June 26, 2024

The Honourable Dominic LeBlanc

Minister of Public Safety, Democratic Institutions and Intergovernmental Affairs

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 51st Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigator's Message

Risk Assessment and Classification with Indigenous Peoples since Ewert v. Canada (2018)

The Offender Complaint and Grievance Process

An Investigation of Quality of Care Reviews for Natural Cause Deaths in Federal Custody

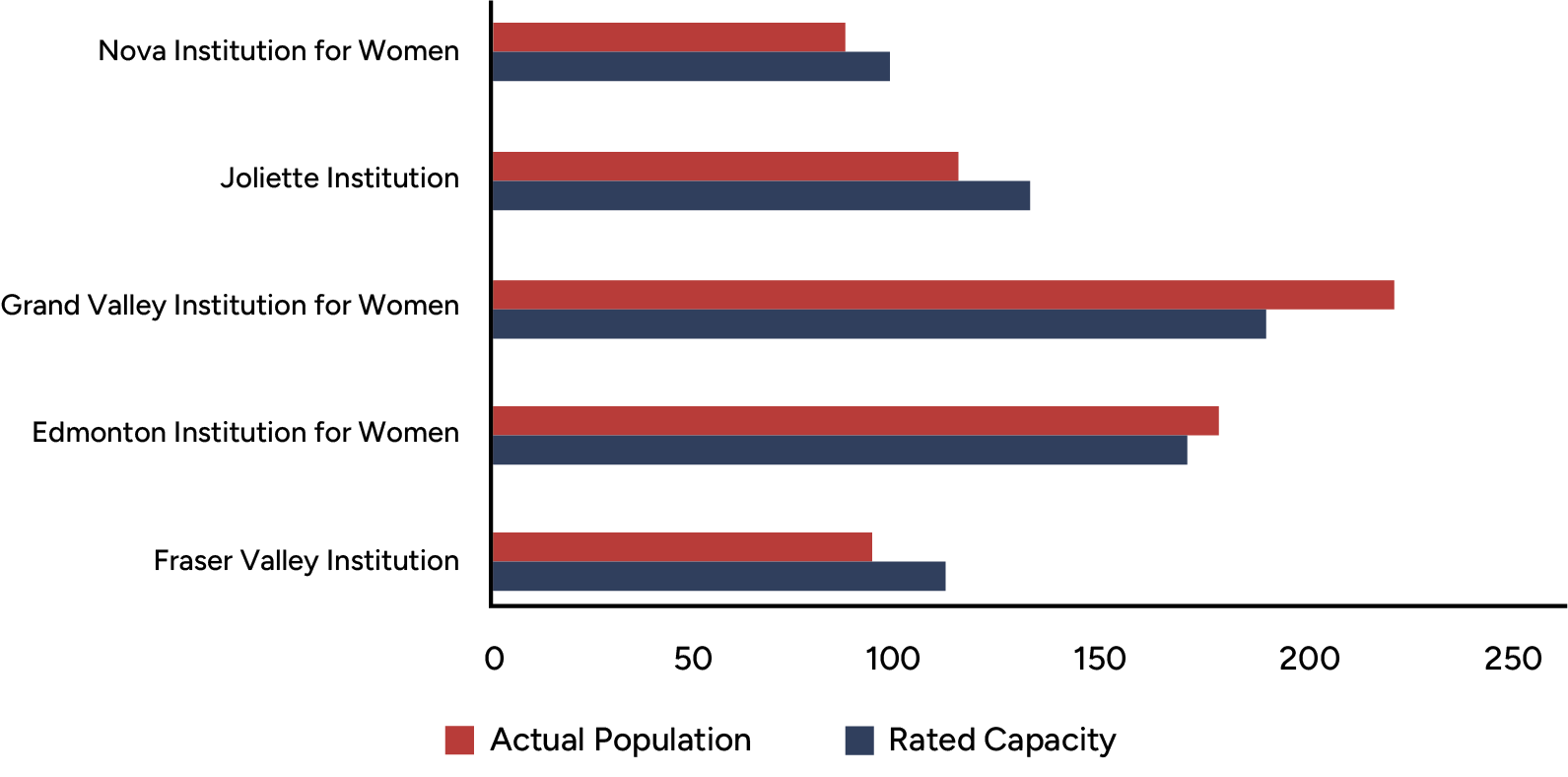

Population Pressures in Women’s Institutions: Overreliance and Impacts of Interregional Transfers

Promising Practices in Indigenous Corrections

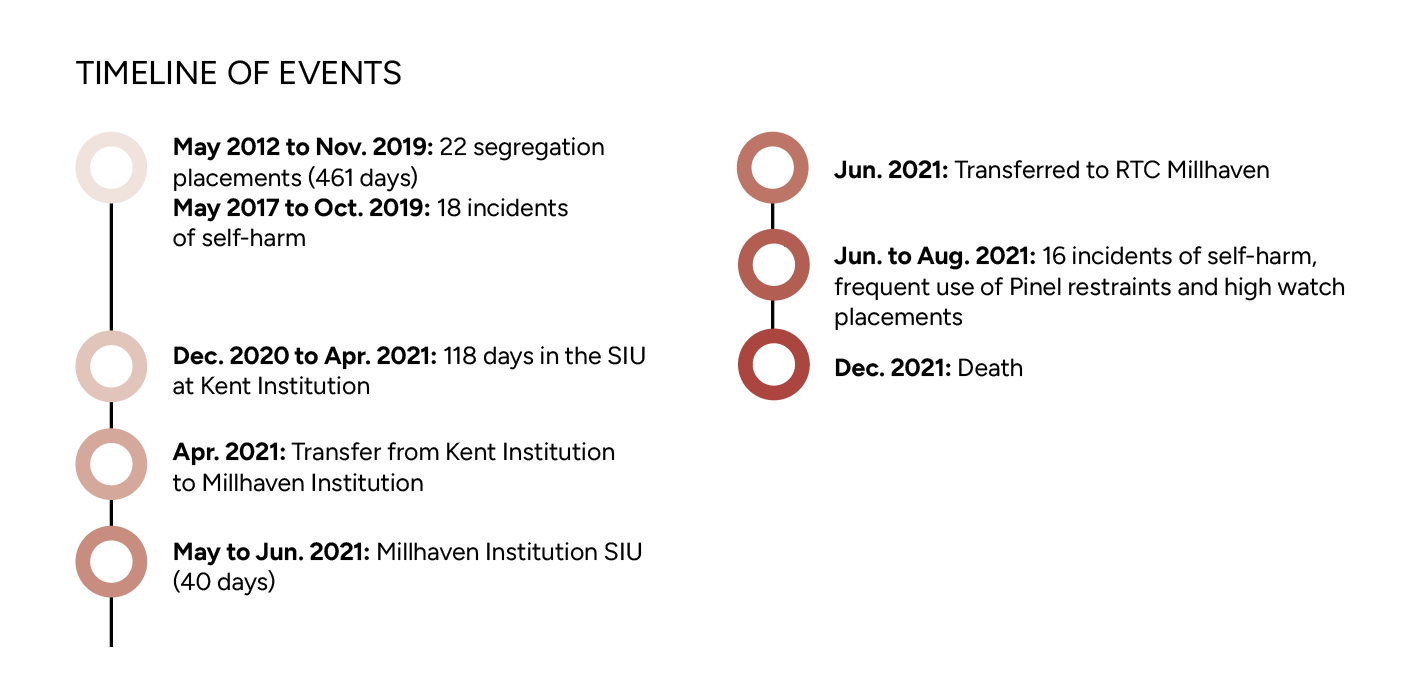

CASE STUDY: Death at the Regional Treatment Centre – Millhaven

National Systemic Investigations

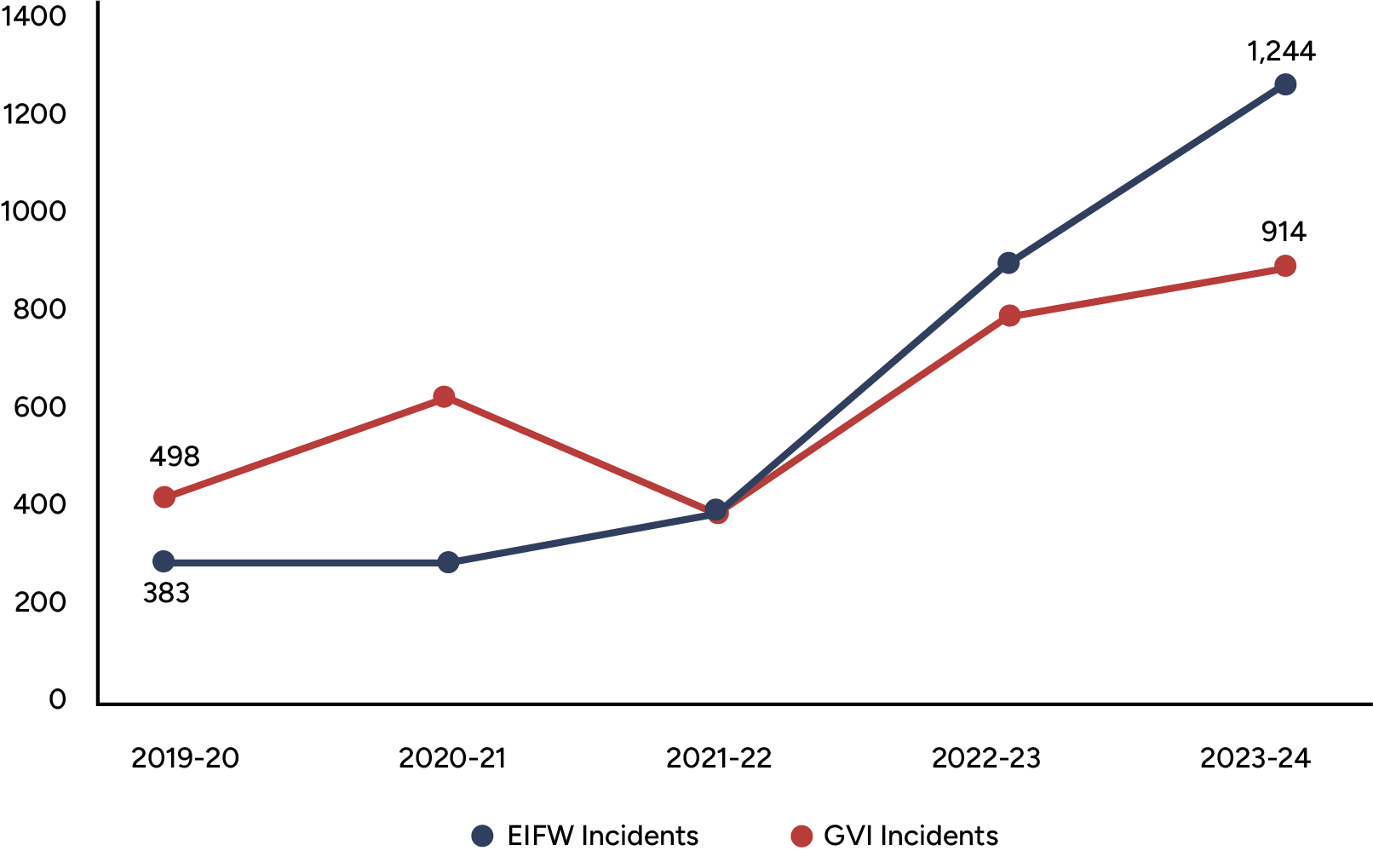

An Investigation of the Standalone Male Maximum-Security Penitentiaries in Federal Corrections

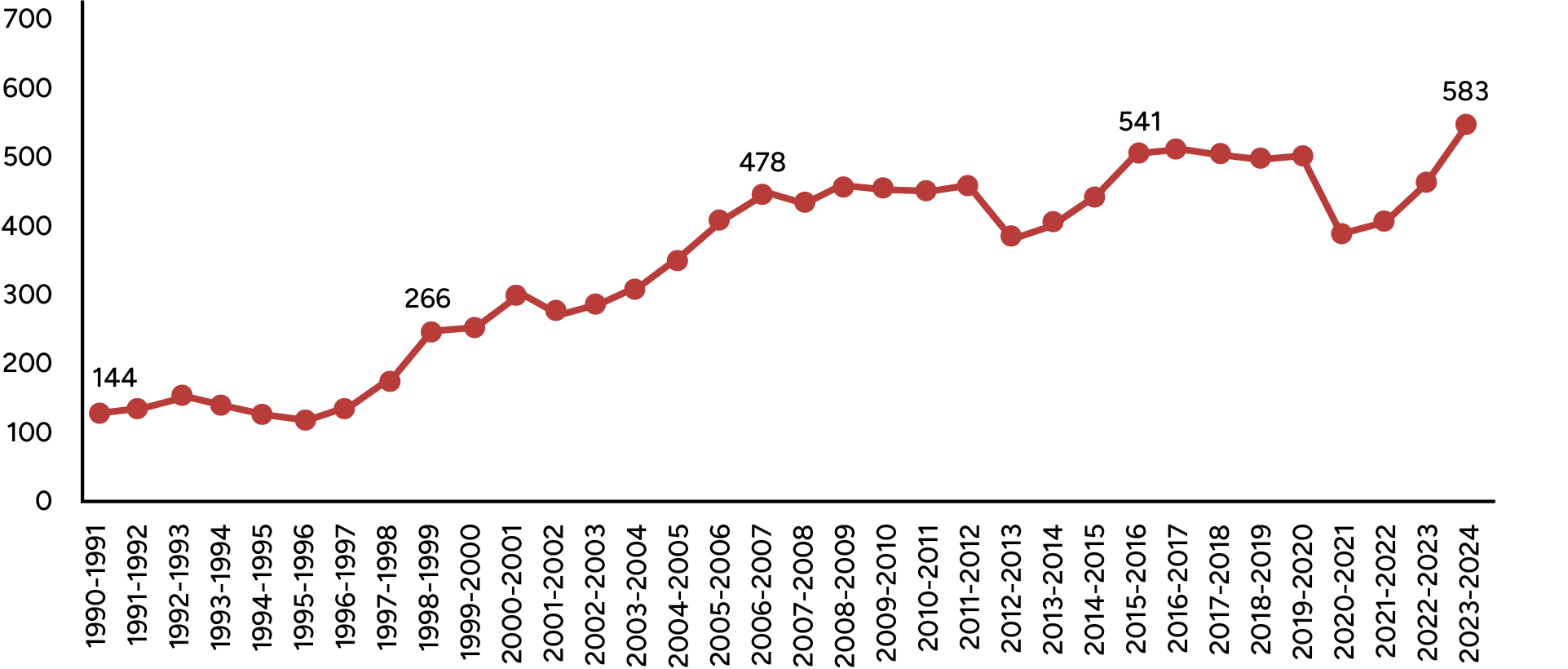

Hope Behind Bars: Managing Life Sentences in Federal Custody

Correctional Investigator’s Outlook for 2024-25

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

ANNEX A: Summary of Recommendations

Response to the 51st Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator

Correctional Investigator's Message

Each year, the production of my Annual Report and the drafting of my introductory message provides an opportunity to reflect on the mandate and work of my Office, which serves as the ombuds for federally sentenced individuals and the external oversight body to Canada’s federal correctional authority, the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC). Our daily work involves conducting regular visits to and inspections of federal penitentiaries, meeting with CSC staff and federally sentenced individuals, and investigating and resolving issues and complaints of prisoners, individually and collectively. We review use of force incidents in federal prisons, as well as deaths in custody and other serious incidents. Our interventions help to ensure federal sentences are managed in compliance with domestic and international human rights standards providing for safe, humane, and lawful custody.

As Correctional Investigator my focus and priority has been to identify, investigate and report on issues of national or systemic significance. This year’s report includes findings and recommendations from two national-level investigations – the management of life sentences and a comparative review of the six standalone male maximum-security institutions. Both investigations break new ground for the Office: it is the first time that the Office has substantively reported on “Lifers” and the investigation of the standalone maximum-security institutions represents the first time that we have conducted a systemwide inspection and review of conditions of maximum-security confinement.

Our findings in these two areas cut to the very core of correctional intent and purpose by exploring what an indefinite sentence can mean in practice (a sentence that only expires upon death), or what purpose maximum-security confinement serves when the legislated goals of rehabilitation and reintegration are not being adequately met. On their own, each investigation raises tough public policy questions that go to the costs and consequences of sentences that are, by any measure, exceedingly long (as with Lifers), expensive and excessively harsh (as with maximum-security prisons).

