Ten Years since Spirit Matters: A Roadmap for the Reform of Indigenous Corrections in Canada

Cat. No.: PS104-20/2023E-PDF

ISSN: 978-0-660-49732-7

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the significant contributions of many individuals and organizations. Many thanks to the following:

The lead OCI authors, researchers and principal investigators who led this work:

Leticia Gutierrez, PhD

David Hooey

Emad Talisman

Hazel Miron

All individuals who generously shared their experiences, perspectives, and stories with us, including the following:

- Currently and formerly incarcerated Indigenous individuals;

- Elders, Spiritual Caregivers, and Knowledge Keepers;

- Local staff working in the variety of settings we visited e.g., federal institutions, healing lodges, community setting/facilities)

Archipel Research and Consulting, for providing support in interviewing Elders, contributing to the findings of the investigation, and offering review and feedback on Part Two of the investigