June 26, 2015

The Honourable Steven Blaney

Minister of Public Safety

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 42 nd Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Howard Sapers

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigator's Message

1. Health Care in Federal Corrections

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

5. Safe and Timely Reintegration

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Annex A: Summary of Recommendations

Correctional Investigator's Message

It is a privilege to present my 11 th Annual Report as Correctional Investigator of Canada. Since my first appointment in April 2004, I have been witness to significant changes to the conditions of incarceration and composition of the federal inmate population in Canada. Prison has always shone a spotlight on the problems and inequalities of the larger society in which it functions. This remains true today as substance abuse and addiction, poverty and deprivation, discrimination and social exclusion, mental illness and stigma continue to define and shape modern Canadian correctional policy, practice and populations.

In the ten year period between 2005 and 2015 the federal inmate population grew by 10%. 1 Most of this growth is attributed to steady year-on-year increases in admissions of Aboriginal people, visible minorities and women. During this period, the Aboriginal inmate population has grown by more than 50%. The population of women behind bars increased by over 50% while the number of Aboriginal women inmates almost doubled. Though representing 4.3% of Canadian society, 24.6% of the current total inmate population is Aboriginal; Aboriginal women now comprise 35.5% of the women in-custody population. Over the same period, the Black inmate population grew by 69%. The federal incarceration rate for Blacks is three times their representation rate in general society. These increases continue despite public inquiries and commissions calling for change and Supreme Court of Canada decisions urging restraint.

A look behind the walls today reveals that:

- One in four federal inmates is 50 years of age or older. The population of aging or older people behind bars has risen dramatically, increasing by nearly one-third in the last five years alone.

- Approximately 60% of offenders have employment needs identified at intake to federal custody. Before prison, most are chronically under or unemployed.

- The average level of educational attainment upon admission to a federal penitentiary remains low. More than 60% of offenders at intake have an identified education need, meaning they have not graduated from high school. Over 60% of the overall inmate population has a formal education of grade 8 or less.

- Nearly 4 in 10 male offenders require further assessment at admission to determine if they have mental health needs. 30% of women offenders had previously been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons while fully six in ten incarcerated women are currently prescribed some form of psychotropic medication to manage their mental health.

- Close to 70% of federally sentenced women report histories of sexual abuse and 86% have been physically abused at some point in their life. Their life histories of trauma cannot easily be separated from their conflict with the law.

- 80% of male offenders struggle with addiction or substance abuse. Two-thirds of federal offenders were under the influence of an intoxicant when they committed their index offence.

In correctional language, this profile translates into a high-risk, high-needs population that requires a variety of services and supports, some of which stretch our conventional understanding of what prisons are or what they are supposed to do. Though never intended to serve as psychiatric, palliative or long term care residences, federal correctional facilities are under increasing pressure to perform these functions on a routine basis.

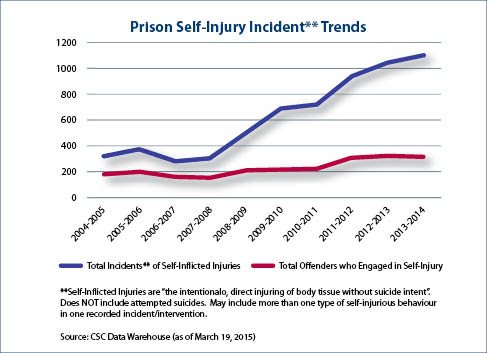

Over the past decade, safe custody indicators have progressively deteriorated. The number of use of force incidents have almost doubled, admissions to administrative segregation increased by 15.5%, incidents of prison self-injury have tripled, prison crowding hit all-time highs and parole grant rates bottomed out. We now have a system that releases the majority of offenders from a penitentiary at statutory release, once they reach the two-thirds point of the sentence. The highest risk and needs offenders, most of whom today are released from multi-security level institutions, are supervised for the least amount of time in the community.

Driven by a changing profile and pushed to address more complex needs, total criminal justice costs (police, courts, corrections, parole) have risen by almost 25% in the last decade, coincidently about the same amount that the national crime rate has fallen. In the ten year period between 2003 and 2013, expenditures on federal corrections grew by just over 70%. At peak spending in FY 2013-2014, CSC 's annual budget exceeded $2.75B. This period also coincided with the single largest expansion of federal correctional system capacity in history which saw the completion of 2,700 new or retrofitted cells at more than 30 different penitentiaries for a total cost of over $700M.

Though spending is starting to come down as a result of various cost containment measures, including CSC 's $300M contribution to the Government of Canada's deficit reduction action plan ( DRAP ) announced in Budget 2012, planned spending for federal corrections in 2015-16 is still $2.35B. It now costs each and every Canadian about $71 annually to operate the federal correctional system. The average cost of keeping a federal male inmate behind bars is $108,376 per year and nearly twice that amount to keep a woman inmate locked up. By contrast, safely maintaining an offender in the community is 70% less.

As my report this year makes clear, inmates are increasingly bearing more of the costs to keep themselves clothed, fed, housed and cared for behind bars. Though inmate pay has not increased since its introduction in 1981 (topping out at a maximum daily wage of $6.90), broader application of room and board deductions have eroded the possibility of having any meaningful savings to support reintegration or maintain familial obligations on the outside. New administrative fees have been added to offset use of the inmate telephone system. Non-essential dental care has been eliminated, as has incentive pay for those employed in the prison industries run by Corcan. Though modernization of the prison food preparation, delivery and distribution system (known as cook-chill) has resulted in some cost efficiencies, its introduction has led to a perceptible decline in the overall quality, selection and quantity of food being provided. It has also significantly reduced the number of available jobs to inmates and resulted in reduced training opportunities.

Other cost-saving measures, such as the closure of prison farms, cutting funding for reintegration and release programs such as Lifeline and Circles of Support and Accountability or reduced funding for access to psychological services in some communities serve to effectively undermine reintegration efforts. At best, the savings achieved as a result of these measures are modest, but the implications can be profound in terms of negative impact on correctional progress and access to safe and timely reintegration and support.

Meantime, a whole other series of sweeping business transformation decisions amalgamation/clustering of institutional services, realignment of case management activities, realignment of resources within treatment centres, streamlining of national and regional headquarters, and renewal of funding formulas effectively translate into doing more with less. Few of these administrative measures are supported by evidence and most have no demonstrated link to increased public safety. It is not difficult to envision the larger ramifications of these service reductions. Inmates who become hardened by their prison experience and whose needs are left unaddressed are less likely to benefit from their incarceration and be much less adequately prepared for release. Put simply, cuts to inmate services may actually serve to increase risks to public safety rather than decrease them.

The past five years have seen an unprecedented number of sentencing and policy reforms. Taken together, their cumulative effect has profoundly changed the discourse and practice of criminal justice in Canada, and has contributed to the erosion of some long-standing evidence-based correctional principles and practices. I remain particularly concerned that concepts such as the least restrictive measure and retained rights have been eroded or replaced with more ambiguous language, such as proportionate and necessary measures. Amendments to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act now make it clear that the sentence is to be managed according to the nature and gravity of the offence and the degree of responsibility of the offender. Public safety, instead of being an outcome of a fair and balanced system, has become the dominant principle, overshadowing all other equally valid purposes such as rehabilitation and safe reintegration.

