June 30, 2021

The Honourable Bill Blair

Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 48th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigators Message

National Updates and Significant Cases

National Level Investigations

2. A Review of Women’s Corrections 30-Years since Creating Choices

3. Preliminary Observations on Structured Intervention Units

4. An Investigation of the Use of Medical Isolation in Federal Corrections

5. An Investigation into a Suicide in a Maximum Security Facility

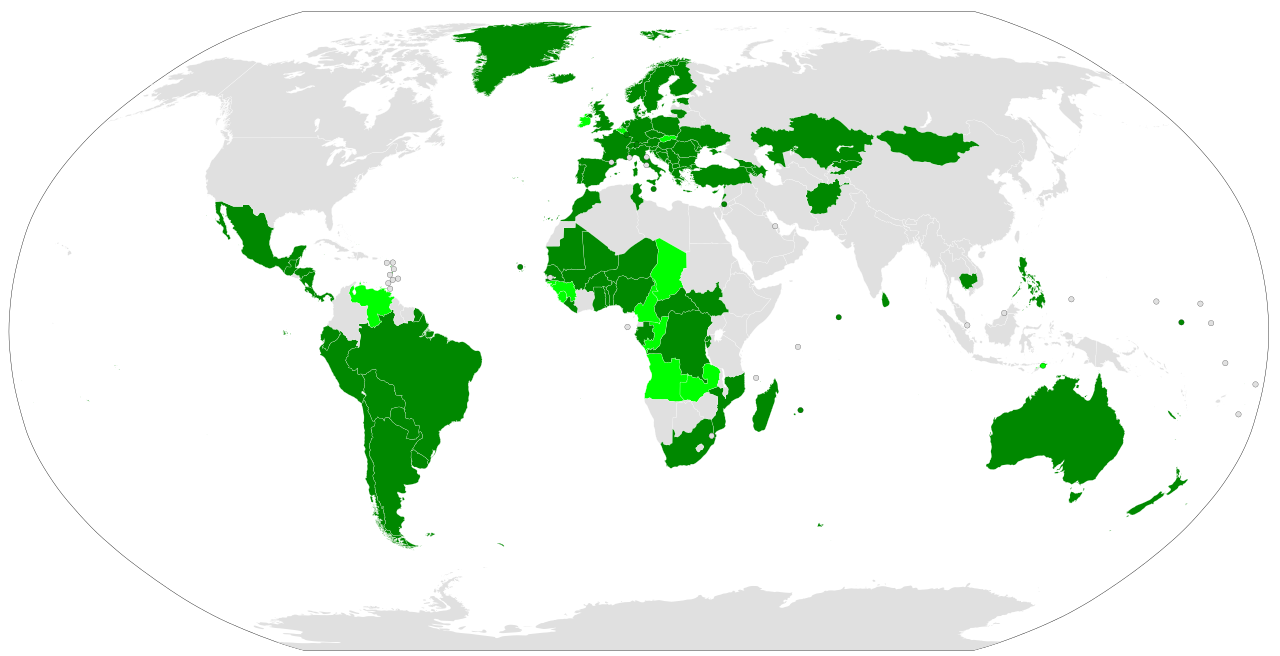

6. Canada’s Ratification of the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture (OPCAT)

Correctional Investigator’s Outlook for 2021-2022

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Correctional Investigator's Message

Dr. Ivan Zinger,

Correctional Investigator of Canada

I write the opening message to my 2020-21 Annual Report in the midst of the third wave of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Months from now, when my report has been tabled in Parliament and publicly released, I hope that the worst of these very difficult times will be behind us. It has been extremely challenging to fulfill particular aspects of my mandate when regular visits to federal prisons by my staff members continue to be suspended. Though my Office moved to a virtual visits model in early 2021, an approach that allows my investigators to confidentially interview prisoners by remote video link-up, nothing replaces in-person visits. The added value of my Office’s work rests in the ability of investigative staff to develop a personal rapport and dialogue with incarcerated individuals and prison staff, conduct in-person interviews, experience and inspect first-hand the lived realities of incarceration, and seek to resolve issues informally on site. I look forward to the day when my staff and I have returned to the office and in-person visits to prisons have resumed.

In the meantime, at the risk of being overly optimistic, I want to take this opportunity to share some thoughts and findings, based on the work of my Office, on how the pandemic has affected federal corrections. My intent is to reflect on this experience in a way that could help guide or shape the way forward for corrections in a post-pandemic world. I will conclude with some reflections on how my Office conducted business in these times of COVID-19 and will introduce some of the (non-COVID) investigations completed during this reporting period.

I think that it is fair to say that the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), like the rest of the country, was not adequately prepared to meet the scourge of a rapidly evolving global pandemic. Understandably, there was considerable concern, confusion and even panic as the first wave of COVID-19 (end of March to end of May 2020) led to outbreaks at six penitentiaries in British Columbia, Quebec and Ontario. In the initial wave, 361 prisoners contracted the virus. A second, more-virulent wave of prison outbreaks took hold in early November with new positive case counts peaking in mid-December. By the end of the reporting period (March 31, 2021), during COVID’s third wave, CSC had reported 1,450 infections among prisoners, with 21 institutions out of 43 experiencing an outbreak. Approximately ten percent of all prisoners have had a positive COVID-19 diagnosis, which is a significantly higher rate of infection than in the Canadian population. Footnote 1

COVID-19 infected units at Port Cartier Institution

Of course, statistics do not tell the whole story. Behind the aggregate numbers lie some sobering realities. Quite simply, some individuals and some institutions fared better than others. For example, proportionally more institutions in the Prairie region experienced outbreaks (7 of 12) compared to the other regions. In my second COVID-19 status update report (February 2021), I reported, with concern, that Indigenous individuals accounted for close to 60% of all positive COVID-19 cases in federal prisons since November. Demographically, Indigenous peoples behind bars are relatively younger than other racial groups. Accordingly, the higher infection rates among Indigenous peoples considerably lowered the overall age of those infected.

I also noted at that time that there appeared to be a connection between transmission rates and the infrastructure, age and design of prisons. For example, Saskatchewan Penitentiary and Stony Mountain Institution, two of the oldest and largest prisons in Canada, experienced the highest number of COVID-19 infections, including multiple outbreaks. Both institutions house a large number of Indigenous individuals, who have suffered a higher infection rate than other groups. Also, the oldest parts of these institutions have poor ventilation, large and open congregate spaces, and cells with open bars.

At the same time, despite their substantially smaller numbers, female prisoners experienced virtually the same percentage of infections (11.8%) as their male counterparts (11.7%). Footnote 2 This was likely a consequence of the congregate housing and living arrangements at the regional women’s sites.

While the COVID-19 spread among the prison population often mirrored what was happening in the community, the differential rates of infection and the uneven spread of COVID-19 between and among the prison population would benefit from further examination. Transmission vectors (from outside to inside), community and prison rates of spread, containment and isolation measures, cleaning and hygiene protocols, and infection prevention and control measures should all be carefully scrutinized and examined for both vulnerability and resiliency. This work would help inform future prevention, surveillance and response efforts, and ideally should be conducted independent of the prison service.

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety engage the Public Health Agency of Canada to conduct an independent epidemiological study of the differential rates of COVID-19 infection and spread in Canadian federal prisons and report results and recommendations publicly.

The measures adopted to contain, control and prevent active outbreaks in prison—the indefinite suspension of in-person visits, extended periods of lockdown and cellular confinement, interruption of programs and services, restrictions on yard and out-of-cell time, and the imposition of 14-day medical-isolation periods—have been exceptionally difficult and depriving for people living behind bars. At the time of writing this report, most prisons remain closed to visits and some individuals have not had a contact visit in more than a year. Other extreme measures—near-total cellular isolation (22 hours or more per day), fresh-air exercise once every two or three days, 20 minutes out-of-cell time every other day to shower or use the telephone—violate domestic law and international human rights standards. Perhaps not surprisingly, a number of prison health indicators—use-of-force incidents, number of natural deaths in custody, prisoners engaging in self-injurious behaviours—ticked upward this year, suggestive of a possible pandemic “bump” and perhaps indicative of how some prisoners cope in times of extreme stress, uncertainty and anxiety.

In my initial update, I reminded correctional and public health authorities that even in the midst of a public health emergency, fundamental human rights and dignity must still be respected. Moreover, the same measures and protections recommended by national public health authorities must be provided to correctional populations. Equivalence-of-care principles and duty-of-care obligations apply regardless of one’s status or emergency. The unusual hardships and extraordinary conditions imposed by COVID-19 on correctional populations and the issue of remedies may have to be resolved through the courts. The point, however, that prisoners’ rights required curtailment or suspension in the interest of public health and safety is one worth recognizing, as we consider the lessons learned from the pandemic.

Pandemic measures and restrictions widened gaps in the system. They exposed the lack of a medical parole framework that would have allowed some medically compromised or elderly individuals who met legislated criteria a mechanism to seek early release from prison on health grounds. In my investigation of aging and dying behind bars, I called for such a mechanism, only to be met by silence. While there is a framework by which individuals can be granted parole by exception, only a handful are approved each year, a number which remained relatively unchanged over the course of the pandemic. The continued absence of action to find a practical and cost-effective reform caused unnecessary pain and suffering throughout the COVID-19 health crisis. It could have been avoided.