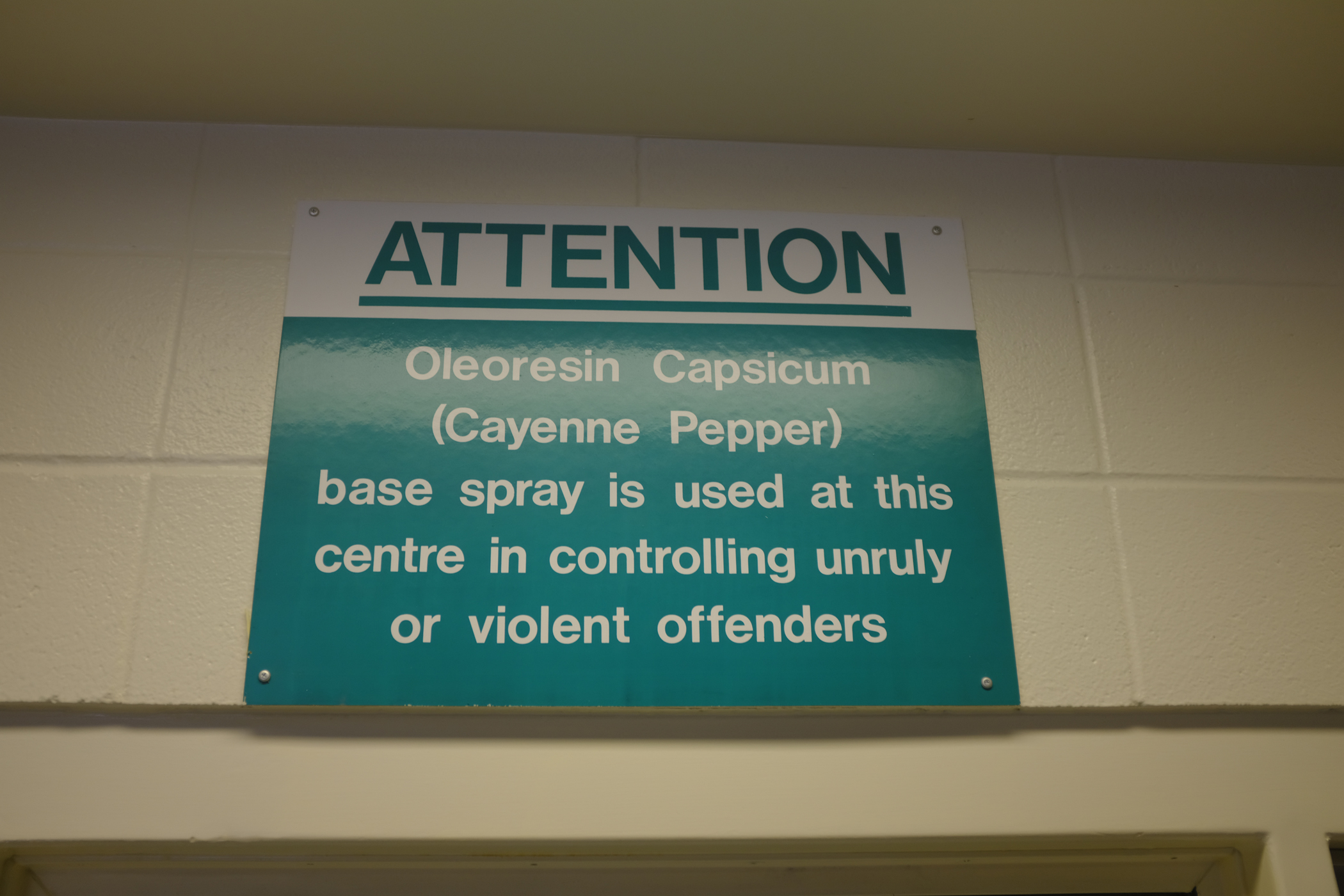

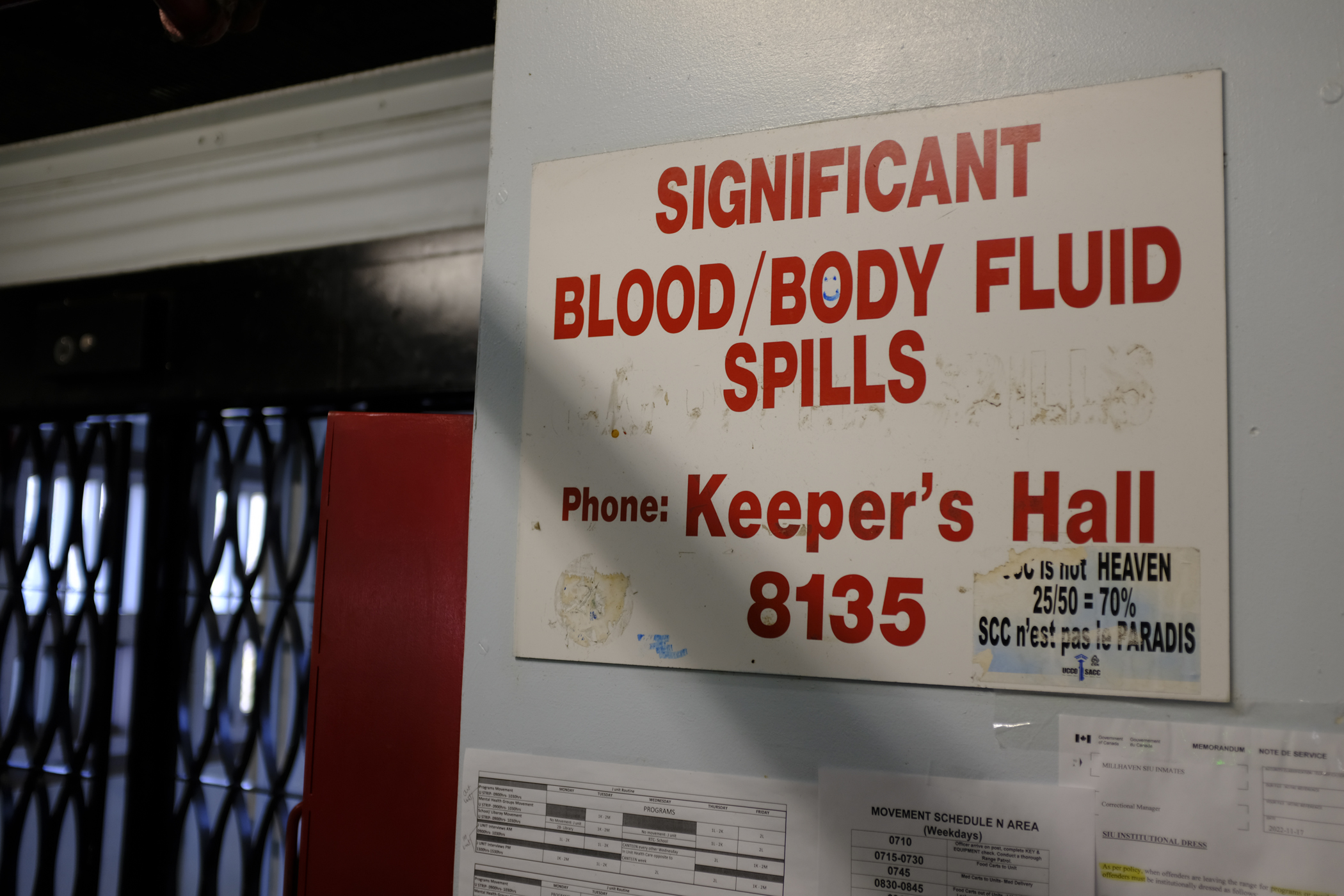

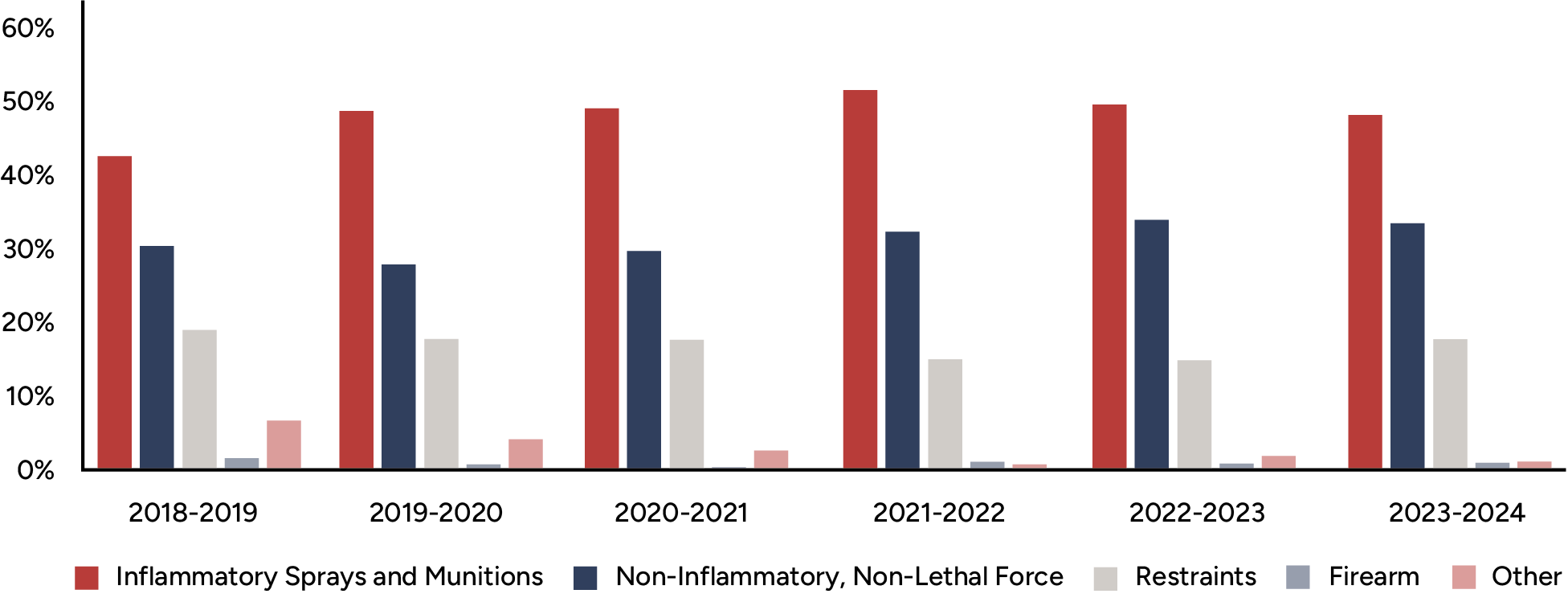

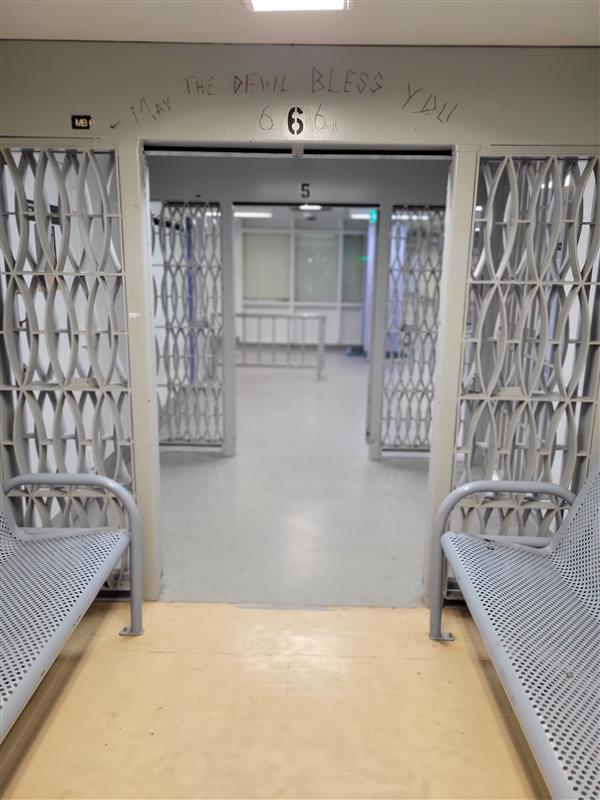

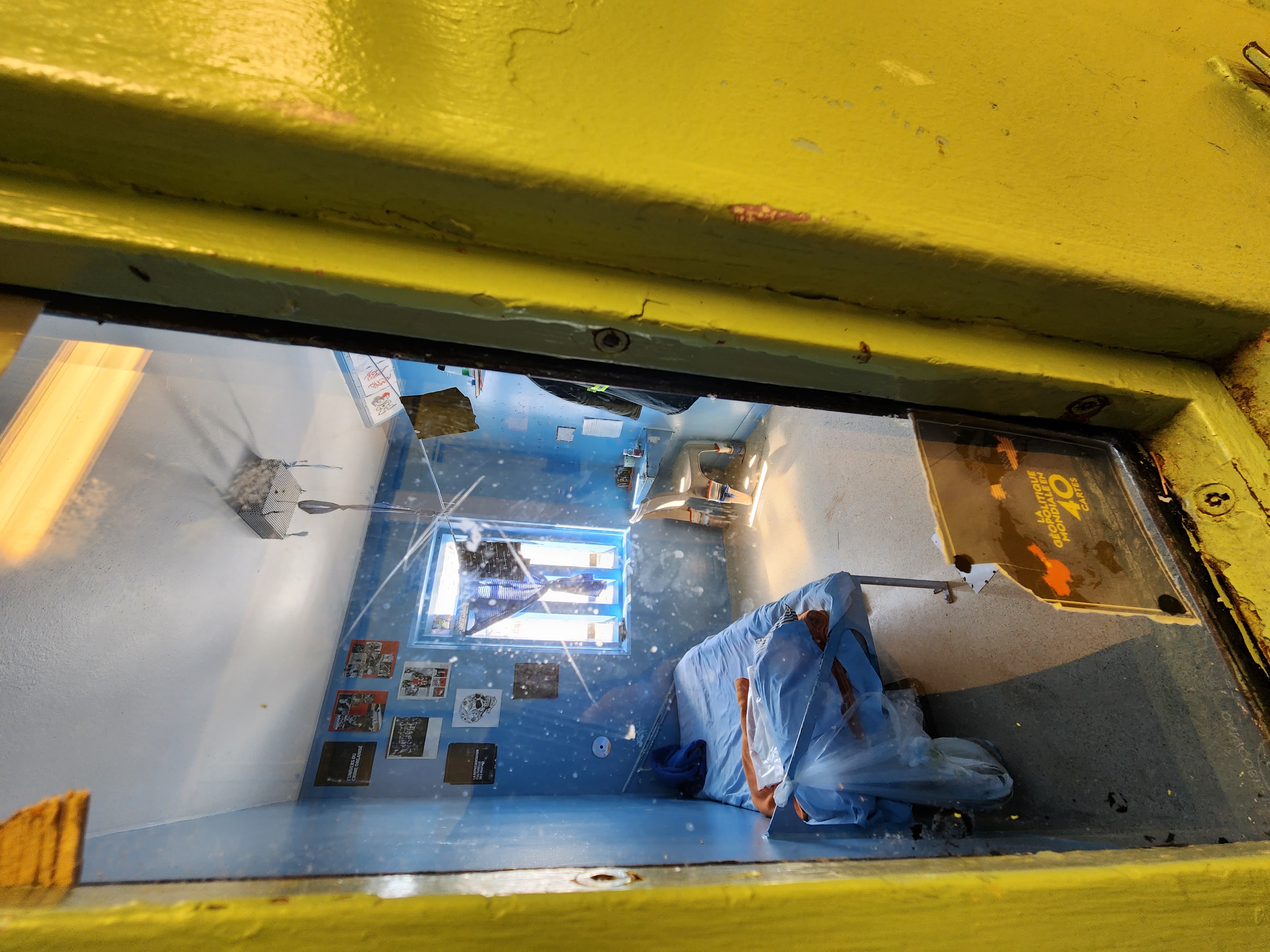

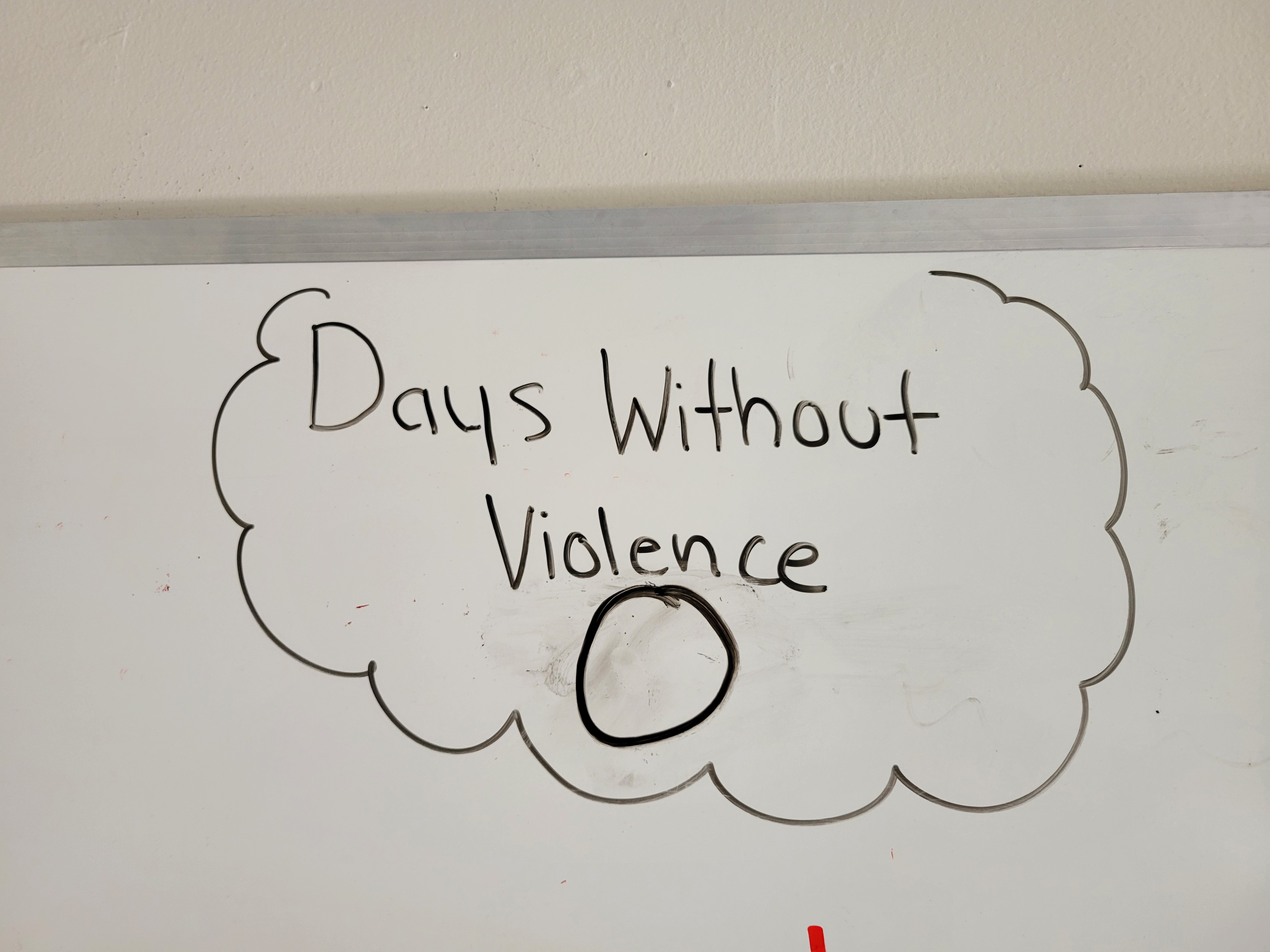

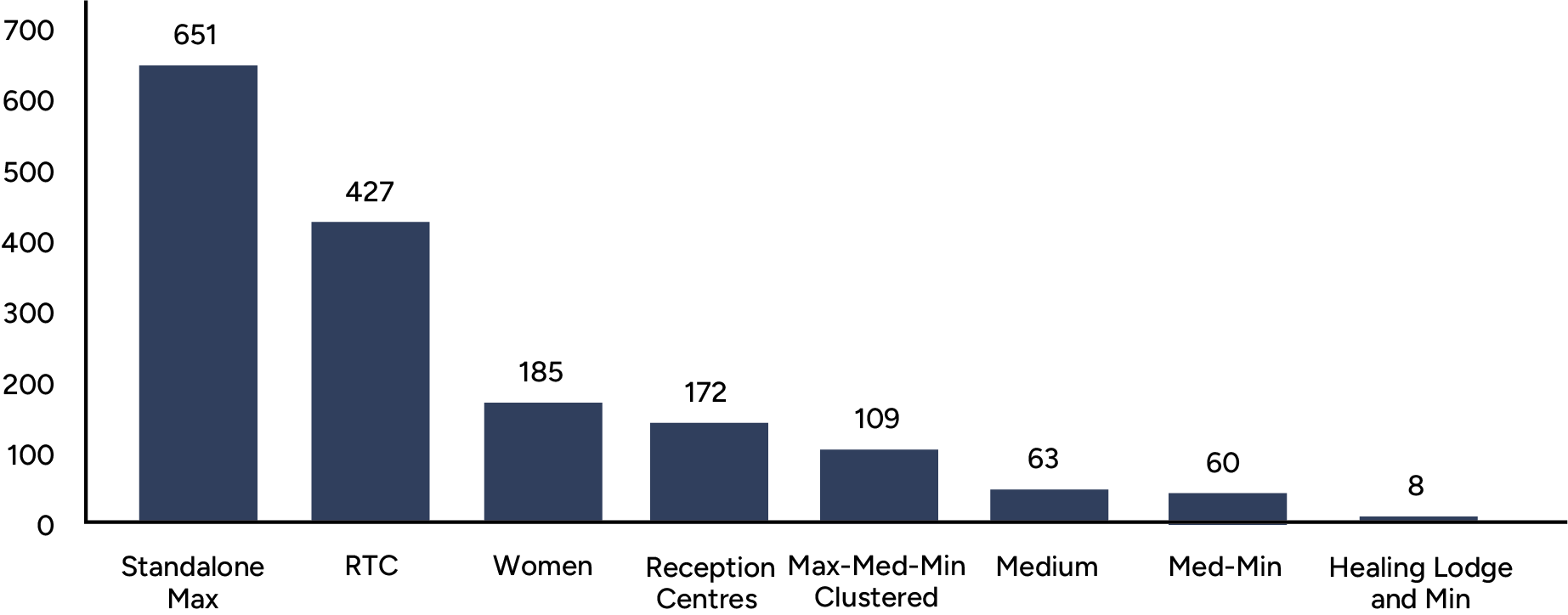

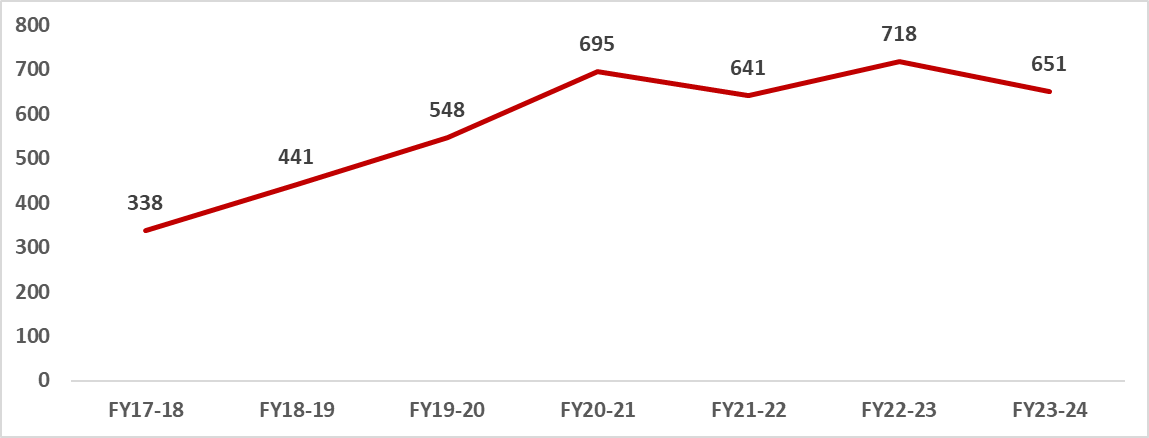

With respect to our investigation of maximum-security institutions, we found that the Correctional Service of Canada lacks a clearly articulated statement of purpose for what maximum-security confinement is intended to achieve. We observed operational practices and conditions that were so punitive and restrictive that they seemed antithetical to any stated correctional intent, principle or outcome. Of significant concern, we found that use of force incidents in standalone maximum-security institutions now account for 46% of all uses of force nationwide, though these facilities house approximately 10% of the total in-custody population.

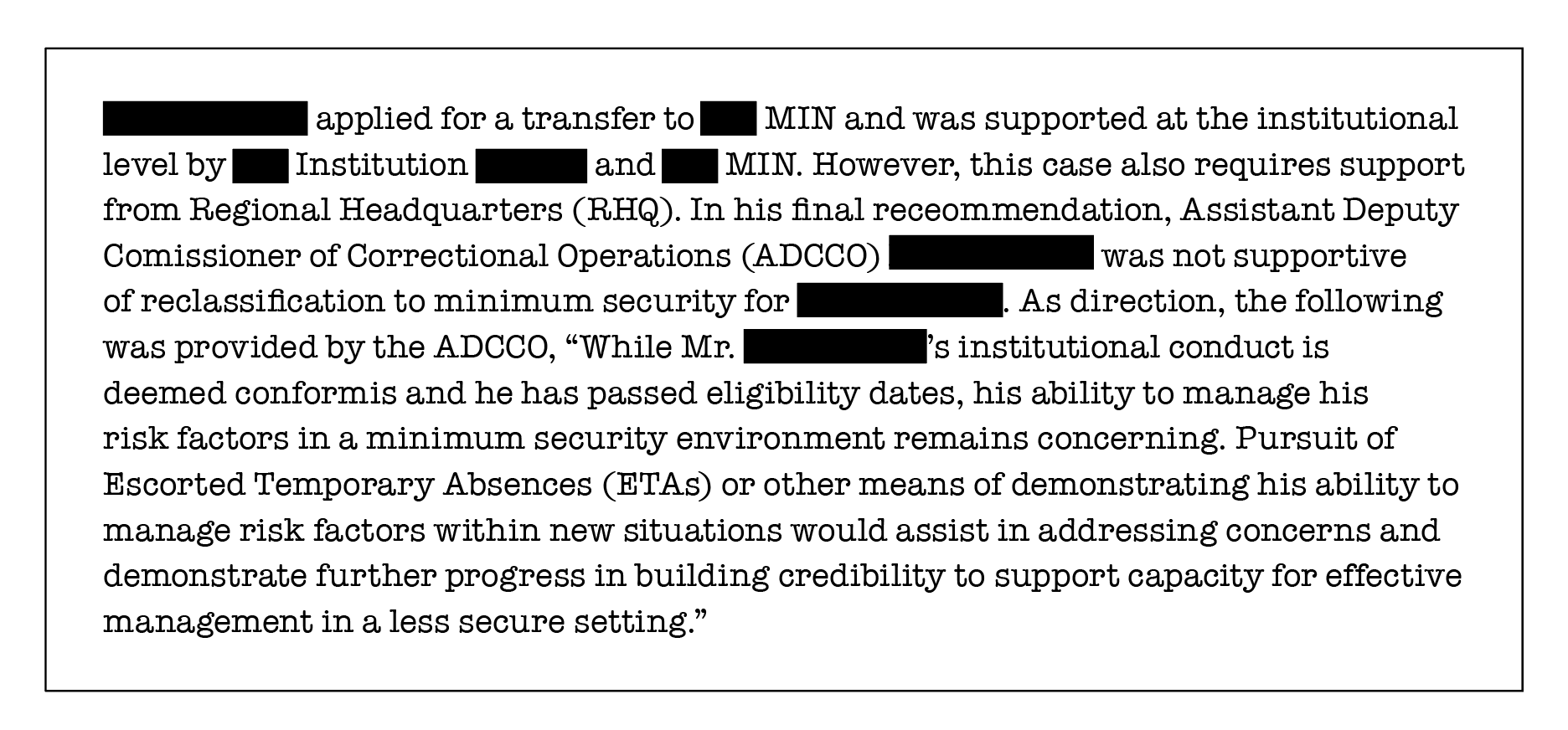

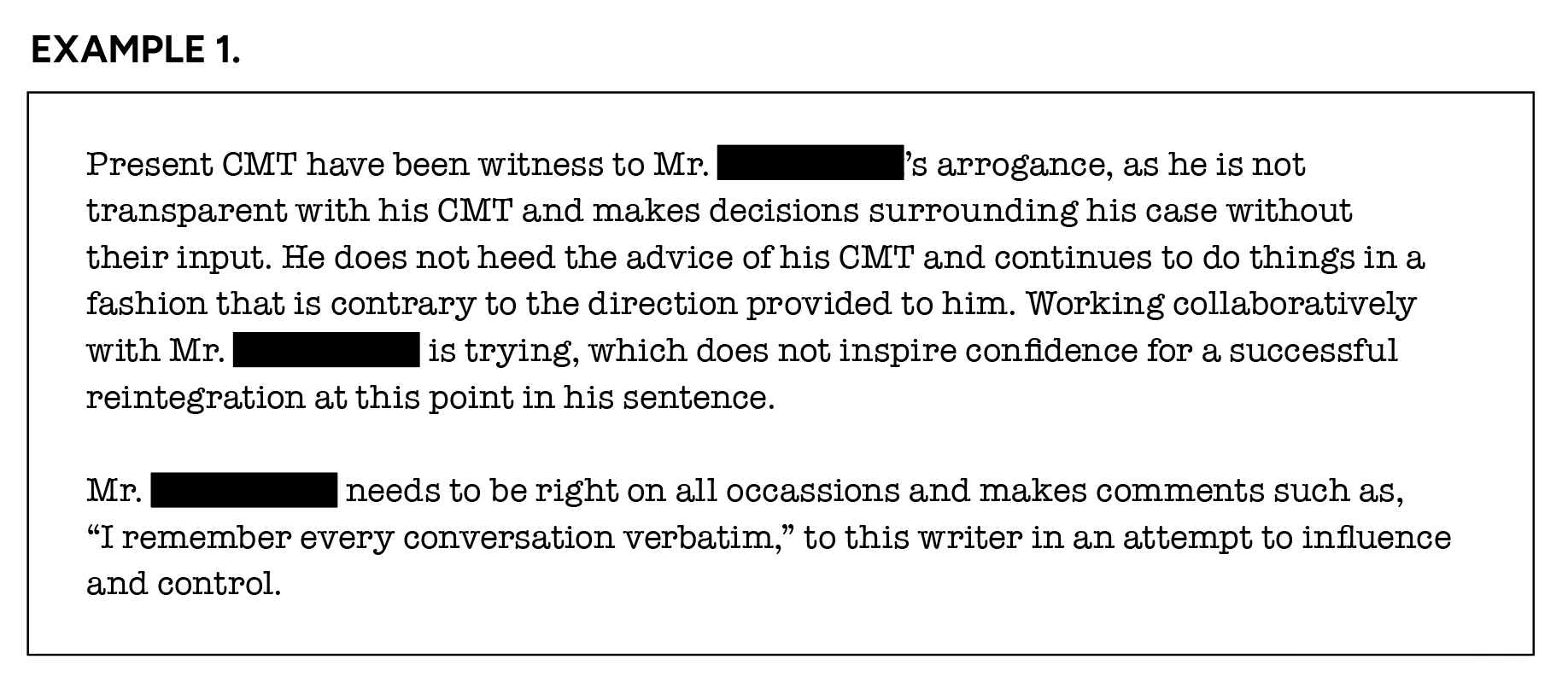

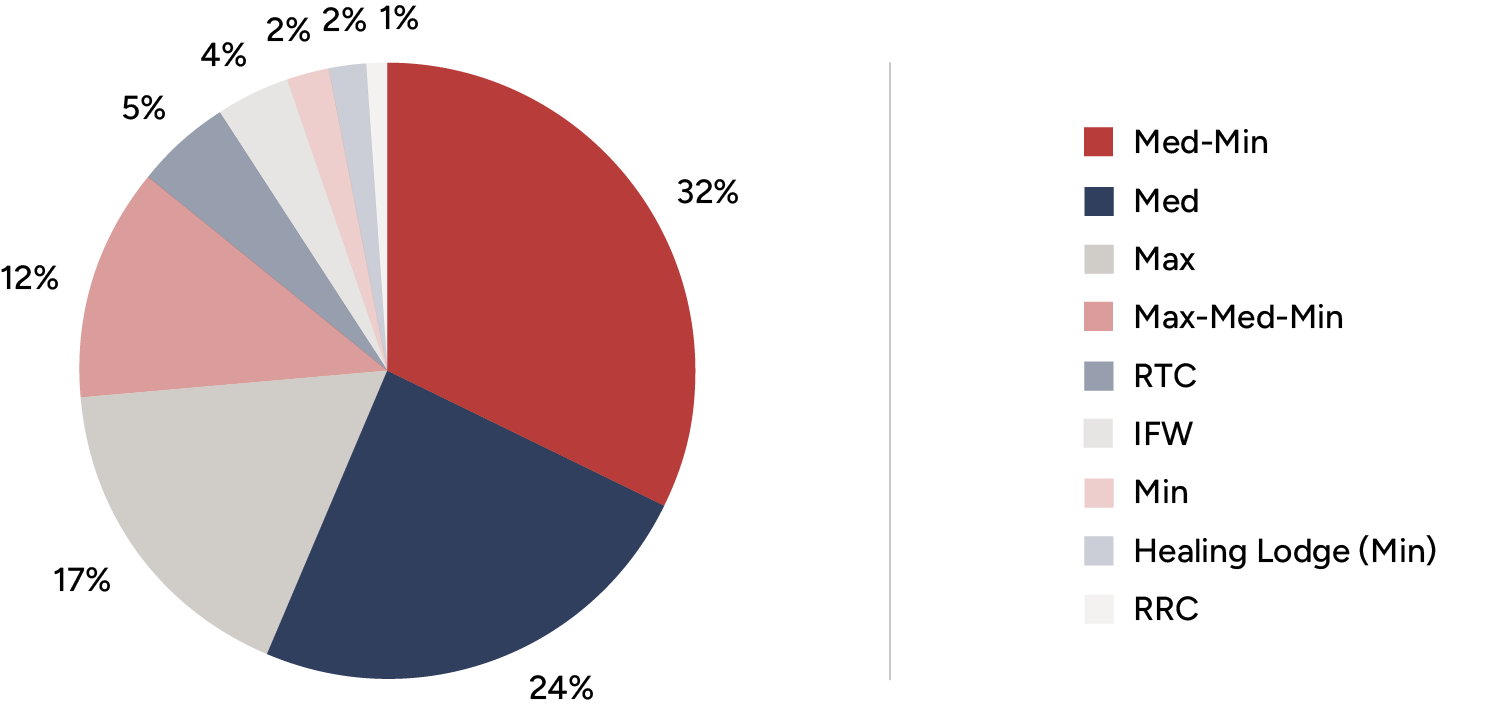

In our Lifers investigation, we encountered persons serving indeterminate sentences who meet all their program requirements but who often find themselves languishing in medium-security facilities long after their parole eligibility dates have expired. We found that lifers are kept at higher security levels for longer periods with no clear rehabilitative or reintegrative purpose. To different degrees, both the life-sentenced and maximum-security prisoner experience an unacceptable amount of wasted or idled time that serves little rehabilitative or reintegrative interest.

Policy-makers need to take heed of what happens to imprisoned people when prospects for release or cascading down security levels are arbitrarily delayed or indefinitely denied, or when excessive cellular confinement all too predictably leads to violence. As research has long confirmed, longer or harsher sentences are statistically co-related with an increase in more reoffending, not less. To serve a more constructive and redeeming purpose than punishment or retribution, which in any case are no longer part of the purpose or principles of the contemporary sentencing regime in Canada, correctional practice must offer up more than the nature and gravity of the offence and the degree of responsibility of the offender. The conclusion that I draw from these two very different investigations is that imprisonment without purpose or end is cruel, arbitrary, and unlawful.

