June 28, 2017

The Honourable Ralph Goodale

Minister of Public Safety

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 44 th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigators Message

1. Health Care in Federal Corrections

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

5. Safe and Timely Reintegration

Special Focus on Secure Units at Regional Womens Facilities

Correctional Investigators Outlook for 2017-18

Ed McIssac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Annex A: Summary of Recommendations

Correctional Investigators Message

This is my first Annual Report since being appointed Correctional Investigator in January 2017. Since taking up office, I have made a point to travel to each of the Correctional Service of Canadas (CSC) five regions to meet with staff and visit as many institutions as time away from the Office would allow. Though I previously served as Director of Policy and Senior Counsel then Executive Director and General Counsel for over ten years, my new responsibilities afforded me the opportunity to take a closer and renewed measure of life behind bars in Canada today. What I observed and experienced have enriched and deepened my conversations and engagement with CSC staff and senior level management alike. I have witnessed anew the potential and promise of corrections along with its harsher and bleaker aspects. In my experience, these two sides co-exist wherever and whenever people are deprived of their liberty. As I assume my new duties, I approach the many challenges, demands and expectations of this job as letting more of the light shine through.

Ivan Zinger

Correctional Investigator of Canada

Though I have experienced and learned much in my first few months on the job, there is little doubt that I am still finding my voice as I work my way through the issues that were so adeptly handled by my predecessor, Mr. Howard Sapers. Personally and professionally, the learning curve has been steep, but I have been well-mentored. Appointed several times by different governments, Howard served 12 years as Correctional Investigator from April 2004 to December 2016. His leadership, vision and profile consolidated and advanced the Offices mandate through some difficult issues and some equally challenging times. Howard raised and championed issues of national prominence and concern, such as mental health and corrections, prevention of deaths in custody, safe and humane custody, Indigenous and women offenders. His indelible imprint continues to influence and inspire our work. Indeed, many of the issues and priorities developed in this report were in fact initiated under Howards leadership, though the findings and recommendations are my own.

Transitions are never easy affairs. I am fortunate to be assisted by the same management team, though some have taken on more demanding assignments in more senior roles. I grow more confident in my position each and every day thanks to their invaluable support, advice and guidance. I appreciated the efforts of all staff in maintaining a business as usual approach through a period of considerable and lengthy uncertainty that surrounded the appointment of Howards successor.

Even with changes in senior leadership, the Offices purpose and function remains the same: to serve as an Ombudsman for federally sentenced offenders and to investigate offender complaints, individually and as a group, related to decisions, recommendations, acts or omissions of the Correctional Service. The Offices priorities have not changed, though there may be some nuances in how they are pursued and presented under my direction. The mandate of the Correctional Investigator is to investigate individual offender and systemic issues in federal corrections and make recommendations to ensure safe, lawful and humane custody.

This mandate, I believe, can only be achieved through recognition that corrections is in the human rights business. Every aspect of a prisoners life from whether or when they have visits or calls with family and friends to whether and how they may practice their religion, and even what, when, where or how much they eat and when they rest, sleep, socialize or exercise is highly regulated, subject to the power, control and discretion of correctional authorities. Understandably, lack of control and autonomy over how the most basic necessities of life are met can be a considerable source of frustration and anxiety for prisoners. Security classification, penitentiary placement, use of force, search and seizure, transfer and segregation placements all have significant life and liberty implications for people behind bars. Under such conditions, prisoners require means and access to an independent body to bring forward and resolve legitimate complaints and grievances, in confidence, and without fear of reprisal. If corrections is first and foremost a human rights endeavour, then the protection, promotion and preservation of human dignity and decency behind bars continues to require vigilance.

My first annual report is purposefully illustrated with many visual reminders from my recent visits to institutions across the country. Given every picture tells a story and is worth a thousand words, then this report promises to be briefer and perhaps more visually arresting than in previous years. True to form, at every institution that I visited the promise and predicament of corrections was prominently on display. While I saw some excellent examples of offenders productively engaged in prison industries, I also observed too many other instances where they were either unemployed or underemployed or not participating in any educational, vocational or correctional programming. Time spent in cellular confinement seemed particularly unreasonable in many of the enhanced supervision or structured living units that I visited. The proliferation of these units seems to be an unintended consequence of the effort and priority given to reduce segregation admissions and length of stay. However, as is so often the case in corrections, just as one problem appears solved, another is created.

At Edmonton Institution, I witnessed outdoor segregation yards that were actually cages, easily mistaken for a dog run or kennel. I was told that these so-called yards were built at a time when segregation numbers were double what they are today. Due to incompatibles, rival gangs and population pressures, some segregated inmates were not able to get their required hour of outdoor yard time in association with others. The individual yards were put into service as a population management measure and to (minimally) meet a legal entitlement. Going forward, I can see no redeeming value or purpose in continuing their use. At that same institution, the Office had earlier investigated a series of policy violations, allegations of mistreatment of offenders and potential human rights abuses which seemed to originate from a dysfunctional and toxic workplace. While labour management relations do not fall under the purview of my Office, I am often compelled to investigate when problematic elements of organizational culture generate adverse impacts for those under CSCs care and custody. Rehabilitation and reintegration cannot be accomplished in a workplace that tolerates a culture of indifference or impunity. I am encouraged by CSCs efforts to address the toxic workplace environment at Edmonton Institution, including moving forward on implementing recommendations of an independent report commissioned by the Service. I am hopeful that the work environment of staff and living conditions of prisoners will improve as a result.

Photo of outdoor segregation yard at Edmonton Institution.

On other visits, I walked through many featureless and uninviting outdoor exercise yards predictably and uniformly covered in asphalt or concrete. At a medium security facility in British Columbia I sat scrunched and stooped in the back of a prison transport van, the insert of which is completely outfitted in aluminum and stainless steel hardware. The compartment where shackled prisoners are kept to take them to attend court or medical appointments is totally devoid of any comfort or safety feature, including seatbelts. The experience left me feeling as if personal safety and human dignity did not matter to the designers or operators of such vehicles.

Photo of outdoor "exercise" yard showing concrete walls and metal bars.

Photo of metal door of inmate transport van.

I observed segregation and isolation units and even cells on regular living areas that had no source of natural light or manual ventilation. Stainless steel toilets and sinks bolted to the floor and other permanently fixed furnishings dominate cellular interiors at most penitentiaries, creating an unnecessarily stark and foreboding environment for human habitation. At one institution, the door to the segregation cell was inexplicably covered over in plastic safety glass. When I asked why, staff could not form a cogent defense or reason that did not default to some undefined but ubiquitous security concern of one kind or another. As is so often seen in corrections, the extraordinary case becomes the response upon which all other future actions are mediated. Once implemented it is rare for a temporary security measure to be removed or lowered: it simply becomes the new standard.

Segregation cell covered over in plastic safety glass

I also made a point to visit Saskatchewan Penitentiary in Prince Albert where a full-scale riot in December 2016 in the medium security sector left one inmate murdered, another seriously assaulted and several others requiring hospitalization for shotgun wounds. The ensuing rampage and destruction of government property rendered many of the living units uninhabitable. In search of some other plausible explanation for the incomprehensible violence and mayhem beyond bad or inadequate food, I noted that some of the cells in that forbidding and antiquated facility housed two inmates even though there is barely adequate space for one. Standing in the middle of another cell, I could reach out and touch the sides of both walls. Long after the rage of the riot had been quelled, a palpable sense of tension lingers in that facility. I could not help but notice that the overwhelming majority of its occupants are young, desperate Indigenous men. To my mind, the year-on-year increase in the over-representation of Indigenous people in Canadian jails and prisons is among this countrys most pressing social justice and human rights issues.

"Uninhabitable" living unit after riot

Standing in the middle of the cell I could reach out and touch both sides of both walls.

