June 30, 2016

The Honourable Ralph Goodale

Minister of Public Safety

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 43 rd Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Howard Sapers

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigator's Message

1. Health Care in Federal Corrections

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

Special Focus on the Use of Inflammatory Agents in Corrections

5. Safe and Timely Community Reintegration

Correctional Investigator's Outlook for 2016-17

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Annex A: Summary of Recommendations

Correctional Investigator's Message

The Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) , enacted in 1992, enshrined the principles of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in correctional law and entrenched the role of the Office of the Correctional Investigator in legislation. Part III of the CCRA gives the Office broad authority to serve as an ombudsman for federally sentenced offenders and investigate offender complaints related to decisions, recommendations, acts or omissions of Correctional Service of Canada (CSC). When reviewing complaints, the Office determines whether the CSC has acted fairly, reasonably and in compliance with law and policy. Impartiality and independence, principles that are protected in the enacting legislation, are the source of the Office's influence and credibility with the Correctional Service, Parliamentarians and the public.

The Office is an oversight, not an advocacy body; my staff do not take sides when investigating complaints against the Correctional Service. We conduct investigations and make recommendations to ensure safe, lawful and humane correctional practice. Ensuring accessibility is fundamental to the Office's mandate. A regular presence in federal penitentiaries helps ensure follow-up and timely access to Ombudsman services. Some of the Office's most important and impactful work occurs at the institutional level through the everyday resolution of issues, complaints and concerns.

Howard Sapers

Correctional Investigator of Canada

Through the reporting period, the Office's staff complement of 36 full-time equivalent employees handled more than 6,500 offender complaints. Investigators spent more than 370 cumulative days visiting institutions across the country, and conducted close to 2,200 interviews with offenders. The Office's use of force team reviewed more than 1,800 incidents its highest workload ever. Additionally, nearly 200 mandated reviews of serious bodily injuries and deaths in custody were completed. Intake staff handled 25,600 toll-free phone contacts logging close to 2,000 hours on the Office's toll-free line. I am constantly impressed by the remarkable volume of work that comes to the Office and the quality with which it is completed. I am grateful for the degree of professionalism and excellence displayed by my small and dedicated team.

This report is intended to serve as a summary of that collective output, a reminder not only of what has been accomplished through an especially productive reporting year, but also a reflection on systemic areas of concern where further progress and reform are necessary. A number of issues and trends stand out in the consideration of this year's report, among them include:

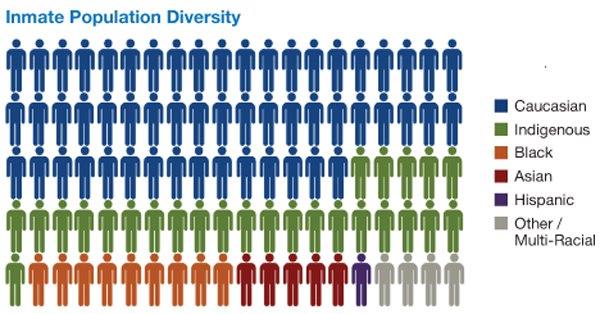

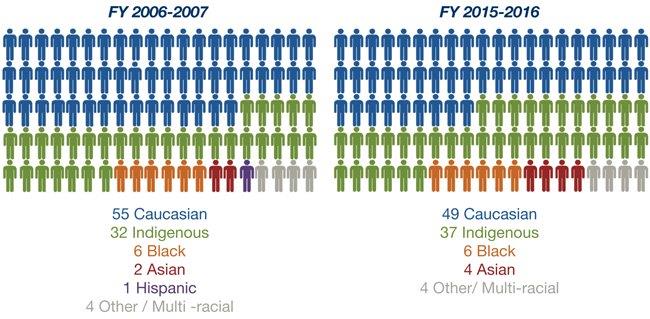

- An unabated increase in the number of Indigenous people behind bars, a rate now surpassing 25% of the total federal incarcerated population.

- The reliance on and escalating number of use of force incidents involving inflammatory agents.

- The demonstrated but unfulfilled need for more vocational and skills training programs in corrections.

- Continuing decline in the quality and rigour of case management practices.

- Inadequate progress in preventing deaths in custody.

- Alternative service delivery arrangements for significantly mentally ill offenders.

Most of these concerns are not new. If anything, they suggest acceleration or deepening of trends that have been with us for some time. We know that the rate of mental illness is higher in the inmate population compared to general society and recent research confirms that federal offenders are prescribed psychotropic drugs at a rate that is almost four times higher than the general Canadian population. Almost two-thirds of male offenders report using drugs or alcohol on the day of their current federal offence. For the seriously mentally disordered and addicted, a sentence of imprisonment has become the contemporary equivalent of being sent to the asylum.

In January 2016, the Office reported that the number of Indigenous people in Canadian penitentiaries had just reached 25% of the total inmate population. For federally sentenced Indigenous women, their representation rate now exceeds 35% of the in-custody women population. Of course, disproportionate rates of contact and conflict with Canada's criminal justice system are nothing new for Indigenous Canadians. As the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) most recently reminds us, these issues manifest from the lingering effects of the residential schools, the legacy of Reserves, higher rates of substance abuse, poverty, sub-standard housing in Aboriginal communities and a continuing high rate of contact with child welfare and protection systems. Unfortunately, these are the roots and feeders of a federal correctional system which disproportionately holds Indigenous people longer and at higher security levels than their non-Aboriginal counterparts.

I am encouraged by the present Government's stated commitment to implement the TRC's Calls to Action , several of which, including eliminating the overrepresentation of Aboriginal people and youth in custody over the next decade, link directly to corrections. Ending the cycles of intergenerational violence, abuse and discrimination that bleed into our jails and prisons will require vision, leadership and sustained focus and action. It is yet another reason why I again call on the Correctional Service to do the right thing and appoint a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections, a position and person who can provide the kind of focused direction and accountability required to realize TRC commitments.

In looking back over the past decade, I am particularly concerned by how changes to the Corrections and Conditional Release Act have been incorporated into policy and translated into practice. Introduced in March 2012, the Safe Streets and Communities Act made several significant changes to the purpose and principles of federal corrections. For example, principles typically reserved for sentencing such as the nature and gravity of the offence and the degree of responsibility of the offender were parachuted into correctional law suggesting that it is somehow appropriate to manage offenders based not on their level of risk or need, but on the severity of their crime. Corrections is supposed to administer the sentence challenge and change attitudes and behaviour that lead to criminal conduct not add to it.

Several other principles were muted or abandoned such as proportionality and restraint in the use of imprisonment gave way to other objectives, usually framed in terms of the pre-eminence of public safety. The reference to inmate privileges was removed from correctional law. Other long-standing principles, such as the least restrictive measure, were replaced with more ambiguous and elastic language that included proportionate and necessary measures. The notion of offender accountability became political shorthand for a series of legislative initiatives that effectively increased the severity of the sentence or the length of time spent in custody.

Perhaps the most significant change to the CCRA has been the incorporation of the paramount consideration principle, a new section which immediately follows the purpose statement of the federal correction system. This section provides that the protection of society is the paramount consideration for the Service in the corrections process. This change suggests that other equally valid correctional objectives, such as reintegration and rehabilitation, are at odds with the protection of the public.

Considered together, these changes to the principles of federal corrections reflect little tolerance for even well-managed risk. The odds are now firmly stacked against early discretionary release (day and full parole) and in favour of presumptive or statutory release (two-thirds point of the sentence). CSC is making fewer recommendations for release to the Parole Board of Canada. The number of offenders accessing the community through temporary absences and work releases fell to new lows again last year.

