Final Report

October 22, 2012

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Parliament's Intent for Sections 81 and 84

Use of Section 81 Agreements – Analysis

Barriers in Developing and Maintaining Section 81 Agreements

Barriers in the Aboriginal Community

Use of Section 84 Releases – Analysis

CSC 's Continuum of Care Model for Aboriginal Corrections

Implementation of Gladue Principles in Federal Corrections

Appendix A – Consultations and Interviews

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Corrections and Conditional Release Act ( CCRA ) makes specific reference to the unique needs and circumstances of Aboriginal Canadians in federal corrections. The Act provides for special provisions (Sections 81 and 84), which are intended to ameliorate over-representation of Aboriginal people in federal penitentiaries and address long-standing differential outcomes for Aboriginal offenders.

- It has been 20 years since the CCRA came into force, and the Office of the Correctional Investigator ( OCI ) believes that a systematic investigation of Sections 81 and 84 of the Act is both timely and important. This investigation aims to determine the extent to which the Correctional Service of Canada ( CSC ) has fulfilled Parliament's intent at the time that the CCRA came into force. It examines the status and use of Section 81 and 84 provisions in federal corrections for the period ending March 2012, identifies some best practices in Aboriginal corrections and assesses the commitment by CSC to adopt principles set out in the Supreme Court of Canada's landmark decision of R. v. Gladue . The investigation concludes with key recommendations for enhancing CSC 's capacity and compliance with Sections 81 and 84 of the CCRA .

- Section 81 of the CCRA was intended to give CSC the capacity to enter into agreements with Aboriginal communities for the care and custody of offenders who would otherwise be held in a CSC facility. It was conceived to enable a degree of Aboriginal control, or at least participation in, an offender's sentence, from the point of sentencing to warrant expiry. Section 81 further allows Aboriginal communities to have a key role in delivering programs within correctional institutions and to those offenders accepted under a Section 81 agreement (Aboriginal Healing Lodges or Healing Centres).

- The investigation found that, as of March 2012, there were only 68 Section 81 bed spaces in Canada and no Section 81 agreements in British Columbia, Ontario, and Atlantic Canada or in the North. Until September 2011, there were no Section 81 Healing Lodge spaces available for Aboriginal women.

- One of the major factors that inhibit existing Section 81 Healing Lodges from operating at full capacity and new Healing Lodges from being developed is the requirement that they limit their intake to minimum security offenders or, in rare cases, to "low risk" medium security offenders. The evolution of this policy, which was neither Parliament's intent nor CSC 's original vision, is seen as a way for the Service to minimize risk and exposure. It creates a number of problems, exacerbated by the fact that only 11.3% of Aboriginal male offenders, or 337 individuals,were housed in minimum-security institutions in 2010-2011. In effect, CSC policy excludes almost 90% of incarcerated Aboriginal offenders from even being considered for transfer to a Healing Lodge. With this limitation, it is no surprise that the investigation found that Healing Lodges do not operate at full capacity.

- In addition to the four Section 81 Healing Lodges, CSC has established four Healing Lodges operated as CSC minimum-security institutions (with the exception of the Healing Lodge for women that accepts both minimum and some medium security inmates). CSC -operated Healing Lodges can provide accommodation for up to 194 federal incarcerated offenders, which include 44 beds for Aboriginal women.

- Section 81 Healing Lodges operate on five-year contribution agreement cycles and enjoy no sense of permanency. There is no guarantee that the agreements will be renewed. Indeed, they are subject to changes in CSC priorities and funding, including a 2001 reallocation of $11.6M earmarked for new Section 81 facilities to other requirements.

- We found that the discrepancy in funding between Section 81 Healing Lodges and those operated by CSC is substantial. In 2009-2010, the allocation of funding to the four CSC - operated Healing Lodges totalled $21,555,037, while the amount allocated to Section 81 Healing Lodges was just $4,819,479. Chronic under-funding of Section 81 Healing Lodges means that they are unable to provide comparable CSC wages or unionized job security. As a result, many Healing Lodge staff seek employment with CSC , where salaries can be 50% higher for similar work. It is estimated that it costs approximately $34,000 to train a Healing Lodge employee to CSC requirements, but the Lodge operators receive no recognition or compensation for that expense.

- Another factor inhibiting the success and expansion of Section 81 Healing Lodges has been community acceptance. Just as in many non-Aboriginal communities, not every Aboriginal community is willing to have offenders housed in their midst or take on the responsibility for their management.

- CSC did not originally intend to operate its Healing Lodges in competition with Section 81 facilities, but rather saw itself as providing an intermediate step that would ultimately result in the transfer of those facilities to community control under Section 81. As the investigation notes, however, negotiations to facilitate transfer of CSC Healing Lodges to First Nation control appear to have been abandoned. Most negotiations never moved beyond preliminary stages. In some Aboriginal communities, this breakdown in engagement has resulted in long-standing acrimony and mistrust directed at Canada's correctional authority.

- The intent of Section 84 was to enhance the information provided to the Parole Board of Canada and to enable Aboriginal communities to propose conditions for offenders wanting to be released into their communities. It was not intended to be a lengthy or onerous process, yet that is exactly what it has become: cumbersome, time-consuming and misunderstood. A successful Section 84 release plan requires significant time-sensitive and co-ordinated action. As the investigation reveals, there are only 12 Aboriginal Community Development Officers across Canada responsible for bridging the interests of the offender and the community prior to release.

- The Supreme Court of Canada in R. v. Gladue (1995) and, more recently, in a March 2012 decision ( R. v. Ipeelee ) compelled judges to use a different method of analysis in determining a suitable sentence for Aboriginal offenders by paying particular attention to the unique circumstances of Aboriginal people and their social histories. These are commonly referred to as Gladue principles or factors. CSC has incorporated Gladue principles in its policy framework, requiring it to consider Aboriginal social history when making decisions affecting the retained rights and liberties of Aboriginal offenders. Although the Gladue decision refers to sentencing considerations, it is reasonable to conclude that Section 81 facilities would be consistent with the Supreme Court's view of providing a culturally appropriate option for federally sentenced Aboriginal people. Notwithstanding, we find that Gladue principles are not well-understood within CSC and are unevenly applied.

- Today, 21% of the federal inmate population claims Aboriginal ancestry. The gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal offenders continues to widen on nearly every indicator of correctional performance:

- Aboriginal offenders serve disproportionately more of their sentence behind bars before first release.

- Aboriginal offenders are under-represented in community supervision populations and over-represented in maximum security institutions.

- Aboriginal offenders are more likely to return to prison on revocation of parole.

- Aboriginal offenders are disproportionately involved in institutional security incidents, use of force interventions, segregation placements and self-injurious behaviour.

The investigation found a number of barriers in CSC 's implementation of Sections 81 and 84. These barriers inadvertently perpetuate conditions that further disadvantage and/or discriminate against Aboriginal offenders in federal corrections, leading to differential outcomes:

- Restricted access to Section 81 facilities and opportunities outside CSC 's Prairie and Quebec regions.

- Under-resourcing and temporary funding arrangements for Aboriginal-controlled Healing Lodges leading to financial insecurity and lack of permanency.

- Significant differences in salaries and working conditions between facilities owned and operated by CSC versus Section 81 arrangements.

- Restricted eligibility criteria that effectively exclude most Aboriginal offenders from consideration of placement in a Section 81 Healing Lodge.

- Unreasonably delayed development and implementation of specific policy supports and standards to negotiate and establish an operational framework to support robust, timely and coordinated implementation of Section 81 and 84 arrangements.

- Limited understanding and awareness within CSC of Aboriginal peoples, cultures, spirituality and approaches to healing.

- Limited understanding and inadequate consideration and application of Gladue factors in correctional decision-making affecting the interests of Aboriginal offenders.

- Funding and contractual limitations imposed by CSC that impede Elders from providing quality support, guidance and ceremony and placing the Service's Continuum of Care Model for Aboriginal offenders in jeopardy.

