June 25, 2019

The Honourable Ralph Goodale

Minister of Public Safety

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 46th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigators Message

1. Health Care in Federal Corrections

2. Prevention of Deaths in Custody

5. Safe and Timely Reintegration

Correctional Investigators Outlook for 2019-20

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Correctional Investigator's Message

Dr. Ivan Zinger,

Correctional Investigator of Canada

I am mindful that the function my Office serves - to act as an ombudsman for federally sentenced offenders - is not particularly well known and frequently misunderstood, sometimes even within the agency subject to my oversight. I fully understand and accept that the business of prison oversight, standing up for the rights of sentenced persons and advocating for fair and humane treatment of prisoners are not activities that are widely recognized or praised. Yet, to turn a phrase made famous by a young Winston Churchill, if prisons are places where the principles of human dignity, compassion and decency are stretched to their limits, then how we treat those deprived of their liberty is still one of the most enduring tests of a free and democratic society. Independent monitoring is needed to ensure the inmate experience does not demean or degrade the inherent worth and dignity of the human person. There are very few dedicated ombudsman bodies specializing in this kind of work anywhere in the world, and I take enormous pride in leading the Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada.

When meeting with senior Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) management I am often asked a familiar, if somewhat rhetorical question - "why don't you ever say something nice about us, or mention our successes"? I will often answer with a standard comeback to the effect that "because the legislation directs that I investigate problems or complaints of offenders related to decisions, acts or omissions of the Service." Part III of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , which spells out the function and mandate of my Office in legislation, neither directs me to praise or criticize the Correctional Service. Though my Office is often reduced to or misconstrued as a critic, advocate or watchdog agency, none of these terms does adequate justice to 'righting a wrong' by seeking resolution of complaints and systemic issues at their source.

Since assuming my duties, I have taken a special interest in identifying conditions of confinement and treatment of prisoners that fail to meet standards of human dignity, violate human rights or otherwise serve no lawful purpose. The issues investigated and highlighted in my report raise fundamental questions of correctional purpose challenging anew the assumptions, measures and standards of human decency and dignity in Canadian prisons:

- Introduction of a standardized "random" strip-searching routine and protocol (1:3 ratio) at women offender institutions.

- Staff culture of impunity and mistreatment at Edmonton Institution.

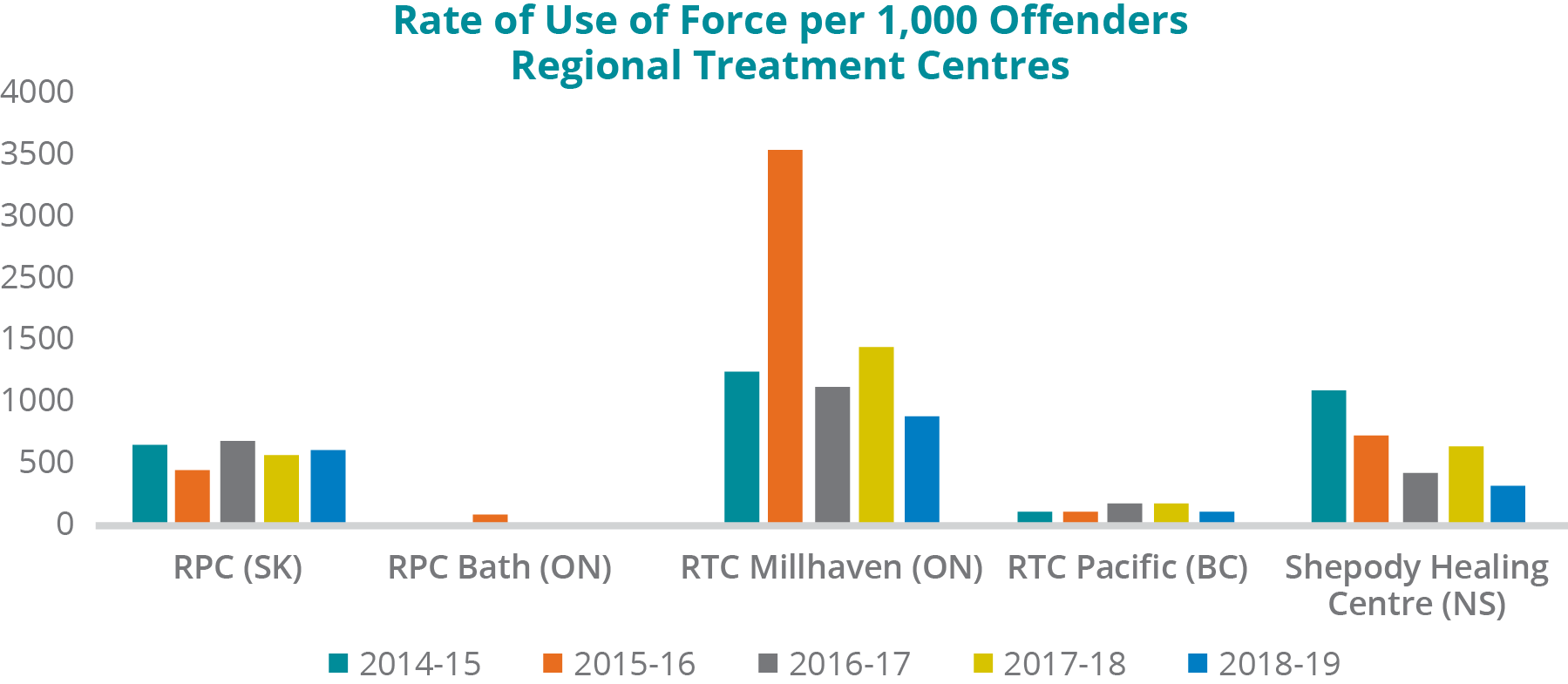

- Elevated rate of use of force incidents at the Regional Treatment Centres (designated psychiatric hospitals for mentally ill patient inmates).

- Lack of in-cell toilets on one living unit at Pacific Institution.

- Provision of the first medically assisted death in a federal penitentiary.

- Prison food that is substandard and inadequate to meet nutritional needs.

- Operational challenges in meeting the needs of transgender persons in prison.

- Housing maximum-security inmates with behavioural or mental health needs on "therapeutic" ranges that serve segregation diversion ends.

Many of the practices noted above would seem to run counter to the vision articulated in the Government's Mandate Letter issued to the newly appointed Commissioner of Corrections by the Public Safety Minister in early September 2018. This was the first time that a mandate letter from the government to the Deputy Head of the Correctional Service was made public. As such, it is an important expression of the Government's intention to move forward with a comprehensive correctional reform agenda. Making these commitments public marks a significant step forward in improving accountability and transparency within CSC. I support and commend the effort.

I would point out that several of the mandate commitments have been the focus of previous Office reporting including:

- Minimize barriers to prison visits, increase inmate contact with the outside world, and provide inmate access to supervised use of email.

- Prioritize education behind bars, implement digital learning platforms, and enhance offender access to post-secondary opportunities.

- Prohibit placement of inmates with mental health problems in segregation.

- Treat addiction as a health issue and ensure continuity of care upon release.

- Respect the full diversity of CSC's population, including Indigenous, Black Canadians, women, young adults, LGBTQ2 individuals, aging and elderly persons in prison.

- Enhance the use of Indigenous specific legislative provisions to address gaps and overrepresentation of Indigenous people in corrections.

In this year's report, relevant chapters on health care, conditions of confinement, Indigenous corrections, safe and timely reintegration and federally sentenced women touch on other mandate commitments to:

- Implement a safe needle exchange program in federal prisons.

- Adhere to the principles of Creating Choices in women's corrections.

- Provide nutrition adequate in quality and quantity to support well-being.

- Focus vocational programming on skills development linked to employability.

- Ensure CSC is a workplace free from bullying, harassment and sexual violence.

- Instill within CSC a culture of ongoing self-reflection.

- Ensure use of force incidents are investigated fully and transparently, and lessons learned implemented.

- Work with Indigenous partners to increase support for Healing Lodges and community-supported releases under Section 84.

- Examine the role of the National Aboriginal Advisory Committee.

As my report suggests, many moving and unaligned parts will need to come together for the current government's vision for federal corrections to be realized. The Minister acknowledges that some of these mandate initiatives may require new policy authorities (e.g., segregation reform) or additional funding.

However, a review of current resource allocation levels conducted by my Office suggests that there is considerable room to reallocate internally within the Correctional Service in order to meet new demands on programs and service delivery driven by changes in the diversity and distribution of the federal offender population.

According to Statistics Canada, in 2017-18, it cost $330 per day or $120,571 per year, to keep a federally sentenced individual behind bars. With a staff-to-inmate ratio of 1:1, CSC is among the highest resourced correctional systems in the world. Additional funding announced in December 2018 could add as many as 1,000 new staff to its ranks, most of them being Correctional Officers. While I acknowledge that there are definitional and methodological challenges in making international comparisons, by my estimates Canada could soon have the highest staff-to-inmate ratio in the world. Footnote 1