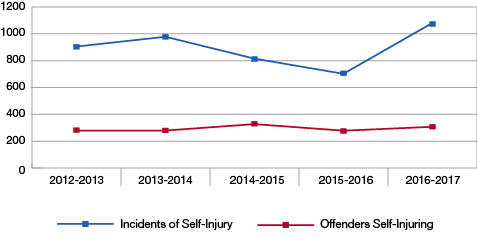

One can imagine the sense of futility and despair such environments and conditions of confinement elicit from people who are often mentally unwell, or whose lives have been touched or marked by some combination of alcohol or drug addiction, family dysfunction, discrimination, poverty, childhood violence, abuse or trauma. Elevated rates of prison self-injury and suicide, high prevalence of mental illness and premature natural mortality behind bars speak to the unremittingly high costs of imprisonment for some of Canadas more vulnerable populations.

Beyond these initial observations and reactions, one of my first orders of business is to find a way to reduce the volume of contacts and complaints brought forward to my Office involving relatively minor matters. While I understand and appreciate that small things mean a lot to prisoners, the capacity of the Correctional Service to respond to everyday inmate requests in a timely and appropriate manner is a source of constant but unnecessary frustration for inmates and an increasingly serious point of contention with my Office. Even relatively routine requests affecting living conditions and institutional routines e.g. access to canteen, mail delivery problems, issues related to lost, damaged or confiscated personal effects, meal times, inmate movement, out-of-cell time often extend well beyond the 15-day period which the correctional authority grants itself to respond, or they simply go unanswered altogether. In some facilities, there appears to be no standard process for tracking or monitoring comparatively simple requests from inmates.

To the point of the matter, too much of my investigators time during regular institutional visits is taken up intervening or resolving issues or complaints that should have been addressed through internal systems. Straightforward issues are most properly dealt with at source, not routinely escalated to my Office. Even as my Office takes steps to address founded complaints through better triage at intake and early resolution, there appears to be no end to the issues that quite properly belong with or have been created by CSC maladministration. Common examples include: tracking down an inmate request that has not been answered or dealt with appropriately; inquiring about an unreasonably delayed response to an inmate complaint filed at the institutional level; following-up on an overdue security or pay level review; issuing reminders about pending applications for a family visit, work release or temporary absence. All of these seem an unnecessary and redundant burden on staff time and resources. Effort invested to resolve these and other matters impacts on the Offices ability to address more systemic or emergency matters, such as transfers, access to medical care or segregation. I believe that, with some changes to policy and practice within CSC and my Office, service improvements can be made to the mutual benefit of all parties.

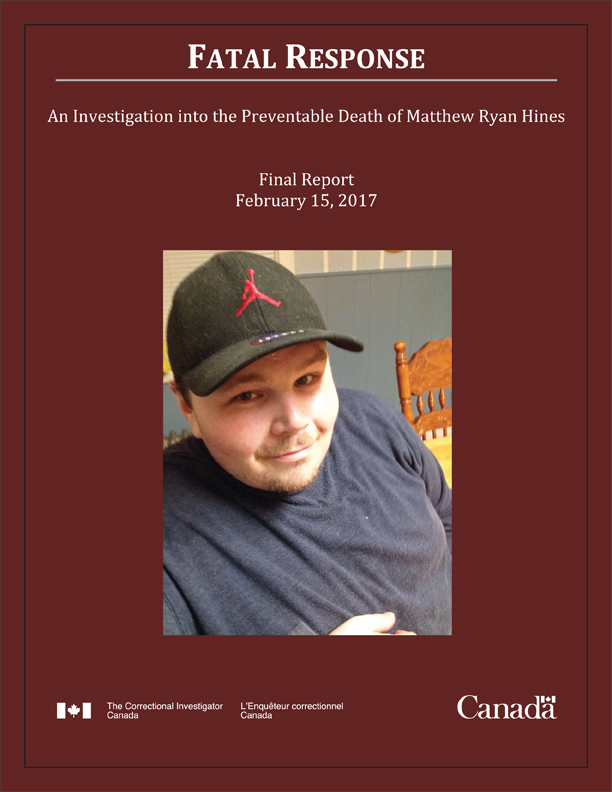

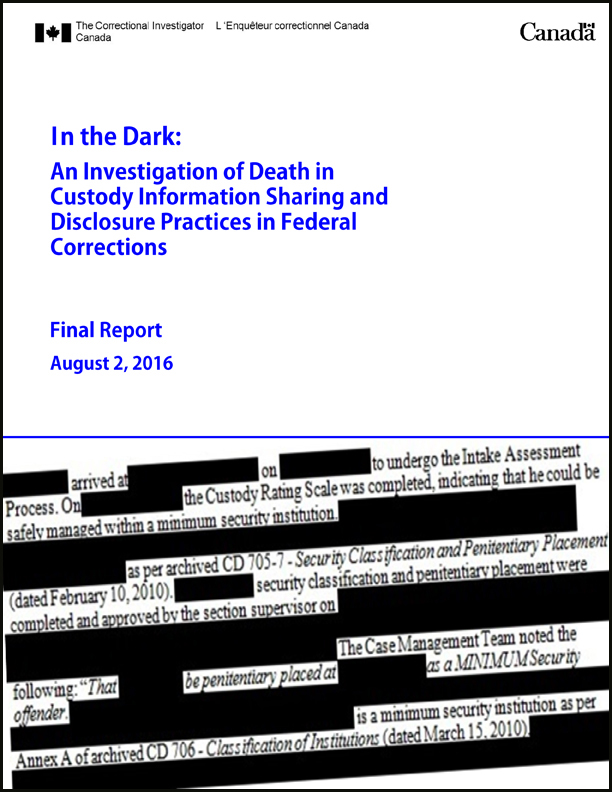

I will conclude by drawing attention to some of the major investigations and systemic reviews completed during the reporting period. The Office conducted two major investigations. In the Dark: An Investigation of Death in Custody Information Sharing and Disclosure Practices in Federal Corrections was released as a public interest report on August 2, 2016, and Fatal Response: An Investigation into the Preventable Death of Matthew Ryan Hines was tabled as a Special Report to Parliament on May 2, 2017. An investigation into the experience of young adult offenders in federal custody (age 18 to 21) was initiated mid-year and is ongoing. A comprehensive review of the Secure Units (Maximum Security) at the Regional Womens facilities was also completed, the findings of which are incorporated in this report.

Other major thematic, policy and priority reviews initiated or monitored through the reporting period included the following:

- Timely and appropriate recognition and response to medical emergencies and/or psychological distress.

- Alternatives to incarceration for seriously mentally ill offenders (complex needs).

- Conditions of confinement in administrative segregation.

- Controls and safeguards on the use of chemical and inflammatory sprays in use of force interventions.

- Adequacy and appropriateness of the CSC investigating and disciplining itself.

- Embedding gender identity and gender expression in federal correctional practice and policy.

- Implications of Medical Assistance in Dying legislation for federal corrections.

- Components of an integrated and comprehensive national older/aging offender strategy (age 50 and older).

This report serves as a summary of the collective output of a small but extraordinarily talented and dedicated team of professionals. As the newly appointed Correctional Investigator, I am proud to lead and represent their work in my first Annual Report to Parliament.

Ivan Zinger, J.D.,

.D.

Correctional Investigator

June 2017

1. Health Care in Federal Corrections

Photo of health care room at a federal penitentiary.