To be clear, the protection of society is a legitimate public policy objective for our correctional system, but it does not serve us well to have it stand as an over-riding principle. Canada's federal correctional system is founded upon a dual purpose mandate: to exercise safe and humane custody and supervision of offenders and to assist their timely return the community as law-abiding citizens. Experience and evidence tell us that the protection of society is the outcome of safe and effective correctional practice. We should not confuse or replace correctional purpose with principles.

The recent past teaches us that Canada's custody and release machinery does not optimally function in an administrative, legal or policy environment where there is little tolerance for error or risk. Deciding to release an offender to the community continues to require sound judgment and the active involvement of the case management team. When done properly, corrections contributes to prosperous and safe communities. Delaying or denying release to statutory or warrant expiry does not in and of itself lead to gains in public safety. Although correctional principles have been changed, the goal of preparing and assisting offenders for safe and timely reintegration remains.

Our correctional system is premised on the idea that the rule of law follows offenders into prison. It is guided, shaped and underwritten by constitutional rights and freedoms. It is my hope that this fundamental truth is at the forefront of the promised Criminal Justice review.

In closing, I welcome the government's commitment to openness and transparency. However, corrections is one area of public administration that is far from open by default. Prisons and those who administer them tend to operate largely closed to public view or scrutiny. In a robust and vibrant democracy, independent oversight, external review and outside intervention by assurance providers, the courts and Parliament continues to be necessary in ensuring Canada's prison system is safe, lawful and accountable.

Executive Director's Message

It has been another productive and busy year for the Office. Through the reporting period, the Office embarked on a comprehensive strategic planning exercise to review and renew the Office's priorities and work processes to ensure they remain relevant and responsive to the organization's mission and mandate. The resulting Strategic Plan 2015-2020 provides corporate direction and focus, integrating and aligning the Office's work within Blueprint 2020 and Destination 2020 activities, as well as the results of 2014 Public Service Employee Survey (PSES). This plan provides an opportunity for enhanced and effective delivery of the Office's important mandate.

Highlights and accomplishments which contributed to the strategic planning exercise included:

- The working group on Technology and Innovation submitted its final report with recommendations on technologies to assist and improve the delivery of the Office's mandate.

- An action plan was developed by an external consultant to deal with issues raised by staff response to the PSES. All items on the action plan were fulfilled over the year and will continue to guide the work of the organization over the long-term.

- A mid-year two-day strategic planning retreat was held where staffing streams (Intake, Investigators, Policy and Corporate) presented their role, function and suggestions for improving workload and processes.

- The Office's new shared case management tool is on track with roll-out planned for April 2017.

The Office also offered continuous learning sessions on Inuit Cultural Awareness, Aboriginal colonization, privacy, informal conflict management and mental health awareness. The coming year will be defined by an ambitious agenda as the Office moves forward with implementing key activities identified in the Strategic Plan.

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Executive Director and General Counsel

OCI by the Numbers 2015-2016

- $4.3 M budget

- 358.5 days spent in penitentiaries

- 6,500 offender complaints

- 2,196 interviews with offenders and staff

- 1,833 use of force reviews

- 196 deaths in custody and serious bodily injury reviews

- 25,600 toll-free phone contacts

- 1,918 hours on toll-free line

Federal Corrections in Context 2015-16

Total inmate population: 14,615 (Average Daily Count)

$111,202

Average Annual Cost (2013-14) of Incarcerating a Male Inmate

(Women Inmates cost twice as much)

1 in 4

inmates are Indigenous

(36% of women inmates are Indigenous)

1 in 4

inmates are over the age of 50

Almost 60%

of inmates are classified as medium security

1 in 5

inmates are serving a life sentence

More than Half

of all women inmates have an identified mental health need

(compared to 26% of male inmates)

4 in 10

inmates are serving a sentence of 2 to 4 years

1. Health Care in Federal Corrections

Context: Health Status of Offenders

Physical Health

A recent review of the social determinants of health among all Canadian prisoners (federal/provincial/territorial) concluded that the health status of this population is poor compared with the general population across a range of indicators including mortality, mental health, substance use, communicable diseases, and sexual and reproductive health Footnote 1 . Key findings of this clinical review include:

- Most persons in custody have experienced substantial adverse events in childhood (e.g. witnessing family violence or being involved with the child welfare system); at least half report a history of childhood physical, sexual or emotional abuse.

- The socio-economic status of this population is low, as indicated by substandard housing, low employment rates, low educational achievement and low income status.

- A disproportionate number of persons die in custody; rates of suicide and homicide are particularly high compared to the general population.

- Most persons in correctional facilities have mental health and/or substance abuse disorders.

- More than two-thirds of adults in Canadian custody are current smokers.

Recent CSC research confirms a number of the key findings of the independent clinical review that federal offenders experienced social determinants associated with poorer health outcomes over the course of their life such as poverty, low educational attainment, substandard housing and underemployment. Two social determinants in particular were consistently related to poorer health among federally sentenced men: history of childhood abuse and the use of social assistance. Footnote 2 Other studies point to higher incidence of chronic illness, infectious disease, premature mortality and health risk among offender populations, including high prevalence of concurrent addiction and mental health disorders.

Mental Health

A recent study of the prevalence of psychotropic medications behind bars found that these drugs were more commonly prescribed to federal offenders than in the general Canadian population (30.4% vs. about 8.0%). Footnote 3 Considerably more federally sentenced women than men had an active psychotropic medication prescription (45.7% for women and 29.6% for men). The study found that it was also relatively common for offenders to have more than one active psychotropic medication prescription. Overall, 17.3% of offenders had an active prescription for one psychotropic medication, 8.2% had two, and 4.9% had three or more. The most common psychotropic medication prescription category was antidepressant agents. Though psychotropic drugs are prescribed to federal inmates at a rate that is close to four times more than the Canadian average, the study contends that it is commensurate with similar correctional jurisdictions. Consistent with higher prevalence rates, women offenders were more frequently prescribed psychotropic medication than male offenders.

This study, which responds to some earlier concerns raised by the Office with respect to high percentage of women offenders prescribed psychotropics, is important as it provides further evidence toward establishing baseline prevalence rates for major mental health illnesses among federal offenders. For example, in 2014-15, CSC reported that 27.6% of the incarcerated population had mental health needs (defined as having had at least one mental health treatment-oriented service or stay in a treatment centre during the previous six months). Footnote 4 This percentage accords with the rate of offenders flagged by the Service at intake as requiring further mental health assessment. Previous sampling of incoming male offenders indicate the following prevalence rates: mood disorders 16.9%, alcohol or substance use disorders 49.6%, and anxiety disorders 29.5%. Lifetime disorder rates for borderline personality disorder were 15.9% and for antisocial personality disorder 44.1%. Footnote 5 By any measure, these rates far exceed those found in the general population.

The findings of these different studies and reviews converge on two important and related points: i. health status information is critical for defining areas of focus for improving correctional-based health care and; ii. time in custody offers a unique opportunity to intervene to improve offender health, with potential benefits for all Canadians such as decreasing health care costs, improving public safety and decreasing re-incarceration. Treating communicable diseases like Hepatitis C and offering a full range of harm reduction measures in prison helps reduce overall incidence and burden of disease and lessen public health risk. Full implementation of an electronic medical records system in federal corrections, which includes an ePharmacy solution to address drug inventory, control and distribution within CSC's regional pharmacies, should represent a major leap forward in strengthening correctional health care planning, evaluation and overall service delivery linked to offender health status and need.

Role of Health Care Providers in Corrections

The expanding involvement of health care professionals in matters that are outside their immediate and respective medical authority is troubling. The Office takes particular exception to the expanded advisory' role that health care professionals are now expected to play in segregation review boards. It seems improper for health care workers to be involved in the decision to maintain an offender in administrative segregation while maintaining a therapeutic relationship with that inmate

In the Office's review of use of force incidents, we question the nature and quality of post use of force psychological and health care assessments that are limited to visual inspection versus physical examination. These assessments are very often cursory in nature, limited to a few simple questions, conducted outside cell doors or through physical barriers, including food slots in isolation, segregation and observation cells. It is particularly instructive that more than half of the 1,800 plus use of force reviews conducted by the Office in 2015-16 indicated deficiencies with the post-use of force health care assessment.

At issue is the changing policy, administrative and operational context in which health care services are being provided. There is a pervading feeling of mission creep,'co-optation of health care workers in service of operational interests at the potential expense of patient needs. Paradoxically, the situation appears to have deteriorated even as the reporting relationships and accountability structures for health care workers were brought under the fold of the Health Services sector rather than operations. In recent years, CSC health services have underwent considerable and consequential changes. Many of these changes, including the implementation of the Refined Model of Mental Health Care for mental health service delivery, are still being rolled out. Health care policies across the board have been re-written, condensed, re-promulgated and implemented, but there has perhaps not been enough attention paid to how this constant state of flux and change has impacted scopes of practice, professional autonomy and patient advocacy on front-line service delivery. Whatever the source of these role conflicts and ethical dilemmas, it appears timely for these matters to be frankly discussed and debated among correctional health care professionals and their regulatory and licensing authorities.

- I recommend that CSC consult with professional colleges, licensing bodies and accreditation agencies to ensure operational policies do not conflict with or undermine the standards, autonomy and ethics of professional health care workers in corrections.

Aging and Dying Behind Bars

As the offender population ages behind bars, the frequency of chronic diseases and conditions requiring specialized and expensive treatment, up to and including palliation, is growing. In 2015-16, there were 38 deaths recorded in CSC facilities attributed to natural causes. The average age of natural death was 62. The Parole Board of Canada received 28 Requests for Royal Prerogative of Mercy in 2014-15 none were granted. As I have previously reported, the rising number of natural cause and/or premature death behind bars requires answers and some clear public policy direction. Federal penitentiaries were never intended to serve as hospitals or hospices. The Office continues to believe that there are better, safer and less costly options in managing an age cohort that poses the least risk to public safety yet is the among the most expensive to incarcerate. At one Ontario institution, more than half of the inmate population is age 50 or older. There are four dialysis machines running at this facility. Despite the growing need, there is still no national strategy to address the health care concerns of the of the inmate population that is now aged 50 or older.

- I recommend that CSC develop, publicly release and implement an older offender strategy for federal corrections in 2016-17 that addresses the care and custody needs of offenders aged 50 or older. This strategy should include programming, reintegration, public safety and health care cost considerations.

Access to Dental Care

Through the reporting period, the Office received increasing numbers of inmate complaints relating to access to dental care in CSC facilities. The source of these complaints stems from a decision to stop providing what the Service calls non-essential dental services. As of April 2014 the annual expenditure on dental services was reduced by just over $2M, which represents a reduction of more than 30% in spending on dental health care in the two year period between 2012-13 and 2014-2015. The predictable impacts of this short-sighted decision are beginning to be felt across the country.

Driven by short-term cost reduction goals, dental services are now prioritized according to the perceived level of need and severity emergency, urgent or routine. According to CSC, giving priority to inmates with the highest level of need will allow CSC to more carefully manage its resources. In many institutions, only the most severe or urgent cases are being treated. For example, inmates were previously provided complete oral examination and treatment planning once per year. This timeframe has now been extended to once every five years. Routine (or non-essential) cases are added to already long waitlists that can take several months before care is provided. Inmates in more remote institutions have reported to the Office that they have little or no access at all to dental services as there is no provider currently on contract. These complaints raise legitimate concerns that CSC is failing to meet its obligation to provide adequate access to essential dental health care.

Across the country, institutions are able to offer only a limited number of dental clinics in a given year, and contract dental professionals are increasingly required to prioritize inmates with more pressing dental needs over those with more routine or preventative care requirements. In institutions where dental care is extremely limited, due to a lack of dental professional contract or demand for services that far exceeds capacity, several Chiefs of Health Care are reporting that service provision standards are routinely not met. In some institutions, Escorted Temporary Absences (ETAs) are becoming the only care option for inmates whose dental needs are less pressing or include non-essential services. Reliance on ETAs for dental care provision is particularly concerning given the current set of challenges of providing community escorts in a timely manner due to conflicts with other operational priorities, cost constraints and staffing realities.

It can be expected that this short-sighted approach to generating modest savings will eventually lead to higher avoidable costs over the longer term as non-priority or routine issues develop into progressively more serious or emergency cases. In some sites, there has been a higher acuity in the list of inmates waiting to see the dentist as conditions such as abscesses develop. This causes a long delay for those who are not necessarily highly acute. Extraction may become the routine course (and cost) of dental treatment in CSC facilities, which clearly does not meet the Service's duty of care.

- I recommend that CSC create a national action plan to address dental waitlist concerns, restore funding for preventative dental health care and improve access to dentistry services in federal penitentiaries.

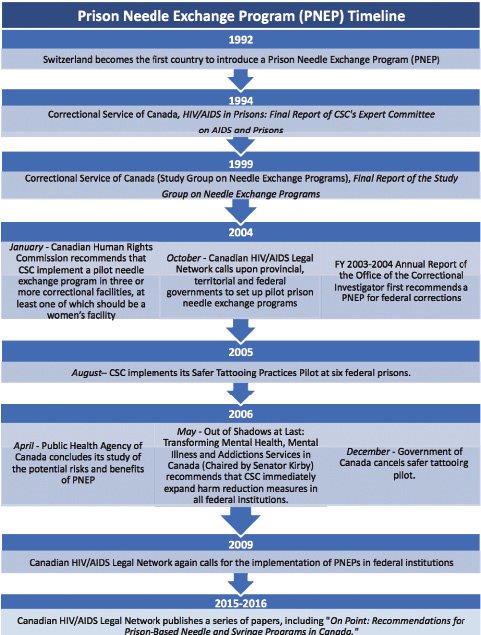

A Comprehensive Harm Reduction Strategy

Blood-borne infections are much more prevalent among offender populations. Over the past number of years, the Office has repeated calls for the CSC to explore a more comprehensive set of harm reduction measures that would more broadly mirror what is available and practiced in the community. Among others, such a strategy behind bars would include re-introducing safe tattooing sites and implementing a prison-based needle exchange program. Access to these measures in prison is both a public health and human rights issue. For example, the United Nations Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners (1990) states that Prisoners shall have access to the health services available in the country without discrimination on the grounds of their legal status.