We are beginning to see the impact of these changes on operations. Static risk factors (nature of the offence, gravity of the offence, sentence length) are more prominent in liberty decisions affecting security classification, penitentiary placement and access to the community. Even so, managing a sentence of imprisonment based on the severity (or notoriety) of the crime rather than respecting the principles of individuality or proportionality defies much of what we know about modern risk management. Corrections is in the business of promoting personal change and reform; it is a forward, not backward looking enterprise. Its focus properly belongs on assessing criminological risks and need as they evolve over time.

With the renewed emphasis on detention, the correctional and parole systems have devolved more or less accordingly, to the point where there is little tolerance for even well managed risk. As I suggest in this report, the system has become so risk averse that even elderly, chronically ill and geriatric persons who no longer pose any ongoing or dynamic risk to public safety are commonly held to their statutory or warrant expiry dates. Ironically, and defying evidence, longer and harsher penalties that result in less time served in the community are actually predictive of reoffending. We seem to be looking back in time, to the nothing works era, when the most we expected from our prisons was secure custody and prisoners were considered to be less than citizens or bearers of rights.

The corrections policy agenda has spawned robust public debate, not all of it supportive of the government's intent or direction. A number of measures have been successfully contested in the courts, challenged on procedural, fairness and Charter grounds. For example, the courts ruled against the government's attempt to retroactively eliminate the possibility of accelerated parole review for offenders who had already been sentenced. Court rulings also struck down as unconstitutional changes limiting inmates' credit for time spent in pre-trial custody. The Supreme Court has ruled that mandatory minimum penalties for some gun crimes violate the Charter. Meantime, the mandatory victim surcharge resulting from the Increasing Offenders' Accountability for Victims Act is still an unsettled matter. I have every expectation that the number of legal challenges will grow as offenders seek judicial relief from conditions of detention and policy reforms that are felt to be unlawful or unjust.

It may be my own bias and experience, but I believe that in this environment robust independent oversight, openness and transparency are more critical than ever. It is important that acts and decisions involving the care and custody of those deprived of liberty are viewed through a human rights and fairness lens. We know from experience that sentenced individuals have the best chance of success upon release when they have been treated fairly, when they have access to programs and interventions that are matched to need and risk and when these supports are delivered by the right people at the right time in the sentence. We can best manage risk when we apply these lessons, not ignore them. This does not mean that offenders deserve special or enhanced rights or that their offences should be consequence free. It does mean that when someone loses their liberty as a result of incarceration, evidence supported policy and the rule of law must follow them through the prison gate and be applied throughout their sentence.

In my 11 years as Correctional Investigator, I served under two Prime Ministers and dealt with five different Ministers of Public Safety and three Commissioners of Corrections. I provided testimony to numerous Parliamentary Committees responding to an unprecedented volume of criminal justice reforms. I estimate that approximately 200,000 calls and complaints were handled during my tenure. In this challenging environment, I was always well supported by professional and dedicated staff. During my term, approximately 90 men and women have worked in the Office. To a person, they proved what a small team of dedicated public servants can accomplish. Intake officers, analysts, investigators, human resources and administrative personnel, policy advisors, managers and directors functioned cohesively and maintained a very high tempo. Their work was at times emotional and always demanding. Clients and all Canadians are better off for their efforts. I give them my heartfelt thanks.

As I complete my term, I want to take this opportunity to say what an honour it has been to have served Canada as Correctional Investigator. It has been a rewarding and life-enriching experience on so many levels. As I make the transition from this part of my public service career, I would remind Canadians and parliamentarians alike that due process, fairness, proportionality, rationality and compassion are hallmarks of an excellent criminal justice system. Human decency and dignity are principles to be nurtured and protected even, and perhaps especially, for those among us deprived of their liberty. To do otherwise, is to diminish our own humanity.

Howard Sapers

Correctional Investigator of Canada

June, 2015

Executive Director's Message

2014-15 was another productive year for the Office. The investigative team handled one of the highest caseloads in recent years responding to more than 6,200 offender complaints. Investigators conducted 2,110 interviews with offenders and staff and spent a cumulative total of 381 days visiting federal penitentiaries across the country. The intake staff fielded more than 22,000 phone contacts. The Office's use of force and serious incident review teams conducted 1,510 uses of force compliance reviews and 167 mandated reviews involving assaults, deaths, attempted suicides and self harm incidents. On the policy side, the Office completed two national systemic investigations in the reporting period A Three Year Review of Federal Inmate Suicides (2011 2014) as well as an investigation of CSC 's National Drug Formulary.

Along with supporting the Correctional Investigator's public engagements, this collective output represents a remarkable workload accomplishment for a small oversight body of 36 full-time employees and an annual budget of $4.0M.

Corporately, for the first time in its history, the Office participated in the Public Service Employee Survey and is in the process of developing an action plan to address workplace issues identified in the survey. The Office's Destination 2020 activities were led by an internal working group which developed both near and longer term recommendations to embed new technologies and innovations into the OCI work environment. In line with the core public service, the corporate stream led the development of policy directives for the Office's performance management framework, including individual evaluation criteria for the investigative, policy, intake and corporate streams.

In the year ahead, the Office will implement a number of process improvements to support a variety of work activities: a system to better manage Access to Information and Privacy requests; a correspondence tracking tool, and; a new platform to replace the Office's shared case management records system.

2015-16 will also be a time of transition for the Office as it engages in a strategic planning exercise to renew its direction, set corporate priorities and identify investigative plans over a five-year horizon.

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Executive Director and General Counsel

1. Health Care in Federal Corrections

Issues in Focus

Estimates of Chronic Disease Prevalence among Federal Inmates

| Respiratory illness | 15.4% |

| Hypertension | 16.0% |

| Diabetes | 8.0% |

| Hepatitis C | 16.5% |

| Living with chronic pain | 27.0% |

| Addiction history (drug or alcohol) | 52.5% (shows signs of substance dependence) |

| Overweight or obese | 68% (increasing to 90% for those aged 65 or more) |

Sources: Stewart, L.A., Sapers, J., Nolan, A., & Power, J. (2014). Self-Reported Physical Health Status of Newly Admitted Federally-Sentenced Men Offenders. Research Report R-314. Ottawa, ON: Correctional Service of Canada.

Beaudette, J.N., Power, J., & Stewart, L.A. (2015). National Prevalence of Mental Disorders among Incoming Federally-Sentenced Men Offenders. Research Report, R-357. Ottawa, ON: Correctional Service of Canada.

Physical Health

It is universally established that correctional facilities house a number of health-compromised and vulnerable individuals who have often lived on the margins of society. Deficits in literacy, education, housing, employment, social support networks, income and social status are all associated with increased health morbidity and premature mortality. A criminal lifestyle often puts offenders at greater risk of developing chronic health problems. Mental illness, drug dependence and infectious diseases are among the most prevalent health problems of offenders.

As a difficult to serve population, many offenders have little or no regular contact with health services before incarceration. They often come into prison with unmet and untreated chronic health conditions. This situation presents both challenge and opportunity for the Correctional Service. Since health care invariably involves decisions about personal autonomy, consent and control, offender health care concerns access to health care services, quality of health care provided and, increasingly, decisions regarding prescription medication use often rub up against other competing operational priorities, such as security, population movement, institutional routines, and staff availability to provide escort to access community health care specialists and providers.

On the other side of the equation, prison is sometimes the only opportunity for an ordered approach to assessing and addressing the health needs of prisoners who have led chaotic lifestyles prior to imprisonment. 2 It is therefore important to work towards a healthy prison model, an approach that embodies primary health promotion, screening and assessment, disease prevention, treatment and control, and harm reduction.