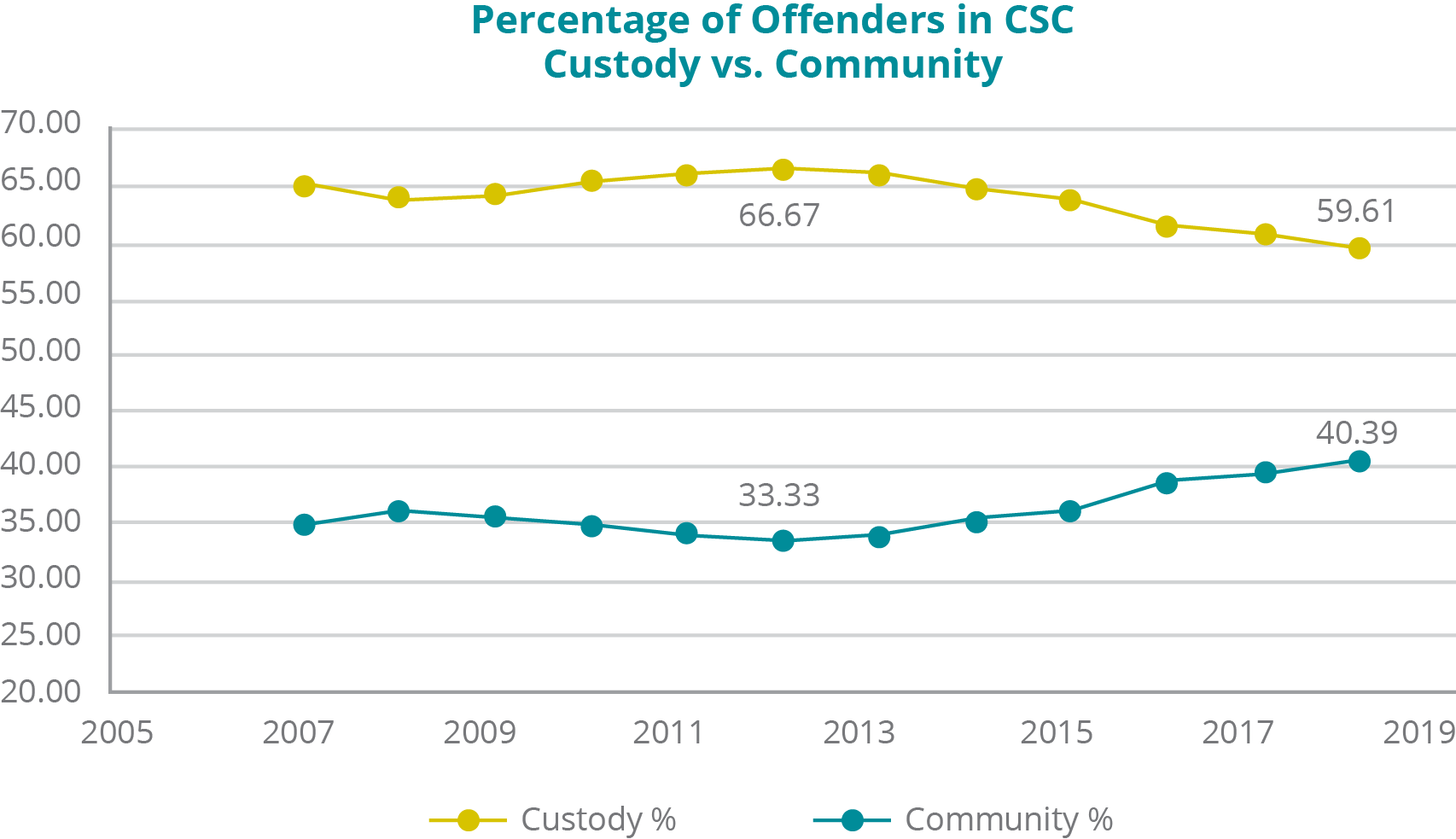

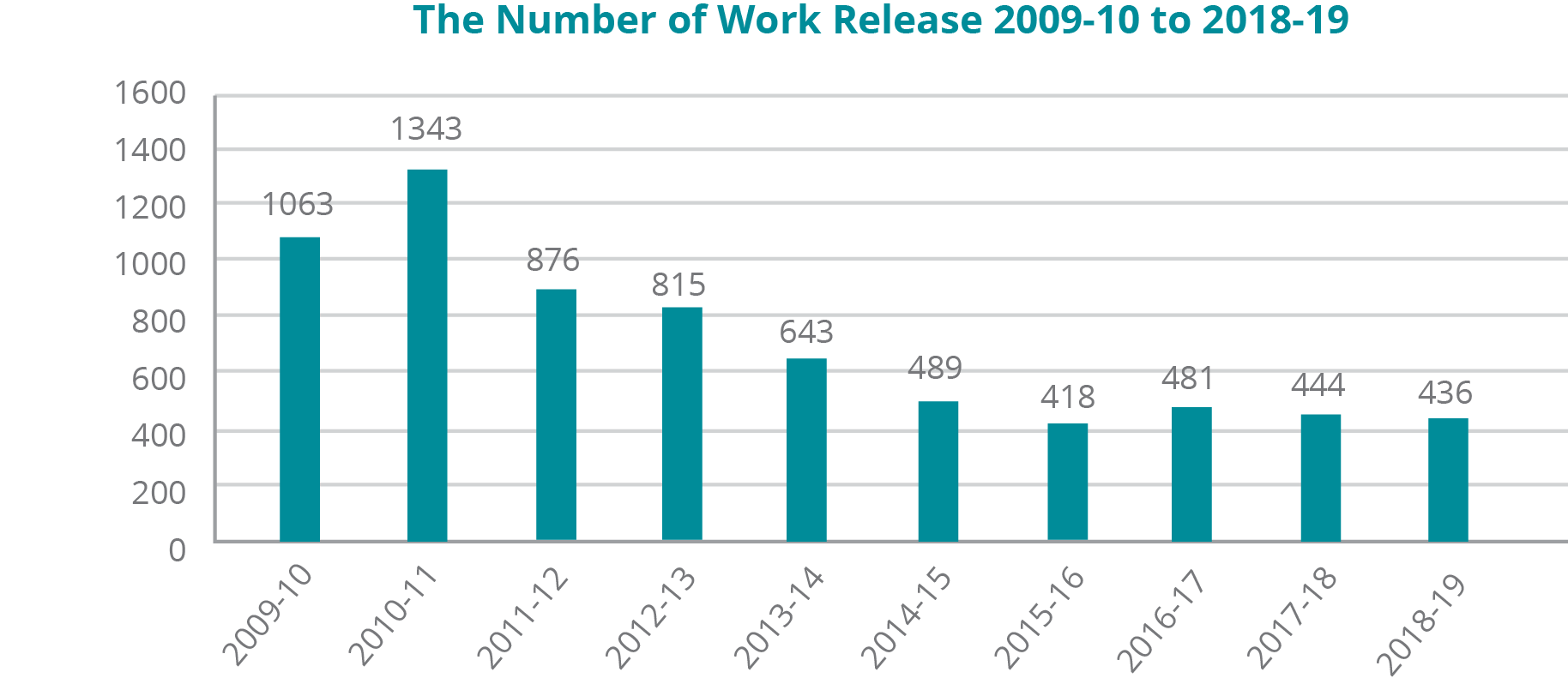

Meantime, the number of inmates in prison today has declined from a high of 15,340 reached in 2013, and currently stands at almost the same number as ten years ago (a little over 14,000 incarcerated). By contrast, the number of offenders under community supervision increased from around 7,700 in 2013 to 9,200 today. Since 2007-08, CSC added approximately 1,200 correctional officer positions to its roster; its total staff complement has increased by over 2,500 employees - 80% of which were front-line security staff. Today, nearly four in ten prisons have more full-time employees than inmates. In some institutions, the number of Correctional Officers alone exceeds the number of inmates. There are approximately 2,000 prison cells now sitting vacant across the country, which represents the difference between a total rated capacity of 16,382 and a current inmate population of 14,081.

With current spending, investment and staffing levels, Canada should be outstanding in every aspect of correctional performance. As my report indicates, there is room for considerable improvement. 2018-19 marked the highest number of inmate-on-inmate assaults, as well as inmate-on-staff assaults. Use of force incidents were the highest ever recorded in CSC facilities. The rate of self-inflicted injuries also reached new heights, both in terms of frequency and number of inmates engaging in self-injurious behaviour behind bars. There were five prison homicides in 2018-19, the highest in a decade. As noted, these outcomes were posted at a time when new and returning admissions to prison are declining and the community supervision population is surging to new levels. Despite changes in the distribution of the offender population, CSC only allocates 6% of its total budget to supervision of offenders in the community. Comparatively, the ratio of offenders to community supervision staff is around 6.5 offenders per community staff member.