Since first established in Switzerland more than 20 years ago, prison needle exchange programs have been implemented in a number of prisons and correctional jurisdictions throughout the world. Evidence has shown that, similar to those in community-based settings, prison-based needle exchange programs have proven effective in reducing the spread of infectious blood-borne diseases that arise through needle-sharing, increasing the number of offender referrals to drug treatment programs and reducing the need for health interventions related to over-dose incidents. Footnote 6 With proper controls in place, needle exchange and safe tattooing programs in prison do not jeopardize the safety and security of staff, inmates or the institution. CSC has already demonstrated that safe tattooing sites can be effectively implemented in federal corrections to the benefit and interests of the health and safety of staff, inmates and the general public alike.

- I recommend that CSC enhance harm reduction initiatives including the re-introduction of safe tattooing sites and the implementation of a needle exchange pilot and assess the impacts of these measures on inmate health, institutional substance miss-use and security operations.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder

In my 2014-15 Annual Report, I reported on the estimated prevalence of FASD in federal corrections as anywhere between 10% and 23%, and the fact that the CSC does not have a reliable or validated system to screen, assess or diagnose this spectrum disorder at intake. Footnote 7 The lack of reliable prevalence data means offenders with undiagnosed FASD may not be benefitting from specialized interventions that take into account an offender's mental health needs, as per legal requirements. As the emerging research on this segment of the offender population makes clear, the correctional environment presents unique and significant challenges for FASD-affected individuals, many of whom may find it difficult to self-regulate, adhere to penitentiary rules, demonstrate respect for authority or learn from past mistakes.

Last year, I recommended that CSC establish an expert advisory committee to provide advice on screening, assessment, treatment and program models for FASD-affected offenders. The Service responded that all offenders are eligible for specialized treatment and supports regardless of whether they have a confirmed diagnosis of FASD or not. Notwithstanding, CSC agreed to undertake an assessment of the need for such a committee. Though I have yet to hear back from the Service on its intentions to form an advisory group, I was happy to make contact with a community-based group Central Alberta FASD Network that has partnered with Bowden Institution to create a collaborative, integrated and multidisciplinary approach to assessing suspected FASD-affected offenders and supporting them on their release. The program already captures best practice guidelines and should be replicated across the country.

Case Study

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder Best Practice Guidelines for Corrections

Institutional Corrections

- Increase staff training, strategies, and awareness of working with FASD-affected individuals.

- Enhance admission screening and assessment criteria for cognitive deficits / disorders

- Expand FASD-adapted program delivery models and capacity

Community Corrections

- Provision of supportive and safe housing.

- Access to meaningful employment.

- Consolidation of family and / or community supports and services.

- I recommend that CSC work collaboratively with community groups that have proven expertise in providing treatment services and supports for FASD-affected individuals to address significant gaps in assessment, programming, treatment and services to these offenders in federal corrections.

Transgender Inmates

The Office remains concerned that CSC's policy framework for transgender inmates (Guidelines 800-5 Gender Dysphoria ) is outdated and puts this group at elevated and unnecessary risk. Currently, transgender inmates who have not had sex reassignment surgery are held in institutions that correspond to their biological sex. This practice means that pre-operative transgender women prisoners in federal custody are forced to live in men's institutions. They may be placed in institutions or situations where they are vulnerable to sexual harassment or assault.

Moreover, under current policy, pre-operative transgender inmates are only eligible for surgery after spending one year living as a transgender person in the community not in prison. CSC policy further requires that it proceed without delay to determine the timing of the approved surgery (which is an essential medical service) taking into account operational considerations and the offender's release date. The effect of this policy is discriminatory and inconsistent with community health care standards as most pre-operative transgender inmates will never practically satisfy the one-year real-life' experience test required by CSC.

Federal correctional policy does not adequately reflect the current and evolving state of domestic and international law protecting the rights of transgender people who are imprisoned. The most recent Standards of Care for Transgender People (2011) indicate that transgender people should not be discriminated against in their access to appropriate health care based on where they live, including institutional environments such as prison.

- I recommend that CSC's gender dysphoria policy be updated to reflect evolving legal and standards of care protecting the rights of transgender people in Canada. Specifically:

- upon request and subject to case-by-case consideration of treatment needs, safety and privacy, transgender or intersex inmates should not be presumptively refused placement in an institution of the gender they identify with.

- the real life' experience test should include consideration of time spent living as a transgender person during incarceration.

Update on CSC's Response to the Ashley Smith Inquest

CSC responded to the Coroner's recommendations into the death of Ashley Smith on December 11, 2014, one year after the inquest reported and seven years after Ashley died in a segregation cell at Grand Valley Institution for Women in October 2007. At that time, I observed that CSC's response was frustrating and disappointing. That assessment stands.

The jury's final recommendation stated: That the Office of the Correctional Investigator monitor and report publicly, and in writing, on the implementation of the recommendations made by this jury annually for the next 10 years. Since most of the recommendations were not answered individually, much less substantively, there seems little practical value in my Office issuing an annual public progress report. I would simply note as an update that the Government has committed itself to implementing outstanding recommendations from the inquest, including those regarding the restriction of the use of solitary confinement and the treatment of those with mental illness.

I specifically look for movement on key health care measures identified by my Office and at the inquest. Among these I would include:

- Prohibit long-term segregation of mentally dis-ordered offenders.

- Commit to move toward a restraint-free environment in federal corrections.

- Appoint independent patient advocates at each of the Regional Treatment Centres.

- Provide for 24/7 on-site nursing services at all maximum, medium and multi-level penitentiaries.

- Develop policies and practices to address the unique needs of younger offenders.

Progress on these important issues would demonstrate that the lessons from Ashley Smith's tragic and preventable death have indeed been learned and, more importantly, acted upon.

CSC's Response to Self-Injurious Behaviour

In February 2016, the Office received a consultation request informing of CSC's intent to revise Commissioner's Directive 567 Management of Security Incidents and the Situation Management Model (SMM) . The Policy Bulletin accompanying the consultation request noted that the policy has been modified in relation to the Response to the Coroner's Inquest Touching the Death of Ashley Smith (December 2014).

At the Ashley Smith inquest, CSC was urged to explore alternative front-line response models for managing difficult, complex and challenging self-injurious behaviours. Specifically, the jury made two recommendations relevant to the Commissioner's Directive in question:

- That CSC develops a new, separate and distinct model, from the existing Situation Management Model, to address medical emergencies and incidents of self-injurious behaviour.

- That the Situation Management Model not be resorted to in any perceived medical emergency.

In making these recommendations, the jury recognized that first response correctional officers are not mental health professionals, nor do they necessarily have the tools, training or resources to safely defuse situations where an inmate is in acute psychological or medical distress.

In an exchange of correspondence with the Office, CSC stated that, based on its analysis, the SMM remains fundamentally sound and that medical emergencies, incidents of self-injurious behaviours and offenders with mental health disorders are situations that are appropriately covered in the SMM. In other words, the CSC was rejecting the specific recommendations from the Ashley Smith inquest.

In reaching this conclusion CSC relied on consultations undertaken with the Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police, the RCMP and other stakeholders, mostly or entirely drawn from the law enforcement community. My Office was not included in this consultation nor, evidentially, were any mental health professionals or experts working in the forensic or psychiatric fields. The result of the consultation was predictable. Instead of developing a new, separate and distinct model for addressing mental health and self-injurious behaviour in CSC facilities, the revised policy simply opts to add these components to the list of situational factors to be considered when staff are formulating a response to a self-injurious incident. Beyond requiring non-clinical staff to take into account an inmate's mental state and ability to comprehend direction, the review of the SMM seems to have yielded little in the way of new policy direction or alternative approaches to managing self-injurious incidents in CSC facilities.