In the same vein, the realities of the pandemic highlighted the widely known and well-documented inadequacies in program access and capacity behind bars, and further exposed barriers to reintegration in a system that has unfortunately refused to update its technological and service-delivery platforms for prisoners. When the pandemic struck, there was simply no capacity to support on-line or virtual learning or correctional programming of any kind in a federal penitentiary. When program interventions—educational, vocational and correctional—were suspended or curtailed by pandemic measures and staff reductions, there wasn’t enough bandwidth or infrastructure to pivot to remote, digital or e-learning platforms, beyond video visits. Our investigation into correctional interventions conducted during the second wave of the pandemic found that reductions or interruptions in programs delayed parole hearings and community release. As a result, through no fault of their own, incarcerated individuals who were eligible for community supervision spent more time behind bars than they would have in normal times.

The pandemic also laid bare a model of program service delivery that is obsolete and inexplicably information-depriving. Stuck somewhere in the early 1990s, it is a system that has failed to provide people behind bars with access to computers that do not rely on CD-ROMs or floppy disks to operate or update. In our prisons, supervised access to email or the Internet is non-existent, yet these are widely available in prisons throughout the industrialized world. In my investigation last year of learning behind bars, I noted that our federal prisons are falling further behind the rest of the industrialized world. They are not providing those who are incarcerated with the vocational skills, education and learning opportunities they need to return safely to the community and live productive, law-abiding lives. The sole recommendation from that report, like so many before it, was met by bureaucratic resistance and government inertia. Had the Service adopted or advanced recommendations from my last annual report, many of the problems that were amplified by pandemic conditions could have been reduced or avoided altogether.

It is important to acknowledge that, as bad as things were, they could have been a whole lot worse. In my last COVID-19 update, I cited a number of initiatives that have helped CSC to limit infection rates. Countless staff made exemplary efforts and personal sacrifices to continue working through the pandemic. I witnessed this dedication first-hand in visits to institutions in Quebec and Ontario during the first and second waves of the pandemic. Extraordinary commitment, selfless service and duty to others by CSC staff should be acknowledged and commended. Other bright spots in CSC’s pandemic response include:

- Access to rapid COVID-19 testing;

- Universal campaign to vaccinate correctional populations and staff;

- Early vaccination of medically compromised and elderly individuals in custody;

- Expansion of video visitation capacity;

- Collaboration with external disease infection, prevention, control and response agencies and experts; and,

- Deliberate, focused and enhanced communication with external stakeholders and families about the latest developments in CSC’s pandemic response.

These measures have undoubtedly made a positive difference and saved lives.

I would be remiss if I did not mention the commitment and courage of the not-for-profit community corrections sector and the hundreds of staff, volunteers and facilities that kept their services running and doors open to individuals returning to the community during this crisis. The community corrections sector is truly one of the unheralded and unsung heroes of these times, especially considering that prison release rates throughout the pandemic have remained relatively in line with historic averages. These providers operate with little acknowledgement and a per diem rate that is a fraction of the cost of incarceration. There is more that community providers could and should do and, with more appropriate funding and staffing levels commensurate with skills and training, I have every confidence that they could provide an even wider range of services and interventions that would better support safe and timely community reintegration.

- I recommend that the Minister of Public Safety promptly conduct an in-depth review of the community corrections sector with a view to considerably enhancing financial, technical and infrastructure supports. Funding for a reinvigorated community corrections model could be re-profiled from institutional corrections in direct proportion to declining warrants of committal and returning admissions, and the planned and gradual closures of redundant or archaic penitentiaries.

Before concluding, let me introduce a few non-pandemic-related investigations conducted this past year that are included in the body of my report. The Office undertook an investigation of uses of force involving incarcerated Black, Indigenous and Peoples of Colour (BIPOC), as well as other vulnerable populations (women, and individuals with a history of mental-health issues, self-injury and/or attempted suicide). In context of wider social movements and calls to action in Canada and elsewhere, and consistent with our oversight role to review all uses of force in corrections, this investigation takes a specific look at the intersection of racial representation and use-of-force incidents in Canadian federal penitentiaries. Other items reported here include:

- A Review of Women’s Corrections 30-Years since Creating Choices ;

- Preliminary Observations on Structured Intervention Units;

- An Investigation of the Use of Medical Isolation in Federal Corrections;

- An Investigation into a Suicide in a Maximum-Security Facility; and,

- A repeated request for Canada’s ratification of the Optional Protocol to the Convention against Torture.

These investigations are suggestive of the non-COVID-related systemic work that remains to be addressed, along with a range of commitments such as Patient Advocates, 24/7 nursing healthcare coverage in federal prisons, and combatting sexual coercion and violence behind bars, which have been delayed because of the pandemic.

To my staff, I say a heartfelt thank you for your commitment and dedication through these extraordinary times. May we soon celebrate better and brighter days together.

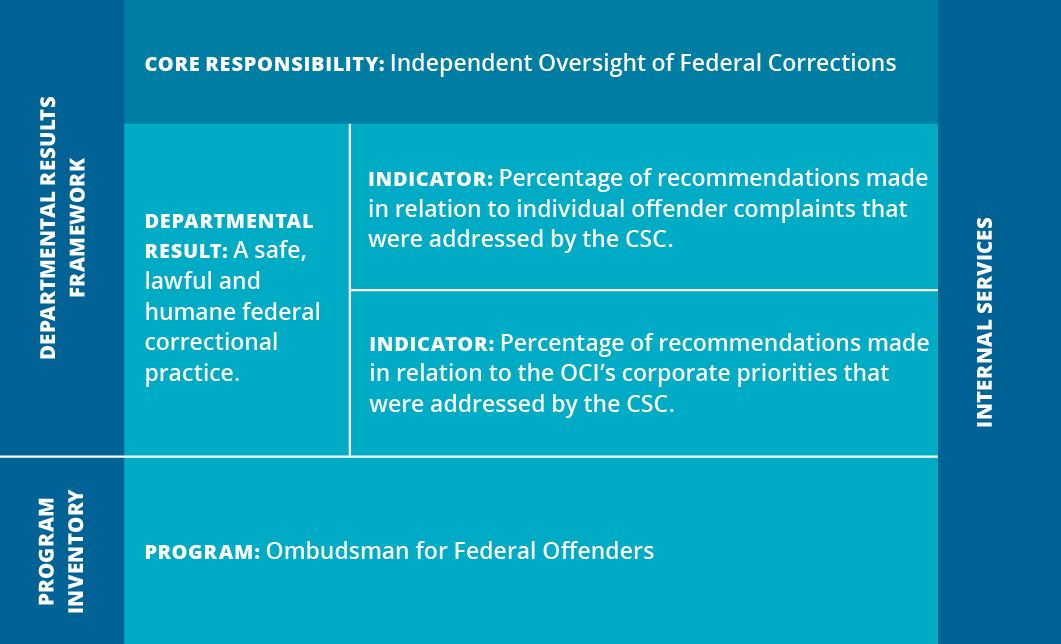

On a final note, my Office has been working with the Head of Federal Agencies to develop an alternative reporting framework that would streamline reporting obligations to reduce the burden for small departments and agencies. Our objective is to meet accountabilities for stewardship and transparency to Canadians by creating a single template or annex that could be added to an existing Annual Report. This is what I have done this year in an annex to this report to lead the way to ensure that the reporting burden is reduced for small agencies with limited resources.

Ivan Zinger, JD., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

REPORTING BURDEN FOR SMALL AND MICRO AGENCIES

Since my arrival at the Office of the Correctional Investigator back in 2004, I was struck by both the complexity of operating a small independent agency and the extent of the reporting burden imposed by central agencies and other Departments. When I was first appointed as Correctional Investigator of Canada four years ago, I took over the responsibilities of my predecessor as a member of the Heads of Federal Agencies Steering Committee (Steering Committee). In 2019, the Steering Committee established four Working Groups to address various challenges experienced by small and micro agencies. I volunteered to co-lead the Working Group on the Reporting Burden. It became apparent that there is a strong consensus among small and micro agencies that the reporting burden is overly bureaucratic and developed for all government organisations, which makes it very difficult to manage for small and micro organizations. The process goes beyond what is required to adhere to the reporting principles described in the Foundation Framework for Treasury Board Policies for SDA.

Binder containing the 2020-21 corporate reporting

requirements for the Office of the Correctional

Investigator.

To give some perspective, as a Deputy Head of a small agency, my Office has the same reporting burden than the very large Department that is subject to my independent oversight. While my agency has only 40 employees and an annual budget of $5.4M, I am required to issue almost same amount of reports, around 40 mandatory reports, than the Correctional Service of Canada, which has about 19,000 employees and a budget of more than $2.5B. Unlike CSC, my legislation also requires me to produce an annual report, which provides information about the work accomplished by my Office, for each fiscal year. I recognize that it is imperative to demonstrate and assure good stewardship of taxpayers’ money and sound management of human resources, but the lack of appreciation for the burden placed on small and micro agencies is striking.