Issues in Focus

United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules)

The provision of health care for prisoners is a State responsibility. Prisoners should enjoy the same standards of health care that are available in the community. (Rule 24)

All prisons shall ensure prompt access to medical attention in urgent cases. Prisoners who require specialized treatment or surgery shall be transferred to specialized institutions or to civil hospitals. (Rule 27 (1))

Clinical decisions may only be taken by the responsible health-care professionals and may not be overruled or ignored by non-medical prison staff. (Rule 27 (2))

The relationship between the physician or other health-care professionals and the prisoners shall be governed by the same ethical and professional standards as those applicable to patients in the community. (Rule 32 (1))

Health-care personnel shall not have any role in the imposition of disciplinary sanctions or other restrictive measures. (Rule 46)

The Mandela Rules Footnote 1 and the Role of Health Care Services and Health Care Providers

The role of medical staff in prison, as in the community, is to protect, promote and provide for the care of their patients, who also happen to be prisoners. The same ethical and professional standards of health care practice informed consent, patient autonomy, confidentiality apply in prison as in the community. I n carrying out their duties, the Mandela Rules instruct that correctional health care workers must be provided full clinical and professional independence. Clinical decisions may only be taken by health care professionals; the prison administration must not influence, interfere with or go against the decisions of the health care team. Health care staff must never be involved in assessing fitness for, approving or inflicting disciplinary punishments. Footnote 2

As concerning as the unauthorized and illegal body cavity search case is it is not the only example where dual loyalties can create ethical dilemmas and role conflicts for correctional health care providers. CSC segregation policy, for example, requires health care professionals to conduct mental health assessments of inmates and to be part of the review body that determines whether or not a prisoner should remain in administrative segregation (solitary confinement). Under the newly revised Mandela Rules , not only should health care staff not be involved in imposition of disciplinary sanctions or other restrictive measures, they have an additional positive obligation to report to the director, without delay, any adverse effect of disciplinary sanctions or other restrictive measures on the physical or mental health of a prisoner subjected to such sanctions or measures and shall advise the director if they consider it necessary to terminate or alter them for physical or mental health reasons (Rule 46 (2)).

Issues in Focus

Unauthorized and Illegal Body Cavity Search

- A body cavity search is an extremely invasive procedure that requires, by law, the highest degree of compliance with procedural safeguards.

- The Office received a complaint from an inmate that a body cavity search had been performed on him during a lockdown and search for a handgun that was suspected to have been brought into the institution. Suspicion initially and throughout the lockdown period focused primarily on this one inmate.

- He was strip searched five times over an 8-day period. Since the suspected weapon could not be located during the search, the Warden authorized an x-ray search of the inmate. Three x-rays were taken and all were clean.

- Following the x-ray searches, the institutional doctor asked the inmate to perform a body cavity search, purportedly to ensure he was not concealing anything. Although the inmate verbally consented to the procedure (reluctantly as he clearly felt intimidated and coerced to comply), the search itself was conducted in violation of several sections of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act . Specifically:

- The Warden had not authorized the body cavity search.

- The offenders written consent was not obtained.

- He was not offered the opportunity to contact legal counsel.

- In this case, the body cavity search was performed entirely for security and not medical reasons. It did not seem to be absolutely necessary given that the x-ray exams had already revealed nothing was being concealed. There were no reasonable grounds to believe that a handgun was concealed after the x-rays were taken a legal requirement to authorize a body cavity search.

- CSC agreed with the Offices recommendation to refer the case for review to the appropriate provincial regulatory body, and, also at the insistence of the Office, a CSC National Board of Investigation was convened.

Moreover, the Rules direct that the imposition of solitary confinement should be prohibited in the case of prisoners with mental or physical disabilities when their conditions would be exacerbated by such measures (Rule 45 (2)). The Rules recognize that forging or maintaining therapeutic relationships is difficult, if not impossible, when clinicians are asked to be part of potentially harmful correctional practice. Finally, though both policy and legislation still allow for indefinite or prolonged confinement in segregation, such practices are prohibited under the revised Mandela Rules.

Management of Inmate Self-Injurious and Suicidal Behaviour

The management of self-injurious and/or suicidal persons in federal custody has long been a concern of this Office. Footnote 3 Despite extensive Office commentary, findings and recommendations going back several years, there remain significant omissions in the use of physical restraints to manage self-injurious and suicidal behaviour in prison. Though the Mandela Rules recognize certain legitimate reasons for using physical restraints in correctional settings, including preventing prisoners from injuring or harming themselves (Rule 47 2(b)), their use is permitted only in narrow and exceptional circumstances in line with principles of legality, necessity and proportionality, and when all other options have been exhausted. For corrections, these principles translate as:

- Physical restraints should only be used if an offender presents an immediate and extreme risk of injury to him/herself or to others.

- Physical restraints should be applied as a last resort and for the shortest period necessary consistent with the preservation of life and least restrictive option.

- Physical restraints should not be used as punishment or retaliation.

- Human dignity should be maintained at all times that an offender is subject to restraint equipment.

Self-Injurious Incidents and Number of Offenders

Photo of a Pinel restraint bed.

As defined in CSC health care policy, the Pinel Restraint System (PRS) is a variable-point medical restraint system. Footnote 4 It is the only restraint system authorized to be used for self-injurious behaviour in maximum and medium security institutions, women offender institutions and Regional Treatment Centres. Footnote 5 As a medical device, Footnote 6 it would seem appropriate that its use should be authorized by professional health care staff working in a hospital setting (i.e. Regional Treatment Centres, which are designated Psychiatric Hospitals). To ensure the PRS is used exceptionally, sparingly and only by authorization of a psychiatrist and under the direct supervision of mental health professionals, this device should be available only in designated Treatment Centers. If an inmate in a regular institution cannot be controlled, a psychiatrist or physician can administer emergency medical treatment until such time as a transfer to an outside hospital or Treatment Centre can be initiated. Interventions to preserve life and prevent serious bodily injury may occur in mainstream institutions, but these involve an emergency response to stop an inmate from engaging in further self-injurious behaviour, regardless of whether there was intent to end life. By continuing to make this device available across all security levels rather than limiting its use to CSCs Regional Treatment Centres, the policy effectively normalizes its use in mainstream institutions. It is not consistent with a least restraint principle, a direction that recognizes the potentially harmful effects of using physical or environmental restraint (e.g. seclusion) to manage people in acute psychological distress.

Under current policy, the decision to authorize the application, reduction of use or removal of instruments of restraint to prevent self-injury continues to reside with the Warden, not health care providers. Footnote 7 With respect, this decision properly resides with clinicians. The Office has further recommended that all instances where restraints are applied to prevent self-injury should be considered a reportable use of force. In a correctional setting, the so-called consensual or cooperative use of physical restraints to prevent self-injury does not reflect standards of valid, voluntary and informed consent. Informed consent is a legal/ethical requirement. Further, for accountability purposes, video monitoring of the entire duration of placement in the PRS, including removal of restraints, should be required policy and operational practice.

Health Services - Pinel Restraint Room (medium security)

It is instructive that the policy prescribes that inmates on high suicide/self-injury watch are to be placed in an observation cell that minimally provides the basic necessities to preserve and dignify human life:

a. at minimum, a security gown, at all times

b. a security blanket and mattress, unless the inmate attempts to use these items in a manner that is self-injurious or affects staffs ability to monitor the inmate. In this case, the items can be removed from the cell, with the intention of returning the items as soon as safely practicable

c. the offer of a change of security gown/blanket daily, or as required

d. fluids and food that can be easily consumed without cutlery or tableware (finger foods)

e. hygiene items (the health care professional will determine when to provide hygiene items if these items are associated with any risk for suicidal or self-injurious behaviour and will inform the Duty Correctional Manager).

There seems little recognition that confinement in these conditions may actually promote or deepen psychological distress or lead to further or even more lethal acts of self-harm or attempts to end life. The fact that these stark environments are often viewed as punitive or even damaging for people experiencing significant psychological distress is not acknowledged. There is no requirement for security staff who are assigned constant, direct observation of self-injurious or suicidal inmates to also be a source of human contact, comfort or compassion. Moreover, the policy now allows for an inmate to be kept in these conditions up to 15 days before Regional authorities are informed or engaged in monitoring the case. As with administrative segregation, there is no limit or cap on how long an inmate can actually be kept in a state of clinical seclusion or isolation. This situation, which continues to allow for distressed individuals to be kept in potentially unsafe and harmful conditions of detention indefinitely, speaks to the contradictions between the security and control orientation of this policy direction at the expense of any defensible therapeutic aims.

- I recommend that CSC review, in FY 2017-18, its health care policies, practices and authorities to ensure they are compliant with the revised United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules), specifically those relating to health care services (Rules 24 to 35), solitary confinement (Rules 45 and 46) and instruments of restraint (Rules 47 to 49).

Alternatives to Incarceration

The Office continues to call for external psychiatric hospital placements in cases of extremely complex or significant mental illness. These cases continue to arise in mainstream institutions that lack the appropriate capacity, resources and infrastructure to manage serious mental health conditions. The issue is especially problematic in womens corrections as there is no dedicated, stand-alone treatment facility for women in federal corrections. Footnote 8 In the Pacific Region, women in need of emergency health care or hospitalization are temporarily transferred to and housed in a unit at the all-male regional psychiatric facility. Isolated from the other male patients, these mentally ill women are managed in segregation-like conditions not conducive to treatment. This practice systematically discriminates against women struggling with mental health problems; it is totally unacceptable and contrary to international human rights standards, including the Mandela Rules.

- I recommend that transferring mentally ill women in the Pacific Region to the all-male Regional Treatment Centre be absolutely and explicitly prohibited. Women requiring mental health treatment should be transferred to the female unit at the Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC) in Saskatoon, or, preferably, to a local external community psychiatric hospital as required.

Mental Health Care Funding for Alternatives to Penitentiary

There continues to be inadequate treatment space for significantly mentally ill persons who cannot be safely or humanely managed in a federal correctional facility. This need remains especially acute for federally sentenced women. The CSC needs to create, conclude and fund alternative service agreements and arrangements with provincial and territorial mental health providers that would allow for the transfer and placement of complex needs offenders in community psychiatric facilities. Footnote 9 In recent years, there has been only one agreement concluded: it provides for two beds at the Brockville Mental Health Centre in Ontario. This situation is simply inadequate and unacceptable.

Photo of health care room with medical bed.

My frustration here stems from the fact that CSC could have funded and already created community capacity that would provide the level of care necessary to manage challenging or complex mental health cases. The Ashley Smith inquest, concluded in December 2013, made very specific recommendations to realize such an outcome:

- That female inmates with serious mental health issues and/or self-injurious behaviours serve their federal terms of imprisonment in a federally-operated treatment facility, not a security-focused, prison-like environment.

- That such a facility or facilities be made available at least on a regional basis, and particularly in Ontario.

- That CSC negotiate arrangements with provincial health care facilities to provide long-term treatment to female inmates who chronically engage in self-injurious behavior or display other serious mental health problems. Further:

a) that the Government of Canada sufficiently and sustainably funds the CSC to enter into such agreements;

b)that this will include any and all capital and operating costs associated with the establishment of such facilities, and that the accommodation and treatment of female inmates therein will be the responsibility of CSC.

To come to the point of the matter, even with the recent expansion of intermediate mental health care beds at the regional womens facilities (for a total of 60 beds across the country) there still seems to be better treatment capacity for men in federal corrections. The CSC claims that it is too costly to place and treat significantly mentally ill women in provincial psychiatric facilities, and, further, these facilities are reluctant to accept complex needs cases requiring an acute level of care and/or supervision. These claims do not seem entirely substantiated given that this Office is aware that CSC has received proposals from external psychiatric/forensics facilities that would expand treatment capacity in the community contingent on the Service agreeing to fund the arrangements appropriately based on a higher professional staff to patient ratio (or higher per diem rate). The failure to conclude more federal/provincial exchange of service agreements for community placements based on funding considerations seems particularly problematic and short-sighted, especially if the full range of costs associated with managing acute needs in prison versus forensic settings is considered (e.g. use of force interventions, segregation placements, 24/7 direct observation, etc). Moreover, the risk of managing serial self-injurious and/or suicidal women on an ad-hoc and exceptional basis needs to be balanced against therapeutic not purely funding considerations. The price of not doing so may ultimately be more tragic and preventable deaths in custody and costly civil settlements in wrongful death cases.

- I recommend that CSC issue a Request for Proposal to fund or expand community bed treatment capacity to accommodate up to 12 federally sentenced women requiring an intensive level of mental health intervention, care and supervision.

Gender Identity and Gender Expression Rights in Corrections

In last years Annual Report, the Office recommended that upon request and subject to case-by-case consideration of treatment needs, safety and privacy, transgender or intersex inmates should not be presumptively refused placement in an institution of the gender they identify with. In response, the Service indicated that in fiscal year 2016-17, CSC will initiate a review of its policies to ensure the rights of transgender inmates are protected, including consideration of safety, security and privacy related to placement. This review will be undertaken while CSC closely monitors the progression of proposed legislative changes through Parliament ...

The review and promulgation of CSCs new gender dysphoria policy on January 9, 2017 did not, as it turned out, permit penitentiary placement of transgender prisoners based on gender identity. In fact, just a few days after CSC had promulgated its revised policy direction, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau responding to a question at a town hall gathering, promised that federally sentenced offenders could indeed serve their prison sentences based on their gender identity. A major policy reversal immediately followed the Prime Ministers intervention, with the Minister of Public Safety and CSC announcing that the Service would indeed allow for penitentiary placement of transgender persons based on gender, not genitalia.

Issues in Focus

The Experience of Being Transgender in Federal Custody

- Until recently, a transgender inmate spent most of their sentence (over 10 years) in a facility representing their assigned sex at birth.

- The experience and impact, both physical and emotional, of the lack of recognition of gender identity and gender expression seems beyond comprehension. The inmate documented numerous incidents where they were subjected to crude and offensive comments from CSC staff and inmates, pushed to the side by healthcare staff, refused hormone therapy treatment, refused private showers and denied recognition of a name change.

- Desperation led the inmate to attempt suicide, self-mutilate genitalia and take pills bought from other inmates. The inmate fell into depression as a result of the treatment and lack of movement on the part of CSC with respect to the inmates sex change.

- The offender filed a complaint to the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) which vividly detailed the experience and treatment of being transgender in a federal correctional institution.

- The inmate died from complications not long after being transferred to an institution representing their gender identity. Though the death is still under investigation and appears unrelated to the inmates gender identity, the family has decided to pursue the human rights complaint on the inmates behalf.

At various points over the reporting period, CSCs approach to this issue has been contradictory, disappointing and frustrating. Following the policy reversal, CSC initiated a major effort to bring the rest of CSCs policy framework admission, classification, searches, use of force, personal property, health services, etc. into line with Bill C-16, which would amend the Canadian Human Rights Act to add gender identity and gender expression to the list of prohibited grounds of discrimination. This bill is expected to become law.

In the context of federal correctional policy and practice, there does not appear to be a very deep understanding or appreciation for what the terms gender identity and gender expression actually mean. Other jurisdictions in Canada, notably British Columbia and Ontario, have for some time now been responsive and inclusive in their approach to ensuring that the rights of transgender, transsexual and other gender non-conforming peoples are respected and protected in custody; in contrast, federal corrections appears mired, if not stuck, in conventional attitudes and assumptions. Legislative change is coming, and CSC needs to embrace it. Unresponsive policy and practice can lead to unimaginable and needless suffering. This must change.

Ontario Correctional Services Policy for the Admission, Classification and Placement of Trans Inmates

Highlights

- Policy recognizes a persons self-identified gender, preferred name and pronouns, as well as their housing preference, unless it can be proven that there are overriding health or safety concerns which cannot be resolved.

- Trans inmates must be given the opportunity to choose who will perform any searches. The inmate is offered privacy in which to be searched, including any searches of prosthetics.

- Information about an inmates gender identity or history will only be shared with those directly involved with their care, and only when relevant.

- Trans inmates are to be integrated into general population, not isolated or segregated.

- Trans inmates must be provided with their preferred institutional clothing and underclothing.

- Trans inmates must be offered individual and private access to the shower and toilet for safety and privacy purposes.

- The policy is supported by a comprehensive staff training and awareness program.

Source: Ontario Correctional Services, January 2015

Harm Reduction Measures in Prison (Safe Tattooing)

Increasingly popular in the larger Canadian society, tattooing is still a prohibited practice in federal institutions. People who engage in tattooing behind bars are forced to conduct their work underground, often sharing and reusing unsterile homemade tattooing equipment. Illicit prison tattooing has been associated with higher rates of blood-borne infections such as Hepatitis C and HIV among the inmate population. Footnote 10 And when there is no safe means of disposal of used needles, the health risks extend beyond inmates, impacting on corrections staff. Between April 1, 2011 and April 1, 2017, there were sixteen incidents where a staff member was accidentally poked by a needle/syringe, primarily as a result of a search. Footnote 11 The Canadian public is also at risk as offenders returning to communities bring with them any infections or health care issues acquired during incarceration.

In 2005, CSC began a pilot program targeted at controlling the spread of infectious disease with the implementation of tattoo rooms in six federal institutions (one mens institution in each of the five regions and one womens institution). Despite an evaluation conducted by CSC indicating that the program had the potential to reduce harm, decrease exposure to health risk and enhance the health and safety of staff members, inmates and the general public, the program was terminated in 2007 by the Conservative government. Also, as CSCs own evaluation demonstrated, the program provided important employment opportunities for inmates while incarcerated and more importantly, marketable skills upon release into the community. While CSC continues to offer bleach as a means of cleaning needles, this measure has been found to have limited effectiveness in preventing the spread of Hepatitis C. Footnote 12 Re-instating the safe tattooing program within federal institutions would not only minimize the risk of transmission of infectious diseases, but it could also save money over the long-term, particularly given the high costs associated with treating HIV and Hepatitis C in prison.

- I recommend that CSC reintroduce safe tattooing as a national program.

Medical Assistance in Dying

Bill C-14, medical assistance in dying (or MAID), became law in Canada on June 17, 2016. In addition to making assisted death available to federally sentenced offenders, the legislation also amends the Corrections and Conditional Release Act to exempt CSC from having to conduct a mortality investigation when an offender receives medical assistance in dying. In the reporting period, the Office received and commented on proposed guidelines for MAID in federal corrections. Though the guidelines have not yet been promulgated, central questions come down to where, when and how best to deliver end of life care to a terminally ill person who is still under correctional supervision. They can be summarized as:

- The decision to seek medical assistance in dying should be made, to the extent possible, while the palliated individual is in the community, preferably on parole by exception status.

- Consideration of the pressures, restrictions and influences that limit an inmate- patients option(s) who is terminally ill to end life at a place and time of their own preference and choice.

- Need for a Patient Advocate to protect inmate patients rights and ensure they fully understand and meet the eligibility criteria of MAID.

Photo of health care room with medical bed and devices.

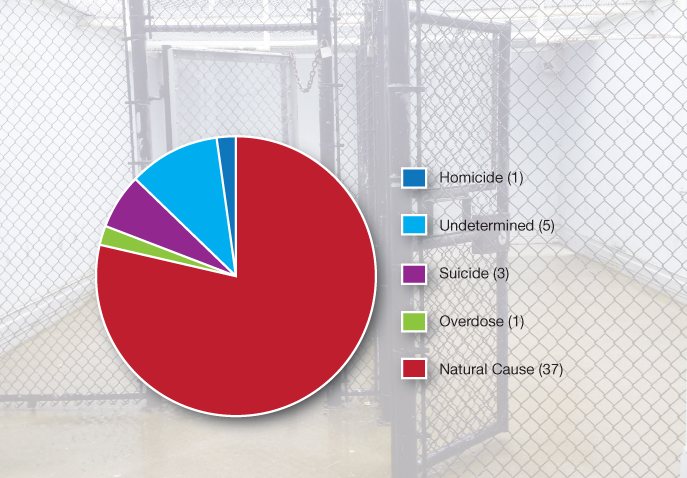

Managing palliation in end of life situations within a prison setting is challenging and costly. Unfortunately, it is also an increasingly frequent necessity: in 2016-17, there were 37 deaths in federal custody by natural cause. Although the data on where the offenders died (penitentiary, treatment center or external community hospital), and whether palliative or end of life care was provided are not currently available. Experience indicates that most natural deaths will have been expected and occurred in a federal penitentiary.

In the Offices view, the manner, place and timing of MAID needs to provide as much practical choice as possible in how palliative inmates might otherwise choose to end their life. They should not simply be referred to a community hospital for the procedure. CSC must work with the Parole Board to ensure that palliative or terminally ill inmates seek Section 121 parole by exception as early as possible to allow them to spend as much time in the community among family and friends as possible. Once in the community, offenders can decide to seek MAID. Consistent with the legislation, compassionate and humanitarian considerations family and community supports, time spent in the community before the procedure, as well as some choice over the manner and place where MAID is provided should be reflected in the guidelines. Such considerations are more in keeping with the spirit in which medical assistance in dying is made available to the rest of Canadians. Only in rare and exceptional circumstances (e.g. where they actually continue to pose an undue risk to society) should palliative or terminally ill inmates remain in custody to die.

As the Office has previously documented, the criteria for granting compassionate release to a terminally ill offender are extremely restrictive. The documentation required by the Parole Board includes medical evidence/rationale that end of life is not only imminent, but also certain; in some cases, the Board has required medical doctors to provide a defined period of life expectancy. Such criteria do not reflect the spirit or intent in which MAID was enacted. Indeed, the legislated criteria (grievous and irremediable medical condition where natural death has become reasonably foreseeable) conflicts with current Parole Board practice. Compassionate release decision-making must better reflect and align with the legislated criteria of medical assistance in dying.

For its part, CSC needs to more quickly and proactively prepare and process eligible cases so that MAID does not become the default mechanism for an exceptional release option that too often fails to deliver on compassionate or humanitarian grounds. Terminally ill inmates should not have to die in prison simply because their case was not processed or brought before the Parole Board in a sufficiently complete or timely manner. The Guidelines should specifically reference section 121 of the CCRA to make it clear that parole by exception may be granted to any offender who is palliative or terminally ill at any time during their sentence and does not pose an undue risk to society.

Finally, the Office strongly recommends implementation of a separate, dedicated Patient Advocate system for federal corrections. Given the pressures and concerns noted above, there needs to be independent assurance and an external oversight mechanism to ensure that the inmate patient freely and voluntarily consents to medical assistance in dying. Footnote 13 A Patient Advocate system could also counsel and advise CSC on ethical and practical issues around how best to compassionately and humanely provide end of life care to a person who is still under sentence in a community setting.

- I recommend that compassionate and humanitarian interests guide policy and practice in implementing Medical Assistance in Dying legislation in federal corrections. The decision of a palliative or terminally ill offender to end life through MAID should be freely and voluntarily made in the community.

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

47 deaths occured in federal custody in 2016-2017.

Fatal Response

Photo of cover page of Special Report Fatal Response: An Investigation into

the Preventable Death of Matthew Ryan Hines. Final Report, February 15, 2017.

Matthew Ryan Hines was only 33 years old when he died unexpectedly in federal custody following a series of use of force incidents at Dorchester Penitentiary on May 26, 2017. He was serving a five-year federal sentence for robbery and property related offences. Matthew had a history of substance use and mental health issues. On the night in question, responding staff initially thought Matthew was under the influence of an illicit substance. Toxicology reports confirm that Matthews death was not due to an overdose.