For a number of years, the Office has encouraged CSC to treat and respond to self-injurious behaviour as a mental health not security issue. Absent further policy direction or alternative response protocols (such as requiring a mental health professional to provide a therapeutic response while security staff remains in the background ready to intervene if required), the proposed revisions are unlikely to change what has become, since Ashley Smith's death, a predominantly security driven response to self-injurious behaviour, especially in higher security correctional environments.

When confronted with a self-injurious offender, the SMM requires staff to isolate and contain the threatening behaviour or situation as quickly and safely as possible. Non-clinical staff are trained and directed to respond as if all self-injurious incidents might result in accidental or intentional death. After verbal interventions fail, these situations can quickly escalate leading, in some cases, to some unhelpful or even punitive response options, up to and including the use of inflammatory agents, physical handling or restraints, disciplinary charges or placement in a segregation or observation cell. In some cases of serial self-injury, even the compliant application of the SMM can end up reinforcing or escalating the severity or lethality of the behaviour it seeks to contain or neutralize. Few of these outcomes can be considered desirable or appropriate from a clinical, human rights or even correctional perspective, which is precisely why a different, non-SMM, non-security focused approach is required. Isolation, containment and control the underlying principles of SMM intervention surely are not appropriate interventions for someone who is in psychological distress. There is a need for CSC to understand and address the conflicting goals of an SMM versus therapeutic response in situations of significant psychological or medical distress.

As things stand now, neither the revised policy nor the unchanged SMM provide sufficient guidance or scope for non-clinical staff to consider and apply principles to self-injurious behaviour informed by:

- The least restrictive option

- The most proportionate measure

- The most appropriate (humane and safe) intervention

- Clinical and/or dynamic risk assessment

An alternative response model would direct security staff to adopt a primary support role (i.e. ensuring everyone's safety) while the actual intervention, carried out by mental health professional(s), focuses on assisting the self-injurious offender. In correspondence to the Office, CSC stated that they share the OCI's concerns regarding mentally ill inmates and the use of force. Punishing people for behaviours and emotions that they may not be able to regulate or control does not indicate that CSC shares the Office's concerns. That is the point of trying a different model and approach to managing self-injurious incidents in a prison setting. That is what the jury at the Ashley Smith inquest recommended and that is what CSC should do.

- I recommend that CSC develop a new, separate and distinct model from the existing Situation Management Model to address medical emergencies and incidents of self-injurious behaviour in partnership with professional mental health organizations.

Management of Complex Mental Health Cases

CSC is managing an increasing number of complex mental health cases with overlapping needs, such as major mental illness, personality disorder, cognitive impairment, learning disorder, substance abuse, or combination of any of those. To monitor offenders who are experiencing significant mental health concerns, including those who engage in chronic, repetitive self-injurious or suicidal behaviour, the Service has put into place Regional and National Complex Mental Health Committees (NCMHC). The national level committee meets monthly. It is comprised of senior executives and is chaired by the Director General of Mental Health. In addition to receiving updates and monitoring the progress of complex cases, the Committee reviews business cases which are required to access national funding that has been set aside to assist in the treatment and management of approved cases. This funding may be designated to conduct external or independent psychiatric assessments.

From April 1, 2015 to February 8, 2016, a total of 215 offenders with complex mental health needs were monitored at the regional or national level. A number of these national-level cases were also the subject of review and intervention by this Office. They included a certified offender at a regional treatment centre who was subjected to repeated interventions by the Institutional Emergency Response Team in order to force compliance with medical treatment. This case was being managed by way of isolation, forced compliance, security and control without any clinical or therapeutic plan in place to treat underlying mental illness.

Another mentally ill male inmate was the subject of frequent transfers between maximum security facilities and treatment centres. He spent long periods in segregation where his chronic self-injurious behaviour was met by repeated use of force interventions. In still another case, a certified chronic self-injurious male offender accumulated numerous institutional charges at a Regional Treatment Centre while being physically restrained on a near continuous basis. In all three cases, the Office recommended transfer to an outside psychiatric facility for treatment and assessment and in each instance the CSC insisted that it could manage without external placements. These difficult and challenging cases continue to demonstrate the need for alternative service delivery options in federal corrections that would allow for transfers and placements of mentally disordered individuals in external psychiatric settings.

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety direct CSC to develop additional community partnerships and negotiate exchange of service agreements in all regions that would allow for alternative placement and treatment arrangements other than incarceration for significantly mentally ill federal offenders. These arrangements and agreements should be in place by the end of the current fiscal year.

Systemic Review of Complex Needs Cases at the Regional Women's Facilities

In 2015-16, the Office undertook a systemic review of 48 federally sentenced women whom the Service identified as meeting the requirements of a complex case and who were being monitored by the Regional and/or National Complex Mental Health Committees. Sixteen of the 48 women were monitored at the National level. Eight cases received complex case funding from National Headquarters (NHQ) to support the operational needs to support these women. Seventeen of the 48 women spent time in segregation over the past year, one exceeding 70 days.

One woman who was monitored at the regional and national levels died in federal custody due to her mental health problems. It was the first suicide at the regional women's facilities for several years. Although she was subject to regional and national monitoring, at the site level the institution did not receive any specialized complex case funding, despite the fact that her level of need and escalating degrees of self-lethal behaviour would appear to have met any diagnostic threshold.

Of those women who were identified as complex cases and for whom funding was provided, the Office could not readily decipher the value being added aside from the basic, consistent, and humane interactions that the extra staff provided. In some cases, funding was approved to conduct an external psychological assessment, however, there were no additional resources provided to help the institution implement the clinical measures recommended by the outside expert. The Office questions whether a mainstream institution is the right place to implement complex clinical plans; Regional Treatment Centres and external hospitals are more suitable therapeutic environments.

During site visits, investigators found that front line staff working with complex cases was often unaware that clinical management plans were in place to support offenders' complex mental health needs. This is a long standing concern compounded by the fact many of these women must be managed at the regional facilities due to lack of bed space at the Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC), CSC's only dedicated treatment facility for federally sentenced women.

There are a number of women who were being monitored at the regional and national level who sought treatment at the RPC but were denied for a variety of reasons. As an alternative to admission to a treatment centre, CSC can provide funding to support the complex case at the parent institution; however, the physical infrastructure of the secure environments at the regional facilities remains a challenge for adequate treatment. Nova and Fraser Valley Institutions for example, house secure women in two maximum security pods. Complex cases take up a great deal resources. When these women become dis-regulated, as they often do, they can have a significant impact on other women who are living with them.

Our Office spent considerable time in the maximum security Secure Units over the past year. Despite the best intentions of dedicated staff, the population pressures and limitation on the physical infrastructure provide few options for these women to access quiet time and benefit from therapeutic environments. For example, during one site visit, staff were simultaneously managing three complex cases in the Secure Unit, which consists of two pods housing approximately ten women. During this visit, the options for these women to access quiet time was the segregation range, the cement yard, the program room and/or interview room. Even when staff sought actively to accommodate the needs of the complex needs women, the routine of the Secure Unit could not offer meaningful access to a therapeutic environment.

Moreover, the other women living in close proximity to complex cases often become frustrated with the conditions of confinement that flow from the behaviour of the women who engage in chronic self-injury. They consequentially spend more time locked up as staff must secure the units to respond to the complex cases. They also indicate that their opportunities for work/programming are daily affected by various incidents related to the mental health problems of a few individuals. In fact, this was a common complaint from the women who live in the Secure Unit in two of the five women's facilities that were managing acute complex cases. The Office received numerous complaints related to ongoing cell re-locations, lock downs, cancelled programs, and general concerns related to the dis-regulated behaviour of the women who suffer from acute mental illness. The Office received similar feedback from other external stakeholders, who report that women are seeking quiet time in the administrative segregation unit just to escape the unfavourable conditions that prevail in pod living.