In response to a number of health-related offender complaints, the Office conducted a series of health-focused reviews in 2014-15. The results of these reviews and investigations are reported below.

Investigation of CSC 's National Drug Formulary 3

Similar to provincial publicly funded drug plans, CSC 's National Drug Formulary lists the medications that CSC will fund for federal inmates. The Formulary provides CSC physicians and pharmacists access to cost- effective drug therapies that are safe and appropriate to use in a prison context. Wherever possible, CSC regional pharmacies provide interchangeable generic drug products. According to CSC , introduction of the National Formulary in 2009 has created consistency in medication access across the country.

The Office contracted with two outside medical doctors to assist in the review of the Formulary. These two physicians were specifically requested to focus on access to drug therapies involving chronic pain management and psychotropic medications. The Office also reviewed CSC healthcare policy and conducted qualitative interviews with sixteen institutional physicians as well as Health Services management at national headquarters.

Although the National Formulary was found to be generally comprehensive and comparable to provincially funded drug plans, the Office identified a number of specific process improvement issues:

- Newly admitted offenders and those transferring to institutions are often subject to interruptions in pharmaceutical care (i.e. prescription medications suddenly stopped, withdrawn or altered).

- Decisions on non-formulary requests were not consistent nationally or even within a region.

- Treatment options listed on the Formulary and physician autonomy were found to be restricted often as a result of ill-defined security, administrative or operational concerns.

- For certain medical conditions (chronic pain and Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder), the Formulary does not provide sufficient treatment options.

The review contained ten recommendations. Key among them were:

- New admissions to federal custody with a valid prescription or who require medical treatment should be seen by an attending institutional physician within 72 hours of being admitted.

- CSC should immediately amend policy to ensure medications are not abruptly stopped or altered for offenders being transferred before an in-patient assessment is completed.

- CSC should implement a national electronic pharmaceutical database to provide reliable data on drug utilization trends.

- CSC should conduct an administrative review of the non-formulary request process responsive to issues identified in this review, including an assessment of the appropriateness of Regional Pharmacists making the final decision on non-formulary requests.

- In consultation with institutional physicians, CSC should amend areas of its Formulary where sufficient treatment options appear to be lacking (e.g. Psychotherapy, chronic pain management, Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder).

CSC 's response to these recommendations was mixed. It accepted that medication reconciliation can be a challenge, but it rejected the claim that changes or alterations to prescription medications is a common practice especially for new admissions entering federal custody and in cases where an inmate is transferred from one CSC facility to another. Nonetheless, the practice of abruptly withdrawing or altering prescription drug therapies at the receiving facility was well documented and is particularly concerning in cases where an inmate is discharged from a treatment centre and returning to his/her parent institution with a new or different drug treatment regime. As the investigation finds, an interruption or alteration in pharmaceutical care may be particularly inappropriate or unsafe for first time federal offenders with a mental health condition.

Another problematic area identified in this investigation is the Regional Pharmacist's ability to refuse medications not covered by the Formulary without consulting with the prescribing physician. While Physicians are required to provide justification for their non-formulary request, some questioned the appropriateness of a process that allows the Regional Pharmacist to refuse a prescribed drug therapy even though s/he may have no firsthand knowledge of the case or clinical contact with the patient. Though CSC committed to bring this issue and a few others forward to its National Pharmaceutical and Therapeutics Committee, it is not clear that these procedural deficiencies will be quickly resolved. Enhanced or facilitated communication between Regional Pharmacists and institutional physicians is an easy fix that must be pursued.

Overall, the investigation affirms that there is room and opportunity to make process improvements to CSC 's National Drug Formulary. The Health Services Branch at national headquarters is encouraged to make them happen.

Access to Emerging Hepatitis C Therapies

In response to a number of offender complaints involving access to new and potentially game-changing Hepatitis C ( HCV ) therapies not currently listed on CSC 's drug formulary, the Office undertook a review of the issues at stake for federal corrections including the status, availability and costs of current and emerging hepatitis C infection treatments. 4 Based on testing and screening surveillance data, CSC reports that the prevalence of HCV infection among inmates was 17.2% in 2013. Based on a combination of self-reported and epidemiological data, the estimated prevalence rates of HCV infection are thirty to forty times higher in prison than in the Canadian population. 5

The treatment of HCV infection is a rapidly evolving field. Health Canada has approved a number of new drug therapies since 2013 which have higher cure rates, fewer side effects and are of shorter duration. While these therapies are costly, emerging HCV treatment options might best be considered a short term investment that has long term public safety and health benefits. Prevention, control and treatment of infectious diseases within federal correctional facilities needs to be seen as a public health issue. Access to treatment therapies, combined with harm reduction measures inside prisons, helps decrease the risk of transmission once an offender is returned to the community.

1. I recommend that CSC prepare a business case to seek additional funding this fiscal year to expand inmate access to evolving Hepatitis C therapies. This initiative should be framed as an investment in public health and public safety.

Drug Utilization Evaluation

In response to information and criticisms suggesting that psychotropic drugs are over-utilized in CSC , particularly among federally sentenced women, CSC agreed to conduct a Drug Utilization Evaluation using a representative random sample. Because CSC does not currently have a national electronic pharmaceutical database, this review requires manually pulling and coding health care files and information. The initial phases of this project will prioritize women offenders. This is important baseline data that assists in estimating the prevalence of certain mental health conditions among the offender population. Together with the ongoing review of estimates of chronic disease prevalence among federal inmates these information sources should be used to develop appropriate, evidence-based health care management responses and strategies. Based on the initial return and review of chronic disease prevalence estimates, it is encouraging that the Service is focusing near-term efforts on diabetes, cardiovascular and chronic respiratory illnesses.

2. I recommend that CSC 's efforts to establish prevalence estimates for chronic physical and mental health conditions be complemented by a comprehensive analysis of annually tracked and reported trends and causes of natural mortality among the federal inmate population.

Care and Custody of Elderly/Geriatric Offenders

My 2010-11 Annual Report contained a special focus on the issues and challenges facing aging/older offenders in federal prisons. At that time, the older offender population (age 50 and older) represented fewer than 20% of the total inmate population. 6 Today, the proportion of the inmate population over the age of 50 is just under 25%, an overall increase of nearly one-third in the last five years alone. 7 The growing number of older people behind bars is the result of the combined demographic effects of a general population that is aging, more offenders entering prison later in life, offenders staying longer in prison before release and the accumulation of long-serving, indeterminate or life-sentenced offenders. Today, one in four federal inmates is a lifer.' Despite rhetoric to the contrary, a life sentence in Canada does in fact mean life; all lifers' will die while still under sentence.

As these trends accelerate and intensify, the Service is struggling to keep pace with their implications. In general, older offenders pose less institutional and public safety risk, but they have greater health needs. From a fiscal perspective, the aging offender population is a principal driver of rising costs of prison health care. Some older offenders are, or will become chronically or terminally ill during the course of their incarceration; some will require palliation and die from naturally attributed causes in prison. Older offenders experience greater hardships in prison, have worse health outcomes, and are one of the most expensive age cohorts to incarcerate while posing the least risk to public safety.