My report also includes several important national policy updates. This year’s collection includes, among others, a compliance review of CSC’s internal complaints and grievances system, an update on population pressures in women’s corrections, an investigation of CSC’s quality of care reviews into natural causes of deaths in custody, and an assessment of CSC’s (in)actions six years after the seminal Supreme Court of Canada decision in Ewert v. Canada found that a number of assessment tools used by CSC violate the law when applied to Indigenous peoples. Finally, the Office’s investigation into a death at one of the five Regional Treatment Centres, which are accredited psychiatric or mental health hospitals staffed and run by CSC, raises significant concern about the operation and governance of these facilities, particularly the scope and degree of clinical practice in providing safe, effective, and unfettered patient care within co-located penitentiary settings.

Beyond systemic investigations, national policy updates, prison inspections and best practice reviews, there are other issues and concerns that occupied our attention in 2023-24. Unexpectedly, there was an unusual number of decisions impacting federal corrections that seemed to lack adequate consultation, engagement, or notice to my Office. For example, buried deep in the federal budget tabled in April 2024 was a proposal to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act to allow for “high-risk” migrants to be detained in federal penitentiaries. This reference caught my Office and most other human rights advocates unaware. The proposed expansion of immigration detention into federal prisons on grounds of alleged public safety risk is a draconian measure, a dereliction of Canada’s responsibility to provide safe haven to migrants and refugees fleeing persecution or war, or simply those seeking to live a better life. I acknowledge that there may be a few foreign nationals who may present to border enforcement or immigration authorities as a flight risk, but to detain them in a federal penitentiary seems unwise, excessive, and contrary to Canadian values. There must be more humane and compassionate alternatives.

Similarly, other decisions taken by the CSC during the reporting period also seemed to be lacking in responsiveness or consultation with my Office. One example includes technical amendments and repromulgation of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) guidelines that occurred without notice or consultation. Significantly, the Government of Canada still allows for this procedure to be carried out in a federal penitentiary, under “exceptional” circumstances (“patient’s” request). Equally, the decision to staff Patient Advocate positions with CSC employees rather than external and independent appointees sends a very mixed and distorted message, inside and outside the organization. I have long anticipated this unfortunate outcome, which prompted my decision to elevate my concerns to the attention of the Minister of Public Safety in my last Annual Report. At any rate, this decision moves in a direction that is contrary to other complementary provisions enacted at the same time as Patient Advocacy Services were adopted, and which serve to protect the clinical independence and professional autonomy of CSC’s health care workers. Simply put, the government and CSC are missing an opportunity to support the provision of essential health care behind bars without undue influence or interference from security staff.

I want to finish this message on a positive and constructive note. In support of the office’s maximum-security investigation, I made a point to visit all the standalone male maximum-security penitentiaries. I was professionally, warmly, and courteously received by the Wardens and members of the management teams at each of the max sites that I visited. I met with many dedicated and exceptional CSC staff members and engaged in several informative exchanges with program facilitators, teachers and frontline staff who related their challenges (and achievements), almost without exception, in a frank, honest and forthright manner. Their jobs are demanding, challenging and complicated and their duties are carried out in the most unusual, difficult, and extraordinary places of human deprivation and trauma. I truly respect what they do, even if I sometimes disagree with how they do it.

Our investigators relate the same experience of being engaged professionally, respectfully, and collegially by CSC staff, often relating to me that their access to staff and prisoners and to all parts of the penitentiary to which they are assigned proceeds efficiently, effectively, and usually without any interference or complication. The date and reason for prison visits are communicated well in advance and staff make appropriate arrangements to accommodate the smooth and efficient conduct of our business. Cooperation, engagement, and collaboration are part and parcel of prison oversight. Our investigators work hard to establish rapport, trust and confidence with the people who live and work behind prison walls. As a third party, it is how we get results in the complaints resolution business.

Unfortunately, the same degree of collaboration and cooperation is not always reciprocated when my staff approach National Headquarters to meet or discuss issues, or request information related to an ongoing investigation. We often experience protracted delays in receiving information and there seems to be a reluctance on the part of the Service to meet, share information or engage with the findings and recommendations of my Office. Rarely do we receive a call from the Office of Primary Interest that would inform, qualify, or clarify our request.

I acknowledge that relationship building and trust can take time with good-faith efforts from both sides. I do not expect warm, close, or friendly relations, as that is not only impractical but likely contrary to ombuds practices and principles of independence, neutrality, and impartiality. However, at the very least, I do expect cooperation at all levels and compliance with sections 172 (right to require information and documents) and 191 (consequences for hindering or obstructing) of the law. We work best when our respective staff members understand and respect our different but complementary roles and responsibilities. After all, our two agencies share the same legislation, we serve a common public safety purpose, we are housed under the same Public Safety Portfolio, we have the same Minister, and we are all employees of the federal public service. We serve government and Canadians, and we ultimately work to advance safe, effective, and humane care and custody.

Ivan Zinger, JD., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

June 2024

Executive Director’s Message

The Office’s focus this year continued to be on creating an effective and efficient independent prison oversight body with the implementation of our multi-year Strategic Plan, supported by an increase in permanent funding. Creating a healthy workplace that is adequately staffed and ensuring the well-being of our employees has been, and continues to be, a priority, as is providing service excellence for the incarcerated individuals we serve. For the first time in recent memory, we have a sustainable number of Early Resolution Officers and Investigators taking live calls from people behind bars, resolving issues of concern, conducting institutional visits, and investigating issues of priority. We have also begun a process of ‘leaning’ our complaints process to find more efficiencies and enable us to focus on more systemic issues. We look forward to seeing and reporting on the results of this exercise next year.

In 2023-24, we created new positions that were desperately needed and finalized our organizational structure to better meet the needs of the people we serve in Canada’s penitentiaries, as well as provide opportunities for career development for our employees. We also expanded our investigative approach by moving from institutional visits with investigators attending prisons alone to developing an inspection model that allows for more of a team approach. This facilitates more in-depth investigations as well as a sharing of the large workload that faces staff on these institutional visits. We have also been able to create more diverse teams with different areas of expertise to conduct our systemic investigations.

Although there remains work to be done to achieve a fully staffed and sustainable structure, we are well on our way. In the last year the Office addressed 4,299 complaints and spent 230 days in institutions where we conducted 1,258 interviews with federally incarcerated persons.

The hard work of our talented employees, our continued work and collaboration with the Correctional Service of Canada and several non-governmental agencies, including Indigenous organizations, reminds us that we are all working to achieve a common outcome – a safe, fair, and humane correctional system that is guided by domestic and international human rights laws and standards. In a country such as Canada, we must continue to strive for and expect better correctional outcomes. This is done not only with grit and determination, but by working together and sometimes thinking outside the box. Our Office is certainly up for the challenge.

Monette Maillet

Executive Director and General Counsel

National Updates

This section summarizes policy issues or significant individual cases raised at the institutional and national levels over the course of the reporting period. The issues and cases presented here were either the subject of discussions with institutional Wardens, an exchange of correspondence, a follow-up from previous Annual Reports, or an agenda item in bilateral meetings involving the Commissioner, myself, and our respective senior management teams. These areas of unresolved, unaddressed, or updated concerns remain under active investigation. Therefore, this section serves to document progress in resolving issues of national significance or concern.

Risk Assessment and Classification with Indigenous Peoples since Ewert v. Canada (2018)

“…it is the responsibility of service providers, correctional agencies, and professional bodies to ensure the responsible application of forensic risk, and any other assessment measures. Such applications should be conducted in a culturally responsive and anti-racist manner to promote decision-making that can maximize benefit and minimize harm for justice-involved persons, enhance community safety, and advocate for human rights and social justice.”

– Olver et al. (2024)Footnote 1

The Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) uses a variety of assessment and classification tools to inform decision-making regarding most aspects of an individual’s sentence. These tools were largely designed to assist decision-makers in estimating the level of risk posed by an individual for problematic or criminal outcomes (e.g., institutional misconduct, recidivism). Today, assessment and classification tools hold a significant amount of weight in guiding and determining the course of one’s sentence, from admission to warrant expiry – including initial placement, security level, referrals to programming, access to services, time spent behind bars, timing and conditions of release, and intensity of community supervision. Given that these tools were developed by and for majority White individuals, in recent years, their validity and reliability when used with diverse populations have been the basis of considerable interest in public policy and academic discourse, as well as in the Canadian courts.

Most notable among these debates was the case of Ewert v. Canada (2018), which made its way through the Federal Courts and eventually to the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC).Footnote2 In this case it was argued that a number of assessment tools used by CSC violate the law and sections of the Charter when applied to Indigenous peoples. Specifically, the complainant in the case, Mr. Ewert – a Métis man serving a federal sentence – argued that psychological and actuarial tools used by CSC have not been properly validated for use with Indigenous peoples and are therefore discriminatory, placing Indigenous peoples in a position of significant disadvantage. Mr. Ewert first raised concerns regarding the validity of assessment tools nearly 25 years ago, when he submitted his initial grievances to CSC on this matter. Fundamental to the arguments made in Mr. Ewert’s case was that the Service’s use of these tools not only violated legal requirements under section 4(g) of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) to “respect ethnic and cultural differences and be responsive to the special needs of Indigenous persons,” but also the requirement set out in section 24(1), requiring that CSC “take all reasonable steps to ensure that any information about an offender that it uses is as accurate, up to date and complete as possible.” Mr. Ewert further argued that the use of these tools infringed upon his Charter rights (under sections 7 and 15).

On June 13, 2018, the SCC rendered its decision on the case, and while the court rejected Mr. Ewert’s arguments regarding violations of his Charter rights, it issued a discretionary remedy in the form of an official declaration, stating that CSC had breached its statutory obligation under s.24(1) of the CCRA. It was determined, contrary to CSC’s position, that the results of actuarial assessments indeed constitute information and therefore, given what the court determined to be a lack of research conducted by the Service to demonstrate the validity of these tools, CSC had failed to take all reasonable steps to ensure information about Mr. Ewert was accurate, as required by law.

While this case focused on the validity of five specific psychological and actuarial toolsFootnote 3, it serves to highlight broader and ongoing issues regarding not only the validity and accuracy of the impugned tools as applied with Indigenous peoples, but the validity, equity, impacts, and applicability of all tools CSC uses to make decisions about an individual’s sentence. In the SCC decision, writing for the majority, Wagner J. raised these very concerns:

“the clear danger posed by the CSC’s continued use of assessment tools that may overestimate the risk posed by Indigenous inmates is that it could unjustifiably contribute to disparities in correctional outcomes in areas in which Indigenous offenders are already disadvantaged.”

To this point, six years after this decision was written, the disparities in outcomes for Indigenous peoples persist and, in some cases, have worsened. Indigenous peoples continue to be vastly over-represented in federal prisons overall (i.e., account for one third of the in-custody population) as well as in higher security levels, serve more of their sentence behind bars, and experience greater delays and barriers in accessing relevant programming. Given that assessment and classification decisions are often the starting point and serve as the basis upon which these decisions are made, it is even more crucial to understand the role these tools play in perpetuating these, among many other, obstacles Indigenous peoples face over the course of their sentence.

Previous Reporting and Recommendations

June 13, 2024, marked six years since the Ewert decision; however, concerns regarding the applicability of assessment and classification tools with Indigenous peoples go back decades. This Office has a long history of raising concerns regarding the quality, accuracy, and impacts of assessment tools. In the last twenty years, the OCI has issued eight public recommendations on assessment and classification practices with Indigenous peoples specifically, calling on the Service to take concrete steps to ensure the tools it uses are valid, reliable, culturally informed in their composition and application, and that the over-classification of Indigenous peoples – Indigenous women in particular – be properly investigated and corrected.

OCI Public Recommendations on Classification and Assessment with Indigenous Peoples

2003/04: the Minister initiate an evaluation of CSCs policies, procedures, and evaluation tools to ensure that existing discriminatory barriers to the timely reintegration of Aboriginal offenders are identified and addressed. This review should be undertaken independent of CSC, with the full support and involvement of Aboriginal organizations, and report by March 31, 2005.

2005/06: in the next year the Correctional Service: implement a security classification process that ends the over-classification of Aboriginal offenders.

2009/10: the Service provide clear and documented demonstration that Gladue principles are considered in decision-making involving the retained of the rights and liberties of Aboriginal offenders in the following areas: segregation placements, access to programming, custody rating scales, penitentiary placements, access to the community, conditional release planning and involuntary transfers.

2012/13: the CSC audit the use of Gladue principles in correctional decision-making affecting significant life and liberty interests of Aboriginal offenders, to include penitentiary placements, security classification, segregation, use of force, health care and conditional release.

2015/16: develop new culturally appropriate and gender specific assessment tools, founded on Gladue principles, to be used with male and female Indigenous offenders.

2018/19: publicly respond to how it intends to address the gaps identified in the Ewert v. Canada decision and ensure that more culturally-responsive indicators (i.e., Indigenous social history factors) of risk/need are incorporated into assessments of risk and need; and, acquire external, independent expertise to conduct empirical research to assess the validity and reliability of all existing risk assessment tools used by CSC to inform decision-making with Indigenous offenders.

2022/23: the Minister direct CSC to work with the Section 81 Healing Lodges to identify the main causes of vacancy rates and identify actions that will be taken to increase and maintain higher occupancy rates, with attention to: Developing new and rigorously validated security classification tools for Indigenous peoples, from the ground up, that reduce their over-representation in medium and maximum security, consistent with the SCC decision in Ewert v. Canada, 2018.

In addition to recommendations made by this Office, over the last decade, at least a half-dozen other reports, inquiries, and commissions have similarly issued recommendations to CSC on this very issue.Footnote 4 Similarly, since 2018, three parliamentary committees have conducted studies focusing on the experiences of Indigenous peoples in the federal correctional system.Footnote 5 Seven recommendations specifically related to the issue of assessment and classification practices, including for CSC to:

- develop new risk tools that are more sensitive to Indigenous reality;

- review its security classification process, generally, but with specific attention to Indigenous women;

- ensure tools provide Indigenous offenders with greater access to culturally appropriate treatment and healing lodges;

- partner with Indigenous communities to redesign classification tools and processes;

- ensure staff have proper sociohistorical training and information to properly conduct assessments; and,

- work with independent experts to ensure classification and assessment tools include dynamic factors, contextual factors, and the unique experience of marginalized groups.

Classification and assessment of Indigenous peoples serving federal sentences has also been a significant point of concern raised in two recent Auditor General (AG) reports. In 2016, in Preparing Indigenous Offenders for Release, the AG made recommendations to CSC which, among others, were to explore additional tools and processes of security classification.Footnote 6 Positively, the Service agreed with all recommendations. Six years later, however, the AG released a subsequent report on Systemic Barriers in Correctional Service of Canada and found most of the issues raised in 2016 remained. The 2022 audit found that CSC had “failed to address and eliminate systemic barriers that persistently disadvantage certain groups of offenders.”Footnote 7 Among their findings were that Indigenous individuals were placed at higher security levels at twice the average rate, were more likely to receive an override of their Custody Rating Scale (CRS)Footnote 8 to a higher security level, were given fewer overrides to minimum security, and that CSC did not monitor whether staff properly considered Indigenous Social History factors (ISH) for security classification decisions. All significant issues and barriers related to assessment and classification practices. Further to this second audit, the AG again recommended that CSC improve their security classification process by undertaking a review, with external experts, and taking any required action to improve the reliability of classification decisions. As was the case in 2016, the Service agreed with all of the AG’s recommendations.

CSC Responses and Actions to Date

Most recommendations issued by my Office and others remain largely unaddressed or little has materialized from the Service’s stated intentions. For over a decade, CSC has repeatedly indicated that they “recognize a need to ensure tools are culturally sensitive,” that it continues to work to ensure its tools are “effective and culturally sensitive” and are considering changes to determine the “cultural appropriateness” of case management and assessment of Indigenous peoples. For example, in response to the AG’s 2016 audit, CSC indicated that it would, “examine the need for and feasibility of developing new culturally appropriate assessment measures founded on the Gladue principles.” Two years later, in response to the SECU 2018 report, the Service noted that, “ongoing work is examining the need and feasibility of developing new culturally appropriate assessment measures founded on the Gladue principles, with the goal of ensuring that Indigenous offenders have access to effective, culturally appropriate programs and interventions as early as possible.” And as recently as 2021, in response to a recommendation made by this Office, CSC indicated that it was: “working with university partners on an Indigenous-led security classification process for Indigenous peoples in federal custody… to conceptualize, from the ground up, a risk assessment process for security classification, for both women and men inmates, that is culturally based.” Again, while these responses signal good intention, the Service has been unreasonably slow in its progress towards developing any new tools, properly examining the accuracy of existing tools, and making the tools they use culturally relevant for Indigenous peoples.

This Office has sought updates from CSC on this issue on at least five separate occasions since the Ewert decision. Through a documentation request in 2022, this Office was made aware of an ongoing Memorandum of Understanding and Service Exchange Agreement between CSC and the University of Regina, set to expire in the 2024, for a number of projects. Among these include a systematic review of the validity of risk assessments with Indigenous peoples and an Indigenous Community Engagement Strategy, intended to engage Indigenous communities to develop a research design for a project entitled: Validation of Risk Assessment Tools for Use with Indigenous Offenders. While the systematic review (conducted by external experts) has since been completed and published, there has been little observable progress on the development of any new research or culturally informed tools.

This Office met with, and was consulted by, the group of Indigenous-led researchers affiliated with the University of Regina. We are aware they provided the Service with a report and proposal, detailing what would be required to develop an Indigenous risk assessment tool; however, there do not appear to be any concrete plans in place for next steps on this work. In response to our recent and repeated attempts to obtain an update on all relevant work since the Ewert decision, it was shared by the Service that: “there have been challenges in the course of the undertaking of the research associated with the MOU, including changes in the University of Regina research team and in moving forward with Indigenous engagement strategies at the community level.” The Service continues to signal that the work “remains ongoing,” with more engagement and exploratory activities in the coming year; however, no further specific timelines or significant deliverables were identified, beyond consultation and strategy-building activities.

This Office recognizes that development of new tools from the ground up is a resource-intensive endeavour, and more so when led by external experts and with significant engagement by the community, as has been recommended; however, the development of new tools or practices is not new territory for the Service and should not be the cause for further delays. There is precedent for CSC developing tools, based in fieldwork and the consideration of group-level differences in their development.Footnote 9 At the writing of this report, CSC has still provided no public response to the Ewert decision. There are still no validated assessment or classification tools developed for or by Indigenous peoples and no anticipated timelines for one to be developed. There has also been no external primary research done by independent experts, of the CRS or other CSC-developed tools, or any concrete progress towards demonstrating proper consideration of ISH in decision-making, as evidenced by the AG’s most recent audit. This situation is unacceptable and inconsistent with the urgency and severity of what is at stake.

Systematic Review of Risk Tools

Of the steps taken by CSC thus far, it is worth noting some key findings from the systematic review it commissioned by independent academic experts.Footnote 10 In their review of 91 studies of 22 risk assessment tools, Olver et al. found that while most assessment tools, including many in use by the Service, meet at least the minimum threshold for statistical validity, for the majority of the tools, validity was found to be consistently poorer when these tools are used with Indigenous peoples. In other words, their ability to accurately assess the risk for outcomes is consistently weaker for Indigenous peoples. On this point, the research is clear and consistent – these tools consistently don’t work as well for Indigenous peoples. For some of the tools, including two developed and used by CSC, the accuracy for Indigenous peoples was among the worst of all 22 tools included in the review, just barely meeting statistically “acceptable” levels of validity.Footnote 11 They also found that there are currently no tools that incorporate culturally relevant factors in their estimations and measurements of risk. As these findings demonstrate, and as was argued in Ewert, there is a clear need (and responsibility) on the part of the Service, and other correctional agencies, to conduct research to better understand why these tools have consistently lower accuracy when used with Indigenous peoples and what needs to be done to address this gap. It should be noted that a number of tools CSC currently uses, including the Custody Rating Scale, were not included in this systematic review and therefore, more independent research is required.

Importantly, in addition to the meta-analytic findings, the experts offer some directions for correctional agencies, which warrant repeating here. Among them, they warn that correctional agencies should not place undue weight on assessments comprised of largely historical or unchangeable factors (i.e., “static” factors), as they have the weakest validity with Indigenous peoples and “the greatest potential for ethnoracial bias”. As many others have pointed out and criticized, most of the tools CSC currently uses to make decisions rely heavily on static factors, making it not only impossible to assess changes in risk or demonstrate positive progress, but also make Indigenous individuals appear higher risk due to the colonial causes at the root of most of these factors (e.g., age at first federal admission, sentence length, number of prior convictions). Some of the tools the Service uses to make decisions are comprised almost exclusively of static factors (e.g., Custody Rating Scale, Static Factors Assessment, Criminal Risk Index). Assessing static factors through these assessments undoubtedly contributes to the over-representation of Indigenous peoples in maximum security, difficulties and delays in cascading to lower security levels, gaining access to Healing Lodges, barriers to accessing programming, and delays in being granted timely release, among other problematic barriers and outcomes.

The researchers recommend that static tools be meaningfully supplemented with valid, dynamic measures (i.e., factors that can change over time and through intervention). As they put it, “to not do this is committing an act of social injustice.” They also call upon correctional agencies to conduct research on culturally specific risk factors, a recommendation that has been put to the Service many times. It remains to be seen how CSC intends to use the results of the work that it has commissioned and how evidence-based advice will inform any next steps.

Moving Forward

Last year, this Office released a report on Ten Years since Spirit Matters, an update on the state of various initiatives for federally sentenced Indigenous persons. It also marked 30 years since the implementation of the CCRA. As documented in this report, the troubling trajectory of the barriers and negative outcomes experienced by Indigenous peoples in the correctional system is counter to what was intended and expected when the CCRA was enacted. It is clear by most measurable outcomes that applying a one-size-fits-all approach to most practices and tools in corrections – including assessment and classification – is contributing to different correctional outcomes for Indigenous peoples. As Olver et al. so aptly reminded all correctional agencies, it is their responsibility in the application of any tool, that it be constructed and used in a “culturally responsive and anti-racist manner to promote decision-making that can maximize benefit and minimize harm.” The various sections of the CCRA pertaining to the treatment of Indigenous peoples, among other groups, were written as explicit direction to the government to address the systemic discrimination and harm Indigenous peoples have experienced through the course of history and to this day. As described in the Ewert decision, “The requirement that the CSC respect differences and be responsive to the special needs of various groups reflects the long-standing principle of Canadian law that substantive equality requires more than simply equal treatment.” CSC has fallen devastatingly short of this responsibility, which can in-part be attributed to a lack of substantive equality afforded to Indigenous peoples across most social institutions, including the prison system. Favouring an “equal treatment” approach in assessment and classification of Indigenous peoples, for example, is an illustration of this failure, the consequences of which are far reaching for those serving federal sentences.

With few exceptions, the common practice of developing generic tools based on the majority and applying them equally to groups with meaningfully different sociohistorical paths to the criminal justice system is a contradiction of this principle. And in the face of evidence demonstrating that these tools are inferior for Indigenous peoples, because they ignore such historical and social inequities, clearly suggests that better, different, tools and methods are needed. Tacitly accepting these disparities, while failing to advance meaningful improvements is tantamount to “an act of social injustice” and, per the Ewert decision, demonstrates contempt for, and constitutes a violation of, the rule of law.

In his May 27, 2022, Mandate Letter to the Commissioner of Corrections, the then Minister of Public Safety commended CSC on their work “to develop and incorporate Indigenous-informed risk assessment instruments and its efforts to fight systemic racism.” Based on the lack of observable progress, this praise seems grossly premature. It should not be forgotten that CSC was found to be in violation of the law by the highest court in the country. It is unacceptable to have made so little progress on this issue. CSC continues to use these tools and continues to insist that they are sufficiently valid for use with Indigenous peoples, in spite of Ewert and external research that it has commissioned. Six years later, the spirit of many of the arguments put forward in Ewert remains a cause for concern.

-

I recommend that the Service report publicly, in the next fiscal year, on concrete actions, deliverables, and timelines on how and when it will:

- acquire external, independent expertise to conduct empirical, primary research to assess the validity and reliability of all existing assessment and classification tools and methods used by CSC to inform decision-making with Indigenous offenders; and,

- develop new assessment and classification tools, Indigenous-led and from the ground up, for federally sentenced Indigenous peoples, that include culturally responsive and informed indicators of risk and need (i.e., Indigenous social history factors).

The Offender Complaint and Grievance Process

The right of a prisoner to make a complaint about mistreatment or conditions of confinement without fear of reprisal is a foundational principle of international and domestic human rights law. An effective complaint and grievance process encourages prisoner involvement as a means of resolving problems and conflicts at the lowest level possible and in a pro-social manner. There is evidence to suggest that when complaints are taken seriously and complainants are treated fairly and respectfully, incarcerated persons are more likely to accept and abide by decisions and rules, even if the outcome is not in their favour.Footnote 12 An effective prisoner redress process has the following core features:

- Prisoners have confidential access to a complaints process, and they have the capacity and means to use it.

- Prisoners have trust in the system, and they use it in good faith.

- Complaints are answered in a fair, timely and expeditious manner.

- Responses are meaningful, complete, and easily understood.

- Grievers do not suffer negative consequences for complaining.

On paper, the Correctional Service of Canada’s offender complaint and grievance policy and process reflects and incorporates these basic principles. Section 90 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) provides for a “procedure for fairly and expeditiously resolving offenders’ grievances.” Section 91 of the Act assures that every offender shall have “complete access” to a grievance procedure “without negative consequences.” One of the foundational legal principles of the CCRA provides for the existence of an “effective grievance procedure.” The Regulations further instruct that every effort will be made to resolve matters “informally through discussion.” Other provisions require giving reasons when rendering a decision on complaints, provide a mechanism for referring matters to an Inmate Grievance Committee, define a process for dealing with Multiple Grievers and outline criteria for rejection of complaints that are considered “frivolous, vexatious or not made in good faith.”

Commissioner’s Directive (CD) 081 – Offender Complaints and Grievances – and associated Guidelines 081-1 provide policy and procedures on how these legal rules are to be interpreted and applied by staff, including criteria on how to administratively prepare a response to a grievance and provide decisions that are clear, complete, impartial, and fair. There is further guidance on how to process certain grievances, for example, allegations of harassment or discrimination, or other submissions, such as transfers to Structured Intervention Units, the Special Handling Unit, or dry cells. Policy requires that these matters be automatically elevated to the final (or national) grievance level.Footnote 13 As of November 2019, initial health-related grievances are submitted directly to Health Services at the Regional level. The Assistant Commissioner, Health Services, is the decision-maker for health-related grievances making their way to the final level.

Since the phasing out of the regional level of complaint review in 2014-15, today the formal complaint and grievance system consists of three levels:

- Complaint – submitted at the institutional level, and responded to by the supervisor of the staff member whose actions or decisions are being grieved.

- Initial – submitted to the Warden (institutional level).

- Final – submitted to the Commissioner (national level).

When a griever is not satisfied with the decision at the complaint or initial level, they may escalate the matter to the next level, normally within 30 working days of receiving the response. According to policy requirements, routine priority issues submitted at the complaint and initial grievance levels are to be processed within 25 working days of receipt and within 15 working days for high priority matters. At the final level, processing requirements are extended to 60 working days for high priority grievances and 80 working days for routine priority grievances.Footnote 14 These requirements, including extended timelines to process final level grievances, have been in place since 2007.

Law and policy on these matters are clear and straightforward. Compliance, on the other hand is a matter of abiding concern, particularly as it relates to the capacity of the Service to address grievances within prescribed processing timeframes. The Office has frequently commented on the high number of unresolved complaints and grievances going forward to the next level and the excessive delays in processing them.Footnote 15 Up until very recently, it was not uncommon to wait up to a year to receive a response to a final level grievance (high priority or routine), and, in the case of an upheld grievance, even longer for a corrective action to be issued and implemented. The Office has often stated that internal dysfunction, delays and wait times of this magnitude are like having no remedy at all.

Purpose

This review updates Office findings in this important area and includes our latest assessment of the system’s ability to provide timely and effective redress. It acknowledges recent CSC efforts to address unprecedented and crippling backlogs in final level grievance review and reduce overall wait times. Our review calls on CSC to prioritize efforts to address complaints informally, and at the lowest level possible, before they can be escalated to become part of the formal grievance system. We encourage the Service to recognize the central importance of reallocating resources to better support the resolution of complaints and grievances at the institutional level. To that end, the Office calls on the Service to invest in training, skills, and capacity to successfully implement and sustain mediation and other alternative dispute resolution practices at all maximum-security and multi-level penitentiaries across Canada, including the Regional Treatment Centres and Women’s institutions.