I submitted my Final Report of this investigation to the Minister of Public Safety on February 15, 2017. At that time, I requested that it be tabled in Parliament as a Special Report under provisions of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act . This is only the third time in the history of my Office that this provision has been used. In my opinion, Matthews tragic and preventable death is a matter of such urgency and public importance that it could not wait or be deferred. As the Minister of Public Safety had stated in August 2016, Canadians deserve to know how and why Matthew died in federal custody. Fatal Response was tabled in Parliament on May 2, 2017.

My investigation concludes that Matthews death was preventable. The repeated use of pepper spray at very close range seems to have contributed to the medical emergency which ultimately led to Matthews death from acute asphyxia. Matthew appears to have literally choked to death. Staff failed to recognize and respond to his medical distress. My report details a catastrophic and fatal breakdown in the chain of response and accountability. No single responding officer stepped forward to assume leadership and command of an incident that escalated from a routine use of force intervention to a life-threatening event in a matter of minutes.

Key findings of the investigation focus on issues of transparency and accountability in federal corrections. These include:

- Inadequate controls on the use of inflammatory agents (pepper spray) in corrections.

- Security-driven interventions to underlying mental health behaviours.

- Poor communication and inadequate information-sharing among security and clinical staff.

- Failure to recognize and respond to a medical emergency.

- Adequacy and appropriateness of CSC staff investigating and disciplining itself.

- Lack of timely and transparent sharing of information with the family of the deceased.

Despite these and other violations of law and policy, no senior manager has ever been retroactively disciplined or held to account for the staff errors and omissions that contributed to Matthews death.

Fatal Response makes ten recommendations, several of which are directed to addressing gaps in how correctional staff recognize and respond to situations of medical emergency or mental health distress. The Correctional Service acknowledged the areas of concern identified in the report and accepted all ten recommendations. Significantly, the response contains an apology to the Hines family from CSCs Commissioner for inaccurate information that was shared with them following Matthews death. While it is clear that much work remains in preventing deaths in custody, I am encouraged that the Service is committed to learning and making improvements based on the reports findings and recommendations.

Issues in Focus

Fatal Response:

An Investigation into the Preventable Death of Matthew Ryan Hines

Chronology of Events

- The sequence of events leading from use of force to medical emergency and ending in death unfolds remarkably quickly.

- There are two physical altercations with staff, one on Matthews cell range and another in the kitchen area of his living unit. The first use of pepper spray occurs in the kitchen as Matthew is physically restrained by five officers; he is in a prone position with his face down on the floor and handcuffed to the rear.

- From his living unit, Matthew is escorted to segregation where the decontamination shower is located. He is forced to walk backwards with his hands cuffed behind his back. Without warning and under escort of several officers, pepper spray is administered numerous times to Matthews face.

- Matthew suffers the first of several seizures or convulsions in the decontamination shower barely 15 minutes after the initial physical altercation with staff. He never appears to regain consciousness from that point forward. He is dragged by his feet from the segregation shower and taken, by stretcher, to the Penitentiarys treatment room.

- On arrival in the treatment room, Matthew is unconscious, unresponsive and barely breathing. The attending nurse fails to initiate emergency life-saving measures. Matthew is moved into an ambulance, with his hands still cuffed. Less than 50 minutes have elapsed since the initial use of force.

- Emergency life-saving measures are initiated en route to the hospital, but Matthew is declared deceased at Moncton General Hospital shortly after midnight, less than two hours after his brief but fatal encounter with staff.

In the Dark

On August 2, 2016, the Office released In the Dark: An Investigation of Death in Custody Information Sharing and Disclosure Practices in Federal Corrections. The report documents the frustration of families when information is not fully and openly shared following a death of a loved one in custody. The investigation found that even straight- forward factual summaries of the events and circumstances leading to the death were typically not provided. The delays, obstacles and barriers that families encountered in trying to access information about how their family member died in federal custody deny them closure as they grieve their loss. The report concludes that the lack of forthcoming information, numerous delays (investigative reports can be delayed for years), the inappropriate behaviour of some CSC staff and the general feeling that CSC is trying to hide something serve only to compound the grief and hurt of many families.

Photo of cover page of OCI report In the Dark: An Investigation of Death in Custody Information Sharing

and Disclosure Practices in Federal Corrections. Final Report, August 2, 2016

The Service has taken a number of important steps to address issues of concern identified in the report. A facilitated disclosure process and regional point of contact for families have been established, which will help ensure families receive timely and relevant information from the point of notification of the death through to the completion of the investigative process. CSC has modified its approach to vetting and releasing information contained in National Board of Investigation (NBOI) reports where a dedicated team works closely with family members and other partners to ensure that information is shared appropriately and consistently. Positively, the Office has noted that NBOI reports that have been released to family members following this revised approach have contained significantly less redactions and provided families with more information. However, careful monitoring of the implementation of these new procedures is necessary. Footnote 14

Other changes the Service has put in place following the release of this report include: immediately sending a letter of condolence to designated next of kin; training for staff involved in communicating with families and; developing a guide for families explaining CSC policy, responsibilities and the investigative process following a death in custody. I am encouraged by the positive response to the reports findings and recommendations. My Office will continue to monitor their implementation.

Issues in Focus

In the Dark:

An Investigation of Death in Custody Information Sharing and Disclosure Practices in Federal Corrections

What We Investigated

- The Office conducted confidential interviews with eight families whose family member died in federal custody or sustained serious bodily injury over the last three years.

- A comparison of redacted (blacked out) National Board of Investigation (NBOI) reports* released by CSC to families through the Access to Information Act versus the original (un-redacted) report was conducted to assess whether CSC consistently and respectfully exercised appropriate discretion in providing families with information.

What We Found

- CSC does not proactively share information with designated next of kin. Information that may eventually be shared is only done so retroactively once a formal access to information request has been submitted by the next of kin

- Documents provided to families by CSC are often heavily and unnecessarily redacted making it difficult for families to piece together what actually happened.

- No one single point of contact is responsible for ensuring that families are informed.

What We Recommend

The report makes nine recommendations, among them:

- The Service should proactively disclose factually relevant information to families of deceased inmates immediately following a death in custody.

- CSC should develop and implement a facilitated disclosure process.

- CSC should establish a family liaison in each of the five regions.

* Pursuant to section 19 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, when an inmate dies or suffers serious bodily injury, CSC shall forthwith investigate the matter and report to the Commissioner of Corrections.

Response to Medical Emergencies

In addition to the Matthew Hines case, the Office reviewed a number of other incidents where correctional staff failed to recognize or respond to a medical emergency in a timely and appropriate manner. In relation to the case involving a delayed response to a medical emergency (Case 1), it was my Office that initially brought this case forward to the attention of CSCs National Headquarters, not Regional or institutional authorities. My use of force review team flagged the incident after receiving the use of force package. CSC did not initially identify or code this incident as a case involving serious bodily injury (despite the fact that the victim spent several days in outside hospital), a trigger which warrants and prompts a Board of Investigation process. In Case 2 use of force intervention turned medical emergency there was a failure to recognize medical distress and react accordingly. It is difficult to learn from these events when the post-incident reviews fail to bring forward, much less correct, compliance and accountability issues.

Both cases highlight the importance of responding staff continuously assessing and reassessing events and situations as they evolve. Both scenarios point to serious deficiencies in an intervention model that relies on or prioritizes isolation, control and containment strategies and responses. Such a model may be appropriate for security-based use of force scenarios, but it is inadequate for managing a medical emergency. In a prison setting, a life-threatening event can develop quickly and unexpectedly where the difference between life and death is measured literally in seconds. Finally, both cases underscore the need for round-the-clock health care coverage at all medium, maximum and multi-level federal institutions. The lack of weekend and after-hours on-site medical staff at most penitentiaries is a significant gap in CSCs death in custody prevention efforts.

Conclusion

The lessons to be drawn from the preventable death of Matthew Hines and other near misses could not be any clearer. The circumstances and events that give rise to avertable deaths in custody are not isolated. The omissions, deficiencies and issues of concern identified in Fatal Response are systemic and pervasive in nature; they have all been raised before in the context of previous death in custody investigations. Some still resonate back in time to the preventable death of Ashley Smith (October 2007), including the need for a separate and distinct intervention model to manage medical emergencies. Unfortunately, there are many more Matthews and Ashleys in the federal correctional system. From a prevention standpoint, applying a security-driven intervention model to medical or psychological distress is an inherently risky approach to managing a population that overwhelmingly presents with substance use or dependence, mental health and behavioural issues. The key going forward is to promote and enhance training, skills and techniques that will alert responding staff to events, situations or behaviours before they become life-threatening.

Though I make no further recommendations, I want to conclude this section of my report by referencing the full statement that the family of Matthew Hines issued on the day that Fatal Response was tabled in Parliament. Their words are more powerful and convincing than anything else I can say or recommend on this subject at this time. It is my hope in giving voice to a family who have suffered so much that it will make some positive difference in ensuring that human life and dignity behind bars is preserved and protected as the law demands and Canadians expect.

Issues in Focus

Case 1: Delayed Response to Medical Emergency

- Following what appears to be an unprovoked and extremely violent inmate-on-inmate assault, in which the victim received several closed-hand punches and kicks to the head and torso, a number of correctional officers move in (while filming) to secure the area. The victim is seen lying unresponsive and motionless on the floor.

- The situation is quickly defused as correctional officers handcuff and escort the instigator from the scene. More than five minutes elapse before first aid is administered to the victim. During this time, several correctional officers are seen standing by, next to and even stepping around or over the victim. At one point, an officer appears to kneel down and look closely at the victim, yet emergency assistance is not initiated.

- Given the severity of the assault and the number of correctional officers who are seen standing around and appearing to be doing very little, it seems inconceivable that more than five minutes should lapse before any kind of emergency first aid is provided to the victim.

- The inadequate and delayed response to a medical emergency is compounded by the fact that health care services were not available on site to offer medical assistance because the assault took place after hours.

- Several minutes after correctional officers respond, paramedics arrive. The victim is admitted to outside hospital where he remains for five days in the intensive care unit.

Case 2: Use of Force Turned Medical Emergency

- An inmate was involved in a use of force incident in which an inflammatory agent (pepper spray) was deployed.

- Following the use of force, the inmate was escorted to the decontamination shower where he collapsed under medical distress (possibly as a result of an allergic reaction to the pepper spray).

- The camera operator, who was recording the decontamination shower, observed the inmate in distress (lying on the floor, gasping for air, coughing, spitting, at points unresponsive), yet continued to record, without intervening, for approximately seven minutes before finally calling for assistance.

- While the response was appropriate once initiated, the delay between recognition of a medical emergency and intervention was unacceptable. Additionally, at this institution, there was no after-hours medical staff on site, which resulted in further delay from the first signs of medical distress until outside Emergency Services arrived on scene.

Issues in Focus

Statement from the Family of Matthew Hines

For Immediate Release

Sydney, Nova Scotia: May 2, 2017

Earlier today, the investigation by the Office of the Correctional Investigator into the death of our son and brother at Dorchester Penitentiary on May 26, 2015 was tabled as a Special Report in Parliament by the Minister of Public Safety, the Honourable Ralph Goodale.

When the Honourable Ralph Goodale made a public statement last year that Canadians deserved answers about Matthews death, our lawyer wrote to the Minister to let him know that we were taking him at his word. The clear apology to our family, and most especially to our parents, that is contained in the government response to the Special Report tabled in Parliament today is extremely important to us.

Matthew struggled with mental health issues from the time he was an adolescent. There were few resources for youth and young adults with mental health issues in Cape Breton, and Matthew often found himself in trouble with the law.

In April, 2015 Matthew was living in the community on parole and, when his mental health was obviously deteriorating, we were told that he would get the help he needed if he returned to Dorchester Penitentiary. We believed that to be true. It was not.

Matthew was distraught at being sent back to the Dorchester Penitentiary and his last words to his sister Wendy were: Dont let them kill me.

Matthew died on May 26 th , 2015. We were told that Matthew died of a seizure. We were told that Matthew was a nice man who was loved by the correctional staff and that they were very sorry for his death.

Over a year later, we found out that Matthew died as a direct result of inexplicable and unnecessary physical and chemical force used by the correctional staff who were responsible for his care, and that this was captured in graphic detail on video. As is set out in the Special Report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator, the sheer number of correctional staff who were involved in or witnessed Matthews death is incomprehensible to us. Why did no-one prevent this from happening to him?

We are a large family of hard-working citizens who believe in this country and its institutions. We believe this because our parents raised us that way. The fact that our parents were not told the truth by their government about the circumstances that surrounded Matthews death is, to us, unforgiveable.

The Office of the Correctional Investigator has found that in Matthews case everything that could go wrong did go wrong. We are extremely grateful for the thorough and detailed investigation conducted by the Office of the Correctional Investigator. The commitment that they have shown in the investigation of Matthews death has given us hope that no-one else will suffer as Matthew did. Mr. Zinger travelled with his staff to Sydney to meet with us personally to explain his findings. The compassion and respect shown to us by Mr. Zinger and his staff, in our own home, will not be forgotten.

The Commissioner of Corrections has acknowledged and accepted all ten of the recommendations contained in the Special Report that has been tabled in Parliament. We are encouraged by this. We now await the conclusion of the renewed RCMP investigation into Matthews death, which was re-opened and transferred to Nova Scotia in the fall of 2016.

It is very important to us that Canadians understand Matthews story and understand the truth of what happened to him. No human being who is in prison should be physically and chemically abused by guards as Matthew was. And no human being should ever be ignored by medical personnel when they are in medical distress.

The fact that Matthew was treated with such indignity breaks our heart. We know that Matthew, for all of his struggles, would never have treated another human being that way.

3. Conditions of Confinement

Photo of different levels and ranges at Saskatchewan Penitentiary.

Riot at Saskatchewan Penitentiary

Photo of scattered debris from damaged cells in corridor of

Saskatchewan Penitentiary.

On December 14, 2016, a major riot took place in the medium security sector of Saskatchewan Penitentiary. At its height, close to 200 inmates were involved. Some inmates covered their faces with balaclavas. Range cameras were covered or destroyed, leaving officers with no means of observing events taking place on the ranges. One inmate was murdered. Eight others were taken to outside hospital with injuries sustained as a result of being assaulted, inhaling smoke or chemical agents or being struck by shotgun pellets used to suppress the riot. Damage to several units was extensive, leaving some uninhabitable.

Current research suggests that a lot must go wrong, and for quite some time, before a prison erupts in violence. Footnote 15 Such a perspective implies that prison administrators have opportunity and warning to address precipitating factors and thereby prevent a full-fledged riot from occurring in the first place. In other words, prison riots are not random or inevitable events; they are most likely to occur when a certain threshold of defiance and desperation is reached among a group of prisoners who take matters into their own hands to violently force change or express a long-standing grievance.

The immediate triggering events of the Saskatchewan Penitentiary riot appear to be related to unresolved demands regarding inmate dissatisfaction with food (shortages, replacement items, portion size and protein allotment), as well as perceived mistreatment of inmate kitchen workers (pay, hours, incentives) by CSC staff. When last-minute attempts to resolve these issues failed, tensions escalated. Demands and ultimatums were traded by both sides with inmates refusing to report to work and the Warden eventually ordering a lockdown of the institution. The start of the riot coincided with the call to inmate work at approximately 1:00 pm.

Though the cause(s) and circumstances of the riot are still under CSC investigation, the Office has requested that the Service review the factors that contributed, either directly or indirectly, to an environment of escalating tension, confrontation and eventual riot at Saskatchewan Penitentiary:

- Allegations of conflicts between CSC kitchen staff and inmate kitchen workers.

- Management interpretation and implementation of the National Menu Guidelines and inmate complaints relating to frequency and nature of food item shortages and substitutions; average daily food portion sizes; daily protein allotment.

- Identification and analysis of factors that may have contributed to overall inmate dissatisfaction and willingness to participate in a riot:

- Volume and nature of inmate complaints and grievances.

- Timely response to and resolution of systemic issues (e.g., inmate access to socials, tournaments and other privileges).

- Comparative analysis of use of force incidents, segregation placements, institutional charges, assaults and inmate discipline indicators.

- Frequency of disruptions in normal routine (lockdowns, inmate work refusals/protests, section 53 searches, access to visits).

- Quality and frequency of interactions between correctional staff and an overwhelmingly Indigenous inmate population (dynamic security).

Saskatchewan Penitentiary Riot, December 14, 2016.

Two page folio showing aftermath of the Saskatchewan Penitentiary riot on December 14, 2016:

- Clean up underway.

- Debris after riot

- Cell effects destroyed during riot.

- Damaged cell.

- Unexploded OC spray (pepper spray) munition.

- Damage and debris from riot.

- Debris in hallway after riot.

- Debris in range after riot.

- Damaged refrigerators in common area.

- Damage to walls from shotgun pellets and painted camera.

- Range view after riot

- Residue from OC spray (pepper spray) used by correctional officers.

- Clean up of debris from riot.

Issues in Focus

Saskatchewan Penitentiary Riot

Chronology of Events

13:15

Inmates from a number of ranges in the medium security sector of the institution refuse to attend work, programs or school.

13:30

Inmates on ranges E 1, 2, 3 and 4 tie off the range barriers with institutional blankets and clothing, barricade the barriers with fridges, washers and dryers in front of the range doors. Inmates cover their faces and destroy range cameras.

13:30

The Crisis Centre is mobilized and opened.

13:40

Emergency Response Team (ERT) members are called in.

14:07

Two negotiators begin negotiations on E3 and 4.

14:10

Inmates make weapons, dismantle beds, damage walls, breach an interior wall, smash windows and generally destroy property.

15:10

Inmates on F4 start fires on the range.

15:40

Deputy Warden reads the Riot Act via the all call system.

15:46

Inmates from F1 and 2 agree to negotiate and are willing to lock up.

16:35

ERT followed by line staff enter E3 and 4 ranges using necessary force (pepper spray and distraction devices) to gain compliance.

16:45

Inmates are removed off the range and assessed by first aid trained staff.

19: 25

The Institution is declared secure.

The Office has also requested that CSC account for the level and degree of force used to suppress the riot (more than 36 kilograms of pepper spray were deployed), including whether the use of firearms (shotguns) was proportionate, reasonable and necessary.

Immediately following the events of December 14, the Office dispatched two Senior Investigators to identify possible causes, as well as monitor and assess the response and situation in the riots aftermath. Several immediate areas of concern were noted, particularly with respect to personal health and hygiene (some prisoners had to sleep in contaminated clothing and bedding), provision of basic living necessities (showers, exercise), as well as access to legal counsel. At that time, the Office made three recommendations:

- Ensure food menus, recipes and portion size meet National requirements.

- Pursue and maintain an open dialogue between management and prisoners.

- Improve relations between CSC kitchen staff and inmate workers.

The Office continues to monitor the return to normal operations and routine at Saskatchewan Penitentiary. I would note positively the measures taken by management to deal with outstanding disciplinary charges arising from the riot, as well as special recognition of the extended period of lockdown and attendant disruptions in routine, visits, access to programs, etc. That said, the high number of complaints brought forward to our Office as well as continuing general unrest at this facility suggests that problems of a systemic nature persist. Incredibly, follow-up visits by this Office have noted continuing issues with food at this facility. I would also note that two of the largest penitentiaries in Canada (also two of the three oldest and arcane) Saskatchewan Penitentiary (1911) and Stony Mountain Institution (1877) are located in the Prairies region. Both institutions happen to house majority populations of Indigenous people. The antiquated conditions of confinement that prevail in these two institutions are not conducive to modern and humane correctional practice, nor responsive to the unique needs of Indigenous prisoners.

- I recommend that the lessons learned from the National Board of Investigation into the December 2016 major disturbance at Saskatchewan Penitentiary be widely circulated within CSC and released as a public document.

Issues in Focus

Legal Implications of the Riot Act Proclamation

- According to the Criminal Code of Canada, a riot is an unlawful assembly that has begun to disturb the peace tumultuously.

- Section 67 of the Criminal Code provides that the Warden or Deputy Warden of a penitentiary, upon receiving notice that twelve or more persons are unlawfully and riotously assembled together, may order the inmates to cease their assembly and disperse.

- When such conditions are met, the Riot Act may be read, which is issued in the following words or words to like effect:

Her Majesty the Queen charges and commands all persons being assembled immediately to disperse and peaceably to depart to their habitations or to their lawful business upon the pain of being guilty of an offence for which, upon conviction, they may be sentenced to imprisonment for life. GOD SAVE THE QUEEN.

- The Riot Act imposes an obligation for the correctional authority to disperse or arrest persons who do not comply with the Proclamation.

- No civil or criminal proceedings can be taken against any officer in respect of any death or injury caused by inmate resistance against the suppression of the riot.

- Further, any person who resists or does not disperse within 30 minutes of reading of the Proclamation is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for life.

Prison Food

As one of the factors that sparked the deadly Saskatchewan Penitentiary riot, food is foundational to health and safety in a prison setting. The HM Inspectorate of Prisons in the United Kingdom recently reported that the low quality of food being served in British prisons, combined with small portion sizes, could serve as a catalyst for aggression and dissent. Footnote 16 The Inspectorates report also found that various medical complications attributable to poor nutrition, including nutritional deficiencies, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and high cholesterol, added to rising prison health care costs.

Photo of vegan meal under National Menu.

Photo of regular meal.

As in the UK, spending on food in Canadian prisons has been decreasing. As part of CSCs contribution to the previous governments Deficit Reduction Action Plan (DRAP), the Service implemented its Food Services Modernization initiative, resulting in total net savings of $6.4M. Core elements of the initiative involved implementation of a National Menu and regional Cook Chill production centres where food is prepared, cooked and chilled in a centralized kitchen. Food is prepared in industrial-sized kettles and tanks up to two weeks in advance, chilled in bulk packaging, stored frozen then shipped to the institutions for retherming. Finishing kitchens add food items to the meal that must be prepared or served fresh.

Photo of an industrial kitchen at Bath Institution.

Photo credit: Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights.

Under the National Menu, the daily cost for food allotted to each inmate is fixed at $5.41. Standardized national recipes are used and weekly menus are followed. Each inmate is given 2,600 calories, which, according to Canadas Food Guide, is sufficient for a low-activity male aged 31 to 50. Footnote 17 Meeting the low daily ration cost, while still complying with minimum nutritional requirements and the standardization of the National Menu, required CSC to find ways of lowering raw food input costs. Among other measures, powdered milk was substituted for fresh milk, bulky meat portions replaced more select cuts, expensive grains were removed, vegetable selection was reduced and English muffins were replaced with toast.

Photo of shelves of freshly baked loaves of bread.

Photo of plates and cutlery on a table after a meal.

Not surprisingly, when these changes were first introduced, inmate grievances related to food issues spiked. As food services modernization was a nationally-directed initiative, inmate complaints and grievances related to food at the local level have largely been passed onto the national level of review and redress. Though the internal grievance rate on food issues is gradually returning to more normal levels as Wardens make local adjustments, it remains elevated. This Office is still receiving complaints related to food portion size (especially protein), quality, selection and substitution of items. Young men (up to age 30), who still make up the majority population in federal penitentiaries, require more than average number of calories and protein and that simply means more food. In some institutions, food has become a commodity that requires monitoring as it can be bartered, sold or traded for other items, including contraband. Playing with the food of hungry and frustrated prisoners can have unintended detrimental effects.