In light of the growing number of older people behind bars, prison-based health care service delivery models need to be re-considered, including the possibility of designating particular institutions or ranges within a penitentiary as geriatric wards staffed with specialized, team-based health care workers gerontologists, palliative care specialists, occupational therapists, audiologists. Currently, some institutions have trained and employed other inmates to provide basic palliative care services activities such as changing bedding and clothing, aiding in hygiene and feeding, as well as keeping palliative inmates company throughout the day are performed by peers. These initiatives should be further encouraged and developed.

3. I recommend that CSC engage its Health Care Advisory Committee to develop a chronic/long-term care model that is responsive to the needs of the growing number of older/geriatric people behind bars. The model should be presented in time to influence CSC 's 2016-17 operational budget.

Accreditation of CSC Health Care Services

CSC Health Services participates in Accreditation Canada's program of accreditation, which independently sets standards for quality and safety in health care settings in Canada and around the world. As part of the program of accreditation, CSC facilities are periodically subject to on-site visits. The latest visits took place between April June 2014 and a report was issued in September 2014. While CSC maintained its accreditation status, overall there were a number of areas requiring improvement at the institutional, regional or national level including:

- Physical infrastructure and space limitations affecting the ability of health care staff to provide safe and optimal care.

- Meeting complex health care needs of an aging inmate population.

- Resolution of role and ethical conflicts (health care needs of offenders viewed as secondary to security or operational demands).

- Unmet standards of infection prevention and control.

- Lack of an electronic medical records system in federal corrections.

- National resource allocation standards and funding formulas, including nurse-to-patient ratios.

- Unmet clinical leadership criteria in mental health services.

Most of these issues are not new to CSC . I have every expectation that the unmet standards identified in the latest accreditation of CSC health services will be addressed and that the program will be used to drive continuous quality improvement in the delivery of patient programs, policies and practices.

4. I recommend that CSC immediately produce an Action Plan detailing the steps to be taken to address the issues of concern identified in the September 2014 Accreditation Canada report. This plan should be vetted at the next meeting of the Health Care Advisory Committee.

Mental Health

Issues in Focus

Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders among Incoming Male Federal Offenders

Sample of Incoming Federal Offenders (N = 1,110 men)

| Mental Health Disorder | Prevalence Rate % |

| Mood Disorders | 16.9% |

| Primary Psychotic | 3.3 % |

| Alcohol or Substance Use Disorders | 49.6% |

| Anxiety Disorders | 29.5% |

| Pathological Gambling | 5.9% |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 15.9% |

| Antisocial Personality Disorder | 44.1% |

Source: Beaudette, J.N., Power, J., & Stewart, L.A. (2015). National Prevalence of Mental Disorders among Incoming Federally-Sentenced Men Offenders (Research Report, R-357). Ottawa, ON: Correctional Service Canada.

According to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , the term mental health care means the care of a disorder of thought, mood, perception, orientation or memory that significantly impairs judgement, behaviour, the capacity to recognize reality or the ability to meet the ordinary demands of life. These disorders are increasingly common among the offender population reflecting broader developments in the criminal justice, mental health, legal and social systems. Federal prisons now house some of the largest concentrations of people with mental health conditions in the country.

Comprehensive and reliable prevalence data for existing mental health disorders among the total inmate population is not available. A 2015 sampling of incoming male offenders to federal custody suggests very high prevalence estimates for certain disorders. It is estimated that mental health issues are two to three times more common in prison than in the general community. Close to half of incoming male offenders have alcohol dependence or substance use disorders while more than one-third of offenders meet the criteria for concurrent disorders, indicating high rates of co-morbidity. Though known prevalence is high for many mental health disorders, the actual rates could be even higher. 8

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

Estimates of FASD prevalence among correctional populations vary significantly, with numbers ranging from 9.8% to 23.3%. 9 In 2011, the CSC conducted a research study of FASD prevalence in a federal correctional population. 10 It found that, among a sample of newly admitted adult male offenders (age 30 and under), 10% of participants met the criteria for FASD . Another 15% of the sample met some of the diagnostic criteria, but were missing information critical to making or ruling out a positive diagnosis. The rate of FASD among this sample is 10 times higher than current general Canadian incidence estimates (9 in 1,000 according to Health Canada).

Interestingly, none of the offenders diagnosed in this research study had been previously identified as being FASD -affected. As the research concludes: there is a population within CSC who are affected by FASD who are currently not being recognized upon intake, and are not being offered the types of services or programs that meet their unique needs. Screening to identify those at risk for FASD is necessary and has been demonstrated as feasible in a correctional context.

Four years later, CSC still does not have a reliable and validated system to screen, assess and diagnose FAS Disorders among newly admitted federally sentenced offenders. This is a vulnerable population with significant mental health and behavioural needs. A more recent sample of inmates living with FASD in a federal penitentiary suggests that these offenders exhibit neuropsychological deficits in attention, executive functioning and adaptive behaviour that impact their ability to adjust to an institutional setting. They were much more likely to have had multiple convictions and previous periods of incarceration as both youth and adults. While incarcerated, they are more likely to be involved in institutional incidents, both as instigators and as victims, and to incur institutional charges. They complete their correctional programs at much lower rates, and they typically spend more of their sentence incarcerated before first release. Offenders with FASD are more likely to be returned to the community on statutory release. 11

The range of cognitive deficits that characterize FASD difficulty understanding consequences of behaviour, inability to make connections between cause and effect, impulsivity, drug or alcohol problems, failure to learn from mistakes have important legal and practical implications for the criminal justice system writ large. 12 The unfortunate reality is that a significant proportion of FASD -affected offenders still enter prison today undiagnosed and they remain untreated throughout their incarceration. Though CSC can and does adapt programs to accommodate learning styles and needs, there are no interventions specifically for offenders with FASD . There is evidence to suggest that individuals with FASD benefit from programs that are structured, provide repetition and use multiple modalities. Without specialized programs, supports and services, the outcomes for offenders with FASD are considerably compromised. Though such strategies exist, there is a prerequisite to identify those offenders with cognitive deficits who could benefit from adapted interventions. Footnote 13

5. I recommend that CSC establish a standing expert advisory committee on FASD to establish prevalence, provide advice on screening, assessment, treatment and program models for FASD -affected offenders. The Committee should recommend a FASD strategy for CSC 's Executive Committee in the next fiscal year.

Optimal' Model of Mental Health Care

To manage the rising number of offenders with mental health issues, to contain costs and better match service level with predicted need, the Service is implementing what it calls an optimal' (or refined') model for mental health service delivery. Under this model, some existing treatment bed spaces at its regional treatment facilities will be de-listed.' With the savings generated, CSC will repurpose treatment capacity to add intermediate care both at the treatment centres and at some of its penitentiaries. At the end of the reporting period (March 31, 2015), the CSC had plans to increase the total number of mental health beds in federal corrections to 778, which includes 150 psychiatric beds and 628 intermediate-level care bed spaces. While the designated intermediate care capacity is new, it seems to come at the expense of approximately 500 psychiatric treatment beds.