Analysis of Complaint and Grievance Trends

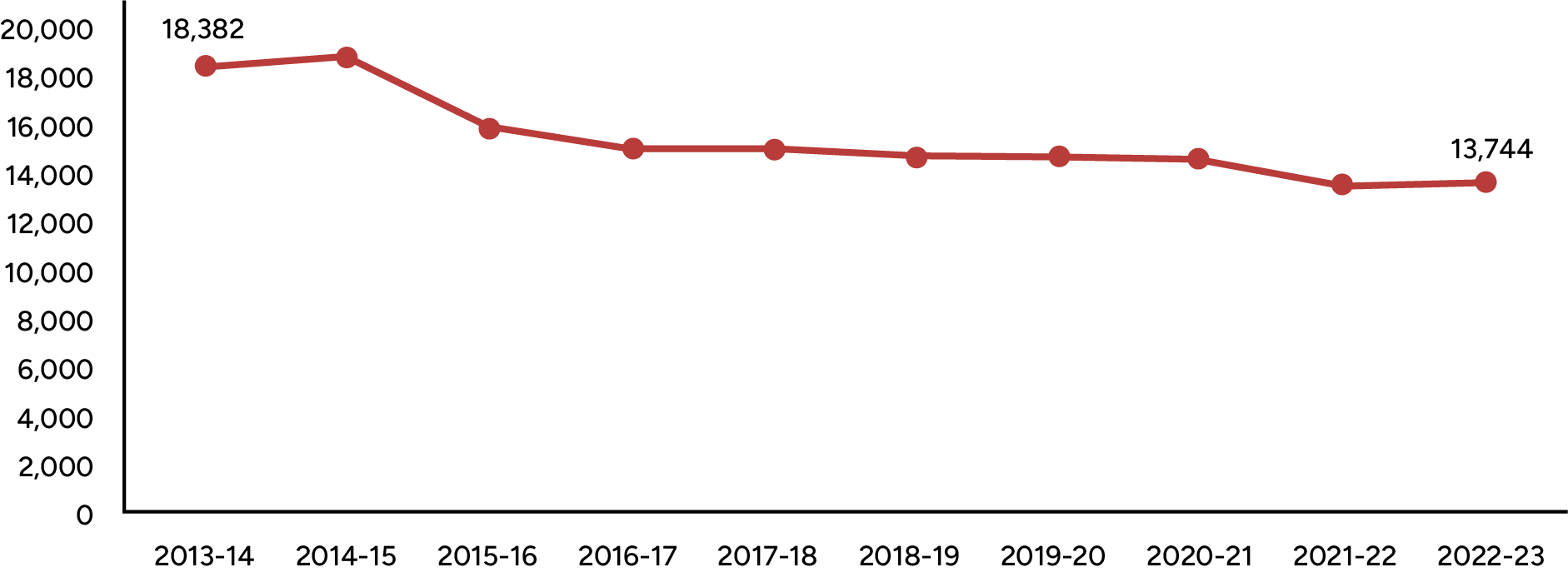

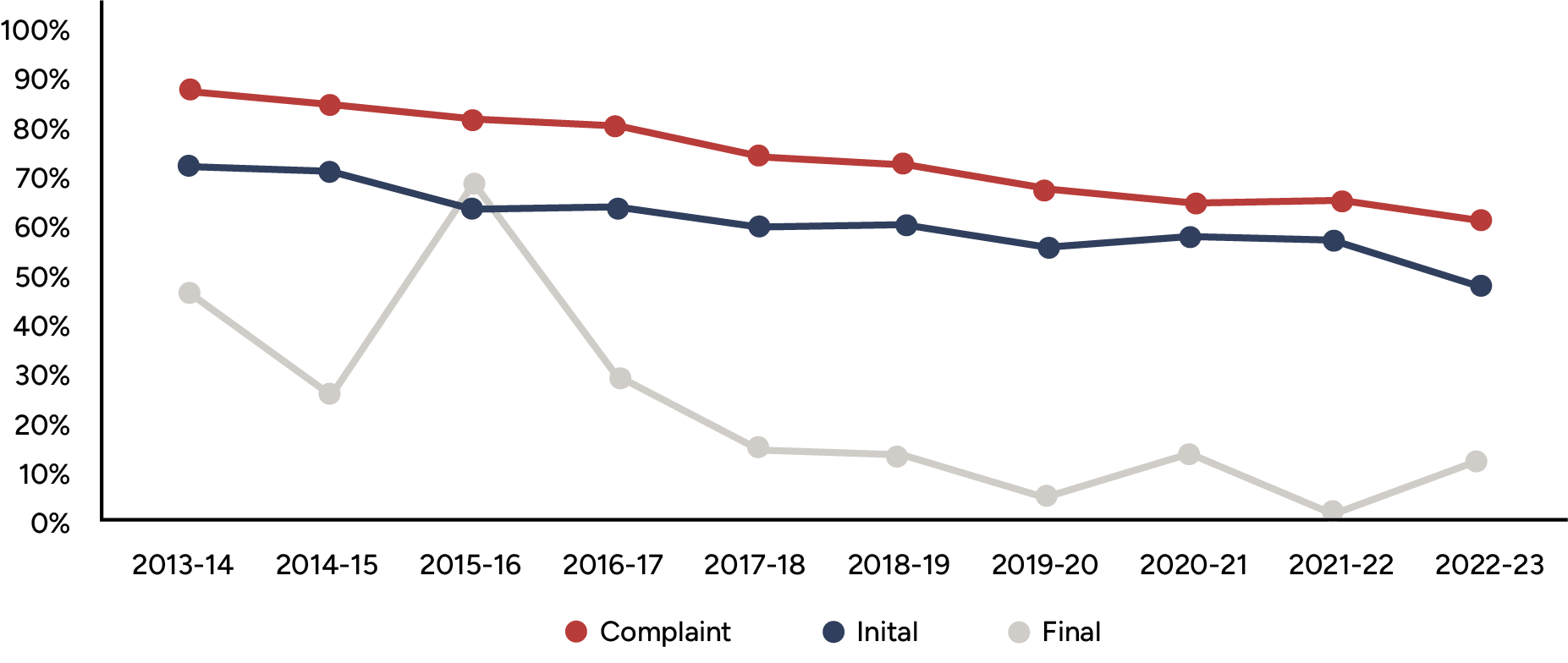

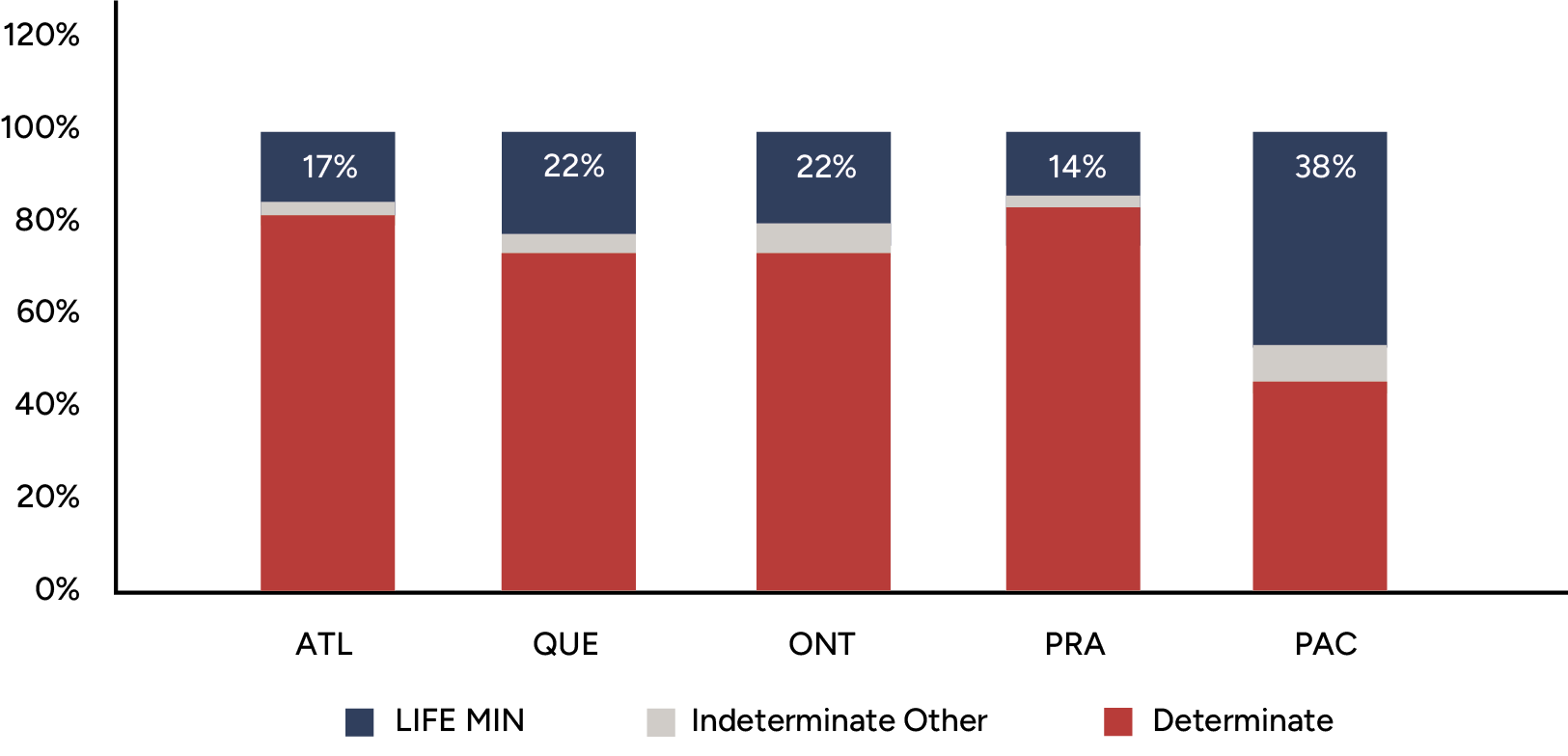

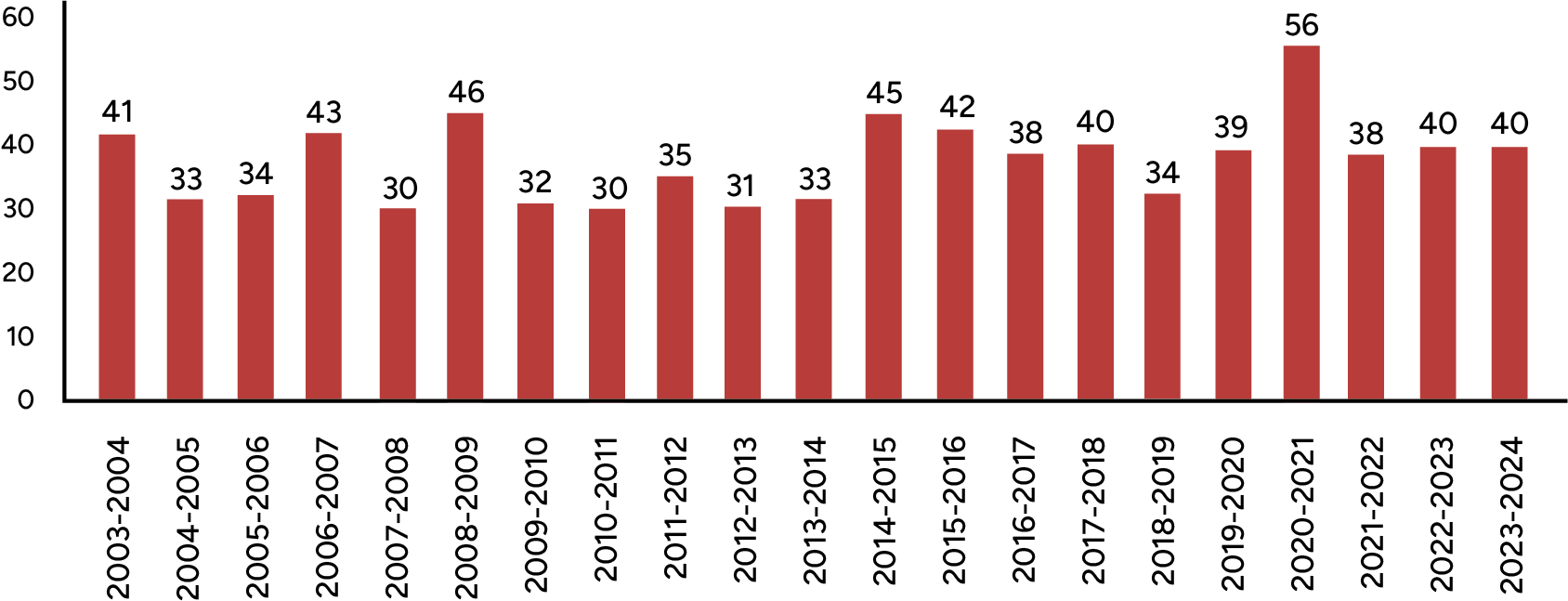

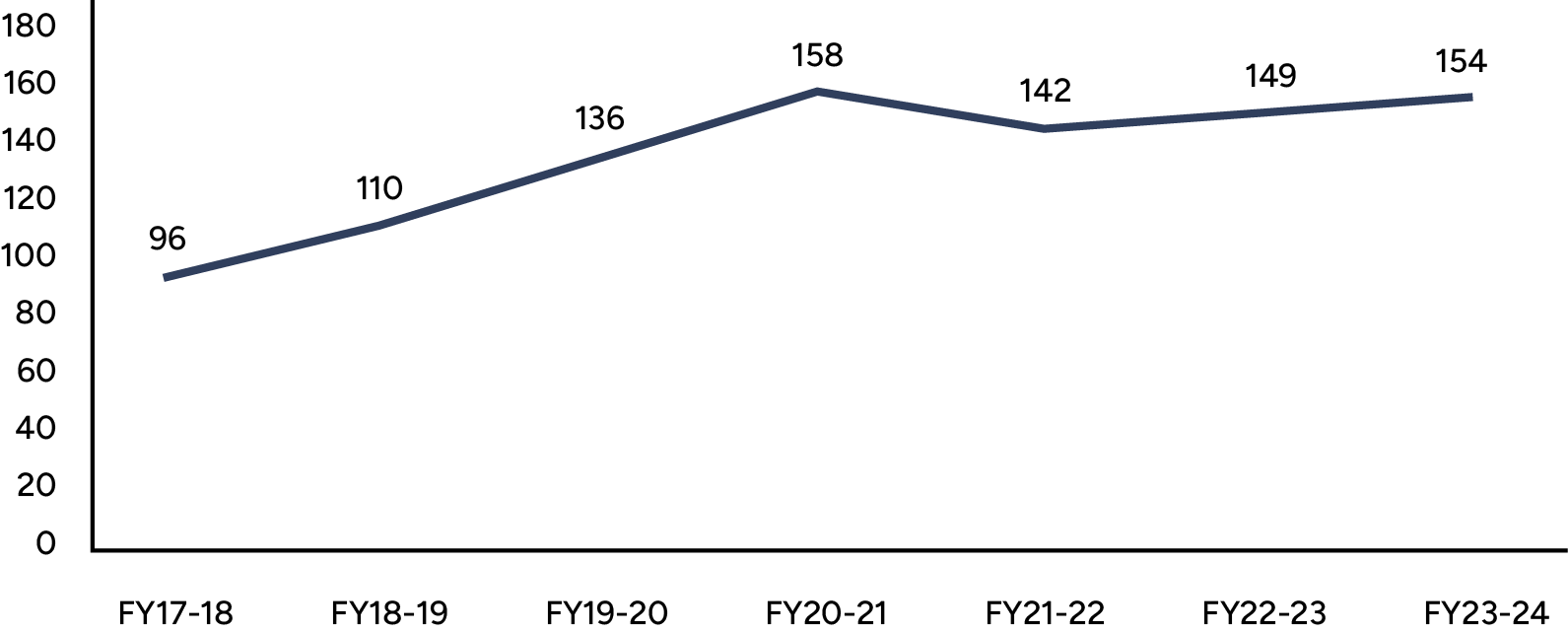

Ten-year trend data indicates that the overall number of complaints and grievances has decreased, and this trend seems to have picked up pace in the post-Covid period (see Graph 1). At the same time as the volume of complaints is decreasing, the number of grievances answered within prescribed timeframes has generally declined since at least 2016-17.

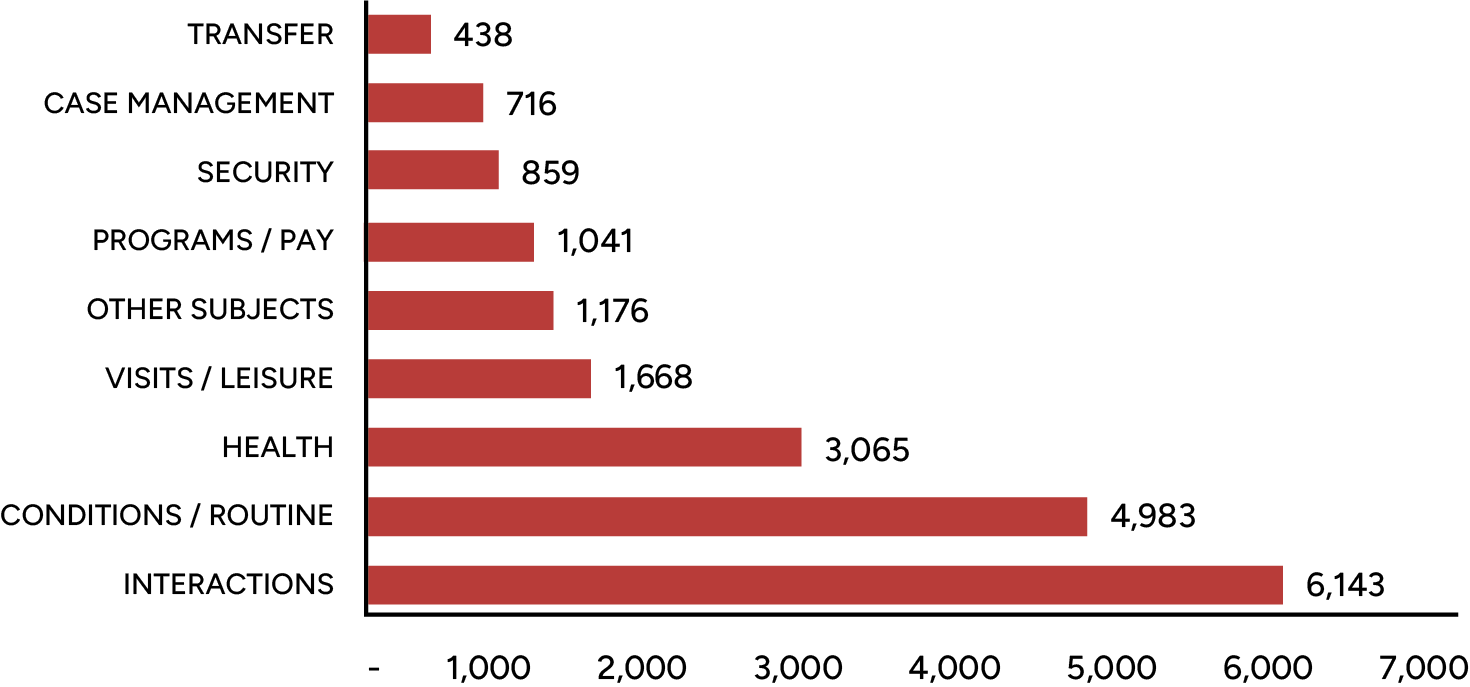

Over the same period, the complaints related to institutional conditions/routine (32.6%; e.g., food, diet, amenities), interaction (19.6%; e.g., staff performance), and health care (15.4%) accounted for more than two thirds of all complaints (see Table 1 in the Appendix for a complete breakdown). These subjects broadly mirror the top categories of complaints received annually by the OCI.

Disaggregating complaints by the ethnicity of the complainants, the numbers and proportions generally reflect changes in the overall demographic distribution and diversity of the federally incarcerated population (see Table 2 in the Appendix). For example, the proportion of complaints submitted by White prisoners declined from 62% in 2013-de14 to 53% in 2022-23 and has increased for Black prisoners from 9% to 11% within the same period. For Indigenous prisoners, the proportion of complaints reflects their growing representation, i.e., from 24% of all complaints in 2013-14 to 31% in 2022-23.

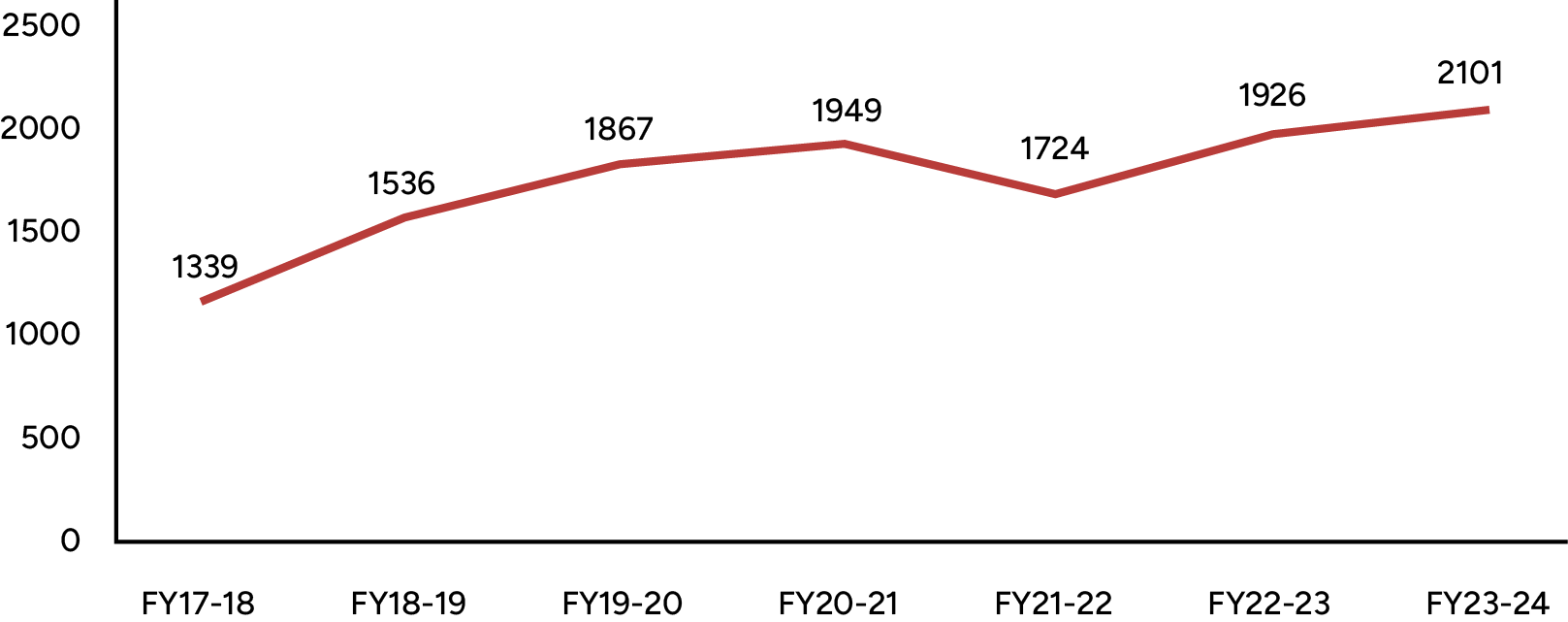

GRAPH 1. TOTAL NUMBER OF COMPLAINTS SUBMITTED BY FISCAL YEAR

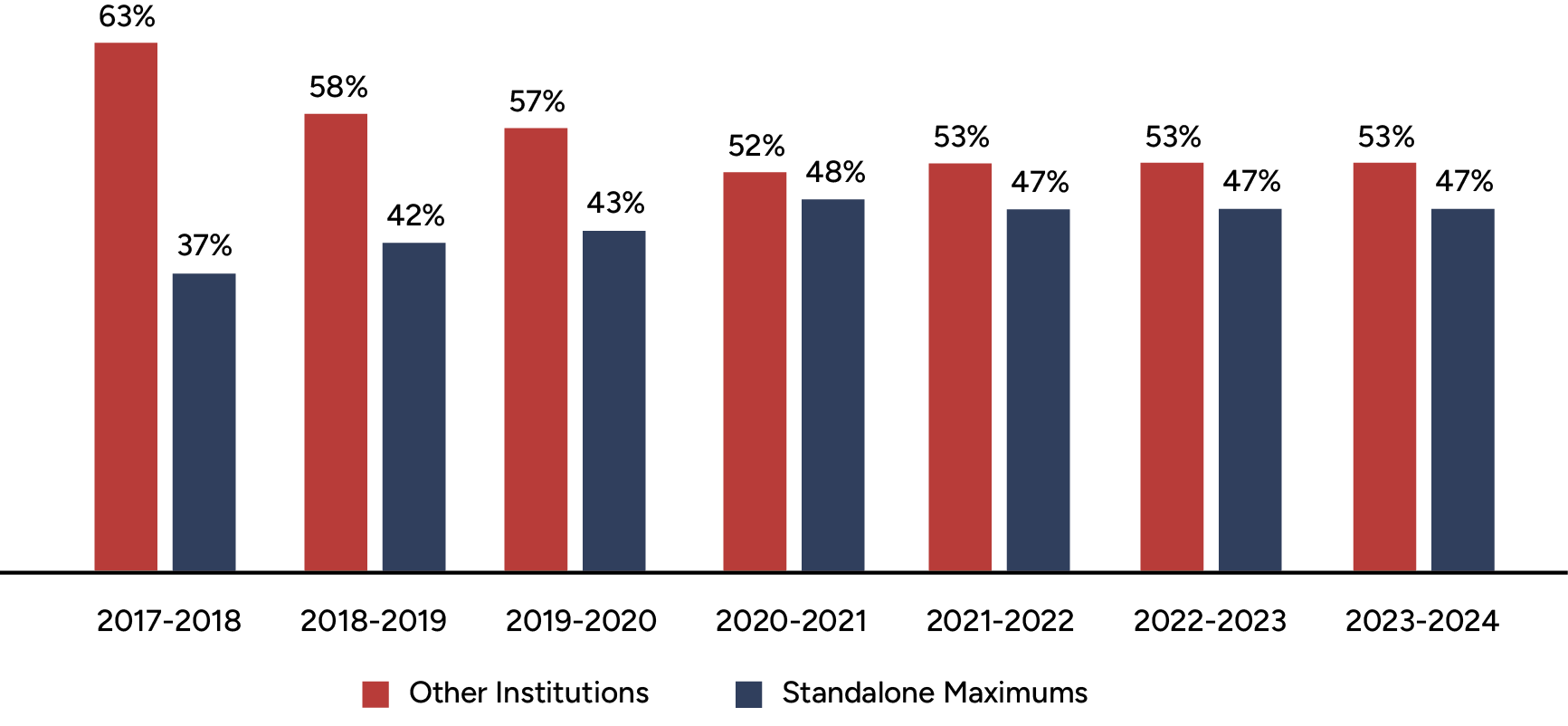

GRAPH 2. PROPORTION OF GRIEVANCES PROCESSED ON TIME BY LEVEL AND FISCAL YEAR

Trend data also shows that the proportion of grievances being processed on time has generally decreased (Graph 2). More recently, the number of grievances processed on time at the national level is showing substantive improvement.

Approximately 75% of all grievances reaching the final (or national) level are designated routine priority, meaning they should be resolved within 80 days. Since 2013-14, less than 30% of all routine grievances were completed within prescribed timelines (see Table 3 in the Appendix). The proportion of high priority grievances completed on time (within 60 days) was even less, averaging around 25% (see Table 4 in the Appendix). As the statistical tables indicate, 27.8% of all high priority grievances took more than 301 days to complete while 21.3% of routine grievances averaged more than 301 days to complete.

During this investigation, CSC advised that current processing times for final level grievances are now much closer to policy guidelines, gradually decreasing from 360 days in 2020, 310 days in 2021, 130 days in 2022 and now to less than 60 days. For the first time in CSC’s history, the Office was also informed that there will be no backlog of final level grievances by fall 2024.

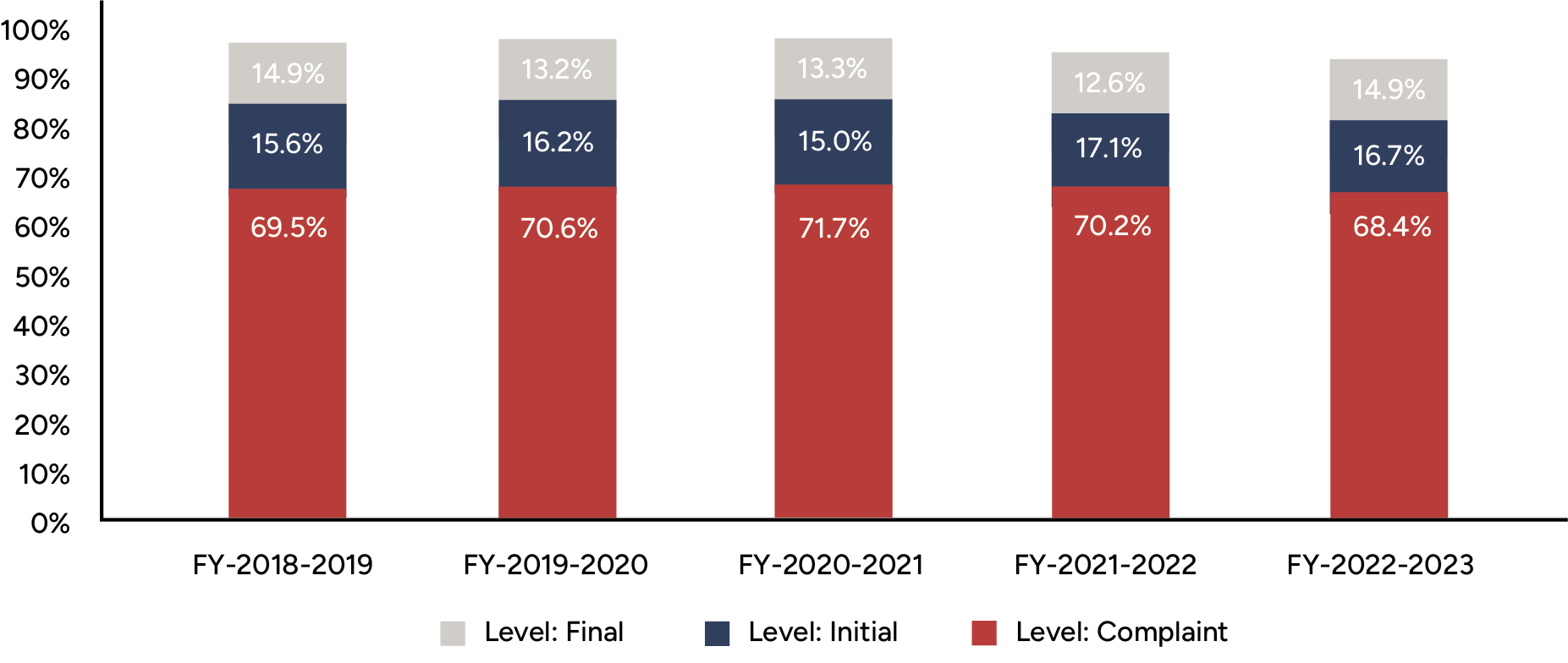

While recent trends in processing final level grievances are encouraging, the Service’s ability to comply with prescribed processing timeframes is symptomatic of other problems. In the same way that “justice delayed is justice denied,” the proportion of complaints that fail to be resolved informally through discussion, and those that are routinely escalated to initial, and then final decision levels raise serious concerns about the system’s commitment to timely and effective redress. Few within or outside the Service would argue with the premise that routine issues at the institutional level should be properly and promptly dealt with at their source. However, once matters surpass the complaint stage, there is, in fact, not much variation between the proportion of grievances submitted at the initial (or institutional) level and those that are escalated to the final level. In other words, while many complaints get resolved at the first complaint stage, a high proportion of initial grievances at the institutional level are unresolved and get pushed to the national level of grievance review.

GRAPH 3. PERCENTAGE OF GRIEVANCES BY LEVEL (2018-19 TO 2022-23)

There is no easy or single explanation for this degree of redundancy. In fact, there are few disincentives to escalating or bumping issues upward and onward; some grievers and even some staff wrongly assume that the national grievance level acts as a kind of final “appeal” stage. Some users seem to be of the belief that their complaint will only be taken seriously if it is elevated to the next level in the process. The commonly heard expression – “let national decide” – provides a convenient excuse for putting off dealing with sticky or potentially divisive issues at the institutional level. Though it may, at times, help a Warden to save face with staff, it does not save time. To put the same matter differently, there are few built-in incentives for institutional authorities to settle a complaint or answer a grievance on time.

Whatever the cause, the current operation of the complaint and grievance process does not seem designed in a way to support or deliver outcomes that are timely or responsive. In cases requiring more time for response preparation, it is standard practice to issue an extension letter, which is supposed to include a reason(s) for the delay and a revised date that the griever should expect to receive a response. A 2018 internal audit of the Offender Redress system found that these extension letters often took the form of a standard template, and often failed to provide a specific reason for why the response was delayed, or even when a response could be expected.Footnote 16 CSC claims that maladministration of this nature is now less common at the final grievance level; however, the issue of “overdue” responses at the initial (institutional) level remains, regardless of whether an extension letter (with revised due dates) was provided or not, leading to frustration and lack of confidence in the system.

Though the quality of responses varies from one level to the next (generally improving as the complaint makes its way up), there is a tendency to answer grievances impersonally, in the third person, and usually in a manner that adheres to the strictest definition and letter of the governing regime. In the Office’s experience in reviewing CSC responses to complaints, it often seems that the respondent is well versed in parsing, limiting, or rejecting the substance of complaints on procedural or technical grounds (e.g., out of jurisdiction, deadlines for escalation not respected, grievance raises a new issue, or an issue that has been addressed in a separate submission). Resolution or rejection often settles on the point of least resistance. There may be limited scope for acting on a grievance, but there is ample room to appeal to a higher level when grievers do not get the redress they wanted or expected.

Though the data and analysis amassed by the complaints and grievance system should provide management with important insight into emerging trends or issues of concern, it is not clear that these tools are being used optimally to monitor or improve performance. The latest audit of Offender Redress explains:

[Commissioner’s Directive 081] … does not clearly assign responsibility or accountability for the Service-wide process to any single group. The result is a fragmented process, whereby Offender Redress Division is responsible for response activities at the national level and each site is responsible for managing their own respective process, resulting in potentially dozens of varying complaint and grievance processes across the Service, and no cohesive plan in place to resolve complaints and grievances at the lowest possible level. This increases the likelihood of diminished response capabilities, impacting offender confidence in the institutional process and resulting in reoccurring backlogs at the national level.Footnote 17

In other words, there is no governance mechanism in place to prevent future backlogs at the final level, little national capacity to support institutions to better manage complaints informally and at the lowest possible level, and no plan to better prevent escalation of complaints and grievances from one level to the next. Five years later, senior management has had more than enough time to address these identified deficiencies. Notwithstanding, there are few indications today that there is willingness to strengthen national oversight or overall accountability of the complaint and grievance system, bolster efforts to resolve matters informally, or improve the use and analysis of complaint and grievance-related data to drive performance. In the absence of national oversight and leadership, the redress systems which independently operate at each site cannot be expected to respond in a consistent or coordinated manner.

Lack of Focus and Priority on Informal Resolution

Ideally, before a prisoner even files a written complaint, the Act instructs that every attempt be made to resolve issues informally. For many reasons, the statutory requirement to resolve matters at the lowest level possible through discussion is not a well established or ingrained practice, particularly at higher security level institutions. In fact, according to the 2018 audit, “evidence was often lacking to demonstrate that staff members at the institutional level had made an active effort in attempting to resolve matters informally.”Footnote 18 Beyond a one-page Annex appended to the back of the Guidelines, there is little actual or active policy direction on how to facilitate or implement informal or alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms in federal prisons. Though the same Annex indicates that ADR must remain available throughout all stages of the redress process and that National Headquarters “is prepared to assist institutions in identifying and implementing alternative dispute resolution mechanisms,” during this investigation the Office encountered only one active ADR project, which is running as a pilot at Kent Institution. Lacking ongoing and a permanent source of funding, this promising pilot is soon set to expire.

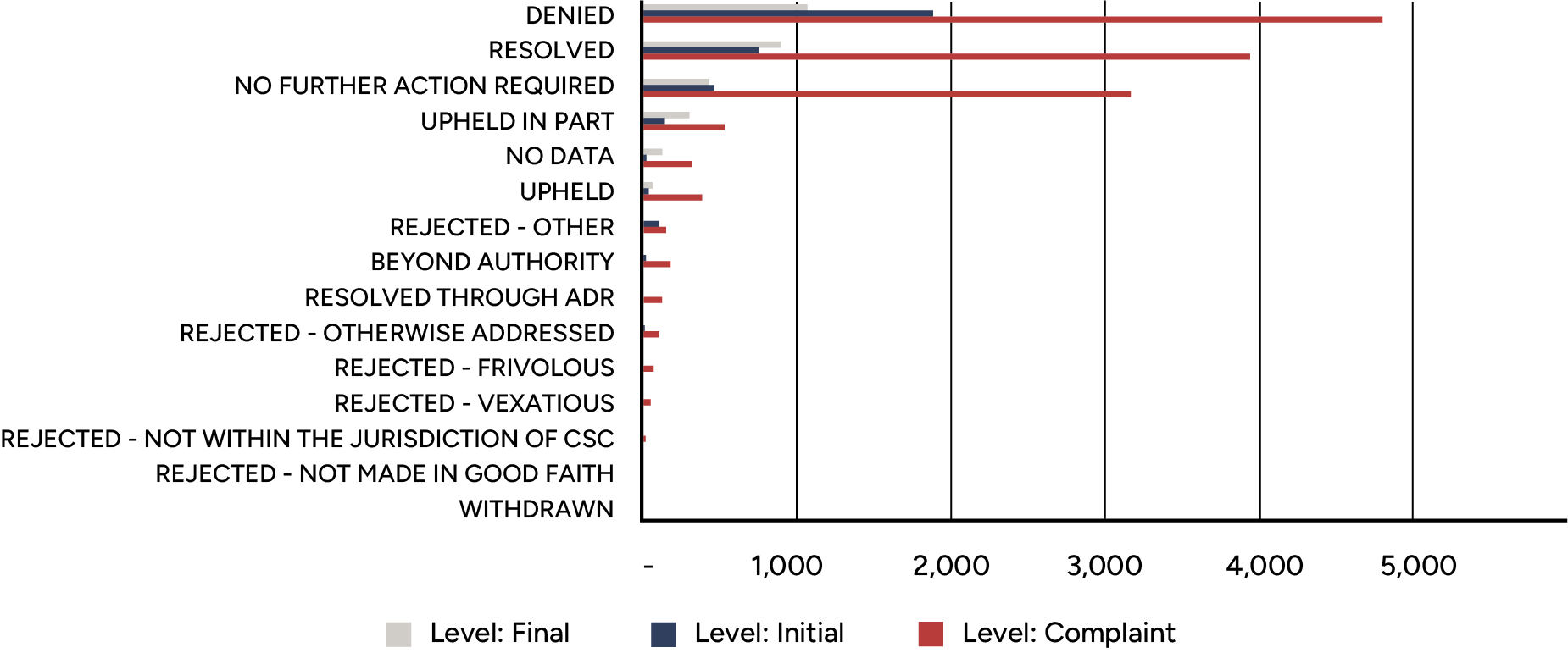

Moreover, the data indicates that only a small number of complaints are resolved through ADR (see Table 5 in the Appendix). With respect to the disposition of complaints, they are answered, in ascending order, as Denied, Resolved, No Further Action Required, Upheld or Rejected. Only a small fraction of the thousands of complaints and grievances filed each year are found to be “upheld.” Further, the proportion of Upheld grievances has declined over the past decade, from 1,030 or 3.6% of all grievances in 2012-13 to 532 or 2.7% in 2022-23 (Graph 4).

GRAPH 4. TOTAL NUMBER OF GRIEVANCES IN 2022-23, BY DECISION AND LEVEL

As the Office found this year in investigating the standalone male maximum-security institutions, many of the components that support or feed into the formal complaints and redress process are either delinquent, defunct or deficient. This includes Inmate Welfare Committees (IWCs), Outside Review Boards, Inmate Grievance Committees, and Inmate Grievance Clerks. On the matter of incarcerated person involvement, an effective redress process relies on a functioning and recognized IWC where discussion and negotiation between elected Committee members and management can help to raise and resolve group matters before they become the subject of multiple individual grievances. At maximum-security sites, the tendency to appoint or acknowledge range representatives as a substitute for the IWC reinforces intra-group divisions and fuels the incessant conflict between sub-population groups in these institutions.

Lacking internal coherence, the system seems to respond to periodic pressures by extending prescribed processing time limits, delaying redress, and amassing backlogs. From users, these systemwide failures serve to increase distrust and lack of confidence in the system among federally sentenced individuals. In recent years, an enormous amount of effort and resources has been expended to clear a backlog in final level grievances that, by December 2020, had peaked at close to 4,000 submissions. This extraordinary effort included the formation, in November 2022, of a National Complaint and Grievance Resolution Review Committee. As part of its mandate, this Committee set out to review and address complaints filed by a select number of prolific grievers, a few of whom are responsible for hundreds of complaint submissions. There were a few important takeaways from the Committee’s work, not least of which include never underestimating the importance that incarcerated persons place on the opportunity to air their grievances in person, to be taken seriously and to be heard by decision-makers. Though this level of engagement led to its own share of concerns and complaints, the learning points reflected below are instructive:

The in-person interviews gave the offenders the opportunity to express their concerns and allowed for the committee to engage them in the resolution of their complaints and grievances. The committee’s presence at the operational sites meant the committee members could see firsthand what the complaints were about and work with operational staff to come up with solutions. The participation of offenders and the support of the regional and operational sites were key to resolving the majority of complaints, and to the success of the project.Footnote 19

Other measures to reduce grievance backlogs have been more contentious. In March 2017, temporary funding supporting alternative dispute resolution projects at ten penitentiaries was suspended and significant resources reallocated to National Headquarters to address the backlog of final level grievances. At that time, even though the suspended ADR projects were showing early but consistent signs of success, considering the growing backlog in final level grievances, this priority reallocation exercise appeared defensible. In retrospect, it is now conceded that a reciprocal level of training, skills, resources, and priority is required to front-load the process to actively support and strengthen informal resolution of complaints at the lowest level possible, and thereby reduce pressures on other levels of the system. The learnings gleaned from these two “unclogging” exercises should quash any remaining doubt that mediation and fully supported and funded alternative dispute resolution programs should be made available in all federal penitentiaries.

The Issue of Reprisals

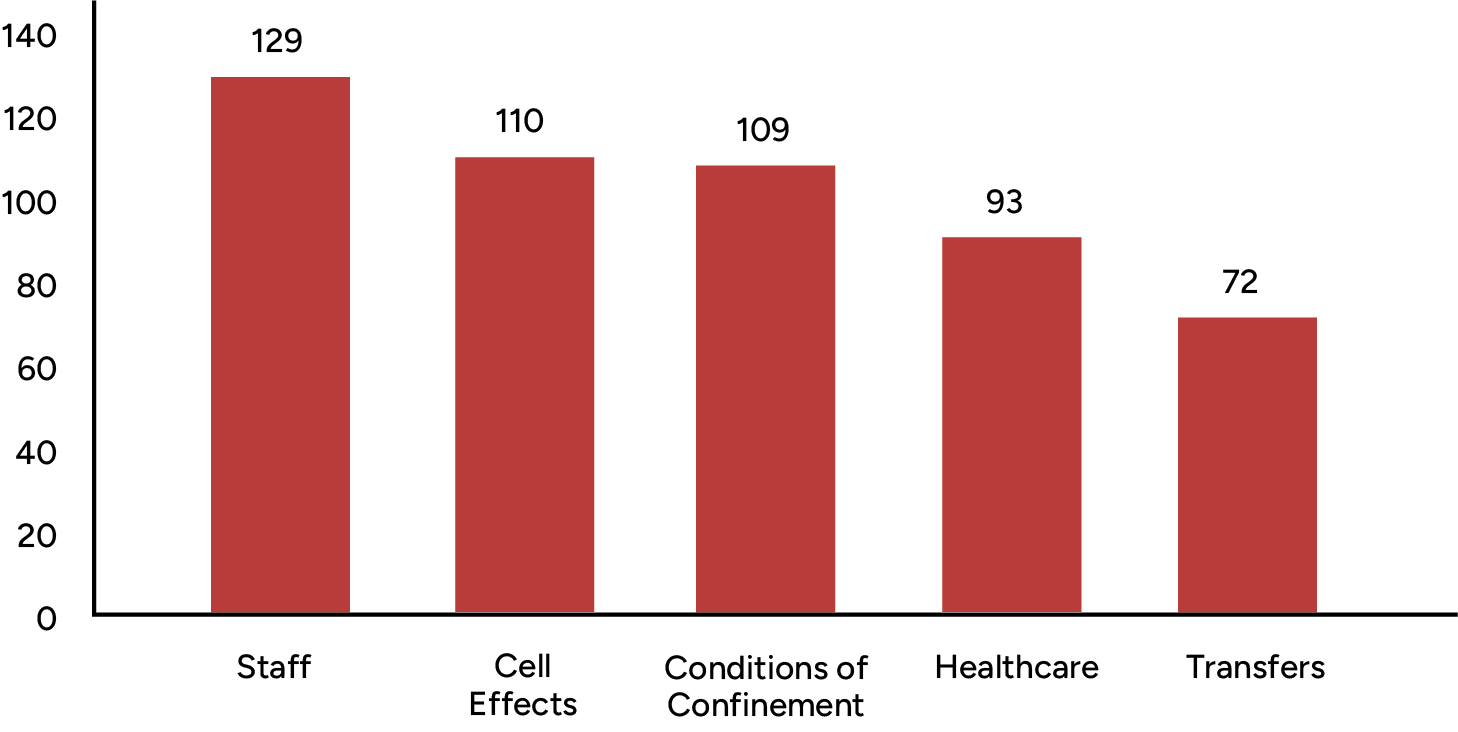

Incarcerated people continue to express widespread lack of trust and confidence in the system, often describing it as “flawed” or “useless”. As the Senate Committee on Human Rights recently reported, most had given up trying to use the system because of delays, backlogs, and the fear of potential reprisal from staff. The Committee heard that prisoners have little faith in the system because, in their eyes, it lacks credibility and independence.Footnote 20 For example, when complaints of mistreatment are made against a staff member, responsibility for responding to those allegations falls to that person’s immediate supervisor. Perceptually and procedurally, there is little separation between the staff member who may be the subject of the complaint and the work colleague who assesses it. Complaints and grievances against staff, often falling under the larger category of “Interaction” (see Graph 5), are very difficult to prove and establish; these complaints are rarely deemed to be founded and even less likely to be upheld. Given that “staff performance” accounts for the largest single complaint filing under this category of complaints, it seems a natural fit to resolve these issues through mediation or ADR.

