Table of Contents

Correctional Investigator’s Message

National Systemic Investigations

Regional Treatment Centres in Crisis: The Erosion of Mental Health Care in Federal Corrections

Falling Through the Cracks: Federally Sentenced Individuals with Cognitive Deficits

Community’s Burden: The Discontinuity of Post-Release Mental Health Services

An Update on Therapeutic Ranges and Intermediate Mental Health Care

Assessing and Addressing Trauma in Federally Sentenced Women

Mental Health Needs and Services for Indigenous Peoples in Federal Corrections

Correctional Investigator’s Outlook for 2025-26

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

ANNEX A: Summary of Recommendations

Correctional Investigator’s Message

After much reflection, I have decided that this will be my final annual report. I intend to retire at the end of January 2026, concluding 30 years of public service—two years ahead of the end of my current five-year term. This timeline will allow for the public release of my final report in fall 2025 and provide the Government of Canada with sufficient time to appoint a qualified successor to lead the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI).

This was not an easy decision. It has been a privilege to serve at the OCI for the past 20 years, including the last nine as Correctional Investigator. As my predecessor, Howard Sapers, often reminded me, this is the dream job for anyone passionate about prison reform and human rights. Leading an independent prison ombudsman office and working with dedicated professionals to ensure that the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) upholds the rule of law and makes fair, accountable decisions in the administration of federal sentences has been both an extraordinary and fulfilling experience.

I have always been honoured to make evidence-based recommendations aimed at improving conditions of confinement and the treatment of federally incarcerated individuals and those serving the remainder of their federal sentence on conditional release. Speaking truth to power is a responsibility that I have never taken lightly. It is a necessary part of a healthy democracy. It is a challenging yet deeply rewarding role. However, holding the CSC accountable for mismanagement, unfair decisions, and human rights violations has not been without its toll.

I take immense pride in the work my team and I have accomplished in delivering world- class independent prison oversight and ombudsman services. I had the occasion to reflect on these accomplishments recently when our Office celebrated its 50th anniversary in 2023. It inspires a great sense of pride when I consider the cumulative years my team and I have tirelessly spent behind the prison walls and on the phone lines, listening and responding to concerns brought forward to our Office. On a systemic scale, we have conducted important and, in many cases, ground-breaking investigations into issues covering an array of topics and groups – ranging from issues affecting young adults to those who are aging and dying behind bars. Our ten-year update on Spirit Matters, an examination of Indigenous corrections, as well as the Experiences of Incarcerated Black Individuals, in particular, illustrate the value of this Office in tracking progress on important correctional issues over time and serve as a testament to our persistence in holding the CSC accountable to long-standing problems. During my tenure, my Office has boldly raised issues of fairness regarding the impacts of decision- making on the day-to-day lives of incarcerated persons, including the quality of prison food and the rising cost of living. We have also shown leadership in taking on more emerging issues in Canadian corrections, including sexual coercion and violence and the needs and rights of gender diverse prisoners. Our efforts in both investigating and issuing recommendations in these areas, among many others, have been to give a voice to those whose concerns often go unheard or unaddressed, to shine a light on the darkest places of corrections where inequity often finds itself, and importantly, to document accountability, so that these problems, many of which are well-known, can be prevented, curtailed, and resolved.

While we have achieved significant success in resolving individual complaints, many of our recommendations for systemic reform have too often been disregarded or dismissed by the CSC. Over the years, the Department of Public Safety and successive Ministers have also shown a reluctance to compel CSC to act on OCI recommendations, despite acknowledgment of the soundness of our findings. Despite its crucial mandate and a generous annual budget of $3.2 billion supported by 19,000 employees, federal corrections seemingly remains a low priority within the Public Safety portfolio, which also includes border security, policing, and national security. Given the increasingly complex global landscape, I expect that federal corrections will continue to receive limited attention within this broader public safety agenda. This is deeply unfortunate, as CSC is in urgent need of deep structural reform.

Canadians are not well served by a correctional system that is exceptionally costly and well-resourced by international standards, yet persistently fails to deliver on key correctional outcomes—particularly for Indigenous individuals in custody. While it is reassuring to know that the work of my Office has frequently informed court decisions, human rights complaints, class actions, and pre-trial settlements, such litigation could be avoided if CSC and the Government of Canada addressed long-standing issues more proactively. Meaningful reform would not only improve correctional outcomes and prevent human rights violations, but also reduce the financial, social, and human costs associated with litigation and recidivism.

As I approach my 60th birthday in January 2026, I recognize that it is time for new leadership at the OCI—someone with a fresh perspective and renewed energy who may succeed where I have faced obstacles. Although I will deeply miss this work, I look forward to retirement and spending more time with my family, as well as pursuing my passions for travel, sport motorcycling, downhill skiing, and scuba diving.

Knowing that this would be my final report, I chose to highlight an issue that has defined much of my career: access to and the quality of mental health care in federal corrections. My public service career actually began at CSC, where I completed my Ph.D. dissertation in the Psychology of Criminal Conduct with the CSC Research Division. That foundation, combined with early legal work focused on human rights in Corrections, has shaped my professional path and sustained my focus on the critical importance of mental health services for incarcerated individuals.

This year’s annual report therefore consists of findings from six national investigations into this very issue of access to and quality of mental health care for federally sentenced individuals, including the following areas:

- The overall purpose and functioning of CSC’s Regional Treatment Centres (RTCs).

- Approaches to identifying and addressing the needs of individuals with cognitive deficits.

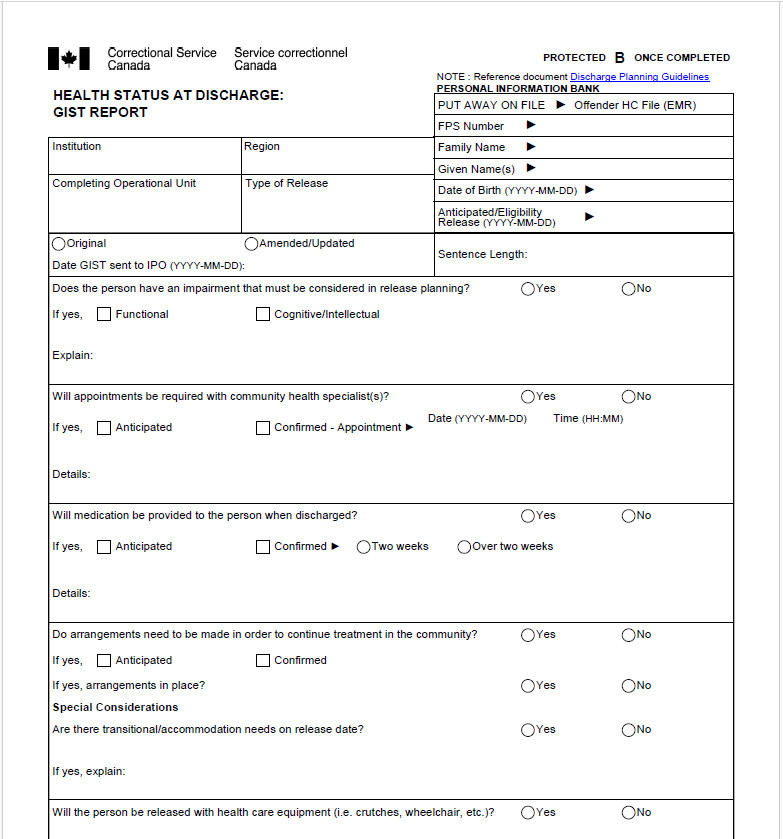

- Community discharge planning and the continuity of services for individuals with significant mental health issues.

- An update on Therapeutic Ranges and Intermediate Mental Health Care in federal prisons.

- Assessment and treatment of trauma for federally sentenced women.

- Culturally- and trauma-informed mental health and wellness services for Indigenous peoples in federal corrections.

For these investigations, the OCI conducted a grand total of 425 interviews with federally sentenced individuals, both in custody and on community release. We also conducted site visits and met with institutional and community staff, a variety of community-based stakeholders, Indigenous organizations, and provincial correctional authorities, among others. Furthermore, this year’s investigations were strengthened by partnerships and external expertise, including the Office of the Federal Ombudsperson for Victims of Crime and the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, to support our Office’s investigations into trauma-informed services for women and services for individuals with cognitive deficits, respectively.

There is no question that lack of access to timely, adequate, and appropriate mental health care is a human rights issue. After visiting all five RTCs, four of which are designated psychiatric hospitals, it is abundantly clear that CSC is fundamentally ill-equipped to provide long-term mental health care to individuals with serious mental illness—those experiencing acute psychiatric distress, suicidal ideation, and chronic self-injury.

The findings presented in this report reaffirm our long-standing position: CSC should not be in the business of delivering specialized long-term acute psychiatric care. In cases involving such serious mental illness, transfers to external, secure, community- based psychiatric hospitals are necessary. Consider this analogy: CSC routinely transfers individuals requiring complex physical care—such as chemotherapy or heart surgery—to external hospitals. It would be unthinkable to attempt such procedures in-house. Yet, when it comes to mental health, CSC continues to operate under the misguided belief that it can provide specialized psychiatric care internally.

Our latest findings underscore that RTCs can be best described as intermediate and geriatric care facilities, with limited emergency mental health capacity for acute cases. They should therefore be reprofiled and recognized as such. Individuals with acute and long-term psychiatric complex needs should be transferred, under section 29 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA), to specialized, external facilities capable of delivering the appropriate level and quality of care. Continuing to house these individuals in CSC-operated RTCs is not only ineffective and inappropriate—it is a clear violation of human rights and inconsistent with the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules) 1 .

Despite decades of investment, CSC remains unable to meet the complex mental health needs of this population. The announcement of a $1.3 billion replacement facility for RTC Atlantic (Shepody) is, in our view, a profound misallocation of resources. Rather than investing in another CSC in-house facility, the Government of Canada should have directed CSC to partner with provincial health systems to expand access to secure psychiatric beds in the community. The CSC could have funded enhanced bed capacity through provincial partnerships—an approach that would be more humane, cost-effective, and sustainable over the long term. The $1.3 billion allocated could cover the costs of such a model for decades to come.2 I urge the Government to reconsider its plans. The CSC is mandated to deliver correctional services, as well as health care services, which includes mental health care; however, they should not be engaged in the provision of acute psychiatric care. Similarly, the federal government should not assume responsibility for such specialized health care services. Instead, it should collaborate and coordinate with provincial health authorities to ensure that federally incarcerated individuals receive timely and appropriate mental health care in settings equipped to provide such care. Ironically, the CSC and the Government of Canada did not consult my Office on their intended investments. Consequently, absent from the plan was the most appropriate option to reform the delivery of acute mental health care and services in federal corrections: the transfer of seriously mentally ill patients to external, provincial psychiatric hospitals. This does not even appear to have been considered, despite being the option advocated not only by my Office, but by the Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights in its 2021 report entitled: Human Rights of Federally-Sentenced Persons. Even Bill S-230: Providing Alternatives to Isolation and Ensuring Oversight and Remedies in the Correctional System Act (Tona’s Law), promotes the approach of transferring individuals with disabling mental health issues to an external hospital.

The lack of transparency and failure to consult more broadly is indicative of how the CSC continues to prioritize what is best for the Service, and not what is best for those in their custody or supervision. The current plan is in violation of the Nelson Mandela Rules and only partnerships with provincial health care facilities will ensure proper care. The seriously mentally ill are patients first, and not inmates first. CSC’s approach has been the latter.

- I recommend that CSC’s RTCs be redefined and formally recognized as Intermediate Mental Health Care facilities, with limited capacity to manage emergency psychiatric cases. Individuals diagnosed with serious mental illness— those experiencing acute psychiatric crises, persistent suicidal ideation, or chronic self-harming behaviours requiring long-term psychiatric care—should be transferred to community-based psychiatric hospitals better suited to meet their needs.

- I recommend that CSC’s RTCs be redefined and formally recognized as Intermediate Mental Health Care facilities, with limited capacity to manage emergency psychiatric cases. Individuals diagnosed with serious mental illness— those experiencing acute psychiatric crises, persistent suicidal ideation, or chronic self-harming behaviours requiring long-term psychiatric care—should be transferred to community-based psychiatric hospitals better suited to meet their needs.

This year’s investigation into cognitive deficits is leading-edge in corrections, not only domestically but internationally, as it is an area that has been neglected. This investigation revealed that given such neglect, the prevalence of cognitive deficits is arguably unknown and likely underestimated. The consequences of such can be seen in the largely absent or ineffective approaches to screening, assessment, programming, and training for staff in relation to working with individuals with cognitive deficits. Vague and ill-fitting policies that do not adequately guide practice or match local realities or needs have consequentially led to stigma, safety issues, and challenges to daily living for those living with cognitive deficits in prison. These gaps and challenges place significant burdens on staff to seek creative solutions and opportunities to up-skill themselves, in some cases at their own expense, in order to meet these pressures and demands.

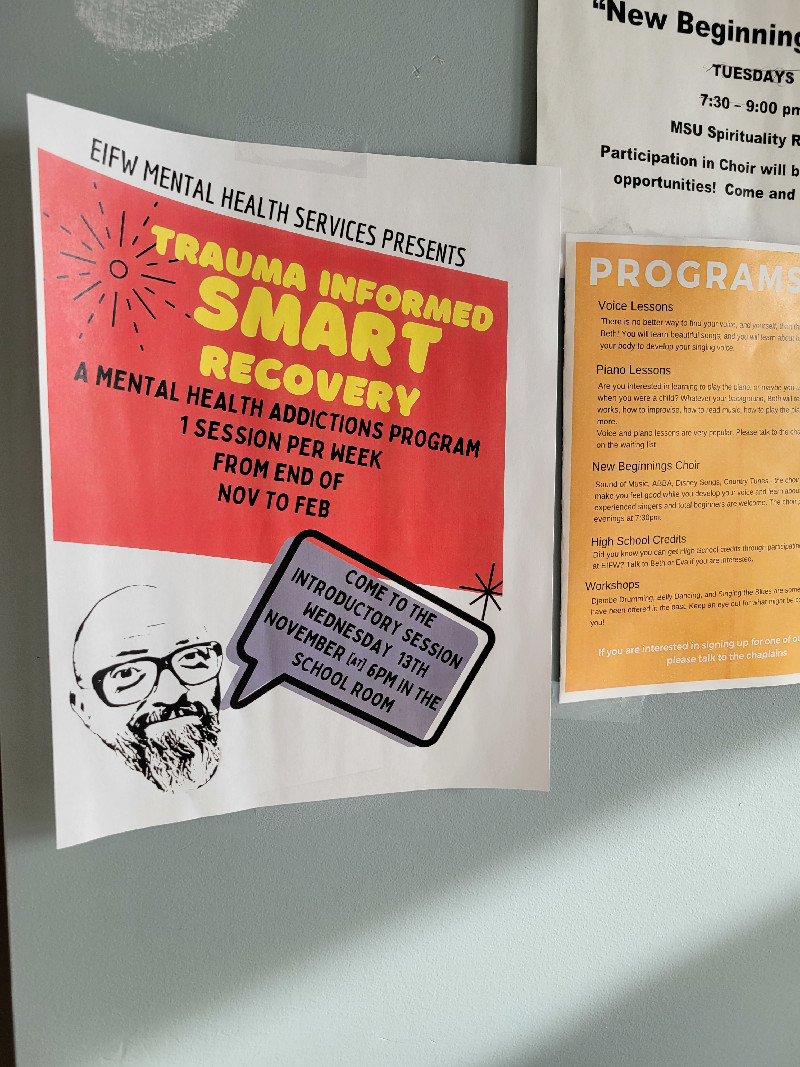

Also new ground for our Office, our investigation into trauma revealed that, despite nearly all incarcerated women having experienced some form of trauma in their lives, little is done in the way of screening and assessment, and few dedicated resources – particularly psychological supports – to help address the underlying causes of trauma- based responses. As was found in the other investigations, staff shared that they are inadequately prepared to effectively and safely work with women on the root causes of trauma. Relatedly, for Indigenous peoples serving federal sentences, trauma- and culturally-informed mental health and wellness services were found to be severely lacking, despite the significant needs of this population and their well-documented over-representation in the system. As this Office has called for previously and repeatedly, a broader decolonization of the prison system and a transfer of care to Indigenous, community-based organizations and individuals, is what is needed to make meaningful and lasting change.

Disappointingly, our look at progress made since our last reporting on Therapeutic Ranges, as well as the state-of-affairs in intermediate mental health care more broadly, revealed that many of the issues previously raised by this Office and the Service itself, remain and progress has seemingly stagnated. Our investigation into continuity of care and community discharge planning for individuals with serious mental health issues confirmed a similar, long-standing issue – the priority continues to be the resourcing of mainstream, custodial corrections, which has resulted in increased barriers and an overall erosion of mental health resources for those working in, and those being released to, the community.

While each investigation yielded subject-specific findings, given the unifying theme of mental health that runs through all six investigations, some cross-cutting findings and concerns also emerged, including:

- Weak, vague, outdated, and/or absent national policies have led to ineffective, confusing, and inconsistent direction and implementation of mental health services on the ground.

- Insufficient training provided to staff on how to work effectively and humanely with individuals with mental health issues (including those with cognitive deficits, age-related mental health issues, and/or trauma), has contributed to poor responsivity and quality of care in corrections.

- An absence of effective screening and assessment of mental health issues has created a domino effect of poor identification and access to services, thus excluding many who need such enhanced forms of care.

- Adapted and/or specialized options for programming, treatment, or opportunities for skill acquisition that would support preparations for successful release are inconsistent or unavailable.

- Prioritization of security measures, responses (including the use of force), and physical structures prevails over more dynamic, human-centred, and therapeutic forms of interaction and provision of care with individuals with mental health concerns, creating a fundamental conflict between health care and security staff, as well as between patients and staff.

Taken together, this report offers a comprehensive overview of the challenges CSC faces in delivering mental health care. Despite the criticisms contained herein, I wish to acknowledge the commitment and professionalism of CSC’s health care professionals and front-line staff, who do their best under extremely difficult conditions. During the course of our investigations, they provided invaluable and candid feedback.

Finally, I look forward to receiving CSC’s responses to my recommendations in a proper and transparent format, consistent with commitments made by two former Ministers of Public Safety. As the OCI has advocated for two decades, CSC’s responses should clearly indicate whether it agrees, agrees in part, or does not agree with each recommendation. Responses should be concise and should outline concrete actions to be taken, along with specific timelines. This would allow for the integration of CSC’s responses directly beneath each recommendation in the body of the report, as is standard practice across jurisdictions for ombudsman reports. This will also enable our Office to better track progress on an annual basis as well as formally report on responses to our recommendations as a departmental results indicator.

I acknowledge that CSC has not always had the authority to respond directly to some recommendations—for example, those requiring new legislation or additional funding. However, such cases are rare, and this report does not include any recommendations of that nature. In my professional opinion, CSC has the resources and the legislative authority, under the CCRA, to implement all of the recommendations contained in this year’s report. While some reallocation of existing resources may require support or approval from central agencies, I believe such prerequisites can be stated in CSC responses.

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

June 2025

Responses to Recommendations

To ensure clarity, transparency, and accountability, responses to the Office of the Correctional Investigator’s recommendations are embedded throughout this report. Each recommendation is followed by the agency or department’s selected response option and a supporting narrative outlining intended actions and timelines. The response options are defined as follows:

Accepted: The recommendation is fully agreed with and will be implemented as stated.

Accepted in-part: The recommendation is partially agreed with; some elements will be implemented while others will not.

Accepted in-principle: There is agreement with the overall recommendation and underlying conclusions; however, further action is required before the agency can commit to implementation (e.g., conducting consultation, securing new funding). This is therefore a conditional acceptance, acknowledging that further discussion and follow-up with the OCI is necessary.

Rejected: The recommendation is not agreed with and will not be implemented

- I recommend that CSC’s RTCs be redefined and formally recognized as intermediate mental health care facilities, with limited capacity to manage emergency psychiatric cases. Individuals diagnosed with serious mental illness—those experiencing acute psychiatric crises, persistent suicidal ideation, or chronic self-harming behaviours requiring long-term psychiatric care—should be transferred to community-based psychiatric hospitals better suited to meet their needs.

CSC's Response: REJECTED

The Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) acknowledges the need to ensure that inmates have access to the required health care services. and CSC currently has a health system and service delivery model to provide services that are matched to level of need.

To address the health needs of the inmate population, CSC Regional Treatment Centres (RTCs) provide a range of services at both the psychiatric in-patient and intermediate mental health levels of care. Psychiatric in-patient hospital care is provided to inmates who have serious mental health needs and require a hospital environment that provides access to 24-hour health care. Intermediate Mental Health Care is provided to inmates whose needs exceed the level of care provided through primary care at mainstream CSC institutions, based on an assessment of the inmate’s impairment in level of functioning.

Depending on the specific needs identified and level of treatment required, intermediate mental health care services are provided in select CSC institutions, or in RTCs. Currently, a significant proportion of RTC services are targeted to the provision of intermediate mental health care. CSC’s health services, including the RTCs, are accredited by Accreditation Canada, which is the same organization that accredits hospitals and other service providers in communities across the country.

To supplement CSC’s internal in-patient psychiatric capacity, CSC currently has a partnership with the lnstitut Philippe-Pinel de Montréal for the provision of in patient psychiatric care to men and women offenders, subject to meeting Pinel’s admission criteria. CSC will continue to engage with additional provincial psychiatric hospitals to supplement existing capacity for the provision of in patient psychiatric care. This engagement is done in acknowledgement of the limited capacity of provincial health care facilities to provide care to federal inmates, particularly in relation to their ability to admit federal inmates with complex mental health and security needs.

Despite this continued focus on engagement, to ensure that CSC has the capacity to meet its legislative mandate to provide essential health services to inmates, CSC must maintain a critical capacity to provide in-patient psychiatric care in RTCs. CSC is currently conducting a comprehensive review of its RTCs to provide a standardized baseline of service provision. This review will include a focus on ensuring that services provided align with CSC population health needs and reflect an appropriate mix of Psychiatric Hospital Care, Intermediate Mental Health Care, and short-term medical care.

Next Steps: CSC has initiated a review of Regional Treatment Centres to provide a standardized baseline of service provision.

Timeline: Fiscal year 2026-27

- I recommend that the Government of Canada/Minister of Public Safety reconsider its recent $1.3 billion investment in a replacement facility for RTC Atlantic (Shepody). Instead, efforts and funding should be redirected to support CSC in reallocating its current resources toward facilitating the transfer of individuals with serious mental illness to provincial psychiatric hospitals. This includes supporting the creation or expansion of bed space in provinces facing capacity constraints.

Public Safety's Response: REJECTED

The Health Centre of Excellence (HCoE) in Dorchester, New Brunswick, will be a modern, bilingual, purpose-built health care facility that will support CSC in advancing its patientcentered health care model and will set the standard for health care in federal corrections. It will increase bed capacity to better meet the health needs of an increasingly diverse and complex inmate population at both the in-patient and intermediate mental health levels of care. It will also support the provision of care to unique segments of the inmate population including those who have mobility issues; those requiring access to 24-hour care; women; and the Older Persons in Custody (OPIC) population. This facility is necessary in order to address the needs of inmates with mental health issues in the near and long term.

CSC engages with external hospitals to negotiate partnerships to enhance CSC’s capacity to treat individuals with more complex mental health needs. Admissions to external health care facilities are based on a standardized referral process, initiated by CSC, to address specific clinical needs. They are voluntary and require informed consent. It is important to note that CSC cannot compel external hospitals to enter into partnerships with CSC.

In 2024, CSC committed to engaging with forensic psychiatric hospitals to explore opportunities to establish Memorandums of Understanding (MOUs) for mental health assessment, treatment and inpatient care for CSC’s inmate patients. Health Services reached out to 11 external hospitals and all but one declined entering into a partnership for the provision of external psychiatric beds at that time. One external hospital indicated they would be open to future discussions around entering into such a partnership.

That said, the development of the HCoE is not being pursued to the exclusion of CSC’s ongoing partnership engagement. CSC Health Services continues to focus on partnerships in several key areas: access to community hospital beds, including forensic psychiatric beds; external health care services to meet specific health care needs; and specialized care for vulnerable subgroups (e.g., care for older inmates, care to gender diverse inmates).

CSC will continue to ensure that the highest standard of care, in line with community standards, is provided to individuals under CSC’s care.

Executive Director’s Message

It is with deep gratitude and optimism that I step into the role of Executive Director at the Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada. I am honoured to join a team of dedicated professionals who work tirelessly to uphold fairness and humane treatment in the federal correctional system.

I extend my heartfelt thanks to our outgoing Executive Director, Monette Maillet, for her exceptional leadership. Her contributions have left a lasting legacy—from stabilizing the workforce, to modernizing systems and reducing backlog, to guiding the Office toward compliance with international standards and strengthening our ability to respond to the needs of those we serve. Her leadership has had a lasting and meaningful impact on this Office.

As a human rights lawyer, I have spent my career advancing reconciliation, justice, equity, and accountability. My experience has taught me that public safety and human rights are not at odds, they are in fact deeply interconnected. I am excited to work alongside this incredible team, bringing our shared knowledge and diverse experiences together to strengthen our efforts and ensure that individuals serving federal sentences are treated with dignity, fairness, and humanity. I am proud to highlight some of their achievements.

Over the past year, our Office received 4,352 complaints from federally sentenced individuals—each one representing a voice that deserves to be heard and a concern that matters. We spent more than 96,000 minutes on the phone lines and 433 days inside correctional facilities—efforts that reflect the compassion and dedication of our team, and the importance of being present, listening, and responding in meaningful ways.

In response to the evolving needs of those we serve, the Office has made important strides this year. Using the Lean method, we improved the efficiency of our early resolution and operational processes, allowing us to respond more quickly and effectively. The Office has developed dedicated investigative teams that prioritize tandem institutional visits to ensure consistency and enhanced oversight, with a goal of developing specialized knowledge, strong collaboration, and higher quality operational outcomes. Finally, we introduced a triage process for use of force cases to streamline workflow and prioritize the most urgent and critical reviews with efficient resource allocation.

The Office has expanded our engagement both domestically and internationally sharing best practices, learning from others, and building relationships that help enhance correctional oversight around the world. Our work with Indigenous rightsholders and organizations has been especially important, guiding the ongoing development of a dedicated Indigenous Strategy that reflects our deep commitment to reconciliation and to addressing the systemic inequities faced by Indigenous people in federal custody. We have participated in key conversations at parliamentary committees and conferences, contributing to critical discussions that shape Canada’s criminal justice policies and influence how the rights of incarcerated individuals are protected.

When I first joined the OCI, I met with each employee to get their perspectives on what was going well in the office and where we needed to improve. I was grateful to receive open, honest, and thoughtful feedback.

At a very high level what I heard was that our employees appreciated the trust the office has in them to effectively do their work. They also appreciate the flexibility and understanding given to employees by their managers. The mandate of the organization is a critical one that gives them a sense of purpose. Many feel that there is good collegiality on the team and that they can have open and honest conversations with each other and with management. Employees also appreciate management having an open-door policy.

Some of the challenges I heard included that the volume and challenging content of the work has put some positions at higher risk of burn out. In addition, as this is a micro agency, opportunities for promotion are limited and employees felt that too little attention was invested in their growth and career progression. I also heard there is a need for better internal communication, consistent onboarding practices, job-specific training, and more open competition for jobs. It became clear that this has been a time of significant transition for the organization which saw a turnover in 50% of the executive team, either through retirements or departures. In addition, the Correctional Investigator shared his intention to retire within the next fiscal year. Our employees, like others in the public service, have increased their presence in the office while consideration has been given to their travel, time spent in institutions, and accommodation needs.

The Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) from 2024 echoes this feedback. This is feedback we take very seriously. After briefing the Correctional Investigator, we agreed that we will seek an external resource to support the organization in comprehensively addressing the concerns raised both in my interviews and through the PSES. This will ensure that we have a sound action plan with reasonable timeframes to effect organizational change prior to the departure of the current Correctional Investigator.

Since fully assuming the role of Executive Director in mid-January 2025, the Correctional Investigator, the management team, and I have initiated several changes in response to what we have heard. Performance agreements have been completed for the team and four advertised selection processes were launched. At least two of these processes included external board members as well as external human resources advice. We have begun the creation of a consolidated procedures manual to ensure that all operational staff have access to up-to-date comprehensive information that will support them in their work. The Corporate team is now fully staffed, and we have launched an exercise to renew our human resources policies. New employees are working in teams or are being paired with a “buddy” to ensure they have a dedicated resource to support them in addition to their manager and other colleagues. We are continuing to authorize two investigators to travel to institutions together as frequently as possible in compliance with international standards, but also to support their wellbeing given the challenging work that they do. In addition, we will be launching an Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA) committee in the coming months as well as a self-declaration campaign. We will work with a consultant to help develop an Information Management Architecture, which will pave the way to a new document management system to help address a number of irritants in how we organize, store, and access all of our documents. We have also staffed a dedicated Communications position to improve both our internal and external communications with staff and stakeholders, as well as support more proactive and consistent outreach and engagement.

The OCI remains committed to making this a great workplace with concrete action in a reasonable time.

As we prepare for a leadership transition in the year ahead, I want to extend my sincere congratulations to Dr. Ivan Zinger on his exceptional career with the OCI and the federal public service. I look forward to continuing to work with him and learn from him during this time of change and growth. This moment presents a valuable opportunity to reflect, renew, and build on the strong foundation that has been laid, as we refine our investigative, policy, and research work and continue to move our mandate forward.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to build on our collective strengths and to help shape a more humane, accountable correctional system.

None of this progress would be possible without the incredible work of our team. Whether in corporate services, early resolution, operations, policy and research, our specialized portfolios, or our use of force review team—every individual here plays a vital role. Your knowledge, your integrity, and your commitment are what give this Office its strength.

Valerie Phillips

Executive Director

National Systemic Investigations

Regional Treatment Centres in Crisis: The Erosion of Mental Health Care in Federal Corrections

In the Office’s 2023-24 Annual Report, we examined the circumstances that led to the tragic death of Mr. Stéphane Bissonnette, a 39-year-old man who, in December 2021, died in an observation cell while on modified suicide watch at the Regional Treatment Centre (RTC) Millhaven. In addition to spending significant lengths of his sentence in administrative segregation in maximum-security facilities, Mr. Bissonnette had also been subject to various placements in Regional Treatment Centres across the country.

The investigation into Mr. Bissonnette’s death revealed a significant degree of dysfunction at RTC Millhaven including structural, operational, and policy deficiencies. The Office identified a multitude of systemic issues related to his time at multiple RTCs, the events leading to his death, the National Board of Investigation (NBOI) which was subsequently convened, and the findings stemming from the NBOI itself. The need to comprehensively examine the functioning of these facilities on a broader, more systemic level was apparent.

Background

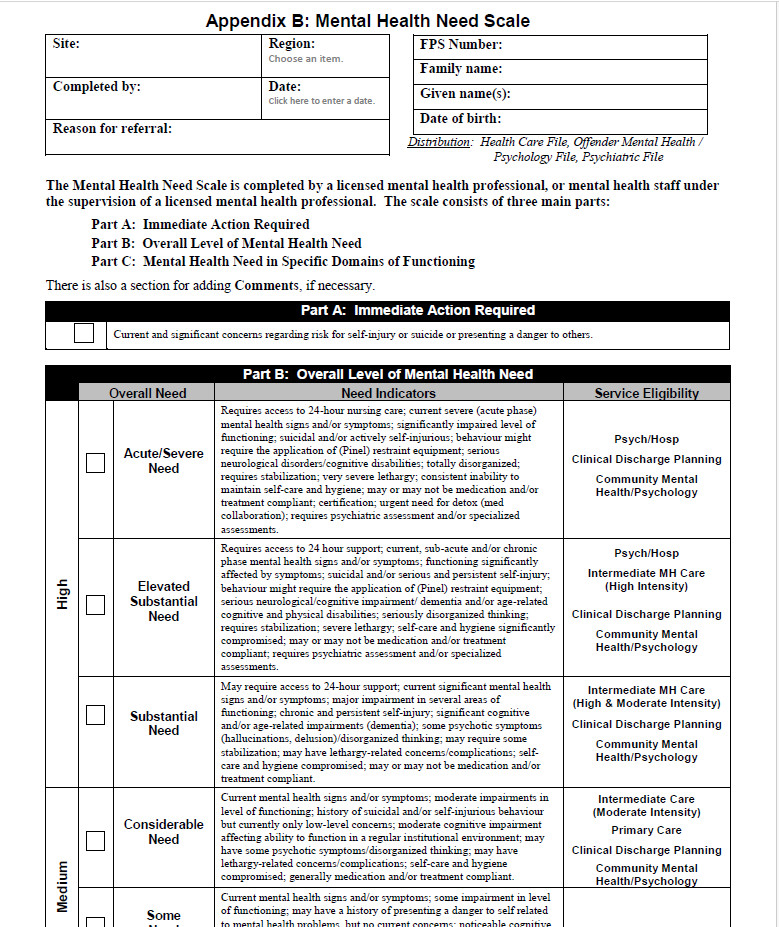

Under the Correctional and Conditional Release Act (CCRA), CSC is required to provide federally sentenced individuals with essential health care and reasonable access to non- essential health and mental health care that will contribute to the individual’s rehabilitation and successful reintegration into the community. When care is provided, the CCRA stipulates that the Service shall promote decision-making that is based on the appropriate medical, dental, and mental health care criteria. In efforts to meet this obligation, CSC operates five Regional Treatment Centres (RTCs) across Canada that provide clinical assessment and inpatient treatment for federally sentenced individuals with serious acute and/or chronic mental health conditions. The primary role of RTCs is to provide specialized services of a “time-limited nature” to stabilize individuals with the expectation that patients, where appropriate, will transition back to their ‘parent’ institution with a plan for continuity of care.

Treatment centres present a unique dynamic in that they are ‘hybrid’ facilities – psychiatric hospitals guided in part by provincial health legislation, operating within a federal penitentiary setting subject to the CCRA. All treatment centres, except for the Regional Psychiatric Centre (RPC) in the Prairie region, are co-located within larger penitentiary sites. Some of these facilities are subsumed within existing penitentiaries, while other treatment centres are found in repurposed or converted buildings.

Table 1. List of Regional Treatment Centres (RTCs) with Rated Bed Capacities and Snapshot of Actual Counts (2024)

| RTC and Location | Co-located Institution | Rated Capacity | Actual Count |

|---|---|---|---|

|

RTC Ontario which includes:

RTC Bath RTC Millhaven |

Bath Institution Millhaven Institution |

36 90 |

36 89 |

| RTC Pacific (Abbotsford, BC) | Pacific Institution | 168 | 129 |

| Regional Psychiatric Centre (Saskatoon, SK) | N/A – Standalone Facility |

184 men /

20 women |

145 men /

9 women |

| Regional Mental Health Centre (Sainte-Anne-des-Plaines, QC) | Archambault Institution | 119 | 83 |

| Shepody Healing Centre (Dorchester, NB) | Dorchester Institution | 38 | 42 |

| Total |

635 men /

20 women |

524 men /

9 women |

Source. Retrieved from the Corporate Reporting System Modernized (CRS-M) on July 11, 2024. 3

In addition to these facilities, the Institut national de psychiatrie légale Philippe-Pinel (INPLPP) in Montréal, Quebec, has five CSC funded beds for men and 15 beds for women, bringing the total capacity to 640 beds and 35 beds, for men and women respectively. As will be discussed later in this section, many of these beds are occupied by geriatric patients or individuals with disabilities and those requiring intermediate care, who may not meet CSC’s criteria for a psychiatric bed.

Nominally, the RTCs fall under CSC’s Health Services Sector, and are headed by an Executive Director. In practice, the Executive Directors work closely with and are accountable to the Warden (at co-located sites), as well as Health Services (at the Regional and National levels), resulting in a confusing organizational structure. In policy, the RTCs are classified as multi-level security facilities, meaning that patients assigned an Offender Security Level (OSL) consistent with minimum, medium, or maximum security can all be housed in the same facility. According to Commissioner’s Directive (CD) 706 - Classification of Institutions, RTC security measures should be dependent on the individual’s classification while the patient’s time at RTC should reflect their security level and be in compliance with their correctional and treatment plans.

Designation as Psychiatric Facilities

All but one of the RTC units are “designated” psychiatric facilities. While specific definitions may vary, designation refers to the formal recognition of a facility as a psychiatric or mental health centre by the provincial government where the RTC is located. In some provinces, the Minister of Health holds the legislative authority to designate psychiatric or mental health facilities while the required services for designation can vary by province as well (e.g., one or more of the following services may be needed to qualify: registered psychiatric nursing, emergency stabilization, observation, rehabilitation services, inpatient or outpatient care, etc.). This variation in requirements raises concerns about consistency in mental health care quality across provinces, as some jurisdictions may have higher service expectations. An outlier, the Regional Mental Health Centre (RMHC) at Archambault Institution is not designated as a “hospital” under provincial legislation due to its legislative framework, a notable difference that highlights potential legal and administrative gaps that affect the relation between federal institutions and provincial mental health care systems.

While CSC could not provide an exact date when individual RTCs were designated in accordance with their respective provincial legislation, it was suggested that this occurred in response to the enactment of the Canada Health Act (1984), which ensured all eligible residents of Canada had access to insured health services without financial or other barriers, and under which federally sentenced individuals were determined to be ineligible. The Penitentiary Act, which previously covered health service delivery for prisoners, was replaced with the enactment of the CCRA in 1992, leading to an effort by the Service to keep parity with community standards and a new focus on centralized health and mental health services.

When seeking designation for a particular facility, CSC must generally apply to the respective provincial ministry of health. Individual ministries may look at elements such as infrastructure, staffing models, location, and how care is delivered. The application process is ordinarily conducted by the Regional Director, Health Services (RDHS) for each region and signed off by the Commissioner.

Notably, once a province designates a particular facility, there are no further evaluations or ongoing mechanisms to ensure adequate services are being provided to maintain designation. Treatment Centres do not have to re-apply to maintain their designation and will, in virtually all cases, maintain this until such time as a facility needs to physically move. For example, following the closure of the treatment centre found within Kingston Penitentiary, a designated Schedule 1 facility 4, and the subsequent displacement of patients until their eventual transfer to Bath and Millhaven Institutions (RTC ON), reapplication to the Ontario Ministry of Health was required. CSC staff advised that, as a result, accreditation is the mechanism most often relied upon to measure adherence to health standards within these facilities. Even in the case of tribunals such as the Consent Capacity Board in Ontario, for example, ruling against the certification of patients to receive care against their will, designation of individual facilities is not called into question.

Designation aside, the health services provided by CSC, including mental health care, are subject to accreditation by Accreditation Canada, an independent non-profit organization responsible for ensuring that these services meet certain standards of quality and safety. These standards, created in consultation with a diverse range of representatives, are developed by the Health Standards Organization (HSO), also a non-profit entity, and form the foundation for the accreditation process. CSC has commissioned the HSO to develop a National Standard of Canada for correctional institutions, which has been subsequently integrated into its accreditation program. According to HSO, the new standard, HSO 34008:2018 (E) Correctional Services of Canada Health Services, is specifically designed to address the needs of federal correctional institutions, recognizing the link between the wellbeing of incarcerated individuals and their human rights (HSO, 2024). 5

Generally, meeting accreditation standards is a key benchmark for hospitals and psychiatric facilities to ensure that deficiencies are identified and services provided to patients are consistent with professional standards, with an aim of continuous improvement.

To dismiss prisoners’ legitimate criticisms about limited access and quality of mental health care, the CSC has repeatedly used accreditation as a shield to respond to such concerns. Accreditation is important but should never be used as a shield – accreditation does not, for example, set standards on the appropriate patient/mental health professional’s practice and minimal level of mental health care. CSC Communications should never use accreditation to dismiss legitimate concerns.

RTC Population Profile

In a 2024 profile of mental health care patients 6, CSC provided the following demographic information for the 498 individual patients in custody at all RTCs (see Table 2). According to their data, the vast majority of RTC patients are men (98%), more than one third identify as Indigenous (34%), and the majority are classified as medium or maximum security (62% and 24%, respectively). As for diagnoses, 86% of individuals at an RTC had at least one mental health diagnosis, with the most common being schizophrenia (46%), followed by depression (15%), anxiety disorder, and opioid use disorders (12% respectively).

Table 2. Demographic and Diagnostic Profile of RTC Patients (n = 498)

| # | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 487 | 98 |

| Female | 11 | 2 |

| Race | ||

| White | 248 | 50 |

| Indigenous | 167 | 34 |

| Black | 32 | 6 |

| Other | 51 | 10 |

| Security Level | ||

| Maximum | 118 | 24 |

| Medium | 310 | 62 |

| Minimum | 45 | 9 |

| No rating | 25 | 5 |

| Mental Health Diagnoses | ||

| Schizophrenia | 227 | 46 |

| Depression | 77 | 15 |

| Anxiety disorder | 59 | 12 |

| Opioid Use Disorder | 58 | 12 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 40 | 8 |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder | 40 | 8 |

| Dementia | 26 | 5 |

| Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder | 21 | 4 |

Note. The numbers for diagnoses exceed the total as individuals may have more than one diagnosis.

Previous Reporting on RTCs

While the Office had not examined RTCs at an in-depth level prior to the issues that emerged from the Bissonnette investigation, we had previously raised several concerns regarding their overall purpose and admission criteria more than a decade ago.7 In more recent years, the Office has flagged issues regarding excessive use of force at RTCs, recommending a review of security practices and protocols to ensure a more supportive clinical environment. Most notably, the Office’s 2017-2018 Annual Report provided a summary of the findings from an independent expert review conducted by Forensic Psychiatrist, Dr. John Bradford.8 Some of Dr. Bradford’s findings included concerns regarding a lack of adequate training for staff working with forensic patients, a complete disregard for the selection of appropriate correctional staff to work in this type of environment, problematic infrastructure, poor assessment tools and admission criteria, and the growing problem of meeting the needs of aging patients. Overall, Dr. Bradford concluded that the infrastructure, staffing, and operational models in place at RTCs at the time did not adequately meet the complex needs RTC patients.

Given these findings, the significant problems raised in last year’s Annual Report, and the thematic focus on mental health for this year, a comprehensive examination of these RTCs on a broader, more systemic level was necessary.

Current Investigation

For the current investigation, I instructed my staff to conduct an in-depth review of CSC’s Regional Treatment Centres. Multiple areas of focus were explored, including but not limited to the governance structure, staff selection and training, the dynamic between security and health care, the quality of mental health care, infrastructure, challenges of the ‘hybrid’ model, deaths in custody and related NBOIs, and examples of promising practices. We employed a range of investigative methods and relied on multiple sources including:

- on-site inspections of each of the five RTCs, including my own visits;

- visits to other forensic hospitals and provincial treatment facilities;9

-

interviews with 150 current and former CSC staff, external stakeholders, and patients;

- CSC staff interviews consisted primarily of RTC senior and middle managers, mental health and health services professionals, and frontline health and operational staff. For co-located penitentiaries, senior managers were also interviewed; and,

- reviews of literature, data, and CSC policy instruments relating to RTCs and mental health.

A total of 12 OCI staff supported the efforts of the current investigation, which was further strengthened by participation from an external subject matter expert and former CSC psychologist and National Investigator. Further to these efforts, the following findings were identified:

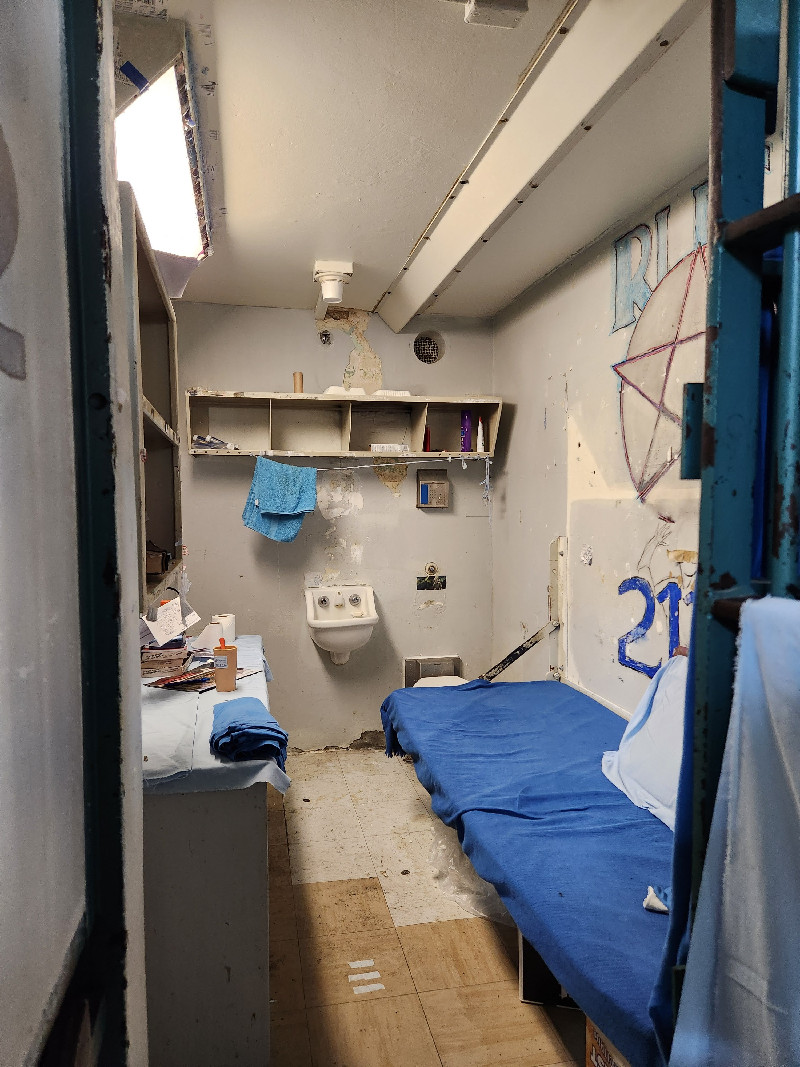

- Outdated and inappropriate infrastructure for a psychiatric and therapeutic hospital setting.

- RTCs have become holding centres for the growing number of aging and infirm persons behind bars.

- Security responses take precedence over the delivery of physical and mental health care.

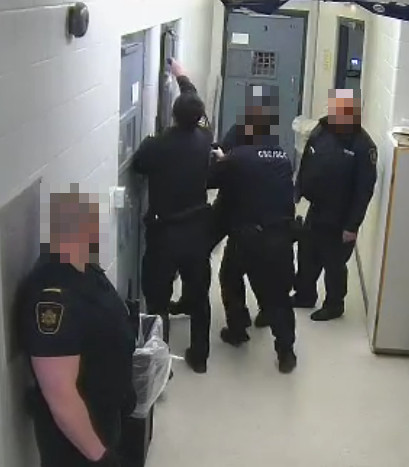

- Over-reliance on the use of force on patients, including the concerning use of OC (oleoresin capsicum) spray as a means to interrupt self-injury.

- Weak governance structure and absence of national policy lead to role confusion and the undermining of clinical decision-making by mental health professionals.

- A lack of specialization required in the recruitment, selection, and training of staff.

- The “stabilization” of behavioural symptoms of mental health appears to be the overriding objective of co-located RTCs.

- Per a review of NBOIs, CSC has systematically failed to learn from or prevent numerous serious incidents and deaths.

- The marked absence of dedicated patient advocates in RTCs infringes on patients’ rights and needs.

Our findings revealed that the long-standing issues and concerns previously raised by this Office and Dr. Bradford are still present today. Additionally, in the context of an aging and increasingly complex population, conditions have arguably worsened since the last reporting on RTCs occurred. These facilities are not positioned to provide specialized, psychiatric hospital care, particularly to those with severe levels of mental and physical needs. At best, they are offering what would be expected of intermediate levels of care for the purposes of stabilization, not longer-term treatment or care. Despite being referred to as Regional Treatment Centres, these facilities essentially amount to penitentiaries offering psychiatric services with limited capacity for emergency care. None of the RTCs live up to their name, nor can they be considered to be classified as a proper psychiatric hospital.

Findings

1. Outdated and Inappropriate Infrastructure for a Psychiatric Hospital and Therapeutic Hospital Setting

The majority of the individuals interviewed for this investigation were asked a fundamental question: Is this facility a prison or a hospital? From an environmental standpoint, that answer is all too obvious. By and large, these centres look and feel no different from any other federal institution. As one Warden put it, “When you walk around the institution, I’ll let you be the judge.”

Furthermore, the age and design of the infrastructure was raised by a large proportion of staff when asked about the biggest challenges they face in providing services in a correctional treatment centre. The Shepody Healing Centre, for example, is found within the walls of Dorchester Institution, constructed in 1880 as a maximum-security institution and currently the second-oldest Canadian penitentiary in operation. Consequently, psychiatric patients are confined to units lined with cramped, barred cells, offering limited treatment and program space. Health care staff charting and discussing patients’ cases must do so in congested control modules, mere feet away from correctional officers. Privacy concerns aside, this proximity is symbolic of an ever-present influence of security staff on the health and mental health disciplines at each of the treatment centres.

The RMHC for instance, forms part of Archambault Institution, originally constructed as a maximum-security institution. RTC (Ontario), comprises two separate 96-bed units, one on the grounds of Bath Institution (medium security) and the other housed at Millhaven Institution (maximum security). As the Office has previously reported, the design of these units can be found in numerous institutions as it lends itself to the convenience of rapid tendering and construction. Elsewhere, this “copy-paste” model has been repurposed to include Structured Intervention Units, Therapeutic Ranges, integrated/non-integrated maximum-security ranges, and transition ranges. As in each of these other applications, RTCs using this design lack sufficient space to provide clinical interventions, programs, education, and Indigenous services. As one Warden described it, “When you plop patients in a 96-man unit and call it a treatment centre, that’s not right. It is not conducive to a therapeutic environment at all.”

Even the only standalone, purpose-built RTC, the Regional Psychiatric Centre, in Saskatoon, which occupies leased property from the University of Saskatchewan, is not immune to the traditional fixtures of a high-security institution. Barbed wire now lines the inner courtyard of the institution, in response to an attempted escape in 2019, despite resistance from the University due to the negative impact this would have on the reprieve the courtyard previously afforded patients. A psychiatrist we interviewed provided significative reflections: “This place was supposed to be a unique facility. It was established to provide high-quality care and be a leader in forensic mental health, clinical teaching, and rehabilitation. It was not designed to be one of the RTCs. We’re not supposed to run just like a penitentiary. This is a prison, with the opportunity for treatment.”

Some modifications have been made to existing infrastructure as attempts to accommodate certain segments of the patient population, such as elderly individuals and those with mobility issues. At the RTC Pacific, for example, the geriatric unit has been retrofitted with larger doors and hospital beds. Despite these changes, all five facilities are structurally and environmentally unsuitable for proper therapeutic or accessibility- minded care.

The Health Centre of Excellence

In the course of this investigation, inquiries were made to identify whether any plans were underway to address these long-standing and well-known infrastructure problems. In response to an information request, CSC relayed that its Technical Services and Facilities Branch is currently in the process of developing new standards for RTCs and therefore halting any new construction, major capital projects, or redevelopment of master plans for all but one facility. The exception is the Shepody Healing Centre, which has long been slated to be replaced by a planned new Health Centre of Excellence (HCoE).

Our Office attempted to obtain more information about the planned HCoE, which was first announced in 2018 as a “national resource” to meet the increasingly complex needs of the patient population.10 Since then, expected costs for the project have ballooned from $300-400 million to approximately $1.3 billion, representing the largest federal investment in New Brunswick since the construction of the Confederation Bridge in the mid-1990s. While CSC has been reluctant to divulge plans for this facility to our Office, information has periodically been shared with the general public over the several years since the project was first announced. For example, on December 19, 2024, the Minister of Public Safety at the time, Dominic Leblanc, confirmed during a press conference that the HCoE will include 150 beds, nearly triple the existing capacity of the Shepody Healing Centre. It will offer bilingual services and accommodate both men and women, including aging patients and those with physical disabilities. Apart from these details, little has been revealed regarding the guiding philosophy, approach to the provision of care, recruitment of suitable staff, etc. that would make this a “Centre of Excellence” that distinguishes itself from the existing RTCs and model.

The project, which has seen multiple delays since its announcement, at the time of this writing, is at the Request for Proposal stage to identify a suitable contractor. While there is a consensus that the Shepody Healing Centre is in dire need of a replacement, the cost of the HCoE is staggering and, as this Office has recommended in the past, CSC should not be in the business of building new, expensive, state-of-the-art options to house individuals requiring significant mental and physical health care. Corrections and specialized mental health care should never be under the same umbrella. This approach is inconsistent with the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules). 11

This Office has seen no evidence to suggest that the HCoE will fundamentally operate any differently than the current RTC model, despite our requests to see such plans. Seven years after its announcement, an empty field next to the existing penitentiary sits idle, awaiting an eventual groundbreaking. The concerning reality is that until the HCoE is operating, patients will continue to be housed in a facility that is grossly inappropriate and inconsistent with a treatment centre, which CSC itself has acknowledged. According to documents provided by CSC, the design and construction phase is expected to extend to 2032. Other than the HCoE, any new construction or major capital projects related to RTCs will be deferred until the new standards are in place, at which point, master plans for the remaining facilities containing RTCs or equivalents will be revisited.

2. RTCs have Become Holding Centres for the Growing Number of Aging and Infirm Persons Behind Bars

“The aging population is another issue. I get lots of referrals for individuals who don’t belong in a hospital bed, are simply aging, and require intravenous medication.”

Chief of Health Care

According to CSC, while 82% of those serving time at a treatment centre have had a mental health diagnosis, 30% of individuals at RTCs do not actually meet CSC’s own criteria for admission (i.e., do not have a Mental Health Needs Scale on file indicating considerable or high needs). These individuals have been admitted to an RTC largely on the basis of “exceptional admission” – individuals with serious physical disabilities who require 24-hour nursing or other clinical care not available in the region. Most common among these are age-related ailments, including hypertension, hepatitis C, tuberculosis, diabetes, dyslipidemia, osteoarthritis, Chronic Kidney Disease, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

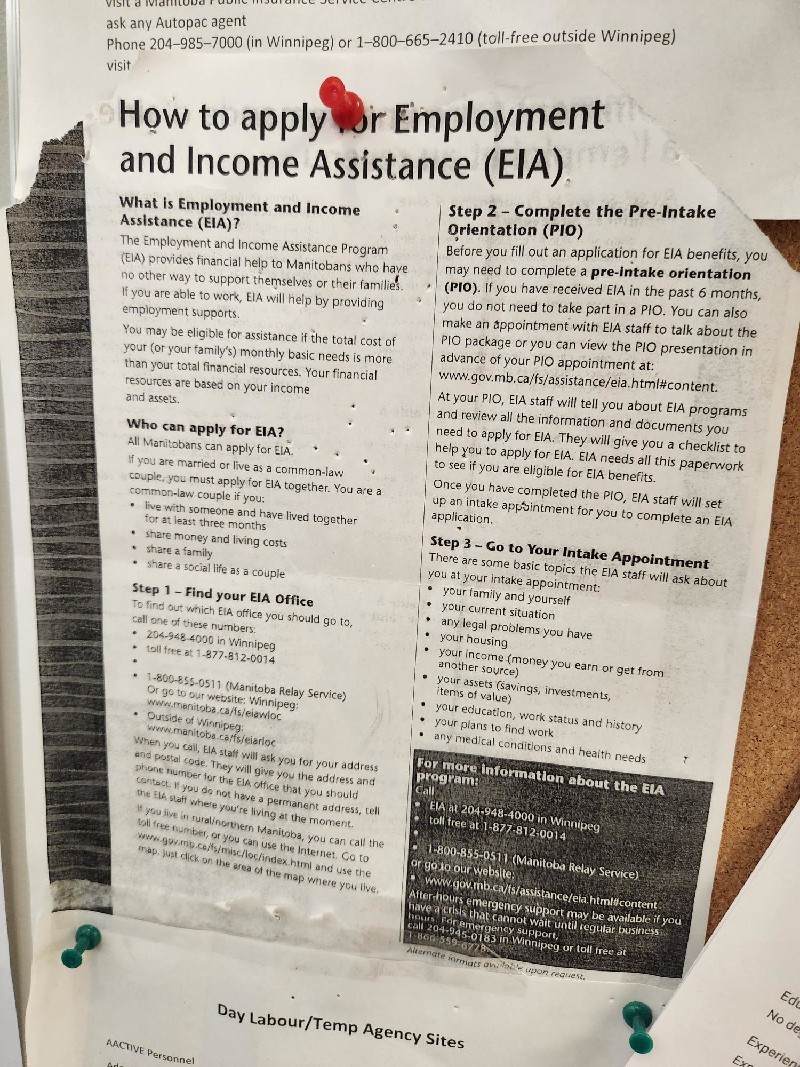

As it stands, the RTCs house a significantly older and infirm population compared to other federal institutions. Specifically, the proportion of individuals over 50 years of age accounts for 42% of the RTC population overall, compared to 26% of their co-located facilities. Individuals aged 65+ represent 25% of individuals in RTC beds, while only accounting for 7% of those in the mainstream facilities. This Office has previously reported on the growing number of aging individuals in federal custody, putting forward recommendations to both the Service and Government to increase release options for the aging and dying, to enhance partnerships with specialized community service providers, and to significantly reallocate existing institutional resources to community corrections to better support the reintegration needs of aging offenders. When walking through these units, it is blatantly evident that these patients would not pose any undue risk to society and could be easily and safely managed in the community, in keeping with CSC’s legal obligation to apply the “least restrictive measures” when administering sentences.

The number of individuals over the age of 50 in federal corrections has continued to increase year-over-year and will continue to do so. Given this trend, the infrastructure and services in place are grossly inadequate to humanely meet the needs of this population. For example, RPC’s psychogeriatric Mackenzie Unit has physical infrastructure challenges, including cells built in the 1970s, without anticipating the room required or unique needs of a geriatric population. Older patients suffering from conditions such as incontinence and needing a brief change, for example, find themselves restricted by institutional routines, including security patrols, designated cell time, or formal counts. These conditions are detrimental to patients’ health and wellbeing as well as to their right to dignified care.

With the growing needs for both physical and mental health care, and the co-occurring nature of these issues that come with age, CSC needs to contend with and resolve the growing demand for specialized care. Quality of care aside, at present, choices are being made and exceptions are being granted for those with pressing physical care needs, which in turn means that many who require psychiatric care remain in a mainstream facility due to a lack of bed space at the RTCs. According to CSC, 3% of the in-custody population meets the criteria for admission to an RTC but are not in an RTC bed. These individuals are mostly in maximum security, are Indigenous individuals, and/or are women. It is our understanding the CSC Health Services sector is currently undergoing an initiative to not only standardize services across RTCs, but to also develop a plan to address these ever-mounting pressures. This Office awaits the outcomes of this much-needed exercise.

3. Security Responses Take Precedence Over the Delivery of Physical and Mental Health Care

“To understand the philosophy of care that has evolved in the treatment centre, one only needs to look at the complement of staff. At the inception of the treatment centre, the staff complement of COs [correctional officers] to nurses was approximately 50 COs to 100 nurses, and nurses were responsible for both physical care and mental health intervention programs, they knew their patients well. At present, there are approximately 130 COs to 48 nurses. Because of the direction that CSC has chosen to take, the treatment centre feels more like a prison today than it ever did.”

Psychiatrist

Unjustifiable Emphasis on Security Measures and Perceptions of Risk

Despite the inclination to impose high security measures and often treat these facilities as maximum-security due to their collocation or presence of maximum-security patients, in reality, they see less gang involvement and violence. Security Intelligence Officers play a different role, as issues such as the introduction of contraband and the presence of Security Threat Groups (STGs) are far less pronounced. One Warden explained that gang membership becomes less of a determining factor at RTCs once individuals realize that they do not have to adopt the same identity as they might in a mainstream institution. He remarked further that “STG guys realize that they don’t need to live up to the label that we, the organization, gave them.”

Over the past five fiscal years, RTCs saw 961 incidents of possession of contraband,12 which represents less than 2% of all incidents of possession of contraband during that time. In fact, staff reported that the diversion of medication, including Opiate Agonist Therapy such as Suboxone, poses far more of a problem in these facilities than traditional contraband found in other mainstream institutions. The diversion of medication by patients involves misdirecting or misusing prescribed medication for personal use or reselling. For example, a Warden noted that “We don’t have an issue with drones here. I’m a big pharmacy. Patients can get whatever they want by talking to a doctor.”

Nevertheless, there is no question that working with a complex, occasionally volatile population carries an inherent risk. Over the last five fiscal years, RTCs saw 34 attempted suicides and nearly 1,500 incidences of self-inflicted injury. During the same period, three patients died by suicide.13

Physical Barriers to Staff-Patient Interaction and Dynamic Security

Violent incidents, including assaults on staff, do occur and can often precipitate the imposition of additional security measures, impacting both physical structure and routine. There is a predominant narrative that correctional staff are “responders,” which, in principle, is counter to the notion of early identification, intervention, and dynamic security, all of which are crucial in a mental health facility. It is unsurprising then, that health care staff at sites where this sentiment is most discernible tend to mirror their correctional counterparts. As an Executive Director frustratingly remarked, “A lot of our nurses wear epaulettes now.”

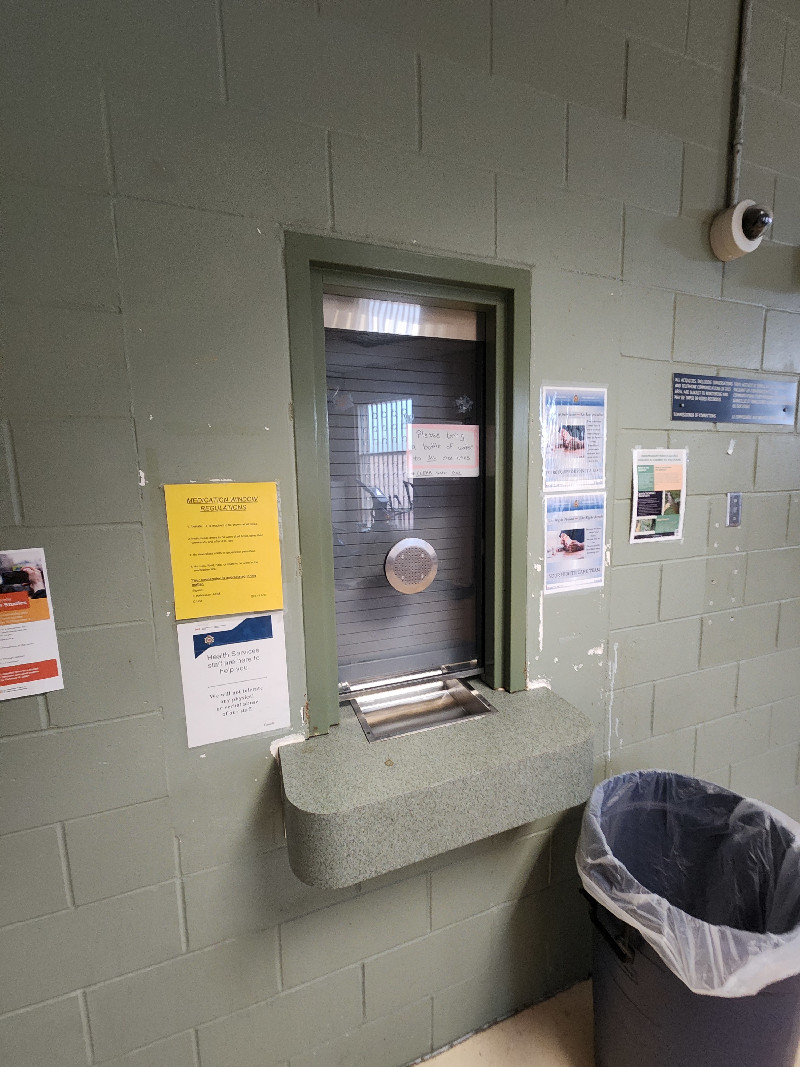

While the instinct to fortify a correctional facility can be understood, some disproportionate safety measures, often in the form of physical barriers, come at great expense to staff-patient interaction, observation, therapeutic rapport, and dynamic service delivery. When face-to-face interactions between patients and staff, whether scheduled or spontaneous, are limited by structures, access to and quality of care are significantly curtailed.

Nowhere was this general attitude and regression more obvious than at the RPC in Saskatoon, where both correctional and health care personnel have increasingly withdrawn from the units, completing more of their duties in control modules and enclosed nursing stations. At the centre of RPC’s Bow Unit, for example, a horseshoe- shaped workstation, originally designed to promote direct observation and interaction with patients, sits abandoned in favour of an inner module and a newly constructed floor-to-ceiling glass partition that puts distance between staff and patients. During our inspection of this unit, negotiation was ongoing with the union representing nursing staff after they were encouraged by management to leave their enclosed nursing station for 15 minutes a day to be more visible to patients, resulting in resistance and demands for more physical barriers.

Compounding security issues, the RTCs are considered to have a multi-level security designation. Commissioner’s Directive 706 - Classification of institutions defines some of these parameters and behavioural expectations as follows:

Security

- The perimeter of the Regional Treatment Centre will be well defined, secure and controlled. Firearms will be retained in the treatment centre and will be utilized for perimeter security. However, they will only be deployed inside the treatment centre during emergency situations with the authorization of the Institutional Head.

Behavioural Norms

- The behavioural norms for inmates at Regional Treatment Centres will reflect their security level, and inmates are expected to comply with their treatment plan and Correctional Plan.

In practice, this means that patients with an Offender Security Level consistent with minimum, medium, or maximum security can be admitted to an RTC from institutions with any of the aforementioned security levels. Once admitted to the RTC, patients may find themselves on living units with individuals previously found to have presented a higher security risk. While managing the complexity of such a population can be a point of pride for some, this typically contributes to the security-focused culture that permeates the RTCs, as correctional staff appeared to focus on the presence of, traditionally classified, maximum-security individuals and therefore default to treating the institution as if it were maximum security. Coupled with the structural trappings of a prison environment, this general attitude makes these facilities feel even further removed from what one would expect from a psychiatric hospital. A psychiatrist characterized the dynamic found at RTCs by stating that “Operational concerns always outweigh clinical concerns.”

While less commonplace than in mainstream institutions, decisions to impose lockdowns are also purely operational, and include little to no clinical consultation on the potential impacts that they can have on the patient population and quality of care. At one site for example, psychiatrists shared that patients were locked in their cells for most of the workday, leaving approximately two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon for patients to be seen by psychiatry, mental health staff, nurses, parole officers, and/or to participate in programming. Furthermore, the presence of security staff on a unit was viewed as so essential to the operational routine, and that if not appropriately staffed with correctional officers, an entire unit would be locked down. That is, patients were locked in their cells, regardless of how many health services staff were on the unit, prepared to see patients.

Cultural and Attitudinal Barriers to Staff-Patient Interaction and Dynamic Security

“The problem is how the language has changed. Even nurses now say inmate instead of patient. If you don’t fit the culture, it spits you out.”

Psychiatrist

"We are sometimes told by the officers, ‘Hey you’re in a pen here’ [...]. Before, if you said ‘I want to see Mr. So-and-so’, you were told that he was not a ‘Mr.’ [...] of course, here you have to find your place without confronting them and I know very well that I can’t give orders to officers."

Nurse

The pervasive reminders that one is in a prison are not only visual, but also extend to the language used by institutional staff in reference to those residing there for treatment. Throughout the course of the investigation, these individuals were continually referred to as “inmates” rather than “patients” by all correctional staff we interviewed. While less frequent, mental health professionals, including psychologists and psychiatrists, occasionally made this distinction, before correcting themselves.

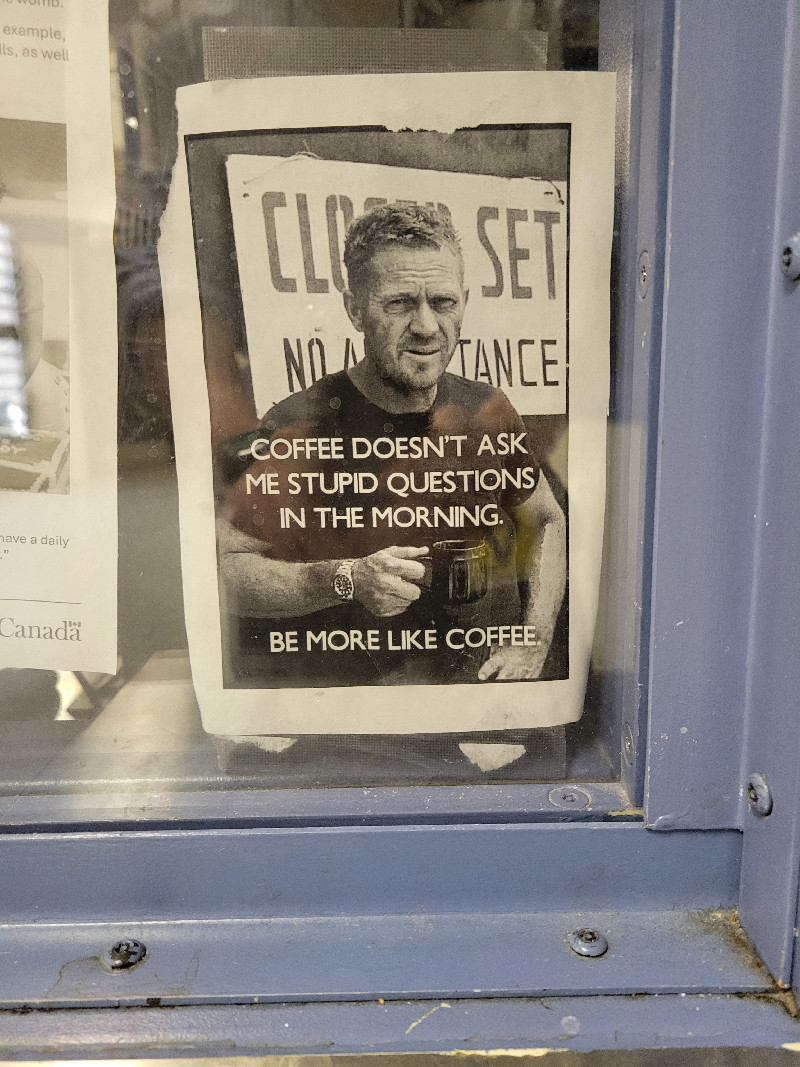

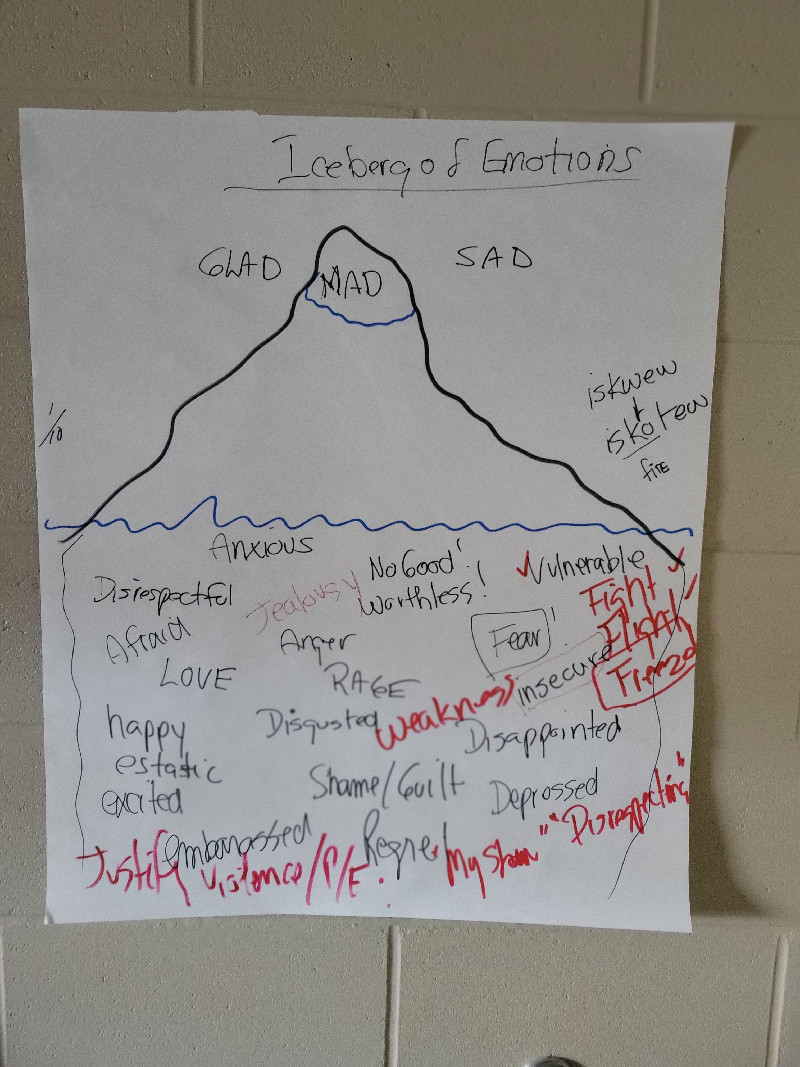

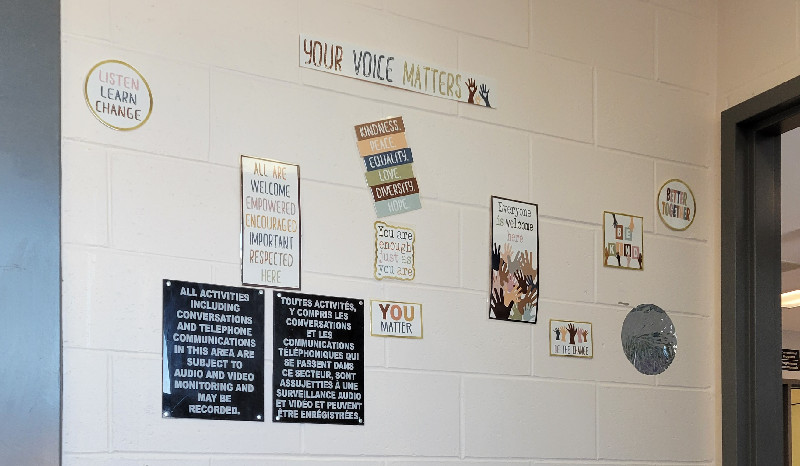

The influence of culture, attitudes, language choice, and perceptions of “inmates” versus “patients” can impose considerable barriers to treatment. This dynamic was evident at all RTCs. The encapsulation of such attitudes was evidenced by a strategically placed poster found near a medication window within the RPC’s Bow Unit control module. The poster was taped on the inside of the structure’s plexiglass with the picture and print facing the patients, the message to patients read as follows:

The othering, belittling, and/or dehumanizing of patients with complex mental health needs in an “accredited psychiatric hospital” is simply unacceptable. This stands in stark comparison to the manner in which security concerns are managed and addressed, and patients are viewed, in provincial forensic psychiatric treatment centres and hospitals whose patient profiles also consists of those with complex mental health needs who, at times, exhibit volatile behaviours. The provincial forensic psychiatric centres we visited informed us that the first point of contact for all patients are health services and mental health professionals. In fact, their security partners are not present on units, do not manage movement, and do not conduct rounds, all of which are commonplace in a federal treatment centre. Rather, at the first indication that a patient appears to be struggling or showing signs of distress, health services and mental health staff engage the patient, in an effort to avert, manage, and/or stabilize the individual.

The ability to foresee and observe signs of distress or decompensation requires significant familiarity, observation, and interaction with patients - a full-time, round-the-clock job. Only as a very last resort, when a patient is aggressive, should security partners be called for assistance. Their role at the time of their arrival is clearly conciliatory and de-escalation with physical handling should be used only if required to ensure patient and staff safety. Of course, the ability to foresee and observe signs of distress/decompensation and to avert aggressive behaviour is not always possible. Provincial forensic psychiatric hospitals have had their share of incidents when health services staff were harmed, or a patient has escaped. Despite this, they have remained loyal to their mission and mandate of being a psychiatric hospital and held back from quickly using static, security-focused solutions. These facilities stand as proof-of-concept that correctional treatment centres can be run in a health-first manner, when there is the organizational will, commitment, and support of such a fundamental philosophy and operational approach.

For example, following an escape at one of these provincial forensic facilities, and despite pressure to install razor wire, the potential for a patient to be ensnared, entangled, and mangled in razor wire factored heavily in their deliberation of options. Alternatives were therefore explored and resulted in a “candy-cane” fence being installed – a fence that has an aluminum casing at its top, in the shape of a candy cane – that makes future escapes difficult, but results in less risk to patient safety. Similarly, following incidents of staff being physically harmed, the hospitals increased training and developed more effective de-escalation skills, initiated meaningful (internal and external) reviews of the incidents which they used as an organizational learning tool. Recommendations from such reviews, particularly those that benefited the welfare and safety of the patients and the public, were welcomed – rather than dismissed.

While some RTC staff noted that a perceptible decline in dynamic security has been steady and long-standing, some staff were of the opinion that the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic also saw a significant shift in this dynamic. Staff suddenly perceived patients as an additional risk to them and their families. As a result, the quality and quantity of interactions diminished. This reversal in dynamic security and patient engagement mirrors the trend that the Office found in its investigation of men’s standalone maximum-security institutions in 2023-24 14

A Clash Between Operational and Health Care Sectors

“Governance is a huge issue. The current model is awful. Health policy is very clear; Operations policy is very clear; but Regional Treatment Centre policy is non-existent. It does not allow us to work in the grey.”

Warden

“I strongly believe that we need our own policy. We try to be health and operations and the two do not work together. We’re driving down different roads but are we going to the same place?”

Deputy Warden

“There’s always a bit of disagreement here. There is a gap between health and operations and the balance between the two remains fragile. This has an impact on the working climate.”

Correctional Manager

Increases in the securitization of treatment centres (infrastructure, protocols, and staff culture), coupled with decreases in dynamic approaches to security and treatment, are further hampered by clashes between health care and operational sectors. In the course of this investigation, perhaps one of the best illustrations of this rift emerged following the release of a case report from the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner (PSIC) in March 2020, which found that “CSC neglected to take adequate action to stop acts of insubordination, and harassment and intimidation by several Correctional Officers against other employees within the Regional Mental Health Centre (RMHC), at the Archambault Institution.”15 The report detailed systemic harassment by RMHC correctional officers directed toward mental health professionals working on the units and various managers, due to the desire of the correctional officers dictating where a psychologist was allowed to see a patient.

In protest of management’s support for the psychologist to provide counsel to the patient in their office, a correctional officer assigned to the RMHC left his post. This left several RMHC employees locked in offices with patients with no nearby support for nearly 30 minutes, while a nurse was locked on a range full of patients in a similar predicament. The PSIC report documented the following examples of harassment:

“Some Correctional Officers displayed a children’s teddy bear as a pejorative reference to the work of RMHC employees.

Some Correctional Officers made and displayed banners with discriminatory messages that belittled and mocked the RMHC inmates with mental health issues and the work of RMHC employees.”16

The events, coupled with related and unrelated acts of insubordination, racism, and intimidation by the correctional staff toward colleagues, are a clear example of the fundamental difference in perspective about security versus patient care. During the current investigation, similar accounts emerged. For example, two mental health professionals we interviewed at one treatment centre recounted that approximately two years prior, correctional staff tried to convince patients on a unit that a dog was present, going so far as to bring in a bowl of water and dog food for the sole purpose of confusing patients for their own amusement.