- Inadequate response to the urban reality and demographics of Aboriginal offenders, most of whom will not return to a traditional First Nations reserve.

- CSC 's senior management table lacks a Deputy Commissioner with focused and singular responsibility for progress in Aboriginal Corrections.

The OCI concludes that CSC has not met Parliament's intent with respect to provisions set out in Sections 81 and 84 of the CCRA . CSC has not fully or sufficiently committed itself to implementing key legal provisions intended to address systemic disadvantage.

- It is understood that CSC does not control who is sent to prison by the courts. However, 20 years after enactment of the CCRA , the CSC has failed to make the kind of systemic, policy and resource changes that are required in law to address factors within its control that would help mitigate the chronic over-representation of Aboriginal people in federal penitentiaries.

SCOPE OF INVESTIGATION

1. It has been 20 years since the Corrections and Conditional Release Act ( CCRA )(S.C. 1992, c. 20) came into force on June 18, 1992, and 13 years since the Supreme Court of Canada's landmark decision in R. v. Gladue . [1] Twenty years later, the Office of the Correctional Investigator ( OCI ) believes that it is both timely and important to review Aboriginal-specific sections of the CCRA . This investigation aims to determine the extent to which the Correctional Service of Canada ( CSC ) has reflected Parliament's intent at the time that the CCRA came into force. It examines the status and use of Section 81 and 84 provisions up to the period ending March 2012, identifies some best practices in Aboriginal corrections and assesses the commitment by CSC to adopt the principles set out in R. v. Gladue . The investigation concludes with key findings and recommendations for enhancing CSC 's capacity and compliance with Section 81 and 84 provisions of the CCRA .

METHODOLOGY

2. The Correctional Service was notified of the OCI 's intent to commence this investigation in October 2011. In the course of this investigation, a review of CSC , Public Safety Canada, Parliamentary Committee reports and other relevant documentation was completed. The documents consulted are listed in Appendix B . CSC Headquarters provided all available and relevant documents and statistics relating to Sections 81 and 84. All data and sources are accurate as of March 31, 2012. A review copy of this report was shared with CSC headquarters for factual verification on August 31, 2012.

3. In conducting the investigation, three of the four existing Section 81 Healing Lodges were visited: Stan Daniels Healing Centre in Alberta; Prince Albert Grand Council Spiritual Healing Lodge in Saskatchewan; and Waseskun Healing Centre in Quebec. A site visit of the newly opened Buffalo Sage Healing Centre for women in Alberta was also conducted. The fourth Lodge, O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi, located in a remote part of Manitoba, was not visited due to travel time and funding restrictions.

4. Interviews were held with CSC Headquarters staff and regional officials in the Pacific and Prairies regions. Site visits were conducted at three of the four CSC -operated Healing Lodges: Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge for women in Saskatchewan; Pe Sakastew Centre in Alberta; and Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village in British Columbia. (Willow Cree Healing Lodge in Saskatchewan was not visited because of time limitations.) Interviews were also conducted with staff from the Native Counselling Services of Alberta (which operates both the Stan Daniels Healing Centre and the Buffalo Sage Healing Centre); Elders at Saskatchewan Penitentiary (where an Aboriginal Pathways Unit has been established); an Elder at Pe Sakastew Centre in Alberta; and leadership from the Nekaneet First Nation (where the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge is located).

5. To gain better insight into the original intent of Sections 81 and 84, the investigation was enhanced through correspondence with a member of the 1980s Correctional Law Review and a former Director of CSC 's Aboriginal Issues Branch. Supplementary information used for this investigation was also provided by the Aboriginal Corrections Policy Division, Public Safety Canada. A list of all site visits and consultations, with the exception of individuals who spoke under condition of confidentiality, is attached as Appendix A .

PARLIAMENT'S INTENT FOR SECTIONS 81 AND 84

6. The CCRA was enacted with the express purpose of contributing to the maintenance of a just, peaceful and safe society by: (a) carrying out sentences imposed by courts through the safe and humane custody and supervision of offenders; and, (b) assisting the rehabilitation of offenders and their reintegration into the community as law-abiding citizens through the provision of programs in penitentiaries and in the community. The principles guiding the CCRA during the period covered by this investigation include: (a) the protection of society be the paramount consideration in the corrections process; (b) the Correctional Service of Canada use the least restrictive measures consistent with the protection of the public, staff members and offenders; and (c) correctional policies, programs and practices respect gender, ethnic, cultural and linguistic differences and be responsive to the special needs of women and Aboriginal peoples, as well as to the needs of other groups of offenders with special requirements. [2]

7. With respect to Aboriginal offenders, the CCRA includes specific provisions relating to their care, custody and release:

81. (1) The Minister, or a person authorized by the Minister, may enter into an agreement with an aboriginal community for the provision of correctional services to aboriginal offenders and for payment by the Minister, or by a person authorized by the Minister, in respect of the provision of those services.

(2) Notwithstanding subsection (1), an agreement entered into under that subsection may provide for the provision of correctional services to a non-aboriginal offender.

(3) In accordance with any agreement entered into under subsection (1), the Commissioner may transfer an offender to the care and custody of an aboriginal community, with the consent of the offender and of the aboriginal community.

84. Where an inmate who is applying for parole has expressed an interest in being released to an aboriginal community, the Service shall, if the inmate consents, give the aboriginal community

( a ) adequate notice of the inmate's parole application; and

( b ) an opportunity to propose a plan for the inmate's release to, and integration into, the aboriginal community.

84.1 Where an offender who is required to be supervised by a long-term supervision order has expressed an interest in being supervised in an aboriginal community, the Service shall, if the offender consents, give the aboriginal community

( a ) adequate notice of the order; and

( b ) an opportunity to propose a plan for the offender's release on supervision, and integration, into the aboriginal community.

8. Aboriginal-specific provisions of the CCRA are a natural and progressive extension of section 35 of the Canadian Constitution respecting existing treaty rights of Aboriginal peoples in Canada and their unique traditions, customs and cultures, as well as section 25 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The CCRA provisions for Aboriginal offenders in fact arise from years of federal task forces and commissions, as well as previous attempts to involve Aboriginal people in developing and delivering programs and services to Aboriginal offenders in correctional institutions and in the community. Prior to the enactment of the CCRA , Aboriginal communities and organizations were instrumental in establishing Native Brotherhoods and Sisterhoods in federal correctional institutions, as well as co-ordinating Elders' services, substance abuse programs and cultural activities for incarcerated Aboriginal people.

9. Other sections of the CCRA are also relevant to this investigation. These include: section 80, which directs CSC to provide programs designed to address the needs of Aboriginal offenders; section 82, which establishes a consultative body, the National Aboriginal Advisory Committee; and section 83, which makes it clear that "aboriginal spirituality and aboriginal spiritual leaders and elders have the same status as other religions and other religious leaders." An earlier OCI report (November 2009), entitled Good Intentions, Disappointing Results: A Progress Report on Federal Aboriginal Corrections, examined many of these issues in detail. [3]

Section 81

10. Section 81 of the Act is to be given the widest possible interpretation when both sub-sections (1) and (3) are read together. It gives Aboriginal communities and organizations the latitude to negotiate whether they want to enter into an agreement, the number and type of offenders they are prepared to accept and the risk they will take in accepting offenders into their communities. This section of the CCRA was drafted in such a way as to enable a degree of Aboriginal community control, or at the very least, participation in an offender's sentence, from the point of sentencing to warrant expiry.

11. This provision does not place express limitations on the offender's security level that an Aboriginal community could not accept, nor the time during which an Aboriginal offender would be under the authority of an Aboriginal community or organization. In fact, CSC initially felt that Section 81 arrangements would eventually be available to all Aboriginal inmates regardless of security classification, although it was recognized that it would take time to build trust between CSC and Aboriginal communities. [4]

12. Significantly, the section further allows for Aboriginal people to play a key role in delivering programs within institutions and does not exclude non-Aboriginal offenders from being accepted under a Section 81 agreement. Section 81 is purposefully broad to: provide options for care and custody to the broadest number of Aboriginal inmates (First Nations, Métis and Inuit) in federal institutions in order to eventually reduce over-representation; provide appropriate programs and services to Aboriginal offenders based on traditional spiritual and cultural values; and reinforce relationships with Aboriginal communities.

13. It is important to understand that Section 81 does not transfer jurisdictional responsibility for corrections, which remains with the Federal Government. Rather, it is permissive legislation that allows for certain services and programming, including care and custody, to be negotiated and delivered by Aboriginal people and communities for payment by the Crown. This distinction between transfer of correctional services to Aboriginal communities and jurisdictional control (which remains the prerogative of the Federal Government) has been made clear from the onset through statements by the Solicitor General (now Minister of Public Safety) during parliamentary hearings, [5] court action [6] and, subsequently, by the federal Inherent Right of Self-Government Policy . [7] As they have evolved, Section 81 agreements rely on mutual consent, trust and recognition between two respective orders of government.

Section 84

14. Section 84 of the CCRA was intended, in part, as a response to long-standing criticisms of the Canadian correctional system by Aboriginal communities and organizations. Consultations as part of the 1988 Task Force on Aboriginal People in Federal Corrections, among others, heard that offenders were being released into communities without notice, without communities knowing what had happened to the offender while incarcerated and without the ability to propose conditions that the community felt were important to ensure its safety. As a result, Aboriginal communities were not able to present a plan to support the successful release and reintegration of the offender or to have the ability to hold an offender accountable to that plan.

15. The original intent of Section 84 was to enhance the information provided to the National Parole Board (now Parole Board of Canada) and to give authority and voice to Aboriginal communities in preparing a release plan. It was not intended to trigger a lengthy or onerous process for CSC , the offender or the community.

16. Section 84 was originally conceived within the context and confines of First Nation and Inuit communities, which have defined leadership and geographic boundaries. It was recognized, however, that Section 84 also had to apply to those offenders being released to urban areas due to the fact that the majority of Aboriginal offenders come from, and are released to, urban areas. It was further acknowledged that this emerging urban reality would present significant challenges, particularly in the larger metropolitan centres, and that those protocols and processes would have to evolve over time and through experimentation and adaptation.

CONTEXT AND BACKGROUND

17. The severe and chronic state of Aboriginal over-representation in federal penitentiaries has been a concern of CSC , and the Federal Government since the 1970s. Aboriginal offenders now account for 21.5% of CSC 's incarcerated population and 13.6% of offenders supervised in the community. The total Aboriginal offender population (community and institutional) represents 18.5% of all federal offenders. [8] The situation of Aboriginal female offenders is even more concerning. In 2010-11, Aboriginal women accounted for over 31.9% of all federally incarcerated women, [9] representing an increase of 85.7% over the last decade. [10]

18. While Aboriginal people are over-represented in federal corrections nationally, the numbers reach even more critical levels in the Prairie Region, where Aboriginal people comprise more than 55% of the total inmate population at the Saskatchewan Penitentiary and more than 60% at Stony Mountain Penitentiary. The situation is even worse in some provincial institutions. For example, in 2005 Aboriginal people in Saskatchewan represented 14.9% of the total population but accounted for 81% of those admitted to provincial custody and 76% of youth admitted to custody. Estimates at that time indicated that the national adult Aboriginal incarceration rate, both federally and provincially, was 910 per 100,000 as compared to 109 per 100,000 for non-Aboriginal Canadians. [11]

19. The Aboriginal population is much younger and growing much faster compared with the rest of the Canadian population. [12] As a consequence, there are proportionally more Aboriginal people either in or about to enter "at risk" of conflict with the law age groups (18 to 25-year-old men and women). It is anticipated that the current Aboriginal "baby boom" will cause the number of Aboriginal offenders to rise even further over time. For example, according to Statistics Canada population projections for Saskatchewan, by 2017 the proportion of Aboriginal young adults in that province is expected to double from 17% in 2001 to 30% in 2017. [13] This growing cohort of Aboriginal youth is already a key and independent driver in rising provincial and federal rates of incarceration.

20. Up until the 1960s, it is generally acknowledged that Aboriginal people were, in fact, under-represented in federal penitentiaries. That changed over the following years and was finally recognized by the Federal Government in a 1975 report by the Treasury Board Secretariat, [14] which noted that the Aboriginal inmate population in federal penitentiaries was 8% over-represented in institutions in proportion to their population in Canada. [15]

21. In February 1975, a National Conference on Native Peoples and the Criminal Justice System and a Federal-Provincial Meeting of Ministers were held in Edmonton, Alberta. These events made clear that: Aboriginal offenders faced unwarranted detention in maximum security facilities; it was virtually impossible for them to transfer to lower security penitentiaries; and there was a need for greater involvement of Aboriginal communities and organizations in corrections. [16] As a result, the Federal-Provincial Meeting of Ministers adopted the general principle that Aboriginal communities should have greater responsibility for the delivery of criminal justice services to their people. [17]

22. Following the Edmonton Conference, several federal and provincial task forces affirmed the need for greater Aboriginal participation, responsibility and control over corrections. In 1988, the Task Force on Aboriginal Peoples in Federal Corrections [18] recommended the adoption of the Correctional Law Review's proposal to create special legislative provisions that would allow Aboriginal people to assume greater control over corrections.

23. In 1991, the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry of Manitoba went further and concluded that the principles and procedures of the Canadian criminal justice system were incompatible with Aboriginal custom and law. [19] The Inquiry recommended that Aboriginal communities be empowered to establish a separate, Aboriginal-controlled justice system. [20] That same year, the Law Reform Commission of Canada stated that the justice system should not be a uniform system, but one which Aboriginal people themselves have shaped and moulded to their particular needs and that there should be community-based and controlled correctional facilities. [21]

24. Arguably, the most important review of Canada's relationship with Aboriginal people was undertaken by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal People (RCAP). In its 1995 interim report, Bridging the Cultural Divide , the Commission concluded that "the justice system has failed Aboriginal peoples" and the key indicator demonstrating this failure is the steadily increasing over-representation of Aboriginal people in Canadian penitentiaries and prisons. [22] The Commission report recognized the value of Aboriginal cultural and spiritual programs and affirmed the intent of the CCRA to ensure their equality in the federal institutions. RCAP also recognized the need for "community-based and community-controlled Aboriginal programs that build upon the work done inside the prisons."

25. The findings from various task forces and commissions all point to the failure to adapt correctional systems to meet the needs of the growing Aboriginal offender population. While some remedial action had taken place in other parts of the justice system, most noticeably through the improvement of policing by First Nations and through the expansion of circuit courts and Aboriginal courts in both urban and First Nation communities, the prevailing view is that the justice system has failed Aboriginal people. This viewpoint can be traced directly to the chronic and increasing over-representation of Aboriginal people in provincial, territorial and federal correctional facilities. As Aboriginal over-representation increased over the past decades, Aboriginal political leaders and the media still generally view the failure of the entire justice system through the lens of over-representation.

26. The CCRA , and in particular Sections 81 and 84, was a significant step by the Federal Government in enhancing Aboriginal community involvement in corrections and, over time, potentially reduce Aboriginal over-representation in federal corrections. Numerous studies have been conducted over the past decades concerning Aboriginal involvement in corrections, and all conclude that the issues bringing Aboriginal people into federal institutions go well beyond the capacity of federal corrections alone to address. The offending circumstances of Aboriginal offenders are often related to substance abuse; inter-generational abuse and trauma; residential schools; low levels of education, employment and income; and substandard housing and health care, among other factors.

27. Within corrections, Aboriginal offenders tend to be younger; to be more likely to have served previous youth and/or adult sentences; to be incarcerated more often for a violent offence; to have higher risk ratings; to have higher need ratings; to be more inclined to have gang affiliations; and to have more health problems, including Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) and mental health issues and addiction. [23]

28. While it is recognized that CSC does not have control over the number of offenders entering the federal system, it can have an impact on the number of offenders returning to a penitentiary after their release. The enhancement of Aboriginal cultural and spiritual opportunities for offenders, particularly if offered in an Aboriginal environment, is acknowledged as a positive approach to the successful reintegration of Aboriginal offenders.