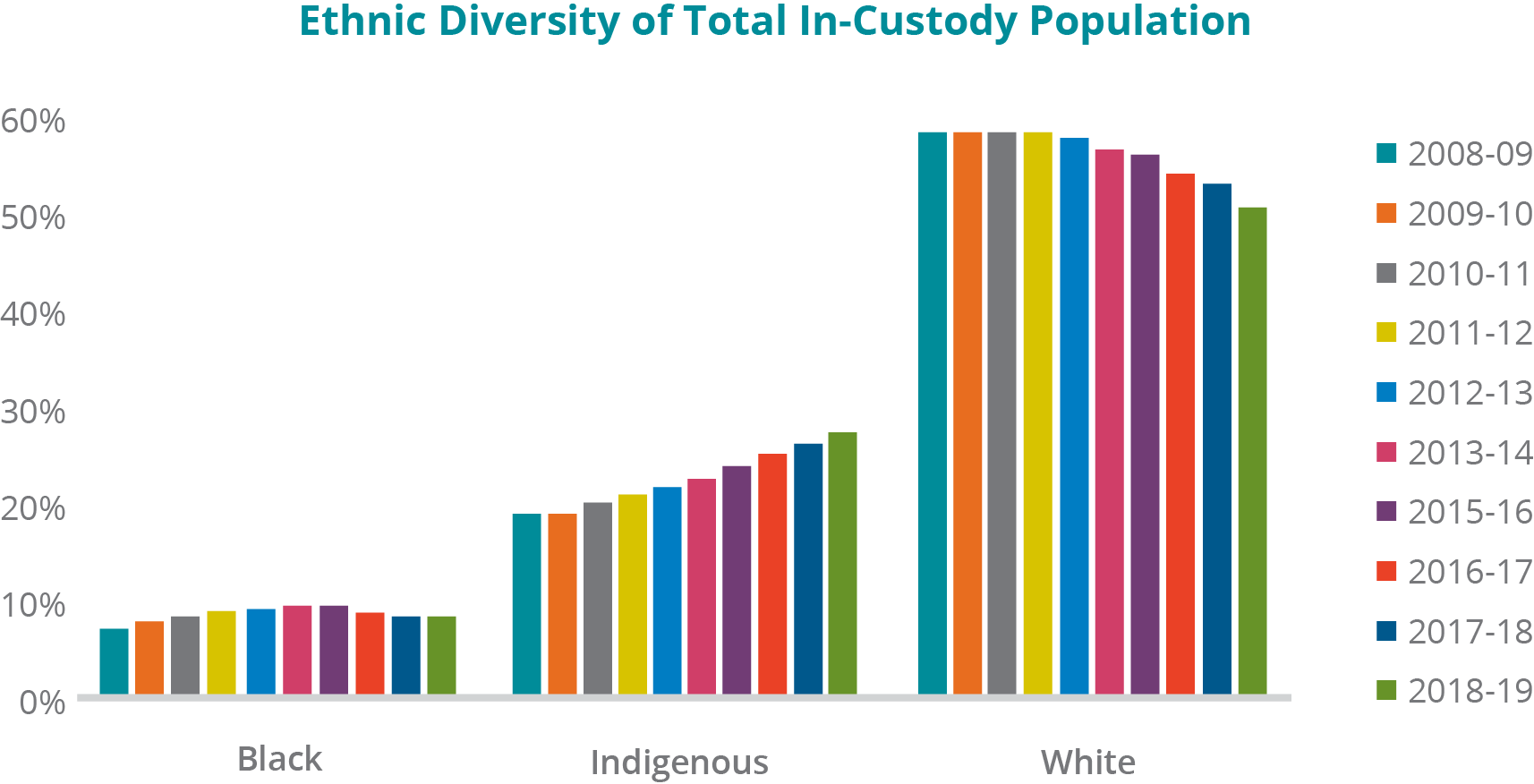

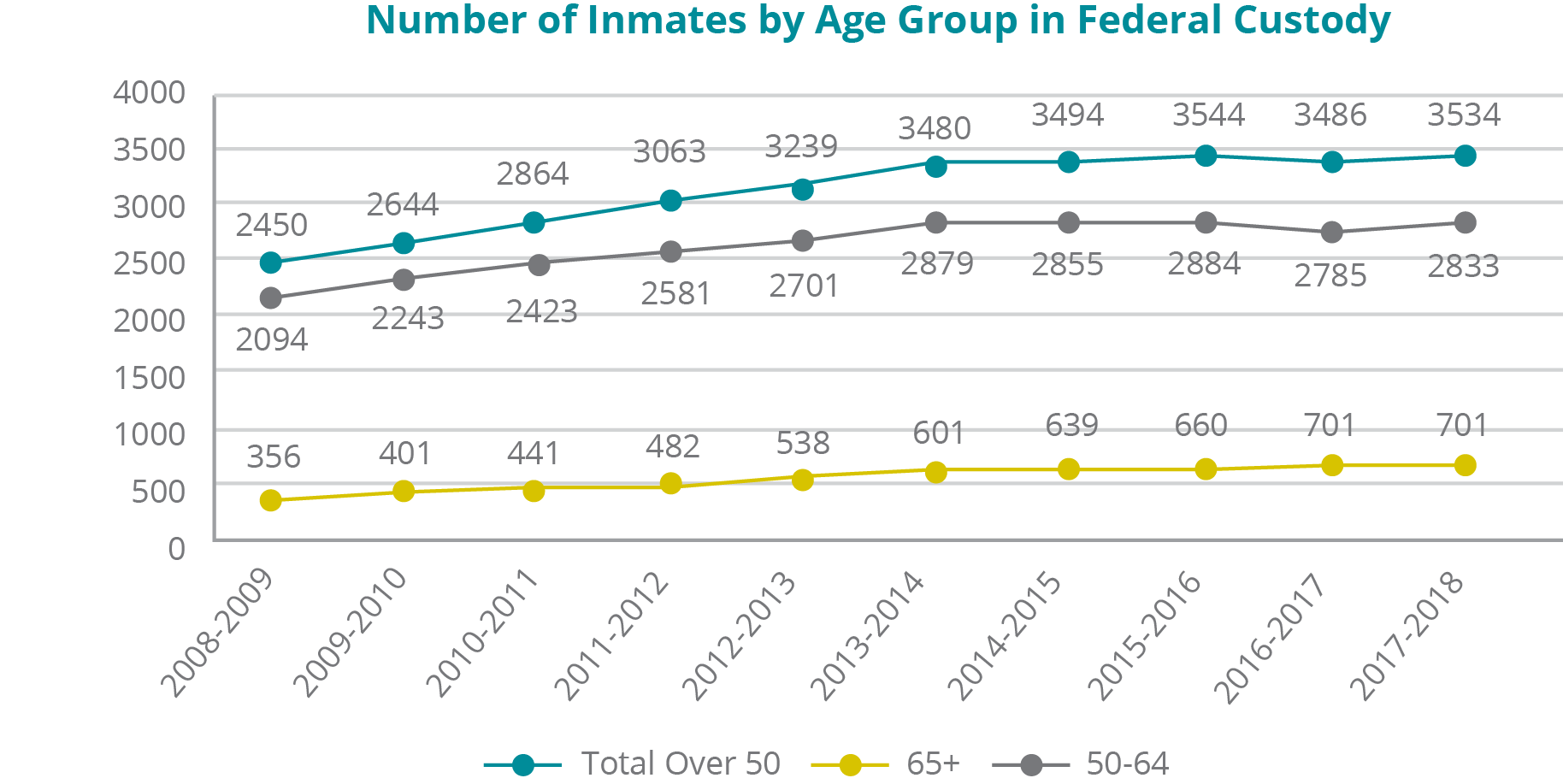

Over the last decade, there has been effectively no new net growth in the total population under federal sentence, yet the distribution of that population has changed in some rather dramatic ways. For example, the Indigenous portion of the incarcerated population has grown by more than 50% overall and 74% for in-custody Indigenous women. CSC resources and priorities have not flowed in proportional or relative terms to meet the urgency of a crisis of over-representation of Indigenous people in federal corrections or address outcomes that are differentially and substantially worse for Indigenous offenders.

Other population drivers and dynamics of change would also suggest that resources should be allocated to areas that demonstrate the greatest pressure and need in order to increase efficiency and enhance outcomes. Three areas, in particular, should be examined for reallocation from institutional to community corrections:

- Indigenous corrections (specifically Section 81 and 84).

- Alternatives to incarceration for seriously mentally ill offenders.

- Aging and elderly offenders (particularly those who, due to poor or declining health and time-served, pose no undue risk to society).

The Government's mandate letter closes by encouraging the Commissioner to instill within CSC a "culture of ongoing self-reflection," a professional approach and attitude that would welcome "constructive, good-faith critiques as indispensable drivers of progress." These are refreshing and encouraging messages, and my report provides a number of case studies that could contribute to a more self-reflective corporate culture that embraces new and different ways of thinking, learning and behaving. Indeed, if there is a recurring or unifying message to this year's report, it is that CSC's organizational "culture" - the patterns of beliefs, assumptions, norms, codes of conduct, and ways of thinking and doing that define how an organization acts and behaves - has become too insular, rigid and defensive. A professional culture that has grown wary and resistant to change, a practice steeped in a tired and worn belief that "this is the way we do things here," are holding the Service back from becoming the best it can be. It is not within my mandate to fix workplace or labour relations issues, but it is my responsibility and duty to report on them when they create adverse effects for offenders or otherwise jeopardize fair and humane treatment.

I remain committed to working collaboratively and constructively with the Minister and Commissioner in meeting the government's correctional reform agenda for Canada.

Ivan Zinger, JD., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

June 2019

1. HEALTH CARE IN FEDERAL CORRECTIONS

Medical Service Delivery Vehicle - La Macaza

United Nations Special Rapporteur on the 'Right to Health'

On November 6, 2018, I had the privilege to meet with Mr. Dainius PÅ«ras, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the 'Right to Health.' At our meeting, I explained that federal offenders are excluded from the Canada Health Act and not covered by Health Canada or provincial health care systems. I emphasized that CSC has a legal obligation to ensure reasonable access to essential health care in conformity with professionally accepted standards of practice, and that an offender's state of health and health care needs must be considered in all decisions (e.g., placements, transfers, segregation, etc.).

In our discussions, I provided the following summary of health care concerns in federal corrections:

- Canadian compliance with the United Nations 'Mandela Rules' pertaining to the role of health care services and health care providers.

- Equivalence in standards and delivery of health care between community and corrections.

- Clinical independence and autonomy of correctional health care providers.

- Use of force involving inmates with mental health issues.

- Psychological and behavioural effects of isolation, seclusion and solitary confinement.

- Premature death and dying with dignity behind bars.

- Management of complex mental health needs.

Banner and logo of the United Nations

Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner

Our positions seemed to converge on these and other areas of domestic and international health care concern and reform. Though the Special Rapporteur's final report is scheduled to be released outside the production phase of this Annual Report, his preliminary observations from his Canadian visit were released on November 16, 2018. Footnote 2 In this statement, Mr. PÅ«ras highlights the fact that Canada has "yet to ratify important treaties, including the Optional Protocol [to the Convention against Torture ] that would allow individuals to submit complaints on alleged violations of the right to health." He goes on to commend Canada's public health approach, but also identifies shortfalls stating that "Canada is yet to take the leap to comprehensively incorporate a right to health perspective, fully embracing the understanding that health, beyond a public service, is a human right."

From this light, barriers to accessing adequate health care become a question of justice. I concur with this perspective. Moreover, I would argue that human rights are violated whenever detained people are stigmatized or punished for behaviours stemming from underlying health or mental health factors.

Therapeutic Ranges (Maximum Security)

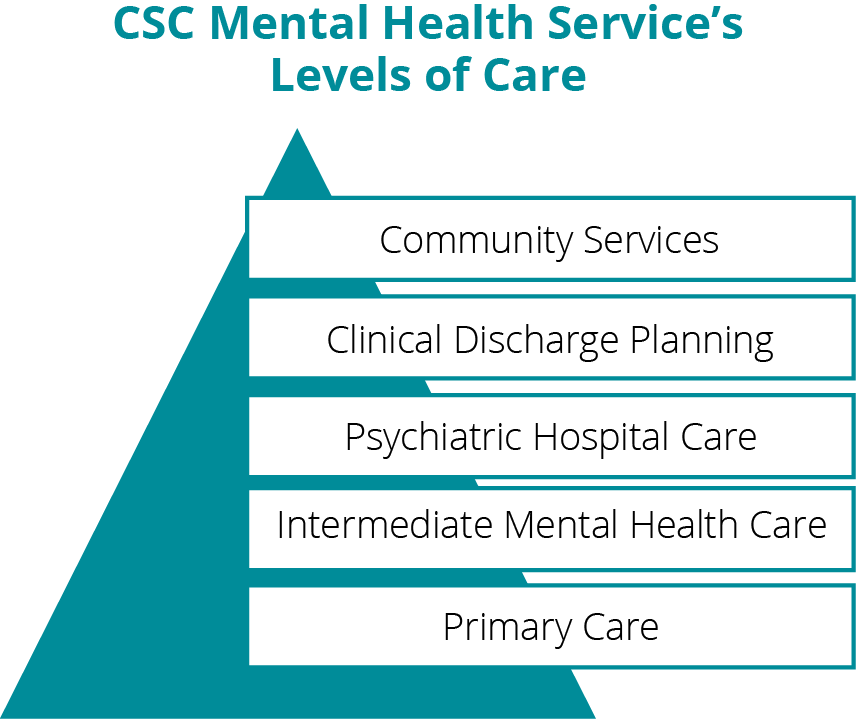

Therapeutic Ranges are intended to offer moderate intensity Intermediate Mental Health Care services at maximum-security sites. Footnote 3 They are used to manage maximum-security inmates who do not meet the admission criteria of Treatment Centres, or whose behavioural or security requirements cannot be safely met in a psychiatric hospital setting. First introduced in 2017-18, the admission criteria for these ranges include individuals who:

- Present with moderate impairment or significant mental health symptoms.

- Require more than what can be offered through Primary Care.

- Do not require 24-hour care.

- May also pose challenging behaviours that are secondary to their mental health needs, and often have heightened security requirements.

As stated in CSC's Corporate Business Plan, Therapeutic Ranges aim to provide a "therapeutic alternative" to segregation for offenders who engage in challenging behaviours that are secondary to mental health concerns.

That is, the current model intends to divert offenders with mental health needs away from administrative segregation and onto therapeutic units where they can receive programs, services and treatment.

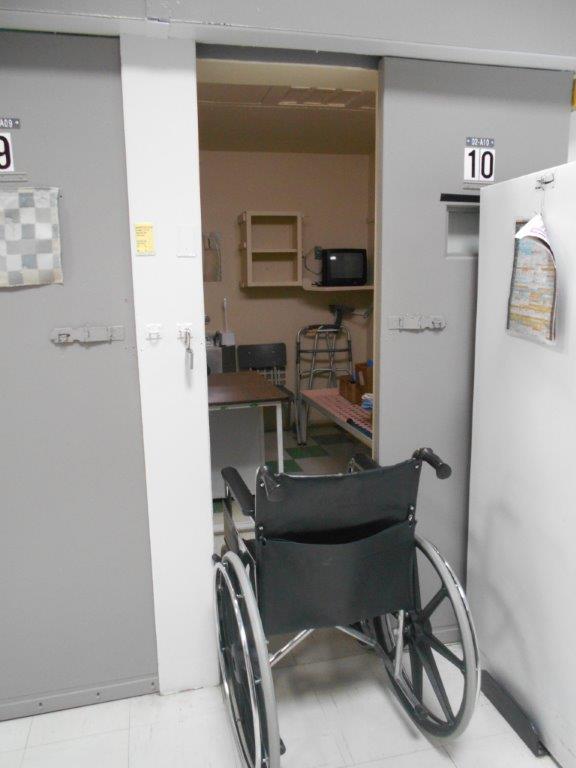

Therapeutic Range -

Atlantic Institution

In Budget 2017, CSC was allocated $58M in additional resources to expand mental health care capacity in federal corrections. Part of that new funding (just over $10M) was reserved for implementing and operating Therapeutic Ranges (over a five-year period) at maximum-security facilities in each of CSC's five regions. Footnote 4 To date, Therapeutic Ranges have been opened at the following maximum-security institutions: Atlantic, Kent and Edmonton Institutions. CSC has reported its intentions to proceed with the ongoing implementation of Therapeutic Ranges in the Quebec and Ontario regions. Footnote 5

A preliminary review and site visits by my Office suggest that CSC's implementation of these ranges may not fully align with mental health care objectives. For example, the additional funding received by Atlantic Institution for its Therapeutic Unit was used to create four "Therapeutic Officer" positions classified as CX-02 (Correctional Officer). It is not clear how these positions differ from front-line security staff, except for some additional training in mental health. Furthermore, as the photos illustrate, in infrastructure terms, the Therapeutic Unit is substantially no different from the Segregation Unit at Atlantic Institution. The situation seems more or less the same at Edmonton Institution.

In March 2019, my Office requested detailed information about the mental health services, supports and interventions that are offered on these ranges and the staffing and operational model upon which they are premised. In June 2019, CSC responded, noting that, because of new funding, each region now has one maximum-security site that can provide intermediate level mental health care. There are 110 therapeutic range beds at five sites, which represents about 6% of the total male maximum-security population. The resourcing and staffing model appears based on a 20-bed unit. For individuals on these ranges, the daily routine is similar to other maximum-security facilities, except for participation in group or individual clinical interventions.

Segregation Unit - Atlantic Institution

In the absence of information or evidence provided by CSC to the contrary, I am led to the preliminary conclusion that Therapeutic Ranges in maximum-security institutions serve more as a segregation diversion strategy than enhancement of mental health treatment capacity. On the face of it, there seems to be little clinical value for employing this model over other segregation diversion/intervention strategies. Although the research on providing interventions to segregated inmates is sparse it does exist, Footnote 6 and it would be prudent for the Service to draw on the experience of other jurisdictions. There may even be valuable lessons to be gleaned from its own experience in attempting to implement the Segregation Intervention initiative, Footnote 7 which faced numerous operational challenges and failed to achieve most of its expected aims.

Frankly, it is unclear what the new funding for Therapeutic Ranges has been used for, or even what results they are expected to achieve other than diverting maximum- security inmates with challenging behaviours away from segregation. More importantly, I do not see how these environments could be expected to serve any therapeutic aim. Going forward, it is even less clear what purpose these ranges will serve once segregastion is eliminated. Based on the experience to date, Therapeutic Ranges should serve as a cautionary tale for how CSC plans to manage inmates with mental health needs or behavioural needs in a post-segregation era. I intend to conduct a more in-depth review of these ranges in the coming year, including clinical care coordination, individual treatment plans and case progress reports.

Use of Force at the Treatment Centres

In the aftermath of the tragic and preventable death of Matthew Hines at Dorchester Penitentiary in October 2015, Footnote 8 CSC invested considerable effort to develop and implement a more "person-centred" approach to managing security incidents called the Engagement and Intervention Model (EIM). According to CSC, the EIM emphasizes "the importance of non-physical and de-escalation responses to incidents and to clearly distinguish response protocols for situations involving physical or mental health distress." Footnote 9 As outlined in Commissioner's Directive (CD) 567, Management of Incidents , these response protocols include:

- Take into consideration the inmate's mental and/or physical health and well-being, as well as the safety of other persons and the security of the institution.

- When possible, promote the peaceful resolution of the incident using verbal intervention and/or negotiation.

- Be limited to only what is necessary and proportionate.

- Take into consideration changes in the situation with continuous assessment and reassessment.

- When evaluating a response, staff will consider the many partners available [such as health care professionals] to create collaborative and appropriate interventions.

- Staff presence will be used generally and strategically to prevent and resolve incidents. The mere presence of a staff member demonstrating positive attitudes and behaviours can serve to de-escalate a situation.

Although I concur with these protocols in theory, I am not satisfied with how they are applied in practice. Since promulgation of CD 567 in January of 2018, my Office continues to review incidents of unnecessary and/or inappropriate uses of force in federal institutions. Some of the most troubling use of force incidents involve inmate-patients residing at the Regional Treatment Centres (RTCs) or psychiatric hospitals.

Use of Force Incident at Millhaven Regional Treatment Centre (RTC)

Range video evidence shows an inmate, diagnosed with a serious mental health disorder with significant impairments, engaged in a therapeutic interview with a Behavioural Technologist (BT) in the recreation room. During the interview, he asks an officer standing nearby at the control post if he could go to the yard for recreation after the interview. The officer declines, explaining that due to ongoing maintenance work the inmate would have to wait until later.

The inmate becomes agitated, directing a verbal protest towards an officer standing just outside the barrier of the recreation room. The officer's response further escalates the situation. While the BT attempts to de-escalate through verbal coaching, without warning or consultation, officers decide to discontinue the interview due to alleged "staff safety concerns". The BT's report would later state that at no point did s/he feel the inmate had put anyone's safety at risk, and that the inmate was "appropriate and polite" in all interactions.

An officer opens the barrier and orders the BT "get out of here." The BT attempted to leave the area; however, a group of four other officers had already gathered at the exit. The inmate lunges toward the officers attempting to strike one of them. The officers charge, tackling him to the floor. The inmate is held down by the weight of the four officers while lying prone. A nearby health practitioner reports later that an officer was kneeling across the inmate's neck and that his face was purple. The inmate is seen gasping. One of the officers is reported to have said, "want me to jizz on your face?" The others are seen laughing on video.

The inmate is handcuffed while on the ground and then lifted and slammed against a steel door, his head pressed against it while being held from the back of his neck. He is searched while restrained in this position. He is then escorted, without incident, to an observation cell.

Still handcuffed, he is forced onto the cell bed in a prone position with his face planted firmly onto the metal surface until his handcuffs are removed. The last officer to exit the cell is seen pinning the inmate's head to the bed and applying a "pain compliance" technique (forceful twisting and stretching of the arm and wrist) to maintain control as he exits the cell.

Inmate lying prone on

floor with four officers on top of him

- RTC Millhaven

Inmate pressed against

steel door while being handcuffed

- RTC Millhaven

The incident at Millhaven RTC is not an isolated case. Indeed, in 2018-19, my use of force review team identified a trend of inappropriate and/or unnecessary use of force incidents at Millhaven RTC. In the last fiscal year, the proportion of use of force incidents at Millhaven RTC deemed by my Office to be inappropriate and/or unnecessary was much higher (28%), compared to the proportion for all institutions (13%). Remove Millhaven RTC from the estimate and the overall national proportion drops to 9.3%.

As a whole, the five Treatment Centres accounted for roughly 20% of all use of force incidents reviewed by my Office in 2018-19 (296 out of 1,546). One out of ten incidents at the Treatment Centres was deemed unnecessary and/or inappropriate. Millhaven RTC accounted for 80% of these.

The level and rates of use of force at the Treatment Centres raise a familiar issue, namely, the competence and training of security staff. I raised this concern in my last Annual Report recommending that: "CSC ensure security staff working in a Regional Treatment Centre be carefully recruited, suitably selected, properly trained and fully competent to carry out their duties in a secure psychiatric hospital environment." CSC responded that, "All correctional staff, including those who are working in Regional Treatment Centres, are carefully recruited, selected and trained." The incident featured in the Case Study and rates of inappropriate/unnecessary uses of force at Millhaven RTC would suggest otherwise.

Source: Correctional Service of Canada, (April 2019). Performance measurement

and management reports.

CSC's internal reviews of the Case Study incident concluded that - among numerous other policy violations - the use of force was not necessary and the amount of force used was not proportionate to the situation. I was pleased to hear that the institution took swift disciplinary action against the officers involved. These are important accountability measures, but post-incident reviews are not enough to ensure staff compliance with the EIM protocols. As RTCs are psychiatric facilities treating patients, every effort should be made to ensure force is used only when necessary.

During site visits, OCI investigative staff have noted the trend of front-line security staff at Treatment Centres sitting behind a desk or barrier largely disengaged with inmate patients. In fact, the majority of interactions between patients and correctional staff appear to be prompted by patients. This kind of security posture reinforces an "us-versus-them" culture at odds with the therapeutic aims of the Treatment Centres.

- I recommend that, in 2019-2020, CSC conduct a review of security practices and protocols that would ensure a more positive and supportive environment within which clinical care can be safely provided at the Regional Treatment Centres. This "best practices" review would identify a security model and response structure that would better serve the needs of patients, support treatment aims of clinicians and meet least restrictive principles of the law.

CSC Response:

Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) committed to completing an evaluation of the Engagement and Intervention Model (EIM) in response to the Office of the Correctional Investigator's (OCI) 2017-2018 Annual Report. The evaluation is currently being undertaken and will provide information on achievements against expected results including those at Treatment Centres.

It is acknowledged there is an opportunity to look at security and health services protocols related to de-escalation and intervention activities, and build on best practices, to ensure the needs of patients are appropriately supported taking into account principles of least restrictive measures consistent with the protection of society, staff members and offenders. To this end, CSC will establish a forum with representation from CSC stakeholders.

SUMMARY OF RESEARCH: INJECTION DRUG USE AMONG FEDERALLY SENTENCED OFFENDERS

- 30% of women and 21% of men reported lifetime injection drug use. Of those who did, 53% of women and 39% of men reported sharing needles. Footnote 10

- 51% of all men who reported lifetime injection drug use indicated recent injection drug use, and almost all of these individuals (94%) were assessed with a moderate to severe drug dependency problem. Footnote 11

- The odds of self-reported HIV and HCV, among male offenders, was found to be significantly elevated among those reporting lifetime injection drug use, compared to those who never injected drugs. Footnote 12

Prison Needle Exchange Program

In June 2018, CSC launched a Prison Needle Exchange Program (PNEP) at two federal institutions: Atlantic Institution in New Brunswick and Grand Valley Institution for Women in Ontario. Among other objectives, the purpose of the PNEP is to reduce the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis C. The Service began a planned national roll out of the PNEP (one site per month) in January 2019. As of spring 2019, the program had been implemented in all five of the regional women's facilities, as well as Atlantic Institution for men. A "phased" approach to implementation was adopted, ostensibly so that CSC can learn and adjust from experience gained from other sites.

Though I am encouraged by the decision to move forward with the implementation of PNEP in federal corrections, I have several concerns about the approach adopted so far. Harm reduction strategies can only be successful if there is uptake on the part of users, and the way that the PNEP has been developed and implemented thus far seems to have built-in restrictions to enrollment. As of April 2019, perhaps not surprisingly, there were only a handful of individuals enrolled in the program.

Some elements of the program appear confusing or even contradictory. Currently, the program works on a one-to-one syringe exchange, which does not necessarily respect clinical need or demand. According to the contract that PNEP participants are obliged to sign, "disciplinary measures will continue to be implemented if the inmate is found to be in possession of illicit drugs or drug paraphernalia (except for the PNEP kit and supplies provided)." PNEP kits can be seized if the syringe or needle is altered, missing or observed outside the kit. In other words, a zero tolerance approach to drug possession in CSC facilities remains in effect. Drugs and drug paraphernalia (except official CSC-issued PNEP kit and supplies) are still considered contraband items, subject to disciplinary measures.

There are other possible explanations for low participation. When first implemented, the Parole Board of Canada (PBC) deemed all information regarding PNEP participation as "relevant to release decision-making," meaning that this information must be shared with PBC. The PBC has since removed this requirement. The program is open to criticism that it is driven by security versus clinical need:

- Use of a Threat and Risk assessment as a condition of PNEP participation (same for access to other "sharps").

- Access to needles/syringes not determined by need (one-to-one needle/syringe exchange).

- Lack of multiple access and distribution points (must return used needle to Health Services).

Confidentiality is breached by requiring participants to show a kit for visual inspection during the daily stand-to-count, and upon request. That said, it is not clear that participation in a program of this nature in a prison context could ever be entirely confidential, much less anonymous. The daily pill parade and direct observation requirement for dispensing certain "high risk" medications are far from confidential or anonymous procedures. In a prison setting where everyone knows everybody else's business, the concern about confidentiality can be mitigated, but not entirely eliminated. Even still, patient confidentiality and "need to know" principles need to be respected to the extent possible. If these concerns are not adequately addressed, limited program uptake and participation is expected, and has been observed.

Union of Canadian Correctional Officers

(UCCO) picket against Needle Exchange

Harm reduction cannot be effective without buy-in of both users and providers. An effective harm reduction strategy recognizes the complex needs of drug users, and, in a prison setting, the reality of penal life and culture. Harm reduction seeks to inform and empower individuals in reducing the harms associated with drug use. CSC will fail to meet this objective if it continues to stigmatize and punish drug use behind its walls. Changing the culture and attitudes of an organization that has long adopted a zero-tolerance and punitive approach to illicit drug use will take time. Establishing a PNEP explicitly recognizes that zero-tolerance does not work, nor is it possible to ensure a drug-free prison. I am reminded that it took many years for correctional culture and practice to accept Opiate Substitution Therapy (now Opioid Agonist Treatment) as a legitimate treatment and harm reduction measure. I am also reminded of the fact that opposition to supervised injection sites in the community is still widespread across Canada.

Some best practices appear to have been overlooked in the initial implementation phase of PNEP. Despite consultations with CSC's three main bargaining agents, and information sessions at select sites prior to implementation, there seems to be a lack of trust and confidence in the program, from both inmates and staff. Too much of what should be an exclusively health and harm reduction program has been shaped by security concerns. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) states that prisoners who inject drugs "should have easy and confidential access to sterile drug injecting equipment, syringes and paraphernalia." Footnote 13 This might be a hard pill to swallow for those who advocate a zero-tolerance, "war against drugs" approach. However, the fact is that a successful prison needle exchange program reduces the prevalence of communicable disease behind bars and enhances staff safety by reducing accidental needle stick injury resulting from cell and body searches. Footnote 14

The United Nations has identified the following core principles where successful PNEPs have been established elsewhere in the world:

- Support from leadership at the highest levels.

- Steadfast commitment to public health objectives, to a harm reduction approach and to the right to health of people in prison to inform and empower themselves in reducing the harms associated with injection drug use.

- Clear policy direction and oversight of the program.

- Consistent policy guidelines and protocols.

- Participation of staff and prisoners in the planning and operational process. Footnote 15

In comparing these principles against CSC's approach to date, there are some obvious learning points. Ongoing and focused attention, oversight, innovation and direction is required in light of the need to make program adjustments to ensure the highest participation rate.

- I recommend that CSC revisit its Prison Needle Exchange Program purpose and participation criteria in consultation with inmates and staff with the aim of building confidence and trust, and look to international examples in how to modify the program to enhance participation and effectiveness.

CSC Response:

Correctional Service of Canada's (CSC) Prison Needle Exchange Program (PNEP) was developed based on international examples and modified to fit the Canadian context. As mentioned in the Office of the Correctional Investigator's report, absolute anonymity cannot be guaranteed in community harm reduction program participation, and a prison environment restricts that ability even further.

CSC has gained experience managing inmates using needles in a safe and secure manner with its existing programs for EpiPens and insulin use for diabetes. A Threat Risk Assessment model, similar to the one currently in effect for EpiPens and insulin needles, has been used to determine which offenders can participate in the PNEP. Health promotion posters for the PNEP and inmate fact sheets have been developed and distributed to offenders and Frequently Asked Questions sheets for both inmates and staff have been distributed so that individuals are aware of the program, the process, and requirements for participation.

An integral piece of the PNEP implementation is the evaluation by an academic expert in harm reduction program evaluation. The evaluation includes thematic interviews with program participants and non-participants, nurses, correctional staff, and parole officers to explore issues and themes related to the program's acceptability and feasibility, including barriers to participation. Involving an independent and transparent academic will contribute to building confidence and trust from both staff and inmates. The program will continue to be developed and implemented according to scientific evidence. CSC is expecting to receive an interim report of initial findings related to concerns expressed from inmates and staff, from the academic expert, this fall.

CSC continues to engage with partners on PNEP at a national level via the National Health and Safety Policy Committee meetings, discussions with national union leadership, and comprehensive consultations at the site level as the program is rolled out across the country.

CSC is well-positioned to continue introducing harm reduction programs with the aim of reducing the harms associated with drug use in people unable or unwilling to stop. Consistent with the Government of Canada's Canadian Drug and Substances Strategy (CDSS), which includes Harm Reduction as a pillar of the response to substance misuse, the focus is on keeping people safe and minimizing harm, injury, disease or death while recognizing that the behaviour may continue despite the risks. Harm reduction keeps patients connected to healthcare, emphasizing helping patients understand their risk and the health consequences while striving to motivate patients into treatment. Harm reduction initiatives are based on a neutral-value approach to drug use and the individual.

In June 2019, CSC introduced an overdose prevention service at Drumheller Institution in the Prairie Region as another harm reduction measure available to inmates to manage their health needs.

FASD PILOT PROJECT

For this pilot project at CSC's Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC Prairies), a diagnostic team, including Health Services and the Interventions Division, aim to identify 15 to 35 offenders annually who meet the criteria for FASD and determine effective interventions to facilitate their safe transition to the community.

The goal is to develop a model that is transferable to other institutions. The initiative will also assist with responding to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada's 'Call to Action' to better address the needs of Indigenous offenders with FASD.

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) in Federal Corrections

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is a term used to describe a variety of neurodevelopmental difficulties or deficits, such as impairments to executive functioning, memory, language, visuospatial skills, and social and emotional functioning, that can occur as a result of prenatal exposure to alcohol.

Given the diagnostic challenges of identifying individuals living with FASD, there are currently no confirmed national statistics; however, according to Health Canada, the prevalence rate is estimated to be around 1% of the general Canadian population (or 9.1 for every 1,000 births). Individuals with FASD are overrepresented in the criminal justice system. While there are also no consistent national prevalence rates for FASD in correctional settings, it is estimated that 10% to 23% of federally incarcerated individuals meet the criteria for FASD. Footnote 16 Despite this high prevalence estimate and the complexities associated with assessing and diagnosing FASD in a correctional setting, Footnote 17 CSC still does not have a reliable or validated system to screen or identify this spectrum disorder at intake.

My Office has previously raised concerns regarding the lack of consistent and effective assessment and treatment practices for FASD affected offenders, and I have recommended that CSC establish an expert advisory committee that leverages community-based expertise in the development of a formal strategy for FASD in federal corrections.

While it does not appear that CSC has established a formal committee on FASD, I was pleased to hear of the creation of a toolkit to guide program delivery staff in working with offenders with FASD, and importantly, the implementation of a pilot project for FASD diagnostic and support services at the Regional Psychiatric Center (RPC).

Given the over-representation of offenders with FASD, I am looking forward to seeing the outcomes of this pilot project, and how CSC plans to implement an effective and evidence-based national strategy for FASD-affected offenders.