- I recommend that internally allocated specialized complex case funding should not be used as an alternative to seeking placement in an external treatment facility and that the CSC allocate funding for treatment beds commensurate with diagnostically identified needs.

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

The Office reviews all CSC investigations resulting in serious bodily injury or inmate death. In 2015-16, the Office conducted nearly 200 such reviews.

Reviews by Type of Incident

| Type of Incident | # |

|---|---|

| Assault | 43 |

| Attempt Suicide | 12 |

| Death | 5 |

| Death (Natural Causes) | 63 |

| Injuries | 31 |

| Murder | 1 |

| Overdose | 30 |

| Self-Mutilation | 2 |

| Suicide | 9 |

| Total | 196 |

New Reporting Format for Board of Investigations

Section 19 of the CCRA mandates that the Correctional Service investigate all deaths in custody as well as incidents resulting in serious bodily injury. During the reporting period, CSC adopted a new streamlined format for what is referred to as National Board of Investigation (or NBOI) reports. With a new focus on narration and story-telling, these changes ostensibly respond to a number of identified and perceived problems, namely that NBOI reports tend to be long, repetitive and too narrowly focused on compliance. Often completed many months (or even years) after the incident in question, access to the reports is restricted and they are not widely read.

The Office has often questioned the impact of section 19 investigations in correcting system-wide deficiencies. The same type of incidents are investigated over and over again with many of the same findings and concerns repeated from one investigation to the next. For example, a January 2016 lessons learned bulletin published by the Investigations Branch noted that, with respect to the theme of emergency staff response e.g. medical response, video recording on incident, initial response, adherence to emergency directives the timeliness, quality and completion of these sub-categories were identified as concerns, although quality was the greatest concern. Footnote 8 The Office identified these concerns nearly a decade ago in its first major deaths in custody study published in 2007.

The reasons behind the changes to the reporting format are of limited interest to the Office, however, some of them point to major issues in respect to the overall quality, comprehensiveness, and utility of these internal investigative reports. For example, the new reporting format provides much less detail on the manner in which the investigation was conducted, time spent on site or whether there were any difficulties in getting access to documents or witnesses. Persons interviewed and the documents consulted as part of investigation are also no longer included. Footnote 9 Other changes make it difficult for the Office to assess the investigative lines of inquiry pursued by the boards of investigation. Moreover, compiling a separate list of so-called secondary findings and setting limits on the length of the report, including the analysis section, may have a direct impact on the ability of board members to provide complete or adequate analysis of the issue under investigation. These changes effectively serve to further dilute or side-step the essential issue of accountability.

Over the last quarter of the reporting period, the Office received some very poor quality and less than thorough investigative reports. In one case, the report was so incomplete and inadequate that the Office recommended that the investigation be reconvened. In another case, the body of a deceased inmate was removed from his cell and left uncovered in the hallway for three and a half hours before the police and coroner arrived on the scene to investigate. Officers stood watch and walked over the body while conducting rounds, leading to concerns that a possible crime scene had not been properly secured and preserved. This finding was considered supplementary as it was determined not to have had a direct impact on the outcome of the incident.

The Office is particularly concerned that the new report format no longer allows for psychological reviews, which were mandatory for all investigations into prison suicides prior to the adoption of the new reporting guidelines. Produced by a mental health professional who was a member of the Board, these professional reviews were annexed to the investigation report. In September 2014, the Office's investigation of 30 inmate suicides that occurred in the three year period between 2011 and 2014 included a specific recommendation that:

Psychological autopsies conducted in the course of investigations into prison suicides should be expanded to determine possible underlying causes and comparative profiles of other inmates who had committed suicide.

In February 2015, CSC's response mentioned that although the psychological autopsy is a known approach to understanding suicide, there is no standard format for completing the process. For several years, CSC has been including the completion of a comprehensive psychological review as part of the mandate of every Board of Investigation into a suicide. Even though CSC did not consider these reviews to be psychological autopsies, in fact they followed a comprehensive and recognized format consistent with international practices in suicidology studies. These specialist reviews covered relevant and thorough case information regarding history of substance abuse and mental health issues, as well as specifics about depression, suicidal ideation, previous suicide attempts, and an evaluation of potential motivations, complete with sources of information for all elements. These elements brought the exercise within the expectations of a psychological autopsy. What is now called a Mental Health Review, this section can be conducted by any registered clinician, which includes registered or licensed nurses. Footnote 10 More importantly, the information gathered through the new review process and disseminated in the report is not as complete or exhaustive on many clinical or psychological aspects.

In summary, the Office accepts that NBOI reports could be more reader-friendly and we share a mutual interest in increasing their visibility and impact across the organization. However, in the interests of introducing a new reporting structure to better tell the story of the case under review, the new shortened reporting format may actually be a step backward in better understanding the specific risk and preventive factors for serious bodily injury or inmate death. While CSC has made some improvements since the first of these reports was issued in the new format, they continue to be problematic. The Office will be closely monitoring the impact on the overall quality, timeliness and comprehensiveness of internal investigations.

- I recommend that CSC retain, as a mandatory requirement, that a psychological review/autopsy be conducted by a registered mental health clinician into each and every prison suicide.

Third Independent Review of Deaths in Custody

In October 2015, the third Independent Review Committee (IRC) of Deaths in Custody reported their findings and recommendations on non-natural deaths (suicide, murder, overdose, accidents) that occurred in federal custody. Some familiar themes to this Office were reported by the independent reviewers:

A recurring, implicit theme in many of the Boards of Investigation reports was one of nothing could have been done to prevent this death' because he contracted for safety but took his life anyway' or he chose not to seek help, or he evidenced forward thinking, therefore his death was not preventable.' In closing, the findings of the Boards of Investigation conclude that the majority of the suicides could not have been prevented. This conclusion is inconsistent with the recent trends in the suicide literature. Footnote 11

Case Study

Key Findings of the Third Independent Review of Deaths in Custody

The IRC reviewed 23 of 46 non-natural deaths that occurred in CSC custody between 2011 and 2014. Of the 13 prison suicides independently reviewed, key findings include:

- 26% were in administrative segregation at the time of their deaths.

- In almost two thirds of these deaths [64%], there was an identifiable stressor in the offender's file.

- Ten of the thirteen (77%) individuals who committed suicide had prior identified mental health disorders.

- Only eight (62%) were documented to have received a suicide risk assessment. Six (75%) were deemed to be low risk and 2 (25%) were identified as moderate risk. None were identified as high risk.

- In nine (69%) of these cases there was a recording of a previous suicide attempt and in five cases (38%) there was a history of repeated self-harm that was not considered suicidal in nature.

The Boards of Investigation reports concluded that the majority of deaths by suicidecould not have been prevented.

Overall, the third IRC concludes that some prison suicides were preventable, if not predictable. The Committee notes that there is overall room for improvement in the areas of dynamic security, case management, suicide prevention and intervention, especially better assessment and closer monitoring of suicide risk factors. It makes the important point that non-suicidal self-injury (such as head-banging) is a risk factor for later lethality. The report also discusses prison suicides that occur shortly after hospital discharge and/or contacts with mental health professionals in prison. The Committee recommends that current assessment procedures (e.g. screening tools and clinical interviews for suicide risk) need to be revised considerably and the results clearly communicated to correctional staff at all levels of care. I concur.

