sexual Victimization and disclose information to all relevant authorities.

This law has prompted numerous national studies on prison sexual assault in the U.S., advancing knowledge and practice on:

estimating the prevalence of sexual violence in prison settings;

understanding and changing the dynamics of sexual abuse in prison settings;

identifying victim and perpetrator profiles/characteristics;

regularizing the reporting of incidents and investigations of sexual assault; and,

developing training and prevention initiatives in custodial environments.

Context and Purpose

Addressing sexual violence in prison is as much an issue of upholding long-standing rules of safety and law, as it is one of advancing human rights in the current cultural climate. In many ways, Canadian corrections currently finds itself where the United States was prior to enacting PREA legislation – with an abundance of anecdotal evidence of individual experiences of sexual abuse in the prison system, but very little concrete data to demonstrate the dynamics of (and identify possible solutions to) what many knew to be a systemic issue.

Now more than ever, particularly in the context of social movements such as #MeToo and #TimesUp, Canada is behind when it comes to addressing sexual violence behind bars. This Office is breaking new ground by taking the first ever systemic look at the long-ignored issue of sexual coercion and violence in Canadian federal prisons. The Office’s intentions through this investigation are to:

- examine policies and practices currently in place in federal corrections in Canada for detecting, tracking, responding to, and preventing SCV in federal penitentiaries;

- identify gaps and opportunities for improvement to relevant policy and practice;

- highlight promising approaches that could serve to advance policy and practices aimed at responding to and preventing prison sexual violence;

- offer evidence-based recommendations to support progress in this area; and,

- importantly, give voice to the individuals and survivors of sexual violence in prison, who too often go unheard.

Methodology

The methods for the present investigation consisted of three main components:

- Examination of CSC Policies, Procedures & Research on SCV

- Analysis of CSC Official Incident Reports and Investigations of SCV Involving Incarcerated Individuals

- Incident Reports: All Incident Reports in CSC’s Offender Management System (OMS) that were created further to the official reporting of an alleged incident of SCV involving a federally-incarcerated person Footnote 23 ; and,

- Board of Investigation Reports (BoI): All CSC incidents for which a BoI was convened for incidents identified as involving SCV and federally-incarcerated persons. Footnote 24 These internal investigations, convened or conducted at the local (institutional) or national levels, represent a subset of all incidents, likely those deemed to be more severe in nature or consequence.

- Interviews with CSC Staff and Federally-Incarcerated Persons

- Staff Interviews: A variety of CSC staff were selected for interview based on their identified role in policy as part of the chain of responsibility when incidents of SCV arise (e.g., Chiefs of Health Care, security and operations staff, correctional managers). Where possible, staff who hold positions of trust with the inmate population (e.g., Chaplains, Elders), were also sought for an interview.

- Inmate Interviews: There are many practical and ethical challenges with attempting to solicit interviews with victims and perpetrators of SCV. In an effort to mitigate the potential risks associated with interviewing individuals who may have experienced SCV (directly or indirectly), voluntary interviews with representatives of the incarcerated population were conducted. Specifically, individuals holding positions such as Inmate Welfare Committee Chairs and representatives, Peer Counselors/Advocates, Peer Health Ambassadors, and Unit/House Representatives were invited to discuss the dynamics of SCV in CSC institutions.

Findings: Examination of CSC Policies, Procedures & Research on SCV

As with any type of criminal activity, when an incident of sexual assault is reported to CSC staff, it should immediately trigger procedures for reporting, investigating, and addressing the needs of those involved in the incident. Depending on the type, severity, frequency, and/or implications of the incident, outside agencies (e.g., police) may become involved and the incident may be subject to a Board of Investigation (BoI) led by the Incident and Investigations Branch at CSC’s national headquarters.