The amount of red tape and unnecessary reporting requirements imposed on small and micro agencies hinder the delivery of my Office’s legal mandate. I currently have four full time employees and two casual employees assigned to Corporate Services. My Office also hires occasionally contractors to support its Corporate Services (e.g., develop a new case management system and redesign our cloud website). Those OCI employees are required to manage the following:

- Financial Management Services.

- Human Resource Management.

- Information Management.

- Information Technology.

- Management and Oversight.

- Material services.

- Acquisition Services.

- Real Property Services.

- Technical support for communication tools (Internet, Intranet).

In addition, they have to negotiate and manage a staggering 15 MOUs for various services with other Departments. This workload and the associated reporting burden are excessively high, moving away from the reporting efficiency principle and establishing a reporting framework where the cost to create and submit information should be kept to a minimum. In fact, I understand that a few small/micro agencies are now dedicating 30-50% of their personnel to Corporate Services. This is not the case for my Office but continuing with the existing staffing level without alleviating some tasks is becoming increasingly difficult.

The Heads of Small Agencies have raised the reporting burden issue with Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) for more than a decade now. Some small gains were made years ago, e.g., removing the requirement for the Management Accountability Framework and more recently, and to its credit, TBS initiated a process to assess which reporting requirements could be streamlined. TBS launched an initiative to renew its Information Collection Requirements Inventory. This database was designed to facilitate analysis of who is subject to requirements, the types of requirements, frequency of reporting and other important areas. Concurrently, TBS was hoping to uncover any duplication or redundancy of requirements, as well as identify best practices on mode of submission (e.g., digital platforms, other ways of electronic submission) that could be used to help ease burden related to these requirements. To date, TBS identified more than 140 collection requirements in 19 policy areas and offered only minor tweaks to the overall reporting burden. More importantly, out of the 40 reports prepared by OCI during 2020-21, TBS is only responsible for 40%, so any minor reduction has limited impact on current workload.

The Steering Committee is committed to continue to work towards reducing the current reporting burden and to engage TBS by participating in workshops and information exchanges. On a parallel stream, the Reporting Burden WG considered that an alternative approach may assist the GoC’s approach to reporting. The approach was simple, if there were no policy or legal constraints on existing reporting requirements, what would a report on all activities of a small agency look like? If the report was consistent with modern principles and best practices of accountability, openness, transparency, accessibility and sound management for a publicly funded agency, what basic information should be included?

With the financial assistance of the Steering Committee, the Reporting Burden WG retained the services of a consulting firm to review all 40 reports prepared by the OCI in the last fiscal year and develop a single streamlined report that would meet the following criteria:

- Open Data – those items that are being reported as a result of the open government priority;

- Transparency – those items that are being reported to address the government priority of transparency;

- Accessibility - those items being reported to facilitate parliamentarians’ access to reports and information;

- Compliance – those items being reported to comply with a policy or directive;

- Legislative – those items being reported as a result of a legislative requirement;

- Sound Management – those items being reported to demonstrate sound management to parliamentarians including oversight, stewardship, and accountability; and,

- Duplication – those items being reported under other requirements and not required to re-publish.

Unfortunately, the laws and regulations are so prescriptive and convoluted that compliance with the law was not achieved. This may in part explain why TBS cannot provide a larger reduction of the reporting burden of small agencies. If this alternative to reporting was going to be implemented, legislative and regulatory reforms would be required.

The report is in Annex D of my Annual Report and provides an overview of financial, human resources, planning and performance information about the operations of the OCI, as well as all reporting information to quasi-judicial bodies. This easily accessible report of only 12 pages summarizes required reporting information to fulfill OCI’s commitment to the public service value of transparency and as well communicates our management successes and challenges to Parliamentarians, Canadians, auditors, controllers, stakeholders and civil society at large. With the content of this year’s Annual Report, the readers can for the first time in a single document assess value for money and effectiveness of a small agency.

- I recommend that the President of Treasury Board recognize the reporting burden of small and micro agencies, and play a leadership role by developing a whole-of-government approach to alleviate this burden. Before full legal and regulatory reforms can be introduced, I recommend that TBS consider legal exemptions for eligible small and micro agencies to start reporting differently.

Executive Director’s Message

I was very happy to join the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI) as Executive Director and General Counsel in October 2020. Although I had big shoes to fill, I was enthusiastic for a new challenge, particularly in an area I was passionate about and for an organization with such an important mandate. I am grateful to work side by side with a dedicated, hard-working team of subject matter experts as I continue to appreciate the complexity of issues that arise in correctional settings.

As with all organizations, our focus over the past year was on accommodating work from home for all employees, in addition to ensuring continued delivery of our mandate: to provide the essential service of supporting the fair and humane treatment of persons serving federal sentences. Striving to continue to deliver the same quality of service, we were faced with challenges as we were not able to go into institutions to meet with prisoners face-to-face. That said, I am proud of how we were able to pivot to virtual visits so that we could still hear from incarcerated individuals on the range of issues they are experiencing. This could not have happened without the helpful collaboration of the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC). I am encouraged by the examples I see every day of the collaboration between OCI employees and CSC staff who work together to ensure that individuals in our correctional institutions are treated with dignity and respect, in accordance with the law and human rights principles.

My first task in joining the OCI was to get to know the team and to explore what they see as challenges and opportunities for the organization. I also wanted to ensure that the management team worked together as a united, high-functioning team. The tone for collaboration and healthy working habits starts at the top of the organization, creating a safe and healthy work environment for all employees.

In the last quarter of the year, we embarked on the first phase of a strategic planning exercise. With the COVID pandemic still upon us and in the midst of a third lockdown as I write this, we needed a sense of renewal for the organization. We committed to a theme for 2021 of Reconnecting, Re-energizing, and Re-engaging. We decided that we will focus on providing our employees with a workplace of choice by ensuring that: employees have the tools and training they need to do their work; roles and responsibilities for all employees are clear; our website is updated, reflecting our priorities and providing easier access to our information; and we engage in developing diversified well-being initiatives to best support our employees as this pandemic continues, and going forward.

In this next fiscal year, I hope we will be able to return to the workplace and to interact with each other in person. I also look forward to determining our priorities as well as developing a road map for identifying systemic issues and investigations. We will be developing an outreach and engagement strategy with our key stakeholders so that we can find ways to establish partnerships, a necessary and effective approach for a micro-agency with limited resources. We will also continue with phase 2 of our strategic planning exercise, developing a 3–5 year plan that will help us maximize the efficiencies we must find to operate within our allotted resources.

Finally, I look forward to continuing to support Canada’s Correctional Investigator, Dr. Ivan Zinger, as well as the entire team at the OCI, in delivering on our mandate to protect the human rights of those serving federal sentences.

Monette Maillet

Executive Director & General Counsel

Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada

National Updates and Significant Cases

This section summarizes policy issues or significant individual cases raised at the institutional and national levels in 2020-21. All of the issues and cases presented here were either the subject of discussions with institutional Wardens, an exchange of correspondence, or an agenda item in bilateral meetings involving the CSC Commissioner and myself, and our respective senior management teams. This section, then, serves to document progress in resolving issues of significance or concern.

No Progress on Sexual Coercion and Violence in Federal Corrections

My last annual report included a national investigation into sexual coercion and violence (SCV) in federal prisons. It found that the prevalence of SCV is largely unknown. It revealed considerable gaps in the Service’s approach to detecting, investigating and preventing sexually problematic behaviours behind bars. Further to this investigation, I issued five recommendations to improve how CSC responds to this pervasive yet underreported issue, among which was to introduce legislation immediately, similar to the United States’ Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) that was introduced in 2003. I also called upon the Minister of Public Safety to fund a national prevalence study to be conducted by fully independent experts. In response to the recommendations, the Minister committed that Public Safety would develop “a research plan, slated to begin in Fall 2020 to begin assessing SCV in federal corrections . . . An interim report on the work undertaken is set to be developed by Spring 2021.” In their response to the recommendations, the Service did not commit to any actionable change in approach. Footnote 3 It indicated only that it would support the work to be initiated by the Department. At the time this report was written, and after requests for updates from Public Safety, my office had yet to see a research plan or interim report indicating whether such work had been initiated.

Over the course of the reporting period, my office continued to receive complaints and concerns from incarcerated persons who have witnessed or experienced SCV. Despite the recommendations issued through our national investigation, this office has observed no appreciable difference in the way CSC prevents, detects, tracks or manages these types of incidents. We continue to hear cases of alleged perpetrators simply being shuffled around within and between institutions as the preferred method for “resolving” formal complaints of sexually problematic behaviours.

In their response to our recommendations, CSC noted, “The Service takes this issue very seriously. In order to ensure a safe and secure environment for all offenders in its care and custody, numerous measures have been put in place to ensure such acts are dealt with swiftly.” Unfortunately this has not been the case. There has been a disappointing lack of response and action subsequent to our recommendations. We know that the most vulnerable individuals are the ones most negatively affected by such inaction. I urge the Minister of Public Safety and the Commissioner of CSC once again to undertake the work required to address this issue effectively.

Continued Over-reliance on Use-of-Force Measures

Over the last reporting period, my use-of-force team brought to my attention a number of egregious incidents and recurring issues further to their reviews of use-of-force incidents in federal institutions. While many of these concerns are raised in the systemic investigation into uses of force I present later in this report, I want to highlight some of my office’s observations and interventions on individual cases.