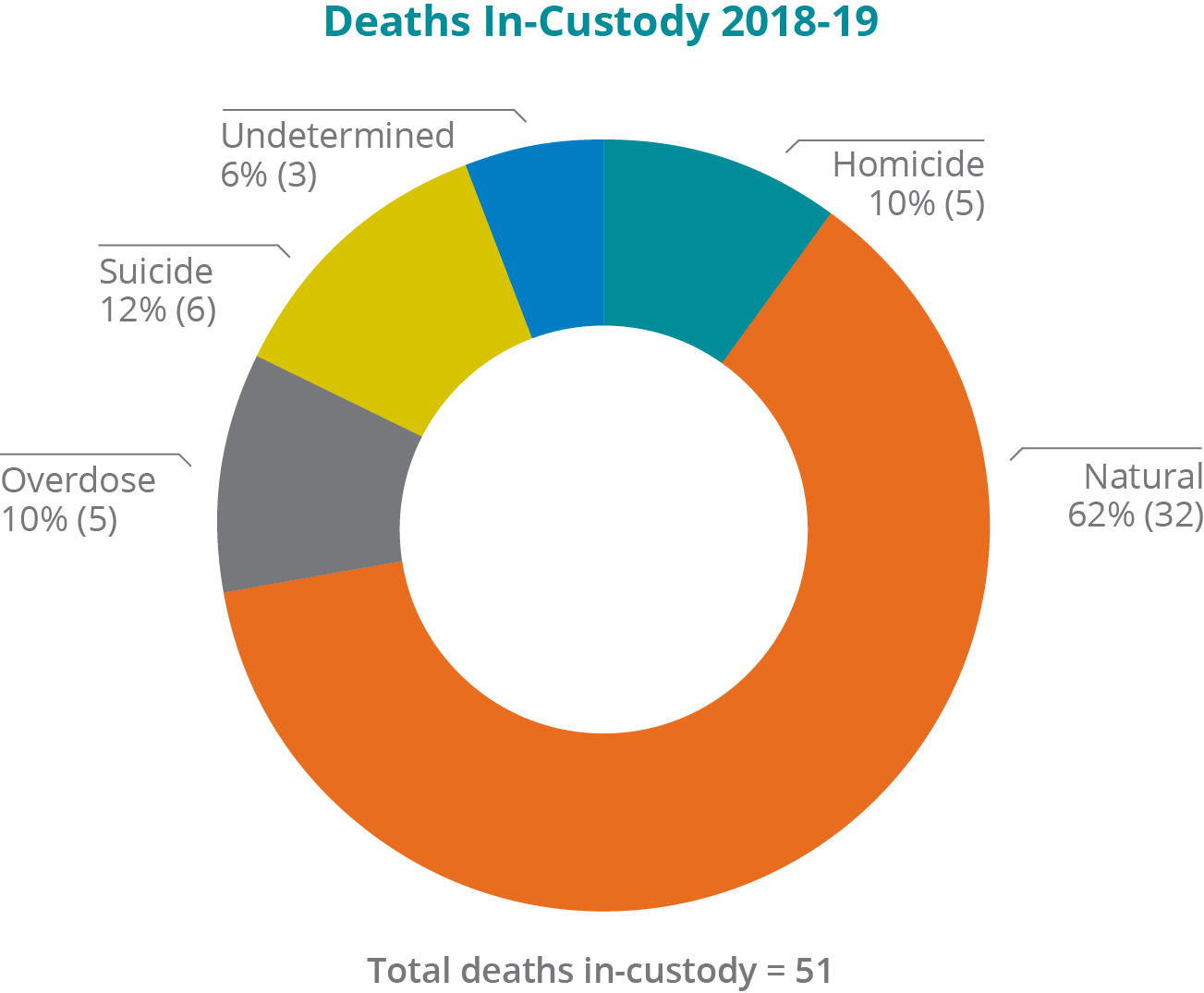

2. DEATHS IN CUSTODY

Cell - Port Cartier Institution

The number of inmate deaths in federal penitentiaries tends to fluctuate from year-to-year. There were slightly fewer in-custody deaths overall in 2018-19, primarily because there were less natural cause deaths (32 natural deaths in 2018-19 compared to 40 in 2017-18). The number of homicides in 2018-19 is concerning, the highest recorded since 2010-11 (5 homicides in 2010-11 and 2018-19). The overall number of prison suicides has generally been declining since 2014-15 and while the number of attempted suicides fell to 125 in 2018-19, it is still one of the highest numbers over the last ten years. Indigenous offenders are overrepresented in the number of suicide attempts, comprising 39% of all such incidents over the last 10 years.

Update: In the Dark

On August 2, 2016, the Office released In the Dark: An Investigation of Death in Custody Information Sharing Practices in Federal Corrections . Footnote 18 The report documented the frustration of families when information is not openly and fully shared following the death of a loved one in custody. Following the release of this report, the Service took a number of important steps to address the issues identified during the course of the Office's investigation. Positively, the Office has noted a number of improvements with respect to communication and information sharing with families including, among others:

- The establishment of a family liaison in each region responsible for being the point of contact for families.

- A modified approach to vetting and releasing information contained in National Board of Investigation reports.

- Staff training for those involved in communicating with families.

- The development of a guide for families explaining CSC policy and responsibilities following a death in custody.

Despite these positive developments, the Office has noted some slippage in the implementation of CSC's commitments following this investigation. Over the past fiscal year, the Office received a call from a lawyer of a family of a deceased inmate who indicated that the family was having difficulty accessing information following the death of their son.

After my Office intervened, it appears that the difficulty the family had in accessing information was a result of an ATIP backlog at National Headquarters. Regardless of cause or fault, as my 2016 investigation found, when families cannot get information they become frustrated and suspicious. In this case, without the correct information, the family was left wondering if a CSC staff member had been involved in their son's death. They were relieved to find out that this was not the case, but this only occurred following my Office's intervention several months after the death. Sharing information, in a timely and responsive manner, is essential to alleviating these types of feelings during a very difficult time for a family.

Cover of OCI's report titled, In the Dark:

An Investigation of Death in Custody

Information Sharing and Disclosure

Practices in Federal Corrections

The Office is also concerned that the implementation of the facilitated disclosure process, in practice, primarily involves staff providing the designated Family Liaison Coordinator with information who can then share it with the family. While this process may be appropriate and adequate for some families, others may wish to meet personally with those most closely involved in the care and custody of their loved one. This type of 'facilitated disclosure' appears to have only been used once and even then was used long after the death when information sharing had gone terribly wrong.

The Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI) offers important guidance on a sensitive disclosure process. Footnote 19 The CPSI disclosure process involves a two-stage approach where the first stage occurs as soon as reasonably possible after the event and focuses on communicating the facts that are currently available and the follow-up actions that will be taken. The second stage provides families with additional information that has resulted since the initial disclosure. Each phase of disclosure is conducted within a framework that includes the following:

- Preparation for disclosure - involves identifying those that will participate and the plan on how to proceed.

- Identifying the disclosure team - who should be present at the disclosure meeting and who will assume the lead.

- Decisions regarding what information can be disclosed and how it will be disclosed (e.g. terminology, open approach, ensuring information is understood).

- Environment for the disclosure (e.g., in person, private area, time of individual's preference).

- Review of key decisions and action items at the end of the disclosure meeting.

Moving forward, families should be offered an opportunity to meet directly with senior staff most closely involved, particularly if the family feels they are not receiving sufficient information. In recent correspondence ( Undertakings and Commitment Grid , received by the Office January 2019), the Service indicated that its commitment to develop and implement a facilitated disclosure process was complete. However, the response also indicated that the working group established to develop the process would continue to meet and refine the facilitated disclosure process. The ongoing work of this group should include consideration of the option to have more senior CSC staff members engage in direct facilitated meetings with families who wish to use such a procedure. Practices used in other fields, such as patient safety, could offer important guidance. Finally, an evaluation of the Family Liaison Coordinator role and responsibilities would provide an opportunity to assess its implementation and help shed light on ways a facilitated disclosure process, involving more senior CSC staff participating in meetings with families, could complement the role of the Family Liaison Coordinator.

Fourth Independent Review Committee (IRC) Report

In November 2018, the Fourth Independent Review Committee (IRC or Committee) released its review and report based on a sampling of 22 cases of non-natural deaths that occurred in federal custody between 2014 and 2017. Footnote 20 The Committee was largely tasked with identifying systemic issues and offering recommendations to CSC with a view to addressing non-natural deaths resulting from suicides, overdoses, and homicides. It also devoted a chapter to highlighting the case and systemic issues in the preventable death of Matthew Hines, echoing findings and recommendations made in my February 2017 Special Report to Parliament, Fatal Response: An Investigation into the Preventable Death of Matthew Ryan Hines.

In addition to their 17 recommendations, the Committee concluded their report with three key findings:

- The number of incidents involving a non-natural death in federal custody is comparatively small.

- CSC should concentrate suicide prevention and treatment efforts on subgroups of offenders who present risk factors known to be related to suicide (e.g., childhood negligence, interpersonal violence, inmates convicted of homicide of someone close to them).

- In cases where death can be linked to questionable practices by CSC staff, investigations should examine and report on issues such as the prevailing institutional culture as well as staff and inmate relations. These elements could assist in informing the development of measures that could prevent the occurrence of non-natural deaths in custody.

I concur with these findings and look forward to their incorporation into CSC's overall strategy to reduce and prevent non-natural deaths in custody.

FOURTH INDEPENDENT REVIEW COMMITTEE: SUICIDES IN FEDERAL PRISONS

- Suicide is the most common cause of non-natural deaths in custody.

- Of the 22 cases of non-natural deaths reviewed by the Committee, 12 involved suicide.

- ¾ of cases of suicide reviewed by the committee involved inmates serving sentences for homicide of a person close to them.

- While federal corrections in Canada has what is considered a low rate of suicide compared to other countries, the rate of suicide in federal prisons is still five times that of the general Canadian population (61 vs. 11.4 suicides per 100,000 people).

- Among their recommendations, the committee suggested that CSC more intentionally assess and target psychosocial and historical factors that are related to risk for suicide, and consider the impacts of prevention measures on quality of life for inmates who are considered high risk to ensure they are having a beneficial impact.

Prison Homicides and the Case of Matthew Hines

Prison infirmary - Dorchester

Penitentiary

The Committee reviewed three cases of homicide over the review period, which is representative of the average number of homicides in federal corrections each year. Further to these cases, the Committee recommended that CSC incident investigators should go beyond simply assessing adherence to policy, and their reports should more fully reflect this effort. They further suggested that internal National Board of Investigation reports should include a dedicated section to identifying areas of improper practice, policy gaps, and underlying problems that were prompted by the cases under review.

Given the circumstances, reviews and investigations surrounding the death of Matthew Hines, the Committee profiled this case separately in their report. Upon reviewing the Hines case, the Committee indicated that the Board of Investigation report and their 21 areas for improvement were "not commensurate with the totality and gravity of the findings." The Committee not only concurred with, but also quoted the findings and recommendations directly from my Fatal Response report.

Furthermore, the Committee cited the OCI investigation as a demonstration of "how an investigation into a case of this nature can lead to significant recommendations regarding accountability for what occurred as well as strategic, organizational approaches to prevent a recurrence." They further suggested that my Office's report, as well as CSC's response, should be used as a training module for CSC investigators in the future. I, too, made a similar recommendation that CSC use this case as a national teaching and training tool for all staff and management. Matthew's death has indeed prompted some substantive operational and policy changes, particularly pertaining to use of force and situation management. Though some elements of Matthew's case have been adapted into learning and training materials (e.g. Arrest and Control and Escorting, and Sudden In-Custody Death Syndrome), it is concerning that a national Lessons Learned Bulletin records this preventable death in highly euphemistic terms:

SCENARIO #1:

While inmates were returning to their cell for the stand-to-count, Correctional Officers ordered an inmate, who appeared to be acting "out of it" and behaving oddly, back to his cell for the count. They assumed he was likely intoxicated and touched the inmate's arm to gain compliance which caused the inmate to become agitated, resulting in a spontaneous use of force. This inmate, who was a large man, was cuffed from the rear and left in an awkward position. He struggled and OC spray was used several times, after which he complained he was having difficulty breathing. The inmate later died.

Best Practices in the Investigation Process and Engagement with Families

In the final component of their review, the Committee sought to identify best practices to improve investigations into deaths in custody. In doing so, the Committee suggested that the best approach for correctional agencies might be to develop their own best practices internally. Specifically, the Committee identified the need for best practices around how correctional agencies can more effectively engage and disclose information to next of kin during the investigative process. The Committee expressed support for the recommendations offered in my investigation of Matthew's death. The Committee did caution, however, that not all families have the same wishes regarding access to information following the death of a relative, and this too should be respected in the policies and procedures adopted by correctional agencies.

Aging and Dying in Prison

As part of my Office's joint investigation with the Canadian Human Rights Commission (CHRC) examining the challenges and vulnerabilities faced by older individuals in custody Aging and Dying in Prison: An Investigation into the Experiences of Older Individuals in Federal Custody (February 2019), Footnote 21 we reported that many older individuals were living out their single greatest expressed fear - dying in prison. In 2018-19, 29 offenders 50 years of age and older died of natural causes in federal custody. The results of this joint investigation are addressed later in my report; however, I want to highlight one important and relevant finding here. Prisons were never meant to house sick, palliative, or terminally ill patients, but they are increasingly being required to perform such functions.

In November 2017, CSC released its Annual Report on Deaths in Custody , which examines all deaths (natural and non-natural) in custody that occurred in a CSC institution between 2009-10 and 2015-16. Footnote 22 During this time, 254 deaths from natural causes occurred. Significantly, among those who died of natural causes, 48% had a 'Do Not Resuscitate' order on file and 50% were receiving palliative care. If we agree that prison is not an appropriate place to provide palliative or end-of-life care, the question to be asked is this: why were these individuals, whose deaths were expected, allowed to die in prison? Footnote 23

I have previously identified that criteria for granting compassionate release to a terminally ill offender are extremely restrictive. Footnote 24 Until recently, the documentation required by the Parole Board of Canada included medical evidence/rationale that end of life is not only imminent, but also certain; in some cases, the Parole Board has required medical doctors to provide a defined period of life expectancy. Such criteria make it very difficult for those in severe health decline behind bars to be released. The Parole Board, however, recently made changes to its Decision-Making Policy Manual for Parole Board Members to indicate that it is not necessary to require a defined period of life expectancy when reviewing cases for parole by exception under the "terminally ill" legislative criteria. Recent statistics from the Parole Board indicate that more releases are being made since these changes were put into effect.

Despite these efforts, far too many older terminally ill individuals are dying behind bars. As I detail later in my Annual Report, findings from the joint OCI/CHRC investigation found that many older individuals have spent decades behind bars, are institutionalized, some are now palliative, have little left to fight for and their sentences are no longer being appropriately managed. Many reported that they felt as though they have been 'forgotten,' and I would add that this occurs for many older and palliative individuals often until just days before they die. In the report, we identify two cases that were rushed through the parole system at the last minute only to have one terminally ill individual die two hours after his release to the community. While the second individual lived for nearly two months following release to a hospice, there was a fury of work to get him out before a weekend as it was thought that he only had a few days remaining. Unfortunately, these are not isolated cases.

Wheelchair that cannot fit through a

cell door - Federal Training Centre

There seems to be little purpose or value in keeping palliative individuals who pose no undue risk to public safety behind bars. CSC has committed, in its proposed policy framework, "Promoting Wellness and Independence: Older Persons in CSC Custody," to monitor the timelines and quality of each step in the process from the designation of a terminal illness to submission to the Parole Board and decision. While this is an important step, CSC and the Parole Board must work together more closely to accelerate cases of dying inmates to be prepared and heard before the Parole Board in the timeliest manner possible. In addition to this, as I argue later in my Annual Report, CSC must better utilize the information arising from its recent review and assessment of chronic health conditions in individuals in federal custody 65 years of age and older. This information is key to identifying individuals with a terminal disease who could be safely transferred from prison to the community.

Providing comprehensive health care to sick and palliative individuals is costly. CSC has established two specialized healthcare units (Assisted Living Unit at Bowden and the Psycho-Geriatric Unit at the Pacific Regional Treatment Centre) no doubt at great cost. CSC health care costs have fluctuated over the past 10 years from a low of $201 million in 2008/09 to a high of $271 million in 2012/13. While healthcare costs are impacted by many factors, the aging offender population is no doubt an important driver of rising correctional health care costs. CSC does not currently track health care costs by age so it is not known how much is spent per capita on an older person in prison for health care; however, it likely resembles the trend in Canadian society more broadly. Footnote 25 At one of the institutions visited for the investigation, three of the five beds in the institution's infirmary were taken up by older individuals who were very ill and had been there for extensive periods of time. One older individual spent eight years in the prison infirmary, and had become increasingly dependent and bed-ridden.

To improve human rights protection and cost effectiveness, my Office and the Canadian Human Rights Commission continue to call for better, safer and less expensive options in managing this older and vulnerable prison population that poses a reduced risk to public safety. A model involving medical or geriatric parole would allow individuals to apply for early release based on their age, number of years behind bars and current health status. The cost-savings of moving some of these individuals into a retirement/nursing home, or a specialized community based residential facility (halfway house) would be substantial. CSC could reallocate funds currently being used to maintain palliative individuals behind bars to pay for community placements that would be more responsive to dignity concerns.

An Update on Medical Assistance in Dying in Federal Corrections

Last year, I reported extensively on my concerns with how CSC proposed to give policy and operational effect to Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) legislation for federally sentenced terminally ill individuals. Beyond the optics of an agency of the state enabling or facilitating death behind bars, I stated in very specific and forceful terms the ethical and practical reasons for my objection to allowing MAiD to be carried out in a penitentiary setting. Despite my concerns and objections, CSC policy allows for an external provider to end the life of an inmate under "exceptional circumstances." The first such MAiD procedure was performed in a federal correctional facility during the reporting period.

The particular set of circumstances that allowed this decision to be made in this case are unclear, subject to privacy considerations and still under review by my Office. That said, though there was no advanced or formal notice given to my Office, I have no reason to doubt that the actual MAiD procedure was carried out professionally and compassionately. My review will be focused more on how and when CSC and Parole Board decision-makers got to the point that there was no other safer or more humane alternative to ending life than in a federal prison.

In the meantime, as my Office carries out a review of this case, I encourage the Parole Board of Canada and the Correctional Service to conduct a joint review of the eligibility and procedural criteria that gives effect to Section 121 "compassionate release" provisions of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act . This review would focus on ensuring decision-making in cases of terminal illness is fully compliant with the spirit and intent of MAiD legislation. I am suggesting that there is a fundamental conflict of law or procedure between MAiD and the current interpretation and application of Section 121 criteria. Such a review would be carried out mindful of the need for a terminally ill person still under federal sentence to be allowed to make the decision to hasten the end of their life in the community, in a manner, setting and timing that respects personal autonomy and informed choice.

- I recommend that the Correctional Service of Canada, in consultation with the Parole Board of Canada, conduct a joint review of the application of Section 121 "compassionate release" provisions of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act to ensure policy and procedure is consistent with the spirit and intent of Medical Assistance in Dying legislation.

CSC Response:

Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) is continuing to collaborate with the Parole Board Canada (PBC) in reviewing the application of Parole by Exception under Section 121 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act.

Most recently, on June 3, 2019, CSC, in partnership with PBC, released its poster and fact sheets for offenders and staff in order to increase awareness about Parole by Exception. These communication materials have been disseminated to all institutions for sharing with staff and offenders.

In July 2018, CSC issued direction to staff to promptly notify the Institutional Parole Officer (IPO) so that all release options - including Parole by Exception under Section 121 - may be considered when an inmate is determined to be terminally ill and/or eligible for Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD). As a result, staff are able to track the progress of each case from the moment health services staff notifies the parole officer up to the time the decision has been made by the PBC to grant or deny Parole by Exception.

CSC in collaboration with the PBC, will continue its efforts in improving results in terms of proactive and collaborative case management for terminally ill offenders.

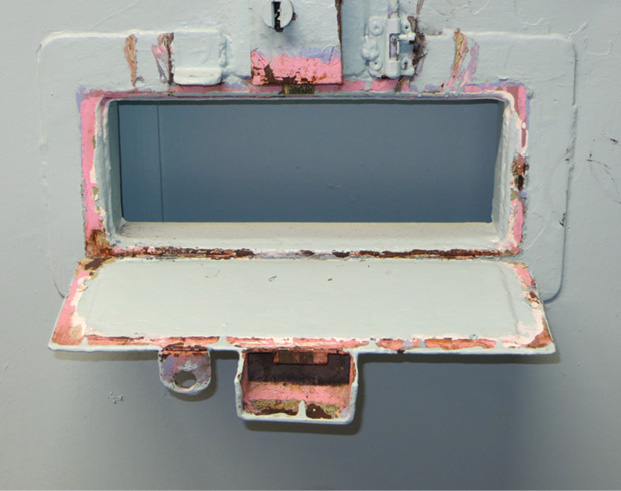

3. CONDITIONS OF CONFINEMENT

Food slot - Millhaven Institution

The Service shall take all reasonable steps to ensure that penitentiaries, the penitentiary environment, the living and working conditions of inmates and the working conditions of staff members are safe, healthful and free of practices that undermine a person's sense of personal dignity.

(Section 70, Corrections and Conditional Release Act)

"Staff embody, in prisoners' eyes, the regime of a prison, and its fairness." Footnote 26

This chapter features three case studies - Dysfunction at Edmonton Institution, Use of Force at Atlantic Institution and Prison Food. The issues raised, while derived from individual investigations, have systemic roots. Each case study brings forward findings and lessons that reach beyond the particular institution or issue under review. Collectively, they speak to organizational "culture" - the patterns of beliefs, assumptions, norms, codes of conduct, and ways of thinking and doing that define how an organization acts and behaves. Fixing problematic elements of CSC's organizational culture is not within my mandate. However, when unprofessional conduct, toxicity, resistance or other dysfunction in the workplace create adverse effects for the inmate population, as I found in the Edmonton and Atlantic Institution examples, I have a duty and responsibility to report and act upon it. The third case study on prison food speaks to another part of CSC's corporate culture, one that is fixated on compliance to the exclusion and detriment of other objectives, such as the safety, health and well-being of inmates.

Case Study 1: Dysfunction at Edmonton Institution

It is no secret that Edmonton Institution, a maximum-security facility, has been plagued by a toxic and troubled workplace culture where dysfunction, abuse of power, and harassment have festered for years. In my last Annual Report, I warned that a toxic workplace environment can lead to an abuse of power and mistreatment:

The lesson to emerge from maximum security Edmonton Institution this past year is that staff practices that undermine or degrade human dignity - sexual harassment, bullying, discrimination - can lead to a toxic work culture. A workplace that runs on fear, reprisal and intimidation is highly dysfunctional; it is the antithesis of modeling appropriate offender behaviour. | (I)f staff disrespect, humiliate or disabuse each other one can only imagine how they might treat prisoners. I have no power or authority to investigate labour relations issues, but when staff actions or misbehaviour negatively impacts offenders it is perfectly within my remit to take appropriate action. Footnote 27

My Office was first seized with the situation at Edmonton Institution in December 2016. At that time, my predecessor referred to Edmonton Institution as "dysfunctional," a facility where a "toxic workplace culture leads to policy violations, unfair treatment of offenders and potential human rights abuses." The independent human resource consultants brought in to report on these matters, and to respond to a recommendation made by my Office, described an institution that was lawless, toxic and callous, a workplace environment in which "a culture of fear, mistrust, intimidation, disorganization and inconsistency" prevails. Footnote 28 It was especially disturbing to find that the external report contains allegations that employees used lockdowns, searches and safety complaints to "rile up inmates, to shirk their responsibilities, or to get back at management." Footnote 29 The staff behaviours described in the consultant report do not happen outside of an organizational culture that allows it to happen.

EDMONTON INSTITUTION NEEDS ASSESSMENT AND ANALYSIS

An internal employee survey, released in January 2019, identifies the extent of challenges in creating a safe and respectful workplace at Edmonton Institution:

- 96% of employees reported they had experienced conflict in the workplace. The majority said conflict ruined their working relationship and destroyed trust with staff.

- 17 current employees say they have been sexually assaulted by a co-worker. 65 respondents (23%) reported being sexually harassed by a co-worker.

- 60% have encountered abuse of power within the workplace.

- Over half of respondents said they worked in a "culture of fear." Most said that fear did not come from interactions with inmates but rather co-workers.

- 51% believe that a "culture of fear" contributes to divisions between work groups (e.g., security vs. programs staff). The majority believe workplace fear allows certain work groups to control the workplace.

- Over 60% of employees had experienced violence in the workplace. Most common forms of workplace violence: threatening behaviour (23%); verbal abuse (22%); verbal intimidation (22%). 11% had witnessed co-worker violence on inmates.

- More than two-thirds of respondents have witnessed harassing behaviour in the workplace.

Source: Families First: Supports for Occupational Stress Inc. (January 2019). Edmonton Institution Needs Assessment

Despite personal interventions by the Minister, the previous and current Commissioners of Corrections to get to the underlying causes of staff misconduct at this troubled institution, the workplace culture remains highly problematic. A recent (January 2019) follow-up workplace needs assessment provides a comparative analysis of historic and current levels of internal workplace strife, conflict and dysfunction at Edmonton Institution. Footnote 30

In a prison setting, staff set expectations of how order, safety and authority is perceived and exercised. It is instructive that the needs assessment of current employees indicated that they feared one another more than they did inmates. Over 60% of employees had experienced violence in the workplace. More than one-quarter reported observing managers or supervisors threatening other staff with physical violence. Just as disturbing, it seems that professional misconduct is rarely reported up to management out of fear of being labelled a "rat," fear of retaliation or other violations of the "code."

It is encouraging that the needs assessment notes some areas of progress and positive momentum for change compared to the situation a few years ago. Nevertheless, as I document more fully below, a culture of impunity still seems firmly rooted at Edmonton Institution; it is more than just a case of a few bad apples or isolated incidents. The Service continues to face several lawsuits and ongoing allegations of harassment, abuse of power, neglect and intimidation from current and former Edmonton Institution employees as well as inmates. A series of administrative reviews and criminal investigations of staff wrongdoing have culminated in the dismissal or suspension of several staff members. New leadership at the regional and institutional levels has not yet fully rooted out the remaining vestiges of unprofessional behaviour. One recent media report describes Edmonton Institution as "rotten." Footnote 31 Several advocates have called for a public inquiry to address the underlying malfeasance.

As has been made clear previously, a dysfunctional and abusive workplace culture has spill-over or contagion effects that can put the safety of inmates in jeopardy. As shared with the Commissioner, my findings from an incident documented on video suggest staff knowledge, possibly even complicity, in a repeated series of inmate-on-inmate assaults that occurred on Unit 5 at Edmonton Institution from August to October 2018. I am publicly releasing the findings and implications of my investigation because I believe Canadians have a right to know how the Service intends to fix elements of a workplace and inmate culture that perpetrates, condones or otherwise gives license to violence, abusive behaviour and mistreatment.

In late August 2018, the OCI Senior Investigator assigned to Edmonton Institution met with a number of protected status inmates who alleged that inmates on other ranges on the main living unit were throwing food items, liquids and other objects at them during movement. These incidents were under video surveillance and observation by staff located in the Unit's sub-control area. Officers assigned to the Unit refused to staff the direct observation post/desk, which is open to the Unit's four ranges, because of safety concerns and out of fear of being hit by thrown items. During his debrief, the allegations made by the victimized inmates and safety concerns of the Senior Investigator were shared with senior management. My investigator was given clear indication from management that the physical assaults were known to them, that they had been reported before and that dynamic security was a challenge on that particular Unit. Moreover, at the debrief meeting, corrective measures were discussed, including possibly moving protected status inmates next to the Unit's exit, thus potentially avoiding taunts, insults and incitement to violence during movement.

During a return visit to Edmonton Institution, which occurred at the end of October, the Senior Investigator learned that the situation from August had not measurably improved. Protected status inmates were still subjected to assaultive and intimidating behaviour and officers were still not providing physical escort, direct observation or intervening to stop the assailants. In fact, by October, the violence seemed to have escalated, and had become a well-organized and recurrent affair. Video evidence of the October 25, 2018 incident clearly shows inmates from the instigating ranges taking their time to plan and prepare for the assault. They can be seen looking for and gathering food and other items, heating up food in the microwave, carefully watching and waiting until staff members had moved out of the way to begin their assault as protected status inmates walked by the range barriers without staff escort. After the incident, some of the assailants can be seen celebrating and congratulating one another, acts that are reprehensible in and of themselves.

In context of an incident that appears to have been repeated a number of times, and with knowledge that protected status inmates were about to be moved, officers could not have missed the preparations that were underway in the ranges that housed the assailants. The video recordings also demonstrate Correctional Officers in the Unit's main entrance handling waste while inmates are assaulted, under direct surveillance, as they move towards the main entrance. The video evidence shows Edmonton Institution failed to appropriately monitor and safely control inmate movement, in a facility where all population movements are highly regulated.

That these incidents continued to occur even though Senior Management was made aware of them months before is extremely disturbing. The repeated and orchestrated nature of these incidents suggests those committing them did so with relative impunity. Had these assaults been directed at staff, the outcome would surely have been very different. As it turned out, the corrective measures discussed in August - ensuring correctional officers and management were present for all range movement on the Unit in question - were only put in place after the Senior Investigator had completed his return visit at the end of October, and only after video evidence of these incidents had been disclosed to the Commissioner via my correspondence of November 9, 2018. In other words, these incidents were not reported up or through CSC's regional or national chains, nor was corrective action taken, until the disclosure made to the Commissioner.

Twenty four inmates were institutionally charged for assaulting other inmates in the incident in question. Footnote 32 By refusing to provide proper escort and protection, by not intervening to stop the assaults before or after the fact, and through other acts of omission and commission, it appears that staff and management of Edmonton Institution colluded in behaviour that anywhere else would be considered offensive, possibly even criminal. CSC failed in its statutory obligation to intervene to protect a vulnerable sub-population that had knowingly and repeatedly been subjected to assaultive, degrading and humiliating behaviour. No human being, regardless of their status or crime, deserves to be treated in such a cruel and unusual manner.

CSC staff walking ahead of the inmates who were

later assaulted - Edmonton Institution.

In light of these incidents, and in context of an occupational culture that continues to create an adversarial environment for offenders, I issued the following recommendations:

- I recommend immediate steps be taken to ensure the safety, dignity and security of 'protected' status inmates at Edmonton Institution and that a full written debrief is provided to my Office by November 16, 2018 addressing the following measures:

- Increased staff presence, enhanced dynamic security and staffing of direct observation posts on Unit 5.

- Provision of close protective security escorts during movements involving protected status individuals and groups on Unit 5 until safer alternatives can be implemented.

- Direct management presence and oversight of Unit 5 personnel.

- Population management provisions and protocols that significantly reduce the risk of violence being perpetrated against vulnerable or protected status inmates.

- I recommend that you immediately convene a Section 20 investigation into all assaults against protected status inmates that occurred between August 2018 and October 25, 2018.

- This investigation should be chaired by an independent and credible person with recognized legal expertise in prison human rights.

- The Board's report and CSC management action plan, signed by you, should be released publicly and no later than February 15, 2019.

- Concurrently, as an accountability measure, I request that all disciplinary charges, reports or proceedings taken against inmates or staff for their involvement, either implied or direct, in these incidents be shared with my Office.