GRAPH 5. TOTAL NUMBER OF GRIEVANCES RECEIVED BY SUBJECT IN 2022-23

Note: The subject “Interactions” includes Cross-Gender Staffing (4), Discrimination (1,230), Harassment by staff (710), Sexual Harassment (64), and Staff Performance (4,135). The subject “Conditions/Routine” includes Food and Diet (758), Institutional Amenities (786), Personal Amenities (230), Appeals on claims against the Crown (218), Conditions and Routine in the Institution (881), Offender Accounts (376), Offender Canteen (251), Personal Effects (1,362), Deductions for Food, Accommodation and Telephone Administration (17), Shared Accommodation (104).

On the point of reprisals, the Senate Committee’s report states:

The Committee also heard that federally sentenced persons can face intimidation and retaliation for filing grievances or even for inquiring with correctional staff about filing grievances. According to witnesses, reprisals could take various forms including harassment, destruction of property, loss of privileges, interference with correspondence, visits and programming, neglect of responsibilities, excessive use of force, and delays in completion of paperwork as well as lack of support for access to programs and conditional release.Footnote 21

While conducting this investigation, my Office heard many of the same allegations, though the reality of reprisal or retaliation for using the complaint and grievance process manifests itself in less subtle ways. Interference, pressure, and intimidation can and does happen. These actions often take the form of pressuring complainants into withdrawing their complaint, or agreeing to sign off that a grieved matter was “resolved,” even if it had not been addressed to the complainant’s satisfaction or proposed remedy. When it comes down to it, there are few protections afforded to grievers who fear or experience negative consequences for exercising their right to complain.

The redress system is consumed by paperwork and endless compliance reporting; from the outside, it appears more focused on meeting or extending established timeframes than providing substantive redress. Befitting a system that is primarily paper-based, responses to formal grievances are prepared and delivered in writing. The request or opportunity for grievers to speak with CSC staff regarding the status or substance of their complaint or grievance is not always accommodated. Responses are frequently delivered by the Grievance Clerk, and rarely by the person who is the subject or assessor of the complaint. Though it might be easier and administratively more convenient for staff to instruct an aggrieved person to “put it in writing,” such a requirement should not diminish or devalue the integrity of the complaint or the person making it, as so often seems to occur. Literacy and language barriers aside, a complaint process that relies exclusively on the submission, review, and signing of forms does not necessarily, in and of itself, encourage “good faith” engagement, by either party.

The general impression is that the system does not often yield satisfactory or quality outcomes, for either complainants or responders. Direct and personal accountability is often lacking. As one CSC respondent put it, what is missing from the complaint resolution process is genuine “person-to-person engagement.” It is significant to note that one of the successful practices emerging from the latest effort to address the national backlog of grievances was the condition to meet with and interview grievers in person. Providing a trusted and confidential intermediary (mediation) between staff and grievers and giving complainants an opportunity to be genuinely heard are recognized best practices that open the possibility of improving timely and effective redress. The current process could benefit from applying more attention to and compliance with the pillars of procedural justice – fairness, voice, respect, trust, transparency, impartiality, and neutrality.

THE FOUR PILLARS OF PROCEDURAL JUSTICEFootnote 22

Conclusion

The broader policy and practical implications of this review should be in clear view. It is obvious that the upward movement of complaints and grievances without resolution from one level to the next is inefficient, resulting in periodic backlogs and unnecessary and lengthy delays in processing and redress times. There is a clear need to make investments and place far greater emphasis on the legal obligation to provide for informal resolution of complaints at the lowest level possible. Given that the law mandates such a focus, this finding should not come as a new insight.

Fourteen years ago, in 2010, an external review of the complaints and grievance process came to the same conclusion that CSC was not applying enough effort or resources to informal resolution of complaints. That review recommended that all maximum and medium security penitentiaries should have “a suitably qualified person designated as an Offender Complaints and Issues Mediator, appointed at management level.”Footnote 23 Further, the review stressed that all staff having any interaction with incarcerated persons should be properly and adequately trained in the law and operation of the redress system, as well as the basic skills of informal dispute resolution. Now that the national grievance backlog has been mostly cleared and compliance with prescribed timelines is finally in view, it seems timely to implement mediation in all federal prisons.

It will not be easy to revive ADR practices or implement a viable mediated dispute resolution program into contemporary correctional practice. The training, skillset and personal attributes required for successful mediation in a prison context – empathy, neutrality, confidentiality, trust, ability to listen, problem-solving, patience, strong interpersonal and negotiation skills – are not easily transferrable. It is recognized that conflict resolution involving a mediator can be lengthy and demanding, and, in a prison context, doubly challenging for practitioners to be perceived as impartial or neutral parties. Both sides must have confidence and trust in the person and the process. Selection of suitably trained, qualified, and skilled candidates must be carefully considered.

As the Ombuds for federally sentenced persons, I acknowledge that my Office has a direct interest in the Service moving forward with ADR, and, in particular, mediation. It bears reminding that complaints filed against CSC are often the same issues that are brought to my Office for resolution. Not surprisingly, in some of the most important and highly contested complaint areas – conditions/routine, staff interaction, health care – there is considerable overlap. Moreover, prisoners are not required to exhaust CSC’s internal system before accessing Office resources. Inefficiencies arise when unresolved issues, requests, and complaints that are minor or routine in nature simultaneously make their way over to my Office. It is safe to say that the same legislation that governs CSC and its oversight body did not anticipate this degree of duplication and redundancy. It is not in the continuing interest of CSC, my Office, or even grievers for that matter to be engaged on the same complaint at the same time.

The escalation of complaints from one level to the next or from one entity to another tends to harden positions, frustrate decision-makers, and perpetuate distrust. In too many cases, the formal grievance process is not delivering timely or reasonable redress. As with the de-clogging exercise, there is need for strong national leadership, mentorship, and oversight of the redress system. Mediated resolution needs to be taken seriously. It demands to be regarded as a fundamental component of the formal and informal redress system. Past experience dictates that ADR should not be an afterthought, add-on, or another pilot project that ends when temporary funding runs out. Ownership and accountability for the national redress system properly belong with the Offender Redress Division at CSC National Headquarters.

Given the power imbalances that are inherent between complainants and respondents in the context of imprisonment, there continues to be a need to retain the requirements of a formal complaint and grievance system. ADR is not a substitute or suitable remedy for settling certain and serious human rights violations, and it may not be appropriate for addressing allegations of discrimination or harassment. That said, it must be recognized that the current paper-based process can work to discourage, disempower, or otherwise delay dealing with the substance of legitimate complaints and grievances. Lack of access to other means of resolving disputes leads to their inevitable escalation, resulting in frustration and delay that encumbers timely and effective redress.

-

With respect to CSC’s internal Complaints and Grievances process, I make three summary recommendations, to be phased and completed within the next fiscal year:

- First, CSC should conduct a principle-based review of the complaints and grievance process informed by the pillars of procedural justice – voice, respect, neutrality, trustworthiness. The views and experiences of incarcerated people should be taken into consideration throughout this review.

- Simultaneously, CSC should undertake a reallocation exercise to ensure proper and sustained focus, effort, and priority will be placed on resolving complaints and grievances informally, and at the lowest level possible. This could include reallocation of resources from national level redress to penitentiary-based resolution.

-

Finally, CSC should make significant investments in mediation and alternative dispute resolution training and skills building for all staff with the goal of implementing these practices at all maximum-security and multi-level penitentiaries across Canada, including the five Regional Women and Treatment Centre facilities. ADR and mediation would be central and permanent features of a significantly updated and revised Commissioner’s Directive 081.

Appendix

CSC’s Complaint and Grievance Process: By the Numbers

TABLE 1. TOTAL NUMBER OF COMPLAINTS SUBMITTED BY SUBJECT

| 2013- 2014 | 2014- 2015 | 2015- 2016 | 2016- 2017 | 2017- 2018 | 2018- 2019 | 2019- 2020 | 2020- 2021 | 2021- 2022 | 2022- 2023 | |

| TOTAL | 18,382 | 18,684 | 15,861 | 15,099 | 15,042 | 14,723 | 14,777 | 14,693 | 13,661 | 13,744 |

| Case Management | 1,021 | 917 | 824 | 670 | 720 | 686 | 621 | 590 | 600 | 507 |

| Conditions / Routine | 6,185 | 6,599 | 5,363 | 5,315 | 4,849 | 4,684 | 4,553 | 4,643 | 4,401 | 3,826 |

| Health | 2,113 | 2,347 | 2,112 | 2,148 | 2,229 | 2,550 | 2,290 | 2,814 | 2,585 | 2,632 |

| Interaction | 3,345 | 3,357 | 3,152 | 2,763 | 3,081 | 2,650 | 3,034 | 2,953 | 2,777 | 3,240 |

| Other Subjects | 636 | 613 | 423 | 434 | 471 | 403 | 369 | 652 | 541 | 668 |

| Programs / Pay | 1,795 | 1,765 | 1,377 | 1,172 | 1,107 | 1,063 | 991 | 983 | 825 | 887 |

| Security | 940 | 1,082 | 789 | 744 | 668 | 817 | 719 | 574 | 533 | 583 |

| Transfer | 23 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 18 | 9 | 14 | 3 | 5 | 9 |

| Visits / Leisure | 2,324 | 1,995 | 1,814 | 1,843 | 1,899 | 1,861 | 2,186 | 1,481 | 1,394 | 1,392 |

TABLE 2. TOTAL NUMBER AND PROPORTION OF COMPLAINTS BY ETHNICITY, BY FISCAL YEAR

| 2013- 2014 | 2014- 2015 | 2015- 2016 | 2016- 2017 | 2017- 2018 | 2018- 2019 | 2019- 2020 | 2020- 2021 | 2021- 2022 | 2022- 2023 | |

| TOTAL COMPLAINTS | 18,382 | 18,684 | 15,861 | 15,099 | 15,042 | 14,723 | 14,777 | 14,693 | 13,661 | 13,744 |

| Indigenous | 4,353 | 4,412 | 3,867 | 3,953 | 3,835 | 4,139 | 4,207 | 4,328 | 4,193 | 4,250 |

| Non-Indigenous | 14,054 | 14,276 | 11,995 | 11,148 | 11,209 | 10,584 | 10,570 | 10,367 | 9,467 | 9,490 |

| Black | 1,682 | 1,779 | 1,771 | 1,468 | 1,461 | 1,174 | 1,362 | 1,256 | 1,148 | 1,445 |

| White | 11,390 | 11,569 | 9,445 | 8,938 | 8,955 | 8,708 | 8,434 | 8,312 | 7,481 | 7,234 |

| 2013- 2014 | 2014- 2015 | 2015- 2016 | 2016- 2017 | 2017- 2018 | 2018- 2019 | 2019- 2020 | 2020- 2021 | 2021- 2022 | 2022- 2023 | |

| Indigenous | 23.7% | 23.6% | 24.4% | 26.2% | 25.5% | 28.1% | 28.5% | 29.5% | 30.7% | 30.9% |

| Non-Indigenous | 76.5% | 76.4% | 75.6% | 73.8% | 74.5% | 71.9% | 71.5% | 70.6% | 69.3% | 69.0% |

| Black | 9.2% | 9.5% | 11.2% | 9.7% | 9.7% | 8.0% | 9.2% | 8.5% | 8.4% | 10.5% |

| White | 62.0% | 61.9% | 59.5% | 59.2% | 59.5% | 59.1% | 57.1% | 56.6% | 54.8% | 52.6% |

TABLE 3. TOTAL NUMBER OF FINAL GRIEVANCES COMPLETED BY WORKING DAYS TO COMPLETION

| DAYS TO COMPLETION |

2013- 2014 |

2014- 2015 |

2015- 2016 |

2016- 2017 |

2017- 2018 |

2018- 2019 |

2019- 2020 |

2020- 2021 |

2021- 2022 |

TOTAL |

| 0-15 Days | 104 | 618 | 77 | 30 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 842 |

| 16-25 Days | 181 | 1,649 | 311 | 84 | 23 | 16 | 5 | 81 | 5 | 2,355 |

| 26-60 Days | 532 | 2,544 | 420 | 497 | 196 | 125 | 59 | 35 | 17 | 4,425 |

| 61-80 Days | 1,018 | 706 | 289 | 219 | 110 | 68 | 59 | 29 | 8 | 2,506 |

| 81-150 Days | 1,374 | 606 | 505 | 464 | 515 | 276 | 158 | 87 | 33 | 4,018 |

| 151-300 Days | 679 | 961 | 688 | 710 | 1,492 | 1,637 | 711 | 203 | 50 | 7,131 |

| 301+ Days | 161 | 1,803 | 1,735 | 758 | 303 | 430 | 952 | 192 | 0 | 6,334 |

| TOTAL | 4,049 | 8,887 | 4,025 | 2,762 | 2,644 | 2,556 | 1,946 | 627 | 115 | 27,611 |

TABLE 4. TOTAL NUMBER OF HIGH PRIORITY FINAL GRIEVANCES COMPLETED BY WORKING DAYS TO COMPLETION

| DAYS TO COMPLETION |

2013- 2014 |

2014- 2015 |

2015- 2016 |

2016- 2017 |

2017- 2018 |

2018- 2019 |

2019- 2020 |

2020- 2021 |

2021- 2022 |

TOTAL |

| 0-15 Days | 35 | 1 | 11 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 66 |

| 16-25 Days | 4 | 16 | 70 | 48 | 9 | 9 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 160 |

| 26-60 Days | 127 | 60 | 175 | 258 | 84 | 40 | 32 | 15 | 9 | 800 |

| 61-80 Days | 219 | 45 | 161 | 79 | 59 | 29 | 21 | 10 | 6 | 629 |

| 81-150 Days | 312 | 228 | 247 | 137 | 222 | 93 | 37 | 31 | 10 | 1,317 |

| 151-300 Days | 121 | 352 | 179 | 173 | 410 | 509 | 202 | 67 | 17 | 2,030 |

| 301+ Days | 46 | 412 | 559 | 259 | 86 | 134 | 377 | 51 | 0 | 1,924 |

| TOTAL | 864 | 1,114 | 1,402 | 967 | 872 | 816 | 671 | 174 | 46 | 6,926 |

TABLE 5. TOTAL NUMBER OF GRIEVANCES IN 2022-23, BY LEVEL AND DECISION

| GRIEVANCE DECISION | COMPLAINT | INITIAL | FINAL | GRAND TOTAL |

| Withdrawn | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Rejected – Not Made in Good Faith | 6 | 3 | 0 | 9 |

| Rejected – Not Within the Jurisdiction of CSC | 13 | 5 | 3 | 21 |

| Rejected – Vexatious | 36 | 5 | 1 | 42 |

| Rejected – Frivolous | 71 | 4 | 0 | 75 |

| Rejected – Otherwise Addressed | 81 | 18 | 14 | 113 |

| Resolved Through ADR | 155 | 1 | 1 | 157 |

| Beyond Authority | 184 | 22 | - | 206 |

| Rejected – Other | 140 | 110 | 12 | 262 |

| Upheld | 353 | 63 | 116 | 532 |

| No Data | 299 | 30 | 239 | 568 |

| Upheld in Part | 491 | 157 | 224 | 872 |

| No Further Action Required | 3,277 | 435 | 425 | 4,137 |

| Resolved | 3,899 | 640 | 842 | 5,381 |

| Denied | 4,729 | 1,867 | 1,114 | 7,710 |

| GRAND TOTAL | 13,738 | 3,360 | 2,991 | 20,089 |

An Investigation of Quality of Care Reviews for Natural Cause Deaths in Federal Custody

In 2014, the Office published a public interest report, titled, An Investigation of the Correctional Service of Canada’s Mortality Review Process. This report was triggered by successive decisions taken by the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) between 2005 and 2009 to reduce the administrative burden of conducting national investigations under section 19 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA), where deaths in custody were attributable to natural causes. As of 2009, the responsibility for conducting investigations into deaths resulting from natural causes changed hands from CSC’s Incident Investigations Branch to the Health Services Sector at National Headquarters.

My predecessor’s findings concerning the old mortality review process (MRP) were unequivocal, calling it “flawed and inadequate” and not conducted in a timely and rigorous manner as required by law. Further, the MRP failed to “thoroughly establish, reconstruct or probe the factors that may have contributed to the fatality under review.”:

For reasons that largely serve administrative convenience and expedient ends, the mortality review process was created as an ‘alternative’ to the formal Board of Investigation exercise. The process does not meet minimum standards for an investigative process or satisfy CSC’s statutory duty to investigate fatalities regardless of cause. It certainly does not respect the immediacy and urgency that is written into the ‘forthwith’ clause of the statute that governs the Service. As such, the process exists somewhere on the margins of the law; even its Guidelines do not yet have the force or effect of a policy directive within CSC.Footnote 24