Time and time again, we see examples of the general over-reliance on often unnecessary, and in some cases harmful, force interventions. My staff reviewed a number of incidents demonstrating unwarranted and dangerous use of direct-impact rounds on individuals who posed a low risk of harm to themselves or others. In one case, an individual was shot with an impact round from a 40-mm launcher near his left shoulder, just above his collarbone, dangerously close to an “emergency target zone.” This could have caused serious, and possibly life-threatening, injuries. After follow up from my staff, there was agreement from institutions that the use-of-force in some of these cases was inappropriate.

Similarly, my staff continue to see the over-use of inflammatory spray, which is problematic in and of itself and runs counter to the Engagement and Intervention Model (EIM). It is particularly concerning when used on individuals who have serious mental health concerns, or who are engaging in self-harm. We reviewed, for example, an incident involving a man certified under the province’s mental health act. Through the course of a healthcare procedure, facilitated by the Emergency Response Team (ERT), the individual became uncooperative. In response, the ERT used two separate bursts of pepper spray, handcuffs and other forms of physical handling and, at one point, a shield to kneel the patient over a cement bench. Clearly, more time, engagement, and verbal interventions should have been used with this man to de-escalate the situation, particularly given his mental health needs. Concerns regarding this incident were raised at all levels of the review. It was clear that the approach and techniques used (particularly the second burst of pepper spray and shield) were demonstrative of serious violations of use-of-force policies, run counter to numerous principles of the EIM, and revealed a number of health care deficiencies. Furthermore, this case and a number of others reviewed by my staff this year raise concerns regarding the role and responsibilities of ERTs. Inconsistent or non-existent use of verbal interventions or negotiations, inadequate assessment and reporting on the risk associated with the actions of incarcerated individuals, and the poor deployment and unreliable operation of cameras to record incidents, among other issues, suggest the need for greater oversight of ERT interventions.

Other incident reviews and interventions by my staff involving individuals with mental health concerns, or those actively engaged in self-harm or suicidal behaviours, continue to highlight my concerns regarding the need for more-effective and humane ways of responding to complex and troubling behaviours that stem from mental health issues. We continue to see examples of use-of-force incidents where the mental health elements at play are not adequately assessed, acknowledged, communicated or factored into the interventions. In turn, these are not reflected in the reporting and documenting of incidents. In my investigation into uses of force with BIPOC individuals and other vulnerable populations, I offer a number of recommendations to the Service to improve how it responds to incidents where force is often used, particularly those involving individuals with complex needs.

Use of Force Following an Attempt to Access the Prison’s Overdose Prevention Site

My office has previously reported on CSC’s harm-reduction programs such as the Prison Needle Exchange Program (PNEP) and the Overdose Prevention Sites (OPS), indicating that the way in which they were developed and implemented has limited enrollment. For example, PNEP kits can be seized if the syringe or needle is altered, missing or observed outside the kit. In other words, a zero-tolerance approach to drug possession in CSC facilities remains in effect. Drugs and drug paraphernalia (except CSC-issued PNEP kit and supplies) are still considered contraband items, subject to disciplinary measures. Not surprisingly, only a handful of prisoners participate in these programs that CSC rolled out nationally in spring 2019.

Over the reporting period, my office intervened on a use-of-force case that occurred following the denial by health care to allow an individual to access the OPS. After being denied access, the prisoner returned to his unit and locked himself in his cell. Correctional officers suspected he was carrying contraband most likely because he had tried to access the OPS. When officers arrived at his cell, they found the door window was covered. They opened the door and saw the prisoner snorting a white powder. They searched his cell, and seized drug paraphernalia, but they left him in his cell, where he covered his cell window again. Authorization was given to place him in an observation cell. When the escort team arrived, he did not cooperate with several direct orders. Physical handling, pain compliance and handcuffs were used to contain the situation. While the use of force may have ultimately been necessary given the resistance and lack of cooperation, the contradiction between the zero-tolerance approach to drug possession in prisons and access to harm-reduction measures such as PNEP and OPS created a situation that should never have occurred. Individuals accessing these services should be able to do so without the fear of reprisal. This would no doubt increase the number of those willing to participate. Other measures such as verbal interaction, engagement, counselling or observation may have resulted in a more positive outcome.

Lack of Appropriate Response Following a Recommendation Pertaining to a SHU Prisoner

Nearly two years ago, my Office highlighted the cases of three men who presented similar challenges for the Service. Throughout their incarceration, the men have spent significant time in segregation, been on mental health monitoring, and been transferred many times to other institutions. More importantly, they seem unable to cope with highly structured environments that trigger violent behaviours. Their symptoms and skill deficits appear to be specifically aggravated by heightened security measures. Nonetheless, the correctional response to these maladaptive behaviours is often to further restrict their conditions of confinement.

Strategies developed by institutional staff and mental health professionals have had limited impact on their behaviours and responsiveness to interventions. Recognizing that the management of the violent behaviours of these three men has been extremely challenging for both institutional staff and management, I recommended, under section 20 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , an external in-depth examination of the correctional profiles of these three men. At the time, CSC responded that it would conduct a clinical review of their care with a view to identifying any potential opportunities for improvement, including placement options.

Over the reporting period, my office again intervened on behalf of one of the three men being held at the Special Handling Unit (SHU), as his situation had once again become critical. It also appeared that—rather than accepting my recommendation to conduct an external examination of this man’s case—the Service conducted an internal exam. It concluded that, while not ideal, the SHU is an environment where the security of this man is best maintained. My office continues to monitor this case and follow up with the institution to ensure the best-possible case-management strategies are implemented for this individual.

Investigation into Uses of Force Involving Federally Incarcerated Black, Indigenous, Peoples of Colour (BIPOC) and Other Vulnerable Populations

Correctional authorities have a variety of tools and approaches to manage situations they assess as problematic, disruptive, or potentially unsafe. In addition to less-invasive or potentially less-harmful tactics, such as verbal interventions, uses of force allow correctional staff to employ physical actions (e.g., use of restraint equipment, dispensing inflammatory spray) to gain control or obtain the cooperation of individuals and resolve situations. The staff rely on these actions daily.

The use of force dates back as far as the prison system itself. It also has a long-standing history of criticism for its potential and well-documented misuse. More recently, the issue of force—specifically applied to individuals who are Black, Indigenous, or Peoples of Colour (BIPOC) — catapulted into the forefront of international public discourse in May 2020, following the murder of George Floyd while he was restrained by Minneapolis police officers. Less than a month later, in Canada, we saw video of the violent arrest and use of force on Athabasca Chipewyan Chief Allan Adam. Since then, mounting incidents have spurred worldwide protests calling for reforms to address systemic bias and the discriminatory application of harmful, and in some cases fatal, responses to incidents. In Canada, there has been widespread public outcry calling for law enforcement and criminal justice agencies to take a closer look at their policies and practices, such as the use of force, and how they are applied to BIPOC individuals, women, individuals with mental health issues, those with histories of self-injury, and other vulnerable populations.

In the wake of these events, and many others, there has been heightened social recognition that systemic bias exists, and has for generations, in most Canadian institutions. Corrections is no exception to this reality. In this context, it is important to recognize that within the most discretionary of policies and practices, such as when and how force is used, bias—implicit or otherwise—has considerable room to creep in.

Investigating uses of force is a key priority for my Office. Following a use-of-force intervention, CSC provides us with all incident-related documentation. This includes a use-of-force report, a copy of incident-related video recordings, checklists for health services, a review of the use of force, Officer Statement and Observation Reports, prisoners’ version of events, and an action plan to address deficiencies.

Part of the role my Office has taken on is not only to investigate individual complaints related to uses of force that are brought forward, but to review proactively all use-of-force incidents in federal prisons, and make recommendations to CSC when problems are identified. Furthermore, it is our responsibility to investigate concerns for which there is evidence of systemic issues in practices such as the use of force.

In previous reports, I have issued numerous recommendations calling for reductions to the use of force and the use of inflammatory agents, specifically with vulnerable populations. This office has conducted investigations into the role use of force has played in troubling individual cases, such as the deaths of Ashley Smith and Matthew Hines, and on specific groups of concern, such as women who chronically self-harm. Footnote 4 In keeping with this office’s persistent efforts to raise concerns regarding how force is used, we have also taken the current social calls-to-action as the impetus for an examination of how force is applied in federal corrections, specifically with BIPOC individuals, to advance discussions and solutions to the inequities these individuals face behind bars.

Purpose and Methods

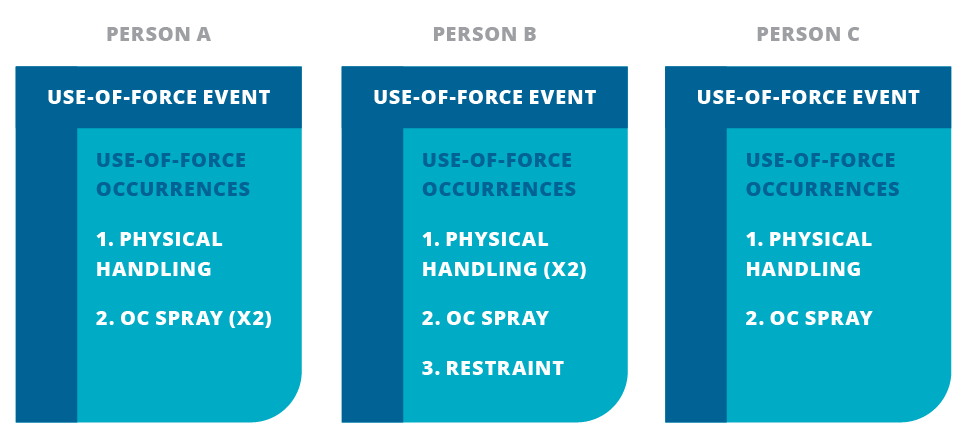

The present investigation examines use-of-force incidents, events and occurrences involving federally incarcerated BIPOC individuals, as well as incidents involving other potentially vulnerable populations. As illustrated in the diagram below, use-of-force incidents are cases, as determined and tracked by CSC, consisting of situations involving at least one individuals where force was applied at least once, documented, and tracked. A use-of-force event , as defined for the purposes of the present investigation, includes each use-of-force incident-by-person combination, which acknowledges that each person can be involved in more than one incident, and each incident can involve more than one person. Lastly, given that each person can experience more than one type and instance of force within and across incidents and events, a use-of-force occurrence , as defined for this investigation, constitutes each instance of force used on each individual within and across incidents and events.

Example: Use-of-Force Incident

The above is an example of one use-of-force incident involving three unique individuals. This incident represents three use-of-force events , and nine use-of-force occurrences.

Quantitative and qualitative data available for all use-of-force incidents from the last five years (April 2015 to October 2020) was extracted from CSC’s data warehouse system for analysis. We examined data at the individual and incident level overall, as well as by race and groups of interest. In addition to demographic information, we examined data on the frequency of incidents, reasons for uses of force, and types of force for each person involved in each incident.

This review explored these questions:

Who is involved in use-of-force incidents?

How are BIPOC individuals represented in use-of-force incidents?

What are the features of use-of-force incidents involving BIPOC?

Is use-of-force applied differently to BIPOC and non-BIPOC individuals?

How are other groups such as women, individuals with mental health issues, and histories of self-harm represented in use-of-force incidents?

WHAT IS USE-OF-FORCE IN FEDERAL CORRECTIONS?

Use-of-Force includes “any action by staff that is intended to obtain the cooperation and gain control of an inmate”. Use-of-force can be either spontaneous (i.e., an immediate intervention to a situation) or planned (e.g., staff are deployed through an intervention plan, deployment of the Emergency Response Team [ERT]).

According to CSC policy, use-of-force must be justifiable and used only as a last resort after verbal methods of negotiations have been attempted and proven unsuccessful or deemed “inappropriate”. Only under these circumstances may staff use force for the following reasons:

maintain compliance with institutional rules and regulations

maintain institutional safety and security

self-defence

in defence of others (staff or prisoners)

protection of property

The following are examples of uses of force that can be used by correctional staff. One or more types of force can be used in an incident.

physical handling or control (not including assistive or therapeutic touch)

use of a chemical or inflammatory agent, intentionally aimed at an individual or dispensed to gain compliance

non-routine use of restraint equipment

use of batons or other intermediary weapons

display or use of firearms

any direct intervention by the ERT

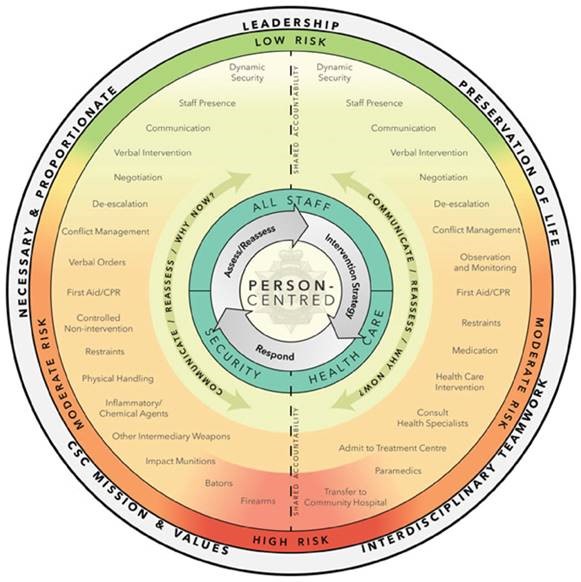

Engagement and Intervention Model (EIM)

In January 2018, CSC introduced the EIM to replace the Situation Management Model as a “risk-based model intended to guide staff in both security and health activities to prevent, respond to, and resolve incidents, using the most reasonable interventions”.

According to CSC, the intention of the EIM was to incorporate a more integrated, person-centered approach than the previous model, with a focus on the following five guiding principles:

preservation of life

interdisciplinary teamwork

CSC Mission & Values

necessary & proportionate

leadership

Source: CSC Hub Operational Procedures “About Use of force” and “Engagement and Intervention Model”.

Use-of-force Incidents

To provide context to the analysis by race, the following offers a broader description of the number of use-of-force incidents for the federal prison population overall, and a descriptive analysis of the documented reasons for uses of force and the types of force used in these incidents. Since 2015-16, there have been 9,633 documented use-of-force incidents. Despite the overall decrease in admissions to federal prisons and decreases in the prison population, the number of use-of-force incidents has increased steadily over the last five years.

Graph 1. Total Use-of-Force Incidents per Fiscal Year

While concerning, these increases are particularly troubling given that they coincide with the introduction of strategies aimed at reducing uses of force, most notably the Engagement and Intervention Model (EIM). The model was developed directly in response to my special report on the preventable death of Mathew Hines. Footnote 5 He died unexpectedly in federal custody in 2015 following a series of inappropriate use-of-force incidents at Dorchester Penitentiary. I issued ten concrete recommendations to CSC regarding urgent changes needed in response to incidents that too often result in the use of force, particularly those involving individuals exhibiting signs of physical or mental health distress. Consequently, in response to the third recommendation issued in Fatal Response , the EIM was developed in 2017 as a “situation-management model emphasizing the importance of non-physical and de-escalation responses to incidents” that theoretically should have resulted in more “person-centered approaches” to resolving incidents. In turn, these should have led to an observable decrease in use-of-force incidents.

Engagement and Intervention Model (2018)

This graphic represents CSC’s risk-based, person-centered Engagement and Intervention Model, and is used to assist staff with engagement and intervention strategies.

Reasons and Types of Force

We examined the reasons why force was used, and the types of force used. Overall, the majority of incidents were attributed to being “assault related,” such as assaults on inmates, and inmate fights (50%); “behaviour related,” such as disciplinary issues and disruptive behaviours (37%); and those related to self-injurious behaviours, such as self-inflicted injuries (8%). The rest involved contraband, property or other issues. It should be noted that CSC’s database, the Offender Management System (OMS), may not always capture the full context of incidents. In many cases, the reasons entered into the database are the most generic, or most “significant,” categories. Consequently, an incident that started, for example, as a self-harming incident that later involved the individual hitting a staff member might only be recorded as an “assault-related incident.” Therefore, we interpreted the reasons for force with caution. They may not have reflected the full picture of contributing behaviours.

Similarly, we examined the types of force used. Footnote 6 For ease of analysis, we organized the more-than-40 types of force represented in the data into five categories: Footnote 7

- Inflammatory Sprays (e.g., oleoresin capsicum [OC] spray, or “pepper spray”);

- Inflammatory Munitions (e.g., flameless or tactical grenades);

- Firearms (e.g., 9 mm pistol, shotgun);

- Non-inflammatory Devices/Options (e.g., batons, physical handling); and,

- Restraints (e.g., handcuffs, leg irons, body belts).

Overall, the far-and-away most-common types of force used were inflammatory sprays. They accounted for 42.3% of all force types in all incidents. This was followed by non-inflammatory options, used in a quarter of occurrences, followed by restraints (16.2%), inflammatory munitions (9.3%), and firearms (3.3%).

Similar to the perplexing findings showing the overall rates of force increasing over time, it is both concerning and disappointing that, despite the introduction of the EIM, staff still rely heavily on inflammatory sprays to “resolve” incidents. In fact, an analysis of types of force by fiscal year showed that use of inflammatory sprays was the most common type of force in each of the last five years, accounting for 40-47% of force types used each year. This practice is contradictory to the intent and letter of the EIM. It suggests that the shift anticipated in replacing the Situation Management Model with the EIM has not occurred. This office has previously recommended that CSC evaluate whether the EIM has had the intended impacts. It is clear by these metrics it has not.

- I recommend that CSC conduct an in-depth evaluation of the EIM with a view to implementing changes that will reduce the over-reliance on force options overall, particularly inflammatory sprays, and provide concrete strategies for adopting evidence-based, non-force options for resolving incidents.

Who is Involved in Use-of-force Incidents?

Between April 2015 and October 2020, the nearly nine-thousand documented use-of-force incidents that occurred in federal prisons involved 5,063 unique individuals. Footnote 8 For 4,952 of these, CSC had information on demographic characteristics including race. Table 1 provides a profile by self-identified racial group of all individuals involved in a use of force. Footnote 9 The vast majority were males (+90%), housed in medium- or maximum-security settings, and largely assessed as high-risk or high-need.