The initial estimates of required mental health bed capacity (or the optimal' mix between acute and intermediate care) are based on mental health prevalence data contained in an internal report commissioned by the Service. This September 2013 report, based on a model of mental health services promoted by the World Health Organization, 14 estimates that about 3.5% of the inmate population requires acute mental health intervention and that another 6.4% require a degree of intermediate level care. Though CSC 's estimated bed requirements use more elaborate models and methods (including length of stay), based on a total in-custody population of approximately 15,000 the Office estimates that CSC actually requires more than 500 acute psychiatric care beds and nearly 1,000 intermediate beds just to keep pace with current needs and demands. In other words, the refined model could be short by about half the number of required bed spaces to match current, let alone, future needs. 15

Under the plan, hundreds of formerly designated acute psychiatric hospital beds will be eliminated and replaced by intermediate bed spaces. The impact of these changes at the local and regional level is considerable. For the Atlantic Region, repurposing of the Shepody Healing Centre, which is co-located within the Dorchester Penitentiary complex, has meant transferring some patients with severe mental illness to other regions, including Quebec, where language, culture and separation from family may pose significant barriers. As a national federal entity, the Service has a legal responsibility to ensure equality of access to essential health care services even in under-serviced regions. The optimal model of care being implemented nationally must respect variation in levels of access to care or service delivery capacity across Canada's five regions.

It is troubling that intermediate care capacity is being made possible through the elimination or reduction of psychiatric care beds across the country. De-listing or conversion of psychiatric hospital beds to create and pay for intermediate care capacity needs has regulatory, oversight and accreditation implications that do not seem to have been taken into account. Through all of this, it is not clear how a reduction in psychiatric beds can possibly lead to an optimal or efficient model of mental health care service delivery. Indeed, from the Office's perspective, the assumptions and estimates of prevalence informing this model have not been subject to sufficient independent analysis, testing or corroboration.

6. I recommend that the Department of Public Safety commission, in partnership with Health Canada, an independent validation of CSC 's optimal' model of mental health care and report findings to the Minister of Public Safety.

CSC 's Response to the Ashley Smith Inquest

CSC 's long-awaited response to the inquest into the death of Ashley Smith was finally released on December 11, 2014, nearly one year after the verdict and 104 recommendations were delivered by the Ontario Coroner, 16 and fully seven years after Ashley died in a segregation cell at Grand Valley Institution for Women in October 2007. 17

The response itself, both in form and content, is frustrating and disappointing. Organized thematically around five pillars' previously announced by the Minister of Public Safety in an interim response ( Mental Health Action Plan for Federal Offenders ) in May 2014, the response fails to specifically address individual jury recommendations. This approach makes it difficult to know which recommendations are endorsed and supported versus those that have been rejected, ignored or supported only in part.

CSC claims that a thematic response was called for given that the jury's 104 recommendations covered a wide spectrum of issues. Though it refers to its response as meaningful, comprehensive and encompassing, this is not a widely held view. Public and stakeholder commentary both on the day of release and since has not been favourable.

On many fronts, the response simply misses the mark. It is largely retrospective and backward-looking covering familiar territory rather than committing to a more reform-minded correctional agenda. It fails to support core preventive, oversight and accountability recommendations issued by the jury.

I have raised these and other concerns in my exchanges with the Minister of Public Safety. I have suggested to the Minister that there still remains an opportunity and expectation that unsupported recommendations will be acted upon:

- Prohibit long-term segregation (in excess of 15 days) of mentally disordered inmates.

- Commit to move toward a restraint-free environment in federal corrections for mentally ill offenders.

- Appoint independent patient advocates and rights advisors at each of the Regional Treatment Centres.

- Provide for 24/7 on-site nursing services at all maximum, medium and multi-level penitentiaries.

- Give clear and direct line authority to the Deputy Commissioner for Women for all matters relating to the care and custody of federally sentenced women.

- Promulgate policy and practices that are more responsive to the unique needs of younger offenders (age 25 and under).

- Establish a 5-year internal audit plan on key concerns identified in the Jury's inquest recommendations regarding legal and policy compliance

One of the most frustrating aspects of this file has been CSC 's decision to delay response to some outstanding reports and recommendations of my Office as it considered its response to the Inquest. In practical terms, this has meant that, until recently, I did not have a response to Risky Business (An Investigation of the Treatment and Management of Chronic Self-Injury among Federally Sentenced Women), a report that was originally released in September 2013. Responses to a handful of mental health care and use of force recommendations made in my 2012-13 and 2013-14 Annual Reports were also delayed, as was the response to my Office's Three Year Review of Inmate Suicides , released on World Suicide Prevention Day (September 10, 2014). 18 CSC claimed it needed time to complete a thorough and integrated review of the implications of these reports and their recommendations before responding.

I have since requested and been provided additional information about some of the new or ongoing initiatives that CSC is pursuing following its response to the inquest. These initiatives include:

- CSC 's initiative to identify newly admitted offenders who may be at risk of becoming segregated early in their sentence.

- Research project on the effectiveness of CSC 's Segregation Intervention Strategy.

- Details of CSC 's Segregation Renewal Strategy, including proposed regulatory amendments to administrative segregation.

- Review of the Situational Management Model to medical emergencies, incidents of self-injurious behaviour and offenders with mental health disorders.

- Status of partnerships with provincial forensic hospitals for inpatient psychiatric care.

- Implementation of the optimal mix of mental health care services and repurposing of existing hospital beds to intermediate mental health care beds.

- Case Study on Ashley Smith's experience.

It is clear from these ongoing commitments that the Ashley Smith file is far from closed. This Office will continue to hold the Service answerable and accountable for commitments that have been made, as well as those that still remain unfulfilled.

Prison Self-Injury

Self-inflicted injuries in federal prisons are increasing, more than doubling over the past 5 years. In 2013-14, there were 578 self-injurious incidents involving 60 different federally sentenced women inmates. The five most chronic self-injurious female offenders accounted for 58.3% of all self-injurious incidents involving women. Together, these women accounted for almost one-third of the total self-injurious incidents among the entire inmate population. Two of these women were Aboriginal. Nearly three-quarters of all incidents involving women occurred at one facility the Regional Psychiatric Centre ( RPC ), Saskatoon.

The five most chronic self-injurious male offenders accounted for 14.8% of all incidents involving men. Three of the five most chronic self-injurious male offenders were Aboriginal. For men, 55.3% of all self-injury incidents took place at the Regional Treatment Centres. This is perhaps not surprising, given that men and women offenders who reside in treatment centres are more likely to meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder as well as to have experienced childhood sexual, emotional and physical abuse, and emotional neglect. 19

In 2014-15, a use of force intervention was reported in 16.3% of all self-injurious incidents, repeating a pattern in which behaviours associated with mental illness are often met by a security versus therapeutic response. As detailed in Risky Business , I continue to be concerned about CSC 's management of chronic self-injury, particularly the use of segregation and restraint equipment to control or manage serial self-harm. More and more research has established links between self-injurious behaviour and traumatic experiences. This relationship appears predictive in both men and women offenders engaged in chronic self-injurious behaviour in prison settings. This knowledge should help inform individualized treatment and intervention plans for these offenders.

7. I recommend that CSC examine international research and best practices to identify appropriate and effective trauma-informed treatment and services for offenders engaged in chronic self-injurious behaviour, and that a comprehensive intervention strategy be developed based on this review.

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

Prison Suicide

Suicide is the leading cause of un-natural death in federal prisons, accounting for about one-in-five deaths in custody in any given year. 20 The rate of prison suicide has been declining, but it is still several times higher than in the general population. 21

To mark World Suicide Prevention Day, on September 10, 2014 the Office released an investigative report that examined 30 inmate suicides that occurred over a three year period (2011 to 2014). 22 As the review makes clear, most of those who commit suicide in prison have a documented mental health issue or a history of attempted suicide, suicidal ideation or self-harming behaviour. Just under half of those who ended their life in prison were prescribed psychotropic medications at time of death, a potential precipitating factor also raised in the report by the 2nd Independent Review Committee into federal deaths in custody. 23

The most disturbing finding of this review was that 14 of the 30 suicides took place in segregation cells. Segregation placement was found to be an independent factor that elevated suicidal risk. Nearly all of the segregated inmates had known mental health issues; most were or had been referred and/or seen by mental health staff while on segregation status. Significantly, ten of the 14 inmates who committed suicide in segregation were beyond the 15 day mark; five in fact had been held in segregation for more than 120 days prior to taking their life. The fact that segregated inmates had both the means and opportunity to end their lives in an area of the prison that is supposed to be safe and subject to continuous monitoring represents a serious organizational vulnerability.

Issues in Focus

A Three Year Review of Federal Inmate Suicides (2011-2014)

Major Findings

- Most inmates who commit suicide are unmarried, Caucasian males, 31-40 years of age.

- 14 of the 30 suicides occurred in segregation cells. Almost half were incarcerated in medium security; 9 in maximum security.

- Most had previously attempted suicide; seven more than twice. Nearly 25% expressed suicidal ideation in the days leading up to their death.

The report raises the possibility that some of these suicide deaths could have been averted through more rigorous screening procedures, better information sharing or more timely access to mental health services. The investigation highlighted some recurring risks and gaps in CSC 's overall deaths in custody prevention strategy:

- Management of mentally disordered offenders in segregation

- Quality of post-incident investigative reviews

- Segregation placement as an independent factor in deaths in custody

- Screening, identification and monitoring of suicide risk (precipitating factors)

- Failure to learn from repeated mistakes

I concluded my review of prison suicide with pointed criticism of the Service's internal investigative process:

A major impediment to progress appears to be the lack of immediate and substantive follow-up, especially dissemination of lessons learned from boards of investigation across a very decentralized Service. The fact that corrective measures are brought forward to senior management normally several months (or even years) after the incident invariably raises the likelihood that the same organizational shortcomings are permitted to be perpetuated over and over again. Focused almost exclusively on operational compliance, audits and post-incident investigations pay surprisingly little attention to organizational risks and environmental hazards (e.g. access to mental health treatment and supports, segregation as an independent variable, access to in-cell suspension points) that should have been reasonably expected to have been mitigated .... Lessons learned from even a single suicide should have a lasting impact on the organization and its efforts to prevent and publicly account for deaths in custody. Post-incident investigations should drive needed transparency and accountability reforms ... 24

CSC is taking some steps to address this criticism. A series of internal documents Lessons Learned Bulletins, Discussion Guides and Thematic Analysis are being produced by the Incident Investigations Branch to facilitate and encourage broader exchange and sharing with front-line staff of recommendations, best practices, and corrective measures drawn and derived from national investigations. The collective focus of this effort is on learning and fostering improvement. This work is to be encouraged, expanded and embedded across the Service.

There are several other ways for CSC to enhance its prevention efforts. Four years have now passed since the Service published its last Annual Inmate Suicide Report (an initiative that dates back to 1992). Three years after committing to do so, the Service finally has issued its first annual public report on deaths in custody. 25 There appears to be no Government of Canada interest in creating an independent national advisory forum to share information and lessons learned to reduce the overall number and rates of in-custody deaths in Canada. CSC continues to place mentally disordered, self-injurious and suicidal inmates in long-term administrative segregation in cells with known suspension points. The Service also continues to reject calls for the routine and timely sharing of investigative reports into deaths in custody with designated family members, as well as provincial and territorial Coroner and Medical Examiner Offices.

These are all missed opportunities that could help foster a more accountable, open and transparent correctional system. I suggest that these deficiencies would not be tolerated in any other institutional care setting. To do so in our prison system is contrary to the duty of care owed to those under state control.

Natural Cause Deaths in Custody

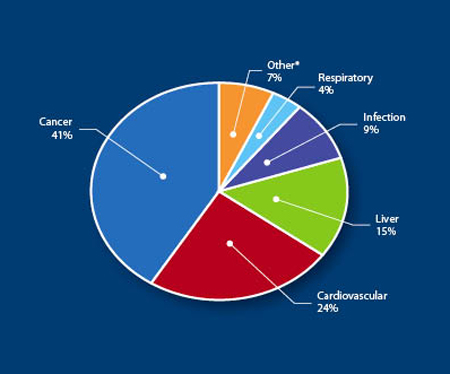

As more offenders age behind bars a greater percentage of the population is succumbing to chronic disease and mortality. In 2014-15, there were 43 deaths in CSC facilities preliminarily attributed to natural causes. Reflecting a growing number of older/elderly people behind bars, the yearly number of natural cause deaths now far exceed all other non-natural causes of death behind bars combined (suicide, murder, overdose, accident). Natural cause mortality (and the costs associated with end of life care in prison) can be expected to increase even further as the inmate population, like the rest of Canadian society, ages.

During the reporting period, CSC assembled a team to address the backlog of mortality reviews that had yet to be convened; some of these deaths dated back to 2011. The findings from the backlog of 94 cases have some important policy and practice implications for prevention of deaths in custody. As indicated, similar to national mortality rates cancer is the leading cause of natural death among the inmate population. Cardiovascular issues accounted for 24% of deaths behind bars. Liver (cirrhosis or liver failure) was fatal in 15% of cases followed by infection (9%) and respiratory failure (4%). 36% of all natural cause deaths were deemed unexpected the result of sudden cardiac arrest, complications arising from medical procedures or rapid disease progression.

Significantly, nearly 60 of the natural cause deaths involved individuals who were receiving palliative care (including end of life) services. Of those palliation cases, 60% died in a CSC regional hospital, 31% died in a community hospital and 9% succumbed in a CSC institution. Though prisons were never meant to serve as hospitals, nursing homes or hospice facilities, they are increasingly under strain to perform these functions.

Issues in Focus

Natural Mortality in Federal Prisons

Cause of Death n=94

Average age at time of death: 60 years.

* Other includes: Alzheimer's disease, post-operative complications, gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure and necrotizing pancreatitis.

Source: Correctional Service of Canada. Health Services Mortality Review: Review of Revised Process. Presentation Deck (March 5, 2015).

Parole by Exception (compassionate release) provisions of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act were explored in 36 of 55 of the palliative care cases. Of those, 14 applications were made to the Parole Board of Canada for review; only 4 were granted. In 19 of 55 palliative cases, the rapid course of illness did not allow sufficient time to explore alternatives to incarceration. Five inmates refused to submit an exception request; for some their wish was to remain at a CSC facility to receive end of life care. Managing palliation in a prison setting is challenging to say nothing about the erosion of human dignity that dying behind bars implies.

In 2014-15, the CSC implemented a number of changes to its mortality review process, many of which were responsive to issues raised and recommendations made by this Office. 26 Significant among them is the strengthened role of the Senior Medical Advisor who now has more direct involvement in the decision to convene and proceed with a natural mortality review. The Medical Advisor also now chairs and signs off on mortality reviews bringing more rigour and focus on the cause of death and the relevant medical events preceding death. Together with a more timely, effective and focused review of the cause of death, CSC is expecting to produce results in real time yielding quicker attention to meaningful corrective measures and quality improvement initiatives in health care delivery.

A key criticism of the mortality review process is that it rarely yielded any findings or recommendations of national significance. As the backlog of mortality reviews finally makes its way to my Office, I expect to see that the revamped process addresses this major organizational weakness. Mortality reviews should also more directly link with health strategies to prevent, manage and treat the onset of chronic disease and illness behind bars.

Directions for Reform

Quite apart from these internal procedural reforms, I remain concerned that the average age of federal offenders who die either in custody or under sentence in the community of natural causes is far below national life expectancies. The average age at death for a federal inmate is low (averaging around 60 years), much younger than the Canadian life expectancy of 78.3 years for males and 83 years for females. This trend of premature death holds consistent for offenders still under sentence in the community where the average age of death is 62.5 years. Though offenders tend to come to prison in much poorer physical, mental and social health than the population at large, it is my belief that a federal sentence should not, in and of itself, be predictive of a shortened life expectancy.

The rising number of natural cause deaths behind bars points to the need for some clear public policy direction. Today, the oldest inmate serving a sentence in a federal prison is 88 years old. 630 or so inmates are age 65 or older. Another 265 inmates are age 70 years or more. Few, if any, of these offenders would likely to be deemed to pose an active or ongoing risk to public safety. Yet many of these aging offenders are, or will become, chronically ill during the course of their incarceration; some will require palliation and die from naturally attributed causes. As many of these older inmates are also lifers,' they will all live out their natural lives still under sentence regardless of whether they are incarcerated or paroled to the community.

As prison health care costs rise under strain to manage complex and chronic illness, it may be time to more seriously consider measures being adopted in other jurisdictions, which are also struggling to keep pace with the rising numbers and costs of keeping an aging population locked up. In the United States, for example, some jurisdictions have introduced medical parole provisions, which allows an inmate with a short life expectancy or who is deemed to no longer pose a threat to society to be paroled to the community. The US Bureau of Prisons now permits offenders over the age of 65 with chronic or serious health conditions and who have served at least half of their sentence to apply for early release. Individuals who meet the age requirement, but who are not afflicted with a life-ending condition can also apply, provided they have served at least 10 years or 75% of their sentence.

The movement to expand release options for older inmates who pose little or no substantive risk to public safety not only makes economic sense; it is also validated by research which shows criminal risk declines significantly as people age. We should use this knowledge to inform better public policy responses to aging and crime. For example, I would suggest that escape risk is not an entirely valid, proportionate or necessary reason for keeping a 60 or 70-year old locked up in a medium security facility.

CSC needs to enhance partnerships with outside service providers, including arrangements that would allow a critically ill inmate to serve out his or her sentence in a long-term care or hospice setting. Better utilization of parole by exception' provisions is also required. It is unacceptable that a terminally ill offender would die behind bars simply because case workers were unwilling or unable to go through the administrative steps necessary for bringing the case to a hearing before the Parole Board. At an annual average incarceration cost of than $108,000, surely it is time to explore alternative community options that are safe, appropriate and cost-effective.

The concepts of dignity and decency should inform efforts going forward. For both justice and cost reasons, federal corrections requires viable, responsive and effective alternatives to incarceration for elderly and geriatric offenders. Other jurisdictions are leading the way Canada has some catch up to do.

8. I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety request that the Public Safety and National Security Committee (SECU) of parliament conduct a study and public hearings into policy options for managing the care, custody and safe release of inmates aged 65 and over who no longer pose an ongoing substantiated risk to public safety.

3. Conditions of Confinement

Special Focus on Administrative Segregation

Issues in Focus

What is Administrative Segregation?

- Section 31 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act ( CCRA ) states that the purpose of administrative segregation is to maintain the security of the penitentiary or the safety of any person by not allowing an inmate to associate with other inmates.

- Effectively a prison within the prison, Canadian law and policy allows for the use of administrative segregation for the shortest period of time necessary, in limited circumstances and only when there are no other reasonable or safe alternatives.

- Administrative segregation is not intended to be used as a form of punishment.

- There are no legal limits on how long an inmate can be held in administrative segregation, though there are mandated procedural reviews that take place at the 5, 30, and 60 day marks. A handful of inmates have been held in perpetual, long-term or indefinite segregation, in some cases lasting years.

- Many terms, such as administrative segregation, dissociation, isolation, seclusion, protective custody and solitary confinement are used, often interchangeably, to describe the segregation experience. These terms encompass a range of conditions of detention, but they share some common elements e.g. restrictions on freedoms of association, assembly and movement and they imply some degree of perceptual and sensory deprivation as well as social isolation. The generally accepted term that captures these common elements, including administrative segregation, is solitary confinement.

- In A Sourcebook on Solitary Confinement , Dr. Sharon Shalev (2008), a leading international authority on solitary confinement, states:

Solitary confinement is defined as a form of confinement where prisoners spend 22 to 24 hours a day alone in their cell in separation from each other. Notwithstanding the different meanings attached to each of these terms in different jurisdictions, the term solitary confinement' is used interchangeably with the terms isolation' and segregation' when describing regimes where prisoners do not have contact with one another, other than, as is the case in some jurisdictions, during an outdoor exercise period.

- In the Canadian federal context, the term administrative segregation falls well within the spectrum of restrictive environments captured by the definition of solitary confinement. Administrative segregation involves social separation, seclusion and isolation of an inmate in a sensory depriving environment.

- In practice, segregated inmates spend 23 hours a day alone in their cells (furnished with a bed and a toilet no table or chair). The segregated inmate eats all meals alone in the cell, is permitted to take an hour of outdoor exercise per day (weather permitting and with other compatible inmates if possible),

is given the opportunity to shower every second day and has limited access to the phone. - Offenders who are segregated for more than a week are normally permitted to have some of their personal effects, including TV sets.

- The majority of interactions with correctional staff, nurses and psychologists are conducted through the food slot of the segregation cell door. The Canadian experience is such that segregated inmates have very few meaningful human or social contacts.

- According to Dr. Shalev, between one-third and 90% of prisoners experience some negative impacts of long-term solitary confinement. The symptoms may include insomnia, confusion, feelings of hopelessness and despair, distorted perceptions and hallucinations.

For more than 20 years, the Office has extensively documented the fact that administrative segregation is overused. With an average daily inmate population of just over 14,500 the CSC made 8,300 placements in administrative segregation in 2014-15. On April 1, 2014, there were 749 offenders in administrative segregation. There is no escaping the fact that administrative segregation has become the most commonly used population management tool to address tensions and conflicts in federal correctional facilities. During the reporting period, 27% of the inmate population experienced at least one placement in administrative segregation. It is so overused that nearly half (48%) of the current inmate population has experienced segregation at least once during their present sentence.

Administrative segregation is also commonly used to manage mentally ill offenders, self-injurious offenders and those at risk of suicide. Inmates in administrative segregation are twice more likely to have a history of self-injury and attempted suicide, and 31% more likely to have a mental health issue. 68% of inmates at the Regional Treatment Centres (designated psychiatric hospitals) have a history of administrative segregation, further evidence that the CSC uses segregation to manage behaviours associated with mental illness.

The over-reliance on segregation is not uniform; certain incarcerated groups are more affected than others, including federally sentenced women with mental health issues, Aboriginal and Black inmates. Aboriginal inmates continue to have the longest average stay in segregation compared to any other group.

In 1992, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act ( CCRA ) incorporated key procedural safeguards to govern the use of administrative segregation in federal corrections. These legal provisions include:

- Release from administrative segregation at the earliest appropriate time.

- Reasonable alternatives to administrative segregation must first be explored and exhausted.