With respect to prison suicide, the Committee reaches many of the same conclusions as this Office, particularly with regard to screening, assessment and identification of suicidal risk and/or intent. In and of itself, this concordance may not be all that surprising given that the IRC reviewed many of the same 30 suicides that were part of the Office's three year review of federal inmate suicides (2011-2014). That said, the failure to learn from repeated mistakes or make sustained progress over time has to be one of the most frustrating aspects of these reviews of reviews of deaths in custody. In September 2014, I concluded my own review of 30 prison suicides with this observation:

A major though incalculable obstacle to CSC's prevention efforts remains an organizational belief that prison suicides are rare, isolated or unexpected. In most post-incident reviews of prison suicides, there is a sense that nothing further could have been done to prevent a suicidal, mentally ill or self-injurious inmate with access to means and method from taking their own life. The impression remains that most suicide deaths in custody, however tragic or pre-indicative, are simply beyond the reach of current prevention or corrective measures.

Though the IRC report was perhaps less muted in its criticism, arguably its most unique and strongest contribution is to put into renewed question CSC's conclusion that the majority of prison suicides could not have been prevented. As the third IRC and my own Office document, there were either known immediate precipitating factors or other proximal circumstances or influences that indicated elevated risk or intent of suicide.

- I recommend that CSC publicly release the third Independent Review Committee report on deaths in custody and the action plan responding to the report's findings and recommendations.

Findings of the Office's Review of Prison Overdose Incidents

In the reporting period, the Office reviewed 85 investigation reports that involved 105 incidents of overdoses occurring in CSC facilities between 2012/13 and 2014/15. In conducting this review, the Office expected that, given the focus and enhanced measures in place to limit access to drugs and other contraband in federal penitentiaries, these investigative reports would be an important source of information to CSC management in determining whether drug interdiction efforts and resources are having the intended effect.

The intentions of the inmates involved in overdose are not easy to determine by retroactive investigations; some overdoses were deemed to be a suicide attempt, though the majority were determined to be accidental. In 11 cases, the result of the overdose was lethal. Only one of the fatal overdoses was retroactively determined to have been a suicide. Regardless of intent, in all cases these incidents were of sufficient seriousness to have warranted the Service to convene a board of investigation into their causes.

The inmate profile data gathered is informative but not necessarily representative. The majority of inmates involved in overdoses were aged between 30 and 49. Indigenous male inmates are slightly over-represented in overdose incidents, though four of the five women involved in overdose incidents were Aboriginal. In terms of risk profile, just over half of all inmates involved were serving their first federal sentence, and over two-thirds had served less than a year. Most incidents occurred in medium security facilities. Ontario and Prairie Regions accounted for the majority of overdose incidents. Though this review remains preliminary, key findings are summarized below.

- For overdose incidents involving men offenders, prescribed medications were the source of overdose in 31 cases and non-prescribed medications were the source in 10 cases (including two cases of methadone overdose).

- In 11 cases, Fentanyl was identified as the source drug of overdose, heroin was involved in 18 cases, opiates of unknown nature in 10 cases and the remaining involved cocaine, synthetic marijuana and drug cocktails.

- For the five women involved in overdoses, two incidents were categorized as suicide attempts. Prescribed medications were used in four of the five incidents.

- In incidents involving men, the overdose was self-reported in only 9 cases. In the other 91 incidents, the inmate was found in medical distress (either reported by other inmates or discovered during security rounds).

With respect to information contained in the 85 Board of Investigation reports that examined 105 incidents, the following findings are reported:

- The Board does not mention whether or not the inmate ever participated, was recommended or assessed for participation in substance abuse programming in

26 cases. - In 17 reports, the Board fails to mention whether or not the inmate involved had a history of suicide attempt or ideation.

- In 16 reports, the investigation does not mention whether the inmate had a history of mental health issues.

- In 55 of 105 incidents, the results for dynamic factors in substance abuse were not mentioned.

- In the 94 cases where death did not occur, the Board mentions that inmates were referred to substance abuse programs in only 10 cases. However, for most incidents, the report does not address or recommend referrals following overdose.

- In nine cases, the inmates involved were reclassified to higher security following overdose.

- There is no mention of whether the institution was in compliance with its search plan in 27 cases prior to the overdose. zIn 22 other cases, the institution was not compliant with its search plan.

As a follow-up, the Office will confirm and share the findings of our review of prison overdose incidents with the Service and request an action plan in response.

Update on CSC Public Reporting on Prevention of Deaths in Custody

In May 2015, I received CSC's inaugural Annual Report on Deaths in Custody 2013-2014 . Footnote 12 While the covering correspondence to the report indicates that it responds to an outstanding recommendation made in my report A Three Year Review of Federal Inmate Suicides (released September 10, 2014), in fact the original recommendation upon which it is based was first made more than five years prior in my 2009-10 Annual Report:

I recommend that the Service publicly release its Performance Accountability Framework to Reduce Preventable Deaths in Custody in fiscal year 2010-11 and that this document serve as the public record for tracking annual progress in this area of corrections.

Despite a number of attempts, the original recommendation was never satisfied, which is why I felt compelled to repeat it over the years, most recently in the Office's review of inmate suicides.

It is therefore surprising and disappointing that the ongoing focus and purpose of this work is either missing or misrepresented in the Service's Annual Report on Deaths in Custody . Devoid of context, there is not one single reference to any report, finding or recommendation of this Office or the Service's response. In fact, there is no discernible focus or direction to this report, no analysis or review of measures to be taken or no progress report. In an exchange of correspondence with the Commissioner on this matter, I indicated that the response was inadequate and deficient on these and three other related grounds:

- Though natural cause deaths are now the leading cause of mortality in federal corrections, the report shows little engagement, priority or understanding of the issue. It makes no serious attempt to identify or address the drivers behind the upward trend in natural mortality behind bars, most of which is now well-known to CSC e.g. aging inmate population, chronic illness/disease prevalence among an aging and institutionalized population, accumulation of long-serving/indeterminate sentenced offenders, untreated health conditions. The fact that inmates continue to die prematurely in CSC facilities on average between 60 and 62 years of age is not addressed.

- It appears that this document is meant to somehow replace the Annual Inmate Suicide Reports , which were discontinued after 2010-11. Even if the Service's intentions were to respond to my recommendation by simply providing an enhanced version of the moribund Annual Inmate Suicide Report , it still falls far short of the mark in terms of providing equivalent data, information and analysis. Social and mental health background, risks and pre-indicators of suicide, significant findings and recommendations from National Boards of Investigation, issues identified by Coroners, corrective measures aimed at mitigating organizational risk are not included.

- There is little indication that this report reflects an integrated perspective. It does not appear to have been widely shared or extensively vetted. For example, CSC's latest analysis of mortality reviews of deaths dating back to 2011 is not referenced, nor is the Service's response to the Ashley Smith inquest, though both efforts presumably fall within the reporting period. There is no analysis or reference to major findings from CSC's internal boards of investigation, no identification of corrective measures that have been implemented in the reporting period or how the present report will inform prevention efforts going forward.

Most important perhaps, the report fails to provide a set of key performance indicators and corporate plans that could be used to benchmark and assess the Service's progress in preventing future deaths in custody. At best, the first annual report serves as a statistical roll up of deaths that occurred in CSC facilities in 2013/14; it is not an accountability framework or a public progress report that would help the Service to transparently reduce, avert or prevent deaths in custody. I conclude that the intent of my recommendation has still not been met several years after it was first issued. The Annual Report on Deaths in Custody exercise is not complete, not credible and unresponsive to the recommendation it purportedly addresses. I expect to see these concerns addressed in CSC's subsequent public reports.

National Forum for Preventing Deaths in Custody

The lack of responsiveness, public transparency and accountability in CSC's overall effort and response to preventing deaths in custody is increasingly problematic. There is as much need today as there was when I first called for the creation of a national forum for preventing deaths in custody. This independent high level review and information sharing body would be empowered to monitor the number or rate of deaths in federal prisons, provincial and territorial jails, as well as law enforcement and immigration detention facilities. A National Forum, similar to the United Kingdom's Ministerial Council on Deaths in Custody, could be a complementary measure to the government's stated commitment to sign and ratify the UN Optional Protocol on the Convention against Torture (OPCAT). Footnote 13

The UK model is particularly instructive as it incorporates an independent and expert advisory body with Ministerial accountability. Canada would be well served by replicating a similar structure here, a measure which would send a strong signal about the importance of prevention of deaths in custody and implementing best practices. With respect to the OPCAT , inspection of all federal places of detention could benefit from a joined-up approach, combining other national policing (RCMP), immigration (CBSA), public safety (CSC), national defence and their respective review bodies. Establishing a national forum for prevention of deaths in custody similar to the UK model, together with the government's stated intention to sign the OPCAT, could be central mechanisms for enhancing Ministerial oversight across the entire Public Safety portfolio while demonstrating federal leadership with provincial and territorial partners.

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety work with provincial and territorial counterparts to create an independent national advisory forum drawn from experts, practitioners and stakeholder groups to review trends, share lessons learned and suggest research that will reduce the number and rate of deaths in custody in Canada.

3. Conditions of Confinement

Use of Force Reviews Conducted by the Office

The Office reviewed 1,833 use of force incidents in 2015-16, an increase of 22% over last year.

Issues of Concern

- Aboriginal offenders (25% of the population) accounted for 30% of all use of force incidents reviewed, which was similar to the previous fiscal year.

- Black offenders (10% of the population) accounted for 18% of all use of force incidents reviewed, an increase of 3% compared to last year.

- 14% of use of force interventions were in response to incidents of self-injury.

- 39% of all use of force incidents reviewed occurred in the offender's cell.

- 36.6% of all incidents involved offenders with a mental health issue identified by the Service. 40.95% of use of force incidents at CSC's treatment centres included the use of pepper spray.

- Overall, inflammatory agent(s) was used in 61% of all incidents.

- Compliance deficiencies:

- The Situation Management Model not followed in 10% of interventions reviewed.

- Decontamination procedures not followed in 31% of all incidents reviewed.

- Post-use of force health care assessments deficiencies noted in 54% of all reviews.

- Video recording procedures deficient in 77% of all reviews

- Strip search procedures were not followed in 30% of all interventions.

- Offenders alleged inappropriate levels of force used in 5% of all incidents reviewed.

Special Focus on the Use of Inflammatory Agents in Corrections

Introduction and Focus of Review

The Office reviews all use of force incidents occurring in CSC facilities. As per policy, CSC is required to provide all use of force documentation to the Office for review. This documentation typically includes:

- Use of Force Report

- Copy of incident-related video recording

- Checklist for Health Services Review of Use of Force

- Officer's Statement/Observation Report

- Offender's version of events

- Action plan to address deficiencies

The Office's review of use of force incidents over the past year has identified some concerning trends and new developments:

- Use of force incidents in CSC facilities are increasing.

- Increasing reliance on the inflammatory agents to gain inmate compliance, especially in higher security facilities.

- Persistent lack of policy compliance (i.e. lack of use of handheld camera, decontamination procedures, strip searches, post-health care assessments).

- CSC's use of force review framework fails to identify and correct systemic deficiencies.

In light of these trends, a thematic review of the increasing use of Oleoresin Capsicum (inflammatory, OC or pepper) spray in federal corrections was initiated during the 2015-16. The review included a trend analysis of all use of force reviews conducted by the Office, including a special focus on use of force in three maximum security facilities. The review also looked at CSC's internal use of force data to assess and compare incident-related trends against the Office's reviews.

Themes

Use of Force Incidents Involving Inflammatory Agents

Since 2011-12, the use of inflammatory agents has nearly tripled increasing from just over 500 to 1,443 uses in 2015-16. Footnote 14 The increase in use of force incidents can be largely attributed to the rising use of organic inflammatory agent, commonly referred to as OC (oleoresin capsicum) or pepper spray. The increasing resort to the use of these agents in use of force interventions suggests just how widespread reliance on this tool has become at the expense of other, more dynamic and less invasive responses.

When CSC staff encounters a situation (e.g. a self-injurious offender, an inmate fight, disruptive behaviour) any intervention used to manage or control the incident must be consistent with the Situation Management Model (SMM). According to CSC policy, the SMM is meant to: Footnote 15

- Promote the peaceful resolution of the incident using verbal intervention and negotiation.

- Be based on the safest and most reasonable measures to prevent, respond and resolve the situation.

- Be limited to only what is necessary and proportionate to attain the purposes of Corrections and Conditional Release Act .

- Respond to changes in the situation through continuous assessment.

Based on the SMM, there are a number of interventions that are possible such as verbal warnings, dynamic security, conflict resolution and negotiation moving to more invasive techniques such as physical handling, the use of an inflammatory or chemical agent, up to and including the use of batons and restraint equipment. Over the five year period, from 2011-12 to 2015-16 while the in-custody population actually declined by 3.4% the total number of interventions increased by 97% (from 1,600 interventions in 2011-12 to 3,148 in 2015-16). Increases were seen in the use of physical handling and restraint equipment as well as the use of inflammatory spray. The rate of use of inflammatory agent far surpassed that of physical handling or restraint equipment, accounting for the majority (60%) of the increase in the overall number of interventions used during a use of force incident.

Use of Inflammatory Agents

Inflammatory (OC) spray became standard issue for most correctional officers in September 2010 (although it took some time for all officers to be equipped with the duty belt issued pepper spray dispenser). Footnote 16 Prior to 2010, inflammatory sprays were locked up at designated control posts, which required staff to either obtain pre-authorization from the institutional head prior to its use or return to the post to retrieve it. Footnote 17 At the Office's insistence, the display or pointing of an inflammatory agent became a reportable use of force in CSC policy in November 2011. From the third quarter of 2012-13 onward, the use of belt-issued inflammatory spray has steadily risen. In 2012-13, there were 198 interventions using belt-issued inflammatory agent and 237 uses of the Mark IX (control post) spray. By 2015-16, there were over 700 uses of belt-issued spray and 369 uses of the Mark IX. In the first quarter of 2015 alone (April to June), there were more than 200 reported uses of the Mark IV (standard issue) and 123 instances of the use of the Mark IX (control post) the highest recorded usages of these agents in a single quarter.

What is Pepper Spray?

The active ingredient used in inflammatory agents is oleoresin capsicum (OC), an organic agent derived from hot peppers. It is designed to cause a temporary burning sensation and inflammation of mucous membranes and eyes leading to involuntary closure. The Mark III and Mark IV (duty belt) aerosols contain 0.2% active ingredient, whereas the Mark IX (control post) contains 1.3%, a much higher and more potent concentration.