Table 1: Profile of Individuals Involved in Use-of-Force Incidents, by Race Groups

INDIGENOUS

(n = 1,932)WHITE

(n = 2,090)BLACK

(n = 609)POC

(n = 321)AVERAGE AGE

28.3

31.2

26.8

27.4

AVERAGE SENTENCE LENGTH

(YEARS)3.8

(SD=3.7)4.1

(SD=4.6)3.9

(SD=3.6)3.7

(SD=3.6)GENDER*

% Male

91.6

95.7

98.2

98.4

% Female

8.4

4.3

1.8

1.6

SECURITY LEVEL**

% Maximum

31.2

24.5

31.9

31.5

% Medium

30.9

30.2

32.3

33.3

% Minimum

1.8

1.6

1.6

1.2

% FIRST FERDERAL SENTENCE

58.6

53.0

71.6

80.7

RISK LEVEL

% High

77.3

74.1

76.0

68.2

% Medium

21.8

23.4

21.8

28.3

% Low

0.9

2.4

2.1

3.4

NEED LEVEL

% High

89.0

85.0

80.0

78.5

% Medium

10.6

13.6

17.6

19.6

% Low

0.5

1.2

1.6

1.9

Notes:

* There was no “other” gender category; however, 43 individuals had a gender considerations flag in OMS.

** There was a substantial amount of missing information on security level for each group; therefore, percentages do not add up to 100.Women and Use-of-Force

Over the five-year period, 824 incidents involved 271 unique women. Overall, women accounted for five percent of all individuals involved in uses of force, which is consistent with their proportion of the prison population. The majority of these incidents in facilities designated for women occurred in maximum security. Consistent with the prison population overall, most uses of force were related to assault (44.5%) or “behaviour-related” (27.2%). A much larger proportion of use-of-force incidents involving women, however, comprised incidents of self-injury (26.8% of all uses). For Indigenous women, nearly one-quarter (24.4%) of all incidents were in response to self-injurious behaviours.

BIPOC individuals accounted for more than two-thirds of all women involved in uses of force (67%), which was largely driven by the high numbers of Indigenous women. On average, Indigenous women accounted for 60% of all women involved in uses of force, despite accounting for approximately 40% of imprisoned women over the last five years.

When examining the use of force involving women, it is important to acknowledge the role of repeat or chronically involved individuals. As previously stated, individuals can be involved in more than one use-of-force incident. This is particularly salient for women. In fact, during the period under investigation, six women accounted for nearly one-third of all use-of-force incidents in women’s facilities. Moreover, one woman accounted for 11% of all incidents (89), and two women accounted for more than 50 incidents each. When the reasons for force were examined for all incidents involving these women, more than half were documented as occurring in response to self-injurious behaviours.

In the face of such findings, we need to ask ourselves: why are we expecting force options to effectively resolve mental health crises? Given that many of these women continue to self-harm and repeatedly experience force at the hands of correctional staff, clearly this approach is not working. If force should be used only when verbal negotiations have failed, this may be evidence that more-effective verbal negotiation and de-escalation techniques and training are needed. Staff need the right tools and training in order to respond effectively. And for the most chronically self-harming individuals, prisons may not be where they can or should receive the care they need. Meeting chronic self-harm with chronic use of force is an ineffective (and likely damaging) approach to working with people who have mental health needs. Moreover, attempts to extinguish temporarily the symptoms of otherwise possibly untreated underlying complex health issues is neither a productive nor humane correctional practice.

USE-OF-FORCE WITH OTHER VULNERABLE POPULATIONS

An examination of use-of-force incidents involving individuals with other vulnerabilities (i.e., history of self-injury and/or suicide attempts, mental health issues) was conducted for all incidents that took place between April 2015 and October 2020.

Individuals with a History of Self-injury and/or Suicide Attempts

Nearly half (46%) of all individuals involved in a use-of-force incident had a history of self-injury or attempted suicide.

12% of all use-of-force incidents were identified as being as a result of self-injurious behaviour.

More than one-quarter (27%) of all use-of-force incidents involving federally sentenced women were in response to self-injurious behaviour.

Inflammatory sprays were the most common type of force used for incidents documented as being initiated by self-injurious behaviour (i.e., used in 43% of self-injury incidents). In fact, that rate of use of inflammatory sprays for incidents of self-harm is the same as the overall rate of use for all incident types.

- I recommend CSC review and revise its policy and practice regarding use of inflammatory sprays when responding to incidents involving individuals who are self-harming or suicidal, with a view to reducing their use when responding to individuals who are experiencing mental health crises.

Individuals with Mental Health Concerns

Previous work by this office’s use-of-force review team found that, based on a review of individual files for a sample of nearly 2,000 use-of-force incidents, 41% of cases involved at least one individual with documented mental health concerns.

Given the lack of reliable administrative mental health indicators available, it is currently not possible to identify the proportion of individuals involved in uses of force who have mental health concerns.

- I recommend that CSC develop a reliable method for administratively tracking individuals with mental health concerns in order to identify how policies and practices, such as use-of-force, impact this particularly vulnerable population.

Note: An attempt was made to utilize the mental health “flag” data available in CSC’s Offender Management System (OMS); however, this information demonstrated numerous issues with data quality and reliability.

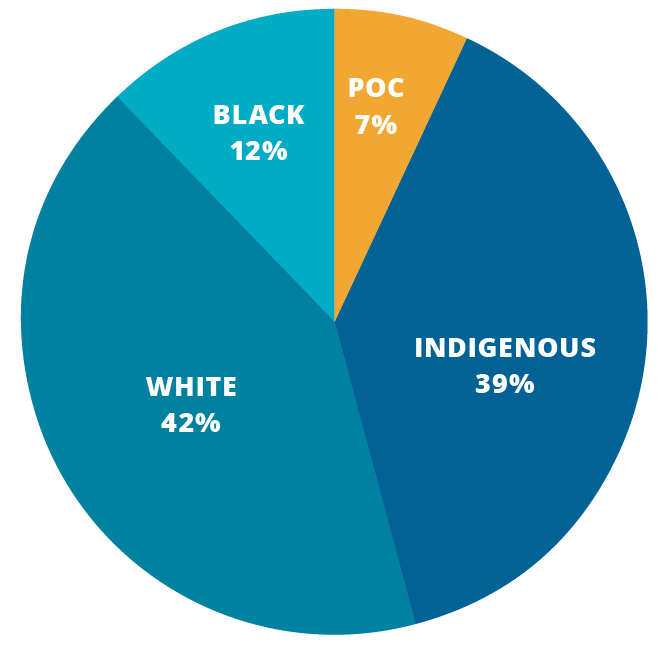

Race of individuals involved

in Use-of-Force incidents

April 2015 to October 2020

Individuals Involved in Use-of-Force Incidents by Racial Group

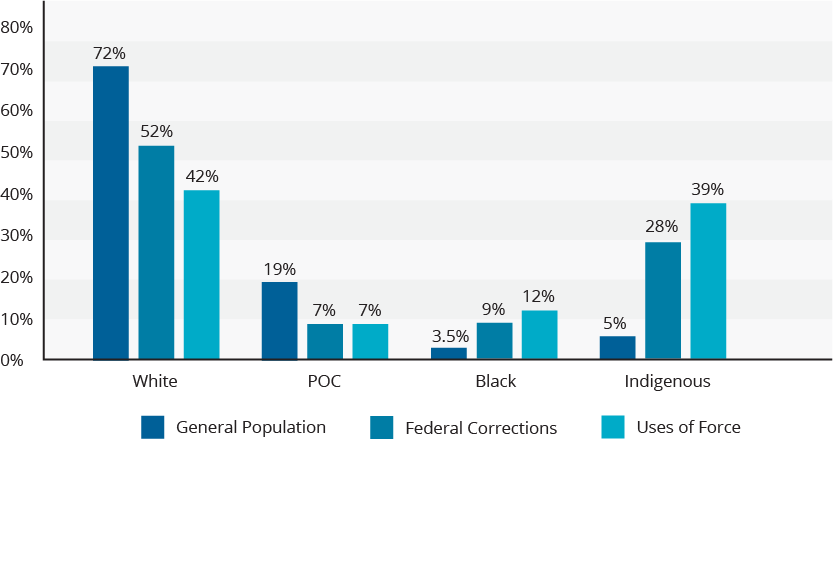

We examined the racial profile of individuals involved in use-of-force incidents. Despite accounting for 44% of the prison population, BIPOC individuals accounted for nearly 60% of all individuals involved in a use-of-force incident over the last five years. During the same period, White individuals accounted for 42% of all individuals involved in a use-of-force, while representing 52% of the prison population. Specifically, Indigenous individuals have been vastly over-represented, accounting for 39% of all individuals involved in uses of force, while comprising approximately 28% of the prison population over the same time. Black individuals were also over-represented, accounting for 12% while only representing 9% of the prison population.