USE OF SECTION 81 AGREEMENTS – ANALYSIS

29. Section 81 does not stipulate how Aboriginal communities are to manage offenders under their care and custody. Two distinct approaches have evolved over time. The first, and most common approach, is through the funding of Aboriginal Healing Lodges or Healing Centres. These facility-based centres house offenders transferred from CSC institutions and provide Aboriginal cultural, spiritual and correctional programming. The second approach is through funding agreements with Aboriginal communities that accept offenders into their community and provide custody and programs without the establishment of a formal healing centre.

30. Since the CCRA 's enactment 20 years ago, CSC has entered into four funding agreements with Aboriginal communities and organizations to support the establishment and maintenance of Healing Lodges. These facilities have a total Section 81 bed capacity of 68 spaces. (Although some CSC corporate documents refer to a total Section 81 capacity of 111 spaces, the actual figure is 68, accounting for the fact that while Stan Daniel's Healing Centre has 73 beds, only 30 are designated pursuant to a Section 81 agreement). [24]

| FACILITY | OPENING DATE | REGION | BED CAPACITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prince Albert Grand Council ( PAGC ) Spiritual Healing Lodge | 1995 | Prairie – Saskatchewan | 5 |

| Stan Daniels Healing Centre | 1999 | Prairie – Alberta | 30 |

| O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi Healing Lodge | 1999 | Prairie – Manitoba | 18 |

| Waseskun Healing Centre | 2001 | Quebec | 15 |

| TOTAL | 68 |

Source : CSC Data Warehouse

31. In September 2011, CSC increased the bed capacity of Section 81 Healing Lodges with the establishment of 16 bed spaces for Aboriginal women at the Buffalo Sage Healing Centre in Edmonton, Alberta. In addition, approval has been given to expand the O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi Healing Lodge by six spaces. The Waseskun Healing Centre is currently in discussions with CSC for the creation of a healing facility for Aboriginal women that could include six bed spaces for Section 81 transfers and two spaces for Section 84 releases. Waseskun Healing Centre is also hoping to expand its Section 81 capacity through the construction of five new bed spaces. It is important to note that these additional spaces are not the result of negotiations with new Aboriginal communities, but rather extensions of already existing agreements.

32. Not all Section 81 agreements resulted in the establishment of Healing Lodges. The Alexis First Nation in Alberta and the George Gordon First Nation in Saskatchewan signed Section 81 Community Custody Agreements to assume responsibility for the transfer of offenders. In both agreements, offenders are to be accommodated in the community and confined within the boundaries of the reserve, unless permission had been granted for an escorted temporary absence, work release or unescorted temporary absence. The offender is to be under the supervision of an individual, or individuals, approved by both CSC and the First Nation. As part of the custody plan, the offender must be given clear direction on limits on movement within the boundaries of the reserve and clear direction on times when they must be in their place of residence.

33. Further, a schedule is required that permits both the offender and affected members of the community to be aware of where the offender will be, a specific period of time where the offender is formally accounted for and a record of movement over the course of the day. Each First Nation is required to submit a budget to enable CSC to calculate a per diem rate under the agreement. The Alexis First Nation signed its Section 81 agreement in April 1999 for the transfer of up to five inmates. The George Gordon First Nation signed its agreement in June 2002. Other than one transfer to the George Gordon First Nation, no records were found to indicate that other transfers were completed. Since the George Gordon First Nation agreement was signed 10 years ago, CSC has not entered into any additional non-facility Section 81 agreements.

34. With only four Section 81 Healing Lodge agreements having been signed since the CCRA was enacted 20 years ago, the lack of movement toward enhancing Aboriginal community involvement in federal corrections, as intended by Parliament, has not been achieved.

WHY HAS PROGRESS STOPPED?

Aboriginal Community Interest Existed

35. From the time the CCRA was enacted, there has been an interest on the part of several Aboriginal communities and organizations to become involved in federal corrections through Section 81 agreements. In 2001, CSC reported that two additional Section 81 agreements were in the final drafting stage, three were in negotiation and 17 others were in preliminary discussion phase. [25] In 2002, there were two new agreements under review and an additional four under negotiation for a potential increase of 39 new bed spaces. [26]

Change in Policy Direction

36. In 2000, CSC sought additional funding to construct and operate new community Section 81 Healing Lodges and was provided with $11.9M over five years under Public Safety Canada's Effective Corrections and Citizen Engagement Initiative . [27] An essential component of Effective Corrections was to address the over-representation of Aboriginal offenders in federal prisons through enhanced participation of and collaboration with Aboriginal communities. The investigation found, however, that the Waseskun Healing Centre was the only new stand-alone Section 81 facility to be completed using Effective Corrections funds.

37. Although there was interest on the part of Aboriginal communities to enter into negotiations for Section 81 agreements, CSC 's "final" evaluation of the first installment of Effective Corrections funding, completed in June 2004, indicates that, beginning in 2001-02, CSC "re-profiled funds from Healing Lodge development to Institutional Initiatives in order to establish the Pathways Ranges." [28] According to 2002 documents reporting on how CSC planned to use Effective Corrections money, [29] funds were not to be redirected to cover other institutional costs. [30] However, this appears to be what happened, as CSC used Effective Corrections funding to pilot and subsequently expand Pathways Healing Units in medium security penitentiaries, increase the number of Aboriginal Community Development Officers, support a National Aboriginal Working Group and pilot an Aboriginal gangs initiative at Stony Mountain Institution. [31] In other words, the investigation found that Effective Corrections funding originally earmarked to enhance Aboriginal community reintegration was used largely to create new penitentiary-based interventions for Aboriginal inmates.

38. To explain the change in policy direction from community to institutional priorities, CSC 's Strategic Plan for Aboriginal Offenders 2006 to 2011 indicates that it "lacked Aboriginal-specific programs in institutions to help offenders prepare for the healing lodge environment." [32] As a result, CSC moved to "re-focus" efforts on consolidating and expanding penitentiary-based interventions for Aboriginal inmates. In effect, CSC 's experience and view during this period of "learning" and "refocus" (2000-2005) was that Aboriginal inmates were not adequately prepared to be released to alternative community arrangements and the Healing Lodges themselves lacked the management and accountability capacity and expertise to safely and appropriately support them. [33] In response to a 2002 Research Report, [34] a Healing Lodge Action Plan was adopted with specific aims to: i). strengthen internal Healing Lodge operations; ii). improve understanding of Healing Lodge programs and services by CSC ; iii) improve the transfer and selection process of candidates; and iv) improve the relationship between CSC and Healing Lodge staff. [35]

39. While some improvements were made, the documentary record indicates that CSC chose to abandon its commitment to create new Section 81 agreements and facilities at the very same time as it was receiving additional government funding to do precisely that. At the beginning of 2000, records indicate that CSC was actively negotiating with several Aboriginal communities and groups to expand section 81 agreements.

40. Effective Corrections funding was extended in 2005-2006 for another five years, to an ongoing level of $8 million per year, of which Correctional Service Canada's annual share was $4.8 million. The majority of the renewed funding ($3.7M annually) has been used to expand institutional Aboriginal Pathways "healing units" across all of CSC 's five regions. [36] No new Section 81 agreements or community reintegration facilities for Aboriginal offenders have been created since 2001. (The Buffalo Sage Healing Centre for women, which opened in September 2011, is an expansion of an existing agreement with the Native Counselling Services of Alberta .)

41. From 2001-02 to 2010-11 the Aboriginal inmate population increased by 35% for men (from 2,129 to 2,875) and 86% for women (from 98 to 182). [37] CSC 's 2012-13 Report on Plans and Priorities indicates that the Service plans to expand the number of Pathways Units to 25 operational sites across all five of its regions. [38] A similar commitment to increasing investment in Aboriginal community reintegration initiatives appears to be lacking.

BARRIERS IN DEVELOPING AND MAINTAINING SECTION 81 AGREEMENTS

Lack of Policies and Standards

42. As a previous report commissioned by the OCI pointed out, a CSC audit of Healing Lodges concluded that 16 years after the CCRA was enacted there was still no CSC policy framework in place to support the establishment of Section 81 Healing Lodges, with little direction provided in CSC policies or procedures. [39] Further, the criteria used to assess requests to enter into Section 81 agreements had not been clearly defined. There was no requirement for CSC Regions to report to National Headquarters on agreements, nor had CSC defined performance indicators for effective monitoring and reporting. [40] The 2008 audit of Section 81 management practices similarly concluded that "[W]ith the exception of monitoring Healing Lodge residents, the roles and responsibilities of CSC personnel involved with offenders prior to their placement in Section 81 Healing Lodges are not well defined, understood and followed." [41] National policy guidelines referencing the negotiation, implementation and management of Section 81 and 84 processes were finally issued in July 2010 [42] in response to the 2008 audit findings, 18 years after the enactment of the CCRA .

43. Section 81 facilities are not bound by all of CSC policies, other than those that have been developed to facilitate admissions, transfers and application processes. Even so, Section 81 facilities are expected to maintain "acceptable" programs, provide "appropriate" services and meet standards comparable to CSC . Until recently, in fact, there was little consistency in the Section 81 agreements, reflecting the relative degrees of autonomy and administrative control that were originally negotiated between CSC and Aboriginal community providers. As a consequence, each Aboriginal-operated Healing Lodge has developed its own approach to healing, rehabilitation and reintegration, consistent with its community's values, practices, traditions and beliefs. At the same time, real and perceived variations between CSC and Aboriginal-operated Healing Lodges can lead to a lack of trust and breakdown in communication. These "mixed messages" often surface in differences regarding "comparable" Section 81 funding, objectives, program content and effectiveness. The capacity of Section 81 facilities to safely and effectively manage offenders while meeting CSC service delivery standards and supervision expectations is another long-standing source of friction. [43] By far the most contentious issue is the expectation that the Section 81 facilities provide comparable services and outcomes as CSC at a considerably reduced per diem rate.

Transfer Eligibility Criteria

44. One of the factors that inhibit existing Section 81 Healing Lodges from operating at full capacity (and new Healing Lodges being developed) is the requirement that they limit their intake to offenders classified as minimum security, or, in rare cases, medium security offenders who present a low risk to public safety. [44] Allowing only minimum security inmates (or medium in exceptional cases) to be eligible for transfer to a Section 81 Healing Lodge reflects neither Parliament's intent nor CSC 's original vision. Rather, it is an internal CSC policy that has evolved to minimize its risk and exposure. This policy poses a number of problems, but is exacerbated by the fact that while 22.2% of Aboriginal offenders received a minimum-security classification under the Custody Rating Scale in 2010-2011, [45] only 11.3% were actually placed in minimum-security institutions. Compared to non-Aboriginal offenders, a lower percentage of Aboriginal male offenders are classified as minimum-security risk. [46] That percentage has decreased over time: [47]

| Region | 2006-2007 | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incarcerated | Minimum | % | Incarcerated | Minimum | % | Incarcerated | Minimum | % | |

| Atlantic | 133 | 30 | 22.5% | 114 | 14 | 12.3% | 116 | 16 | 13.8% |

| Quebec | 300 | 71 | 23.6% | 285 | 25 | 8.8% | 331 | 21 | 6.3% |

| Ontario | 438 | 68 | 15.5% | 418 | 22 | 5.3% | 438 | 27 | 6.2% |

| Prairies | 1,908 | 520 | 27.2% | 1,453 | 154 | 10.6% | 1,606 | 205 | 12.8% |

| Pacific | 616 | 150 | 24.3% | 466 | 63 | 13.5% | 485 | 68 | 14.0% |

| Total | 3,395 | 839 | 24.7% | 2,736 | 278 | 10.2% | 2,976 | 337 | 11.3% |

Source : CSC Data Warehouse.

Note: Data reflects male inmates with valid security classification.

45. The data indicates that CSC 's policy criteria effectively exclude about 90% of Aboriginal federal offenders from being considered for transfer to a Healing Lodge. In 2010-11, there were a total of 337 Aboriginal men accommodated in minimum security facilities, or about 11% of all Aboriginal men in federal institutions.

46. It is significant to note that Section 81 Healing Lodges could operate at full capacity even if they only accommodated minimum security inmates. In 2009-2010 and 2010-2011, Section 81 Healing Lodges accommodated less than 25% of Aboriginal male minimum-security inmates: [48]

| Region | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum Security Inmates | Section 81 Healing Lodge Beds | % | Minimum Security Inmates | Section 81 Healing Lodge Beds | % | |

| Atlantic | 14 | 0 | 0% | 16 | 0 | 0% |

| Quebec | 25 | 15 | 60% | 21 | 15 | 71% |

| Ontario | 22 | 0 | 0% | 27 | 0 | 0% |

| Prairies | 154 | 53 | 34% | 205 | 53 | 26% |

| Pacific | 63 | 0 | 0% | 68 | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 278 | 68 | 24% | 337 | 68 | 20% |

Source : CSC Data Warehouse. Year End Snapshot of the average "physically-in" count for March 31, 2010 and March 31, 2011.

47. Section 81 Healing Lodges do not exist outside the Prairie and Quebec Regions, although there is a clear indication that there is a need for, and capacity to fill, Healing Lodges in the Pacific, Ontario and Atlantic Regions, as well as in the North. Without a Healing Lodge in these regions, either Aboriginal offenders are denied the opportunity to avail themselves of a community healing environment or they are transferred to a facility where they face the prospect of losing contact with their families and home communities. (A similar comparison for Aboriginal female offenders cannot be made, as there were no Section 81 bed spaces for Aboriginal women until 2012.)

48. In 2011, 1,009 offenders were informed about Section 81 opportunities and 593 expressed an interest in a transfer. [49] Based on these numbers, it is unclear why the Healing Lodges were not filled to capacity. For Section 81 Healing Lodges, the average "physically-in" count for fiscal years 2009-2010 and 2010-2011 is shown below: [50]

| Healing Lodge | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | Count | % | Count | % | |

| PAGC Spiritual Healing Lodge | 5 | 4 | 80% | 4 | 80% |

| O-Chi-Chak-Ko-Sipi Healing Lodge | 18 | 13 | 72% | 13 | 72% |

| Stan Daniels Healing Centre | 30 | 13 | 43% | 22 | 73% |

| Waseskun Healing Centre | 15 | 13 | 86% | 10 | 66% |

| Total/Average Percentage | 68 | 43 | 63% | 49 | 72% |

Source : CSC Data Warehouse. Year End Snapshot of the average "physically-in" count for March 31, 2010 and March 31, 2011.

Funding and Permanency of Section 81 Healing Lodges

49. Without a doubt the two greatest inhibiting factors to the establishment of new Section 81 Healing Lodges, which are in fact intertwined, are funding and permanency. While federal penitentiaries and CSC -operated Healing Lodges are permanent institutions and treated as such, Section 81 Healing Lodges are on five-year contribution agreement cycles and enjoy no sense of permanency. Nor does entering into a Section 81 agreement necessarily create an economic benefit to Aboriginal communities and organizations. On the contrary, those agreements can create a serious disadvantage, particularly if the bed occupancy rate is lower than forecasted. There are no guarantees that the agreements will be renewed, and they are subject to potential changes in CSC policy priorities and funding pressures. In at least one case, a Section 81 Healing Lodge has had its agreement subject to six-month extensions while negotiations proceed towards a new five-year agreement. [51]

50. The discrepancy in funding between Section 81 Healing Lodges and those operated by CSC is substantial. In 2009-2010, the allocation of funding to the four CSC -controlled healing lodges totalled $21,555,037. For the same period, the amount associated with Aboriginal-controlled Section 81 Healing Lodges totalled $4,819,479. [52] It should be noted that the funding to Section 81 Healing Lodges included funds for expenditures relating to the operation of CSC Regional Headquarters and Section 81 Healing Lodges receive funds for residents under conditional release. The cost per offender at CSC -controlled Healing Lodges is approximately $113,450 whereas it is $70,845 at Aboriginal-controlled facilities, or about 62% of the CSC rate.

51. The under-funding of Healing Lodges means that they are unable to provide wages comparable to that earned by CSC employees. For example, at Stan Daniels Healing Centre, as recently as 2011 a lack of funding resulted in some staff being let go while remaining staff were given a 1% cost of living increase. Funding inequity and instability leads to frequent staff turnover and cycles of layoffs, resignations, new hires, etc. A 2005 Evaluation Report of Stan Daniels indicated that while the facility is cost-effective in providing similar correctional results at a lower cost, changes in the funding formula were nevertheless required to take into account the higher supervision costs in meeting the needs of an increasing proportion of statutory release residents. [53]

52. Aboriginal offenders tend to be assessed in higher need and/or higher risk categories on account of previous criminal history, including more extensive involvement in the criminal justice system, as well as employment, family, substance abuse, mental health and community reintegration factors. Costs to house and supervise special needs groups and individuals in the community are increasing. Section 81 funding formulas should reflect the operating realities associated with an increasingly complex needs profile and caseload.

53. Section 81 Healing Lodge agreements require their staff to have a wide range of competencies – from offender supervision, awareness of CSC procedures and protocols to financial reporting. These present a burden for most Aboriginal communities and organizations that have not had a previous relationship with CSC or exposure to CSC procedures. Preparing detailed financial reports that are required for all contribution agreements with the Federal Government is also time-consuming and technical. Further, existing Section 81 Healing Lodges have reported that the burden placed on them by CSC for reporting, while at the same time limiting funding for staff positions has been a cause of high staff turnover and burnout. Healing Lodge staff have complained about the lack of training opportunities available to them from CSC , which, because of high staff turnover, needs to be ongoing. In some cases, the Section 81 Healing Lodges have become training grounds for Aboriginal people who then leave those facilities to work for CSC .

54. The movement of employees to CSC is not unexpected. CSC can offer many advantages that Section 81 Healing Lodges cannot. Staff salaries can be upwards of $25,000 to $30,000 more in CSC facilities. Those moving to CSC enjoy working in a stable unionized workplace. The Native Counselling Services of Alberta estimates that it costs Section 81 Healing Lodges approximately $34,000 to fully train an employee to CSC standards, but they receive no direct compensation for that training.

55. Because Section 81 agreements are five years in duration, little or no flexibility exists for Healing Lodges to meet unexpected demands on their budgets. Improvements to their infrastructure, due to either emergencies or CSC security-related requirements, cannot take place on a timely basis without either seeking additional funding from CSC or re-profiling their budget by reducing staff and/or services. One of the most significant pressures on healing lodge operations is changes to insurance coverage. Insurance companies, which are hesitant to take any undue risk, pressure Healing Lodges to abide by the full range of federal corrections standards and procedures or face a significant increase in the cost of liability coverage. For example, at one Centre, its costs to maintain insurance increased by $28,000 this past year alone with no increase in funding provided by CSC . Not only did it have to absorb the increased cost of insurance, but it was also pressured by its insurance company to follow CSC security-related procedures, which it felt were inconsistent with an Aboriginal approach to healing.

56. The findings of this section point to weaknesses, discrepancies and barriers in CSC 's approach to Section 81 Healing Lodges. Lack of equitable salaries, chronic under-funding and lack of permanency for Section 81 facilities raise questions of fairness and equity and further contributes to conditions of systemic disadvantage for Aboriginal offenders.

BARRIERS IN THE ABORIGINAL COMMUNITY

57. Another factor that has been recognized as inhibiting the growth of Section 81 Healing Lodges has been community acceptance. Just as with many non-Aboriginal communities, many Aboriginal communities are not prepared to have offenders released to their community or to take on the responsibility of managing offenders. This reaction may be due to the lack of personnel, programs and services available in the community to meet the offender's needs, or a fear of potential victimization by the offender. Band elections in First Nations are other variables that cannot be ignored, as a change in leadership can often result in changing priorities and the cessation of negotiations with CSC .

58. With the exception of Stan Daniels Healing Centre, the other Section 81 Lodges are in rural or remote communities. Their relative isolation makes it harder to accept offenders with medical or mental health issues who require transportation or specialized staff to meet their medical needs. A significant percentage of Aboriginal offenders are excluded from being transferred to a Healing Lodge by virtue of being active gang members or, in some cases, sex offenders.

CSC -OPERATED HEALING LODGES

59. In addition to the four Section 81 Healing Lodges, CSC has established four Healing Lodges that are operated as CSC minimum security institutions (with the exception of the healing lodge for women that accepts both minimum and medium security inmates).

| FACILITY | OPENING DATE | REGION | CAPACITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge | 1995 | Prairie – Saskatchewan | 44 |

| Pe Sakastew Centre | 1997 | Prairie – Alberta | 60 |

| Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village | 2001 | Pacific – British Columbia | 50 |

| Willow Cree Healing Lodge | 2003 | Prairie – Saskatchewan | 40 |

| Total | 194 |

60. CSC -operated Healing Lodges can provide accommodation for up to 194 federal incarcerated offenders, which includes 44 beds for Aboriginal women. Approval has recently been given for the Willow Cree Healing Lodge to expand by an additional 40 bed spaces for male offenders, bringing the overall capacity for CSC - operated Lodges to 230.

61. Although CSC -operated Healing Lodges fall outside the scope of this investigation, they are relevant for two reasons. Primarily, there is the perception among some Section 81 Healing Lodge staff and CSC officials that CSC -operated Healing Lodges are in competition with Section 81 Healing Lodges for minimum security inmates. Both

Pe Sakastew Centre and Willow Cree Healing Lodge are in close proximity to the Stan Daniels Healing Centre and the PAGC Spiritual Healing Lodge, respectively. The CSC -operated Healing Lodges have an average bed count that is between 13% and 17% higher than for Section 81 Healing Lodges. [54]

| CSC Healing Lodge | 2009-2010 | 2010-2011 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacity | Count | % | Count | Percentage | |

| Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge | 44 | 36 | 82% | 40 | 91% |

| Willow Cree Healing Lodge | 40 | 38 | 95% | 39 | 97% |

| Pe Sakastew Centre | 60 | 46 | 77% | 52 | 87% |

| Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village | 50 | 32 | 64% | 31 | 62% |

| Total/Average Percentage | 194 | 152 | 80% | 162 | 85% |

Source : CSC Data Warehouse.

62. Second, CSC did not intend to operate its Healing Lodges in competition with Section 81 facilities, but rather saw itself as providing an intermediate step that would ultimately result in the transfer of those facilities to community control under Section 81 agreements. Accordingly, negotiations were initiated with the Nekaneet First Nation for the transfer of the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge to First Nation control and with the Samson First Nation for the transfer of the Pe Sakastew Centre. However, these negotiations never proceeded past the preliminary stages for three reasons:

- First Nations communities with CSC -operated Healing Lodges enjoy the benefits of having a facility in their community without assuming full responsibility;

- CSC Healing Lodges provide stable employment for band members that could not be enjoyed if they were under Section 81; and

- The funding provided to Section 81 Healing Lodges is substantially lower than that of CSC facilities.

63. As some key informants noted, another reason for ceasing negotiations was that CSC did not engage the Chief and Council in a meaningful way, and this lack of partnership created a long-standing sense of acrimony and mistrust between the two parties. This lack of community engagement with CSC -operated Healing Lodges has been raised in the Service's evaluation of Healing Lodges [55] and during the course of this investigation. For example, leadership of the Nekaneet First Nation feel that the original vision for the Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge has been lost, and the community has taken a "hands off" position until it is revisited and acknowledged by CSC . Similarly, the Samson Cree First Nation has begun to question the value of the Pe Sakastew Centre, given that it has also moved away from the community's vision of a healing lodge and has not provided the level of employment to community that members originally expected. Moreover, when community members are hired, they occupy low level positions with few opportunities for advancement. As a result, there has been some discussion in the community about changing the Pe Sakastew Centre into a substance abuse treatment centre.

64. A notable exception to the lack of community engagement is found at the Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village. This facility is given strategic direction by a community Senate that provides advice to a co-operative board made up of representatives from both the community and the Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village. Further, the Chief and one other member of the Chehalis First Nation sit on the facility's Citizens' Advisory Committee. There is also a strong relationship with the Chehalis Cultural Centre and Elders from the community play a key role in ensuring that the proper protocols are acknowledged and used at the Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village. As a result, staff and inmates are invited to almost every ceremony in Chehalis and community members are invited to participate in ceremonies at the facility. The First Nation has hired a community engagement officer to work with the Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village.

USE OF SECTION 84 RELEASES – ANALYSIS

65. Section 84 speaks to Parliament's intent to transfer some responsibility for federal corrections to Aboriginal people. Section 84 differs substantially from Section 81 in that it is directive and not permissive. To that end, Commissioner's Directive 702 was rewritten in 2008 to state that the Regional Deputy Commissioner will ensure Aboriginal communities are engaged in the reintegration process for consenting Aboriginal offenders returning to those communities pursuant to section 84 of the CCRA . [56]

66. Determining the number of successful Section 84 release planning processes is problematic. It was only in 2008 that CSC 's Offender Management System developed a screen for tracking Section 84 and there is inconsistency in its use across the country. This impacts upon CSC 's ability to extract accurate information about the use and effectiveness of Section 84 release processes. [57]

67. The numbers for successfully completed release plans developed and presented to the Parole Board utilizing Section 84 fluctuates dramatically, from a recorded high of 226 in 2005-06 to 51 in 2006-07, 60 in 2009-10 and 99 in 2010-11. These relatively low numbers cannot be explained solely by a lack of interest on the part of Aboriginal inmates, especially given that 593 offenders expressed an interest in Section 84 releases in 2010-2011. [58] A few reasons can be offered to explain the discrepancy between interest and take-up. For example, the investigation found that there are only 12 Aboriginal Community Development Officers ( ACDO s) across Canada whose role is to bridge the interests of the inmate and the community prior to release. ACDO caseloads are often large and focus on an individual case can easily be distracted. The Safe Streets and Communities Act (2012) now includes statutory release within the scope of Section 84. This may increase the number of interested offenders wishing to explore this option.

68. A section 84 Conditional Release Planning Kit has been produced and widely distributed throughout CSC and to communities to provide a comprehensive guide on this release option. [59] The kit outlines 25 tasks that are necessary to complete a Section 84 release plan. These tasks are shared by inmates, Primary Institution Workers, Institutional Parole Officers, ACDO s, Parole Officers and Aboriginal communities or organizations. The process is complex and requires a number of time-sensitive and co-ordinated actions.

69. Several individuals interviewed were of the view that Section 84 is not well-understood by correctional authorities and that the process to complete a Section 84 release is too lengthy, cumbersome and frustrating. Problems can arise at the very beginning of the process when an inmate is required to write a letter of interest to the community he or she wishes to be released to. This raises issues of disclosure of personal information on the part of the inmate, which he or she may not want shared with the community in which the victim, or family, may reside. Release plans can be stopped by a change in the community's leadership following elections, or in some cases, by not knowing the appropriate person in the community who can be responsible for making a decision.

70. Another problem is resources. Communities are not compensated for monitoring an offender's compliance with Section 84 conditions. CSC , however, does make provision for the payment of services where it is required in a release plan. Program and transportation costs are supposed to be reflected in the plan, although there are no guarantees that those costs will be covered by CSC . The decision to cover those costs is made on the basis of how the course or program addresses the offender's needs and the availability of funds. [60] The fact that CSC can determine the validity of programs to support a released offender's healing and reintegration, and not the Aboriginal community itself, is viewed as patronizing by many Aboriginal people and communities.

71. Some of those interviewed felt that the intent of Section 84 is misunderstood by some officials who wrongly believe that offenders were only to be returned to a First Nation community if they agreed to follow a traditional healing path. (This is not the case in the Prairie Region, where ACDO s will work with all faith communities to ensure that Aboriginal offenders have the support from their religious denomination to continue their spiritual journey.) The perception that Section 84 releases should focus on First Nation communities is not in accord with the reality that the majority of Aboriginal offenders will be released to urban centres. More attention needs to be paid to developing relationships with urban Aboriginal organizations – such as has been done with the Circle of Eagles Lodge in Vancouver and Friendship Centres in Saskatchewan – to develop the understanding and capacity to accept Section 84 released offenders.

72. A common concern raised was that there were too few ACDO s to develop the necessary relationships with First Nation and urban Aboriginal communities in addition to keeping a caseload that can exceed 100 clients. One option to reduce the amount of work required to facilitate Section 84 releases is to involve Aboriginal collective organizations in acting as an "agent" on CSC 's and the offender's behalf.

73. Some work has been done in that regard. The Mi'kmaq Legal Support Network ( MLSN ) in Nova Scotia has worked with CSC , Parole Board of Canada and Aboriginal Affairs Canada to develop a template/protocol to facilitate the release and healing of offenders from provincial and federal correctional institutions. The protocol is designed to enhance the capacity of Mi'kmaq communities to safely reintegrate offenders into their communities in a cohesive manner by developing relationships between and among the offender, the community, MLSN and governments, thereby allowing communities to provide effective healing processes through the implementation of new programs and approaches. The protocol has the capacity to accelerate community capacity to determine the nature of their involvement with offenders and victims to implement strategies designed to support the successful release of offenders. [61]

74. Under this protocol agreement, the MLSN will take an active role in Section 84 releases. In partnership with CSC , the MLSN will arrange for the offender to receive a temporary absence that will enable him or her to sit in a circle with the community to discuss accountability and issues of concern to all parties. As much as possible, these circles are in the community. Following the circle, a release plan is prepared for inclusion in the offender's parole application. Section 84 Committees are also established to consult with community members and leadership on those activities and responsibilities that the community is prepared to assume in support of a released offender. These appear to be an emerging set of best practices.

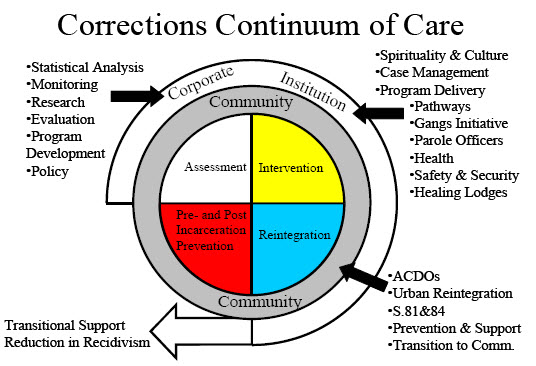

CSC 'S CONTINUUM OF CARE MODEL FOR ABORIGINAL CORRECTIONS

75. A review of CSC 's Continuum of Care Model for Aboriginal Offenders and the Circle of Care for Aboriginal Women is outside the scope of this investigation. However, this Continuum impacts on both Section 81 and 84 initiatives. Developed and implemented in 2003 in consultation with Aboriginal stakeholders, the Continuum and Circle of Care integrates culturally appropriate and spiritually significant interventions throughout an offender's sentence. The Continuum begins at intake, followed by paths of healing throughout institutional placement, and ends with the successful reintegration of Aboriginal offenders into their community. [62] This model, and the approach taken by CSC to improve corrections for Aboriginal offenders, should be seen as a major step forward compared to only three decades ago when Sweetgrass was routinely banned in federal institutions and Elders were not given the respect they deserved.

76. Both Sections 81 and 84 are integral pieces of the reintegration phase of the model. As a result, all of the preceding elements of the model, from assessment through the Pathways initiatives to all aspects of programming, need to work toward producing the maximum benefits for inmates as they proceed through their healing journey. Should any element of the Continuum not function as intended, the offender's healing journey will not be as effective as expected, may result in longer portions of their sentence being served in an institution and delay opportunities for offenders to take advantage of Sections 81 and 84.

77. Pathways units in medium security institutions [63] are evolutionary in that they were originally established to provide a greater number of Aboriginal offenders with more culturally appropriate environments at a time when Section 81 facilities were not being utilized at full capacity. Pathways provide an alternative environment that supports offenders who have made a demonstrated commitment to traditional activities, ceremonies and healing. In 2010-2011, 18.2% of the total Aboriginal inmate population spent time in a Pathways unit with some promising results. Pathways offenders received transfers to lower security institutions at a higher rate than most of the Aboriginal population, positive urinalysis results were lower and they were more likely to obtain a discretionary release. [64]

78. It is not an understatement to say that Elders play a pivotal role in healing by providing ceremony, guidance and support to Aboriginal offenders. At a meeting with Elders and Aboriginal program staff at Saskatchewan Penitentiary a number of concerns and issues were raised that result in inhibiting the healing of Aboriginal inmates in institutions and impact their ability to be transferred to a lower security institution and eventually to a Healing Lodge. Elders at Section 81 and CSC -operated Healing Lodges are integral to the healing environment but are faced with many of the same problems faced by CSC institutional Elders. Due to budgetary constraints, Elders are not able to provide the time and level of care they feel are essential to meet the needs of their clients and promote the healing environment of those lodges. A more thorough investigation of Elders and their role within CSC 's Continuum of Care approach appears warranted.

IMPLEMENTATION OF GLADUE PRINCIPLES IN FEDERAL CORRECTIONS

79. The Gladue Supreme Court decision arises from Section 718(e) of the Criminal Code that states a court shall impose a sentence that takes into consideration that "all available sanctions or options other than imprisonment that are reasonable in the circumstances should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of Aboriginal offenders." [65] This section of the Criminal Code was introduced in 1995 to deal with concerns about the overuse of incarceration as a means of addressing crime, particularly as it applied to Aboriginal peoples. Parliament recognized that the over-representation of Aboriginal offenders in prisons was systemic and race-related, and that the mainstream justice system was contributing to the problem. Since the enactment of this section of the Code in 1996, courts across Canada have been mandated to exercise restraint in imprisonment for all offenders, but particularly for Aboriginal people. [66]

80. Citing Gladue in R. v. Ipeelee ( SCC , March 2012), [67] the Supreme Court again called upon judges to use a different method of analysis in determining a fit sentence for Aboriginal offenders by paying particular attention to the unique circumstances of Aboriginal offenders. In so doing, Canada's highest court called for culturally appropriate sanctions to be handed down for Aboriginal offenders. A reasonable interpretation of these decisions is that Gladue principles should be applied to all areas of the criminal justice system in which an Aboriginal offender's liberty is at stake.

81. CSC has committed to incorporating Gladue considerations into Aboriginal corrections at the policy and operational level. Aboriginal social history considerations can include, but are not limited to: effects of the residential school system, family or community history of suicide, experience in the child welfare or adoption system, experiences with poverty, level or lack of formal education, and family or community history of substance abuse. Training on Gladue principles has recently been provided to some staff on a pilot basis. Commissioner's Directive (CD) 702 (Aboriginal Offenders) provides that all CSC staff will consider an Aboriginal offender's social history when making decisions concerning security classification, reclassification to security levels, segregation placements and conditional release, among other factors. [68] Several other CDs integrate Gladue principles, including 705-6 (Correctional Planning and Criminal Profile), 705-7 (Security Classification and Penitentiary Placement), 710-6 (Review of Offender Security Classification) and 712 (Case Preparation and Release Framework). [69]

82. Gladue principles, and the Commissi oner's Directives that support them, should have a significant impact on an Aboriginal inmate's access to Section 81 Healing Lodge space and programs. Application of Gladue principles should help to ensure Aboriginal inmates are placed at an appropriate security level, have access to cultural and correctional programs to begin their healing journey and opportunities to cascade down to minimum security institutions. Placement in a Section 81 Healing Lodge is a natural progression in an Aboriginal offender's healing and eventual reintegration and may be seen as responsive to the Supreme Court's view that culturally appropriate measures should be available for Aboriginal offenders.

83. However, it is far from clear as to how Gladue principles are being applied in federal corrections. Consultations with CSC and Healing Lodge staff revealed a common theme that the principles set out in Gladue, and the intent of CD 702 was not well understood, nor did those consulted present concrete ideas about how they could be implemented. CSC has developed and piloted a staff training module on Gladue principles, but the impact of that training on the day-to-day treatment of Aboriginal offenders will not be known for some time.

84. The pilot training revealed that institutional staff held a common, but mistaken, belief that Gladue social histories should only be written for Aboriginal offenders who are following a traditional path and working with an Elder, when in fact CSC policy directs that Gladue applies to every Aboriginal offender upon admission to a federal institution. [70] This and other misconceptions point to a need for adequate Gladue training for all CSC staff involved in making decisions that affect the liberty of Aboriginal offenders. Concern was also raised during interviews that the inappropriate use of Gladue principles, particularly during the assessment period, could result in offenders being placed in a higher level of security classification, thereby limiting access to programming. CSC 's Strategy for Aboriginal Corrections Accountability Framework provides that it will comply with the Gladue decision. The Aboriginal Corrections Accountability Framework Year End Report 2010-2011 , however, makes no mention of Gladue or achievements in implementing the direction set out in CD 702, four years after the policy was originally promulgated.

CONCLUSION

85. This investigation concludes that CSC has not met Parliament's intent for section 81 and 84 of the CCRA . CSC has not given Section 81 agreements priority, nor have they become a viable alternative to CSC -controlled institutions.

86. Section 81 of the CCRA , particularly when sub-sections (a) and (c) are read together, clearly directs CSC to take a new and different approach to address the chronic over-representation of Aboriginal people in federal corrections. Parliament intended that CSC share control and responsibility, though not jurisdiction, with Aboriginal communities and organizations for the care and custody of Aboriginal offenders.

87. CSC has had two decades to address issues of relationship, trust and risk management in the implementation of Section 81. However, by 2011 there were only four Section 81 Healing Lodges, with a total bed capacity of 68, and no Section 81 Healing Lodges in British Columbia, Ontario, the Atlantic Provinces or the Territories. The bed capacity of Section 81 Healing Lodges, if operated at full capacity, can only accommodate 2% of Aboriginal inmates in federal corrections, or 20% of those inmates classified as minimum security. Until very recently, in fact, there has been neither a policy framework in place to support the establishment of Section 81 Healing Lodges nor criteria to assess proposals from Aboriginal communities to develop a Section 81 Healing Lodge or a non-facility-based approach to offender custody. No new stand-alone Section 81 facilities have been added since 2001, despite a near 40% increase in the Aboriginal incarcerated population between 2001-02 and 2010-11. [71]

88. The result is that the four existing Section 81 Healing Lodges are in a precarious position. They face insecurity due to the lack of permanent and adequate financial resources to meet ongoing operational and infrastructure costs. These are major factors inhibiting the success of existing facilities and expansion of new Section 81 Healing Lodges. Staff are underpaid and have little capacity to improve their salaries, which can result in either worker burnout or seeking employment in CSC , where there are better wages and job security. Section 81 Healing Lodges receive no compensation or recognition for the value-added they provide to corrections by virtue of volunteer support and staff training and upgrading. These are significant barriers to transferring existing CSC -operated Healing Lodges to community control under Section 81 and to communities being willing to negotiate agreements under Section 81.

89. While the policy of transferring only minimum security offenders gives a degree of comfort to both Section 81 and CSC -controlled Healing Lodges, its benefits do not outweigh the problems it creates. CSC should work with Section 81 Healing Lodges to seek ways of allowing those Healing Lodges to determine which offenders would benefit from the lodge's healing approach, regardless of their security classification, without jeopardizing the facility's physical and healing environment.