At present, CSC does not have a separate or specific Commissioner’s Directive (CD) or policy suite specifically detailing how CSC staff are expected to respond when a sexual assault is reported (or suspected to have taken place) in a federal institution. CSC policies and procedures for how to respond to alleged incidents of SCV are subsumed within directives and guidelines for general health emergencies, security incidents, and violations of the law by inmates.

Currently, there are only two sources of information that provide guidance to CSC staff on how to respond specifically when a sexual assault is reported by an inmate:

- What to Do if an Inmate is Sexually Assaulted is a single page on CSC’s internal website in the Health Services section. It provides basic information, with a focus on reporting procedures and the collection of evidence for investigative purposes.

- Sexually Transmitted Infections Guidelines – Appendix 7: Response to Alleged Sexual Assault is an appended document, directed almost exclusively at Health Services staff. This document is three pages in length, providing basic information on how nursing staff should collect and preserve physical evidence, offer nursing interventions to inmates, and report the incident to the internal authorities. It is the Office’s understanding that these Guidelines are currently under revision; however, their status or when they will be promulgated is unknown. Footnote 25

It appears from a review of the above documentation that the Health Services sector is mostly responsible for managing incidents of sexual assault. However, given the uniquely complex criminal nature of these incidents, expedient and effective coordination with various CSC sectors (e.g., health, security and correctional management) and outside agencies (e.g., police, RCMP) would be required to appropriately respond to and investigate these incidents. Taking into account the brevity and lack of clarity of policy instruction on how staff should respond to these incidents, this Office’s main concerns are as follows:

- The inaccessibility of the current guidelines/documentation. The guidelines that exist are buried in the seventh appendix of CSC’s guidelines on sexually transmitted infections. The placement of these guidelines makes them less accessible to staff, thus less likely to be used by staff.

- The shallow nature of the current guidelines. They lack detail, clarity on the roles and responsibilities of all staff in terms of timelines, the types of services that should be offered and timelines for these services (particularly for mental health). Furthermore, there are no clear guidelines on what should be done to keep victims (and perpetrators) safe once an allegation of sexual assault is reported.

- There is no mention of the procedures that should be followed when staff are implicated in allegations of sexual assault, aside from a brief mention in CD-060 Code of Discipline which indicates that institutional heads must notify local police, without delay, if staff are implicated in incidents or allegations of misconduct that constitute a criminal offence.

Taken together, of greatest concern to this Office is the absence of a dedicated and comprehensive policy suite for sexual coercion and violence involving federally-sentenced individuals.

- I recommend that the Service develop a separate and specific Commissioner’s Directive for incidents of sexual coercion and violence involving federal inmates, that describes in detail how all staff should respond when allegations of a sexual assault are made, or an incident is suspected of having occurred. This policy suite should also detail mechanisms for detecting, tracking, reporting, investigating and preventing such incidents. CSC should look to other jurisdictions who have developed comprehensive approaches to policy and practice (e.g., Prison Rape Elimination Act ) as it relates to sexual assaults involving incarcerated persons.

NATIONAL INMATE SURVEY ON SEXUAL COERCION & VIOLENCE IN CSC INSTITUTIONS

Through the course of this investigation, the Office learned that while CSC has conducted numerous national inmate surveys on various topics in the past, including the sexual activity of inmates, it has never conducted research on sexual violence in prison. It is in large part for this reason that the extent and prevalence of sexual coercion and violence in federal prisons in Canada is currently unknown.

Last year, the Office became aware that CSC was in the process of developing a national health survey of federal inmates, including a section on sexual health. In October 2019, through correspondence with CSC Health Services at National Headquarters, the Office learned that the draft survey instrument included a question on sexual assault. Specifically, the question read as follows:

In context of the investigation underway, the Office offered advice and comments to CSC on how to revise the existing question (e.g., include a longer time period than 6 months) and suggested the addition of other questions about sexual coercion in an effort to improve the quality and accuracy of the survey, as well as attempt to estimate the prevalence of sexual coercion and violence.

After numerous attempts to obtain a complete draft of the survey, on January 31, 2020, at the direction of the Commissioner, the Office was finally provided a copy. Upon review of the survey, it was apparent that not only were new questions not added, but that CSC removed the only question pertaining to sexual coercion and violence from the survey.

Given the clear need to gain a better understanding of the scope and nature of sexual coercion and violence in federal prisons, coupled with the Service’s demonstrable failure and unwillingness to conduct such work:

- I recommend the Minister of Public Safety directs that CSC designate funds for a national prevalence study of sexual coercion and violence involving inmates in federal corrections. The survey should be developed, conducted, and the results publicly reported on, by external, fully independent experts, with the experience and capacity to conduct research on this topic in a correctional setting.

Findings: Analysis of CSC Official Incident Reports and Boards of Investigation (BoI) Reports of SCV Involving Incarcerated Individuals

In accordance with CSC policy, in the event of an incident (such as an alleged sexual assault), staff are required to record and report incident details in documents such as Statement/Observation Reports, which are in turn used to inform Incident Reports that are created and filed in CSC’s OMS. Incident Reports are usually completed by institutional heads, and can be used as background information in the event a BoI is convened further to the incident in question. Footnote 26

Depending on the severity, possible consequences, frequency and type of incident, the reporting of incidents can result in a formal BoI (at the national or local level) by CSC’s Incident and Investigations Branch (IIB). Footnote 27 According to CSC, the purpose of a BoI is to assess and report on the circumstance surrounding the incident; provide information to CSC in order to prevent similar incidents; learn and share best practices; and, issue findings and recommendations. Footnote 28 For incidents where the behaviour of staff is under investigation, a disciplinary investigation and possible sanctions are determined by a separate CSC authority, and are subject to the Complaints and Grievance process.

In the absence of national prevalence data, or any specific data sources that track incidents of sexual coercion and violence, for the present investigation, all Incident Reports and BoI Reports from five years of incidents of sexual violence involving an inmate were included. Our search yielded a total of 72 unique incidents of sexual coercion and violence that were officially reported or investigated by CSC from April 2014 to 2019. Footnote 29 The following section is a summary of the findings from the analysis of CSC Incident (OMS) report data and Investigation (BoI) reports.