Graph 2. Representation of White and BIPOC Individuals in the General Canadian Population, Federal Prison Population, and Use-of-Force Population

Taken together, Black and Indigenous peoples have accounted for 51% of individuals involved in uses of force since 2015 while representing 37% of the prison population and 8.5% of the Canadian population. Conversely, White individuals and Peoples of Colour were under-represented in the population of individuals involved in uses of force (42% and 6.5% respectively) compared to their representation in the prison population (52% and 7% respectively).

Use-of-force Events by Race

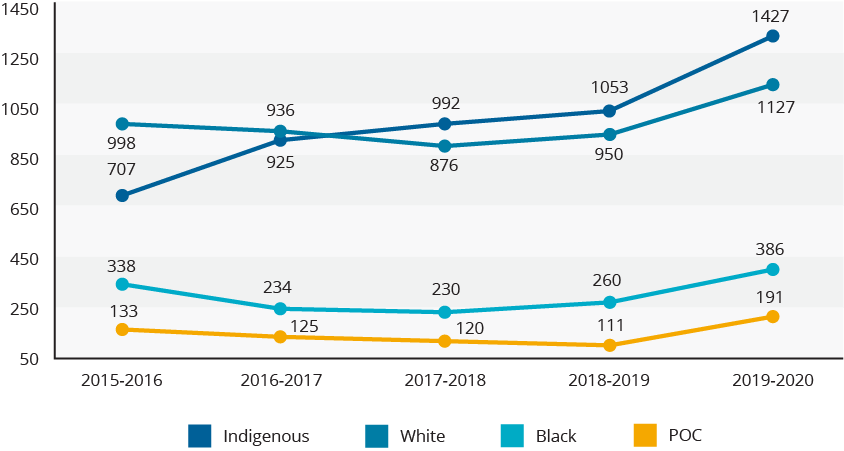

We also examined racial representation in incidents. An incident can, and often does, include more than one person, and therefore potentially more than one race group. We reviewed racial representation in use-of-force events (each unique incident-by-person combination). Graph 3 shows the total use-of-force events by racial group for the last five fiscal years. Footnote 10

Graph 3. Total Number of Use-of-Force Events by Race per Fiscal Year

Note: The data points across race groups within each fiscal year are not mutually exclusive and therefore the total of incidents per year does not add up to the total of incidents shown in Graph 1.

It is clear that use-of-force events have increasingly involved Indigenous individuals more than any other racial group, a trend that has been on the rise since 2015-16. In fact, in that year, the number of uses of force involving Indigenous individuals exceeded the number involving White individuals. It has continued to increase since. Not only are Indigenous individuals over-represented among unique persons involved in uses of force, they are vastly over-represented in use-of-force events.

Use-of-force Occurrences by Race

It was of interest to compare the average number of use-of-force incidents per person by racial group. Similarly, just as an individual could be involved in more than one use-of-force incident, an individual could be exposed to multiple occurrences (instances or applications of force) for each incident (see Table 2). For example, one individual could be involved in an incident where one occurrence and one type of force is used, such as one occurrence of physical handling. Another person could be involved in one incident but experienced three types of force and four occurrences of force, such as one occurrence of physical handling, one restraint, and two separate rounds of pepper spray.

As shown in Table 2, a comparison of the average number of use-of-force incidents and average number of force occurrences per person involved in a use-of-force incident for each race group revealed that Indigenous individuals experienced:

The highest average number of incidents per person compared to all other groups (more than three incidents per person on average);

The highest average number of occurrences of force compared to all other groups (i.e., more than five occurrences of force per person on average);

Higher average number of incidents (3.01 vs. 2.78) and occurrences of force (5.45 vs. 5.02) compared to the population average; and,

Significantly more incidents per person compared to White individuals (3.01 vs. 2.61).

Table 2: Average Number of Use-of-force Incidents and Average Number of Occurrences of Force per Person by Race Group

RACE GROUP

AVERAGE # INCIDENTS

PER PERSONAVERAGE # OF OCCURRENCES

OF FORCE PER PERSONINDIGENOUS

3.01

5.45

BLACK

2.78

5.43

WHITE

2.61

4.56

POC

2.53

4.71

POPULATION

AVERAGE2.78

5.02

While accounting for 12% of individuals involved in uses of force over the last five years, Black individuals had a higher average number of incidents per person (2.78) compared to White individuals and Peoples of Colour. It is also important to note that the average number of use-of-force occurrences for Black individuals (5.43) was very nearly as high as that for Indigenous individuals (5.45). While Black individuals are involved in a comparatively small number of incidents, their exposure to force is considerably denser per person compared to the other racial groups.

Reasons for and Types of Force by Racial Group

A brief examination of documented reasons for force demonstrated that while all race groups had generally the same rank order for the reasons attributed to the use-of-force incident, the following differences emerged:

Indigenous individuals and POC had a significantly higher proportion of assault-related incidents compared to White and Black individuals, and to the total population;

Indigenous and White individuals had significantly more uses of force attributed to self-injury compared to Black, POC and the total population; and,

Black and POC had a higher proportion of incidents attributed to contraband than White and Indigenous peoples, and the total population.

Table 3: Reasons for Uses of Force by Race Group and Total Population

INDIGENOUS

(n = 1,932)WHITE

(n = 2,090)BLACK

(n = 609)POC

(n = 321)TOTAL

POPULATION% ASSAULT-RELATED

53.3

45.7

49.1

56.9

50.0

% BEHAVIOUR-RELATED

34.7

39.7

41.5

31.9

37.3

% SELF-INJURY

8.1

9.7

2.9

3.0

7.8

% CONTRABAND

1.9

2.6

4.0

4.7

2.7

The Unique Role of Race in Uses of Force

The examination of use-of-force at the individual and incident levels consistently demonstrates the over-representation of Indigenous and Black individuals compared to their representation in the general population, prison population, and to other racial groups. Furthermore, it illustrates the overuse and density of force experienced specifically by Black and Indigenous individuals. While these results alone are compelling, the evidence does not tell us why over-representation exists. This in turn raises the question: could the greater use of force experienced by Black and Indigenous individuals be explained by the higher rates of these groups in higher security and risk groups? In other words, when taking into account the influence of risk level, security level, and other factors related to increased involvement in uses of force, is race uniquely related? More specifically, when making other important factors equal, does identifying as Indigenous or Black alone result in individuals being more likely to be involved in a use-of-force incident?

To explore this, two years of use-of-force data was examined, including all individuals who were in federal custody between 2018 and 2020. Individuals involved in at least one use-of-force incident were compared to those who were not involved in a use-of-force during that time (see Table 4). Information on risk level, security level, age, gender, and sentence length were obtained for each individual in order to analyze the relationship between race (Indigenous or Black, versus not) and involvement in a use-of-force incident.

Table 4: Comparison of Factors between Individuals Involved and Not Involved in Uses of Force Between 2018 and 2020

INVOLVED

(n = 2,967)NOT INVOLVED

(n = 24,283)% INDIGENOUS OR BLACK

53.5

33.8

AVERAGE AGE

29.9

37.1

AVERAGE SENTENCE LENGTH (YEARS)

4.0

3.2

GENDER

% Male

94.3

93.4

% Female

5.4

6.6

SECURITY LEVEL

% Maximum

35.4

3.5

% Medium

34.0

35.2

% Minimum

1.7

21.7

RISK LEVEL

% High

76

46.2

% Medium

21.8

37.3

% Low

1.8

13.4

Source: CSC Data Warehouse (February 2021).

Based on the data, the vast majority of all individuals incarcerated between 2018 and 2020 were males (93.5%), assessed as high or medium risk (49.5% and 35.6%, respectively), housed in medium security (35%), and serving an average sentence of 3.3 years (see Table 4). Footnote 11 Approximately 11% of all individuals were involved in at least one use-of-force incident, and 54% of all individuals involved in a use-of-force incident identified as Indigenous or Black. Footnote 12

A comparison and examination of the factors (race, age, sentence length, gender, security level, and risk level) demonstrated a significant relationship between each factor and involvement in a use-of-force incident. Specifically, being younger, having a longer sentence, being male, being higher security and risk, and identifying as Indigenous or Black were significantly associated with being involved in a use-of-force incident. Footnote 13

Next, we examined the relationship between race and involvement in a use-of-force. Footnote 14 This analysis revealed that identifying as Indigenous or Black made individuals significantly more likely to be involved in a use-of-force incident. Specifically, the odds of being involved were 2.5 times greater for an Indigenous or Black individual compared to someone who identified with another racial group. When the other factors were added to the model (age, gender, risk level, security level, and sentence length), all factors were significantly associated with involvement in a use-of-force. Importantly, the results indicate that the relationship between race and use-of-force, holding the effects of all five other factors constant, was still significantly associated with use-of-force involvement. Put differently, after controlling for the influence of age, risk, security level, gender, and sentence length on involvement in use-of-force, being Indigenous or Black was uniquely associated with increased odds of being involved in a use-of-force incident.

Other factors likely also play a role in explaining involvement in uses of force, but this finding tells us that the over-representation of Indigenous and Black individuals in use-of-force incidents cannot simply be explained by their greater proportions in higher risk or security groups, their younger age, or sentence length. The unique and significant role of race should be a wake-up call to the Service to take an earnest look at how use-of-force methods are applied and to whom they are applied the most. This finding provides compelling evidence to suggest that force is applied to Indigenous and Black individuals disproportionately, and possibly because of race, above and beyond more legitimate reasons. Put simply, race alone should not be a “risk factor” for exposure to uses of force.