- Inmates in administrative segregation have the same rights as those in the general inmate population, except those that cannot be exercised due to limitations specific to administrative segregation or security requirements.

- The CSC shall take into consideration an offender's state of health and health care needs in all administrative segregation decisions.

Issues in Focus

Administrative Segregation and Canada's International Obligations

- The International Convention on Political Rights (ratified by Canada in 1976) states that no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. The UN Human Rights Committee stated in 1994 that prolonged solitary confinement may amount to prohibited acts of torture.

- The Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (ratified by Canada in 2010) stipulates that on the issue of solitary confinement it should never be used on a person with disability, in particular with a psychosocial disability or if there is danger for the person's health in general.

- The Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (ratified by Canada 1977) states that punishment by close confinement or reduction of diet shall never be inflicted unless the medical officer has examined the prisoner and certified in writing that he is fit to sustain it.

- The Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners (1990) requires that efforts addressed to the abolition of solitary confinement as a punishment, or to the restriction of its use, should be encouraged.

- The UN Special Rapporteur of the Human Rights Council on Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (2011) concluded that:

- Solitary confinement is contrary to the rehabilitation and reintegration aims of the penitentiary system.

- Solitary confinement in excess of 15 days should be prohibited.

- Solitary confinement of persons with known mental disabilities of any duration is cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.

- The World Health Organization ( WHO Europe) published in 2014 a report entitled Prison and Health. It finds:

- Solitary confinement has a negative impact on the health and well-being of those subjected to it, especially for a prolonged time.

- Those with pre-existing mental illness are particularly vulnerable to the effects of solitary confinement.

- Solitary confinement can affect rehabilitation efforts and former prisoners' chances of successful reintegration into society following their release.

- International human rights law requires that the use of solitary confinement must be kept to a minimum, reserved for the few cases where it is absolutely necessary, and that it should be used for as short a time as possible.

Unfortunately, unlike the legal provisions that guide disciplinary segregation, the CSC is solely responsible for placing and maintaining offenders in administrative segregation and for complying with the above standards. Maintaining that it needs administrative segregation to safely manage its institutions, the CSC has resisted nearly every call to reform or limit its use or introduce some form of external oversight. In the last ten years, the Office has made 31 separate recommendations to strengthen the administrative segregation governance and accountability framework including:

- Independent adjudication of administrative segregation placements

- Enhanced due process

- Prohibit segregation for those who are seriously mentally ill, self-injurious or suicidal

- Disallow indefinite segregation

- Create alternatives (intermediate mental health care units) to segregation to meet least restrictive criteria

- Prohibit double-bunking (placing of two inmates in a cell designed for one) in administrative segregation

- Develop alternatives to reduce use of segregation for younger offenders.

- Eliminate points of suspension in segregation cells.

Over the years, CSC has accepted a few recommendations regarding staff training and it has made minor administrative policy changes to the segregation framework. It is now moving forward with the creation of intermediate mental health care capacity, which may provide some much-need alternatives to administrative segregation for inmates with mental health issues. However, CSC has consistently and repeatedly rejected any call to strengthen oversight and accountability deficiencies.

Most recently, in its December 2014 response to the Ashley Smith inquest, the Service stated that it could not fully support several aspects of the jury's ten recommendations that would place restraints on its use of segregation and seclusion without causing undue risk to the safe management of the federal correctional system. Although it accepted that administrative segregation is generally not conducive to healthy living, CSC specifically rejected core jury recommendations calling for:

- Abolishment of indefinite solitary confinement.

- Prohibition on placements in conditions of long-term segregation, clinical seclusion, isolation or observation.

- Restriction on the use of segregation and seclusion to 15 consecutive days, in accordance with international standards.

- Prohibition on segregation for more than 60 days per year.

In its response, CSC noted that it is currently engaged in a Segregation Renewal Strategy that will ostensibly reduce the length and number of segregation placements, prevent unwarranted admissions and motivate offenders for release from segregation when risk can no longer be substantiated. According to the Service, this strategy is intended to reframe the thinking about how segregation is used in CSC and strengthen oversight and decision-making. The goal of the strategy is to reduce the reliance on segregation by creating better options and finding more innovative alternatives for safe reintegration. To this end, as the Service indicated in its response to the Ashley Smith inquest, the Minister intends to propose a number of regulatory amendments dealing with administrative segregation that relate to offenders with mental health disorders. CSC has committed to amend its policy framework to reflect the intent of these regulatory changes during the first quarter of 2015. I encourage the Service and Minister to make this work a priority.

Issues in Focus

Key Facts and Trends in Administrative Segregation Today

As of March 2015

- 48% of the current incarcerated population has a history of segregation.

- 26% of all male inmates were admitted to segregation at least once in fiscal year 2014-15, compared

to 25% of federally sentenced women inmates. - The average length of stay in administrative segregation today is 27 days (down from 40 days

ten years ago). - Aboriginal and black inmates are over-represented in segregation. One-third of Aboriginal inmates were segregated at least once during 2014-15. Aboriginal inmates also have the longest average

stays in segregation. - Of the 659 inmates in segregation today, 13.7% have a history of self-injurious behaviour. Of all federal inmates with a history of self-injury, more than 85% also have a history of segregation placement.

- Inmates with a history of segregation are more likely to be assessed as high risk, high needs, low motivation, low reintegration potential and low accountability.

- Inmates with a segregation history are more likely to have behavioural, mental health and/or cognitive issues requiring interventions.

- Over 20% of those inmates who have a history of segregation have also been in a Regional Treatment Centre (psychiatric hospital).

- More than two-thirds of current inmates who have been in a treatment centre have also been in segregation. For women inmates, the ratio is 78.9% and 72.9% for Aboriginal inmates.

One of the most disturbing elements in the evolving administrative segregation framework is that it is used as a punitive measure to circumvent the more onerous due process requirements of the disciplinary segregation system. For the reporting period, there were only 209 placements in disciplinary segregation (or 2.5% of the total segregation placements) compared to 8,309 placements in administrative segregation. The disparity in procedural safeguards between administrative and disciplinary segregation helps explain the discrepancy. Disciplinary segregation has significant procedural safeguards, including sharing information with offenders, holding hearings before an external Independent Chair Person ( ICP ) and meeting a higher burden of proof (beyond reasonable doubt). Although there are procedural safeguards for administrative segregation, these are internally administered by the CSC . Disciplinary segregation also has an upper maximum limit of 30 days whereas administrative segregation does not. In fact, the average length of stay in administrative segregation is more than twice that of disciplinary segregation.

The CCRA stipulates that CSC must rely upon the disciplinary process to address minor and serious disciplinary infractions. However, it appears that circumventing the disciplinary process to isolate, contain, separate, control, manage or even punish has become common. It is easier to deal with tensions and conflicts by placing an offender in administrative segregation than to lay formal disciplinary charges and face the prospect of a hearing before an external ICP .

There is also little doubt that administrative segregation is viewed by those who suffer from mental illness as punitive. In September 2013, the Office released an investigative report that looked at federally-sentenced women who chronically self-injured in prison ( Risky Business ). The women reported to the Office that they saw no difference between administrative segregation, disciplinary segregation, suicide watch or clinical isolation or seclusion. They perceived these placements, regardless of their name or purpose, as punishment for their self-injurious behaviour. Further, as the Office's prison suicide investigation noted, segregation was found to be an independent factor that elevated the risk of suicide.