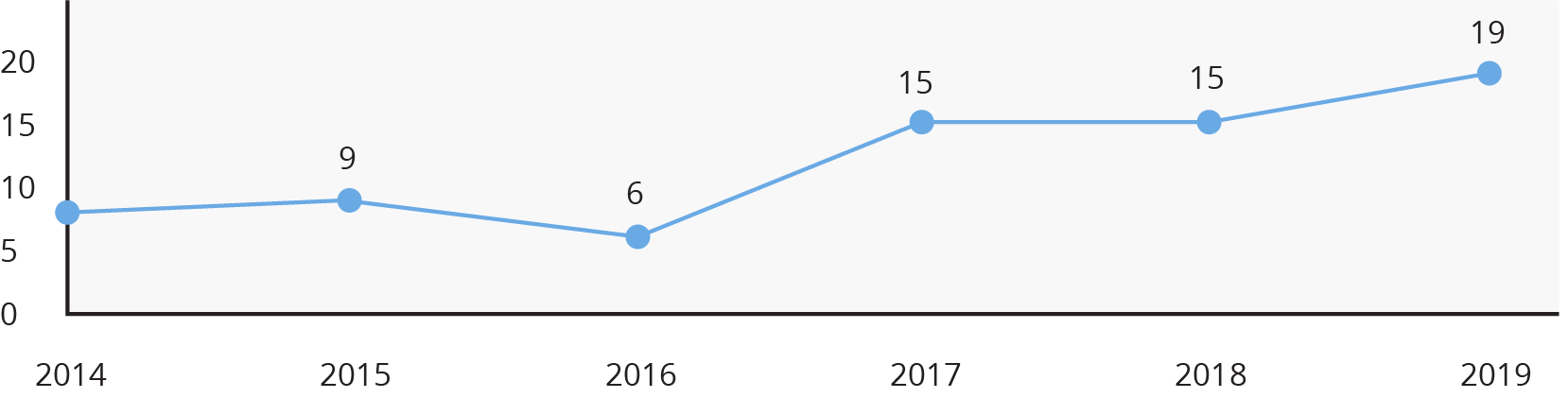

Number of Officially Reported SCV Incidents from 2014 to 2019

The graph demonstrates an increase in officially reported SCV incidents since 2014.

A. Incident Reports

From April 2014 to 2019, there was a total of 67 Incident Reports of sexual assaults involving a federal inmate. Over time, the number of reported incidents has been increasing, with nearly 30% of all cases having occurred in 2019.

Where did Most Reported Incidents of SCV Take Place?

There was a total of 22 different institutions that had at least one allegation of sexual assault involving an inmate during the period under investigation. Based on the Incident Reports, we were able to identify which institutions had the most reported cases. The top three institution were: 1) Warkworth Institution; 2) Bath Institution; and, 3) Fraser Valley Institution. Footnote 30 Overall, incidents were mostly reported from medium security (42%) or multi-level security (39%) institutions. Only eight incidents were reported from maximum security institutions. This could be attributable to a variety of reasons. It is possible that maximum security settings have a lower incidence of this type of offence as a consequence of greater restriction on inmate movement in these facilities. It could also, or instead, be due to a lower frequency of reporting of these types of incidents in maximum security settings. For example, these inmates may be less likely to report sexual assault given the greater (actual or perceived) risks and disincentives associated with reporting in this context, compared to lower security institutional settings; if this is the case, these results are demonstrative of a greater underestimate of SCV incidents for maximum security institutions. Without reliable national statistics however, it is not possible to determine the factors that explain these findings.

Who Tends to be Involved in Incidents of SCV?

Further to the analysis of the Incident Reports, we were able to determine that there was a total of 73 unique victims and 66 unique instigators/perpetrators. The vast majority of cases (85%) involved inmate-on-inmate incidents, whereas 12% involved inmate-on-staff incidents and one incident was staff-on-inmate. Footnote 31

The majority of incidents were reported from men’s institutions; however, while women only account for approximately 5% of the incarcerated population, one-third (33%) of all reported incidents of sexual assault were from women’s institutions. This is consistent with findings from the broader literature on sexual assault, that women are more likely to report sexual assault to authorities than men. This however makes it difficult to determine whether the large proportion of incidents reported from women’s institutions suggests that there are more incidents of SCV in women’s institutions or whether women tend to report these incidents more when they do occur. Once again, national prevalence statistics would provide insights into the source of this difference.

What Types of Incidents Occurred and How Were They Dealt With?

Based on the information that was provided in the Incident Reports, more than half of cases (54%) were classified as unwanted sexual touching or groping, and at least 10.5% involved forced oral and/or penetrative sex. Footnote 32 In 10% of cases, there was information indicating that the victims were double bunked with the alleged perpetrator at the time of the incident. It is likely that the actual number is considerably higher, as the element of double-bunking was not consistently reported.

Based on available information, it is estimated that perpetrators were placed in segregation as a result of the alleged incident in 40% of cases and 10% of victims were also segregated. In nearly all cases (90%), there was indication that the police were contacted; however, charges were laid/pursued in only 12% of cases. The most common reason noted for charges not being pursued was that victims chose not to pursue charges further.

B. Boards of Investigation (BoI) Reports

Of the 72 incidents of SCV that were reported during the five years, a BoI was convened for less than one-third of all reported incidents (i.e., a total of 23 incidents). It is worth noting that, given the criteria for a BoI, incidents for which a BoI was convened likely represent the most egregious cases of SCV and are therefore possibly not representative of the most common types of SCV incidents that occur.