- I recommend that CSC promptly develop an action plan in consultation with stakeholders to address the relationship between use-of-force and systemic racism against Indigenous and Black individuals and publicly report on actionable changes to policy and practice that will effectively reduce the over-representation of these groups among those exposed to uses of force.

Conclusion

The use of force in prisons is a powerful tool that has been afforded to correctional agencies. It can serve an important purpose within strict parameters and in limited circumstances. But, like many other practices that have ample room for discretionary use, the use of force has become a go-to method for correctional management. It is a method that is vulnerable to the influence of implicit and explicit bias.

Evidence of the over -use of force generally, and specifically with Black and Indigenous individuals, is irrefutable. This reality stands in disappointing contrast to the implementation of seemingly promising measures, such as the EIM, which had demonstrated some organizational will to move away from the over-reliance on force. The outcomes, however, are not only inconsistent with, but diametrically opposed to, the intentions of such measures.

There has been no better time or motivation than the current social climate for the Service to engage in self-reflection and examine its use-of-force policies and practices overall and with specific attention to Black and Indigenous peoples, as well as other vulnerable groups, who are disproportionately and most negatively affected.

A Review of Women’s Corrections 30-Years since Creating Choices

April 2020 marked the 30-year anniversary of Creating Choices . Footnote 15 Launched as a blueprint for women’s federal corrections in Canada, Creating Choices denoted the beginning of a correctional system that is recognized as woman-centered. The Commissioner of Corrections established the Task Force on Federally Sentenced Women (herein referred to as the Task Force) in 1989. The Task Force relied heavily on the lives, experiences and insight of federally sentenced women in examining the management practices for women in-custody, and in developing a plan and guidelines for future policies and interventions. The Task Force made short- and long-term recommendations that significantly changed women’s corrections. It enshrined five principles integral to a woman-centered approach to corrections: empowerment; meaningful and responsible choices; respect and dignity; supportive environment; and shared responsibility.

Structured Intervention Unit and Secure Unit yard

at Nova InstitutionSix years after the Task Force released its report, the Solicitor General of Canada released Honourable Louise Arbour’s report on her inquiry into events at the Prison for Women in Kingston, ON. Footnote 16 The report investigated incidents that took place between a group of incarcerated women and staff. The report issued 14 main recommendations, and served alongside Creating Choices as the political impetus for many of the operational and cultural changes in women’s federal corrections.

My Office has reported on women’s corrections in successive Annual Reports, noting many achievements, but also highlighting many problematic practices and areas where improvement was urgently needed. More than once, I have shown that an increased population of incarcerated women corresponds with an erosion of the key principles articulated in Creating Choices . The elevated number of incidents of self-injury, use of force, assaults (including sexual), fights, attempted suicides and interrupted overdoses among women point to a system that falls short of the principles and intentions embraced in Creating Choices . New issues have also arisen over the years that have further challenged the system and approaches to managing women’s corrections.

In 2020-21, the Office broadly examined the evolution of women’s corrections over the past three decades. We conducted confidential interviews with incarcerated women in each region, and CSC staff, to better inform our analysis and findings. Hearing directly from women who are serving time and staff who have worked within the Creating Choices framework is essential to better understanding the challenges and scope of the issues. We also reviewed academic literature, stakeholder resources and parliamentary reports.

The following analysis examines women’s corrections, set against the nine problems identified in Creating Choices . These include:

The Prison for Women is not adequate;

Prison for Women is over secure;

Programming is poor;

Women are isolated from their families;

The needs of Francophone women are not met;

The needs of Aboriginal women are not met;

Responsibility for federally sentenced women must be broadened;

Women need to be better integrated into the community; and,

Incarceration does not promote rehabilitation.

Highlights of the Main Findings

Creating Choices was a ground-breaking initiative that led to many improvements in women’s corrections; however, overall, little has changed for most federally incarcerated women. Footnote 17

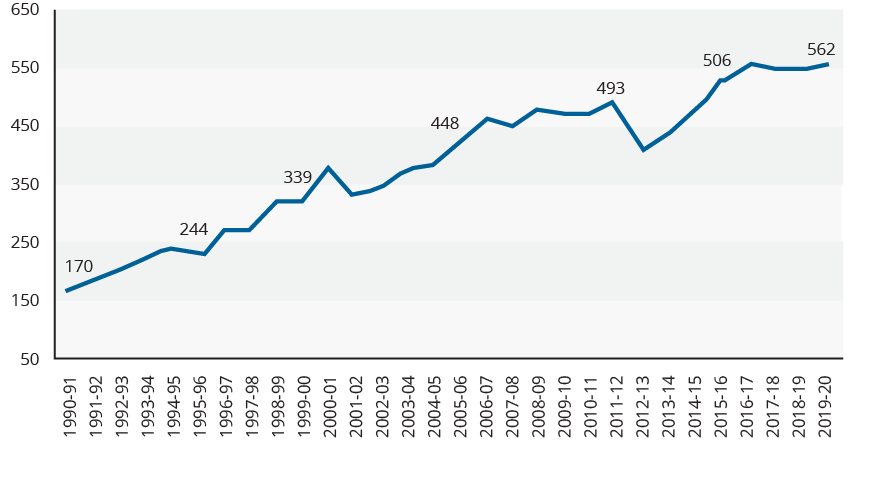

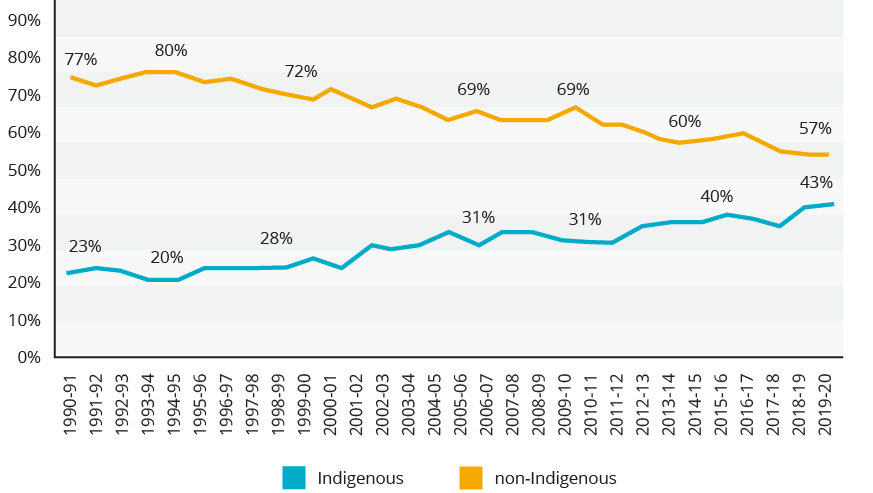

One of the most significant changes over the past thirty years has been the sheer increase in the number of federally sentenced women. Admissions to women’s federal correctional facilities more than tripled, from 170 in 1990-91 to 562 in 2019-20.

The composition of the population changed significantly. The population of federally sentenced Indigenous women increased by 73.8% over 30 years. Indigenous women comprise 43% of the federally sentenced women population, up from 23% in 1990-91.

Nearly all of the problems identified thirty years ago (inadequate infrastructure, over-securitization, lack of programming and services, poor community reintegration practices) remain significant areas of concern today, some have deteriorated even further and all are contributing factors to poor correctional outcomes for many women.

A security-driven approach continues to pervade nearly every aspect of women’s corrections, preventing CSC from realizing fully the vision in Creating Choices . Footnote 18

Programming, services, and interventions remain a substantial problem. While we heard from some women that they have had positive experiences in programs, correctional programming is not resulting in better community outcomes for many others. Indigenous women have limited access to specialized programming, and to Elders and Indigenous Liaison Officers. Job training for women is often grounded in gendered roles and expectations, offering few marketable skills.

Despite CSC research demonstrating that women granted temporary absences (TAs) experience lower unemployment and have fewer returns to custody, the use of TAs and work releases is limited. This prevents women from pursuing services and interventions outside prison that would offer opportunities better suited to their needs and interests.

Correctional practices that re-traumatize women (random strip searches), or a workplace culture that permits comments from staff that discriminate or bully women on the basis of their race, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, in no way contribute to a healing environment.

THE VOICES OF WOMEN

As part of our work for this chapter, we interviewed a number of women serving time. Below are their thoughts on the evolution of women’s corrections, challenges they face and the realization of Creating Choices .

On Empowerment and Choice:

“I have not felt that CSC is there to support us. Everything is a fight with management. Zero empowerment from the site, I have been disrespected by staff and witnessed staff disrespecting other inmates, I have submitted human rights complaints, discrimination/harassment complaints on behalf of other inmates. Decisions are taken in our case and they inform us of them, we are not consulted or part of the process.”

“Systemically we used to have more choices (Escorted Temporary Absences, Work Releases, even what we can get on the grocery list). It seems more restrictive now.”

“Escorted Temporary Absences/Work Releases abysmal. Been trying for 2.5 years but PO keeps changing things, now I need an updated Psych assessment and CP update. Frustrating.”

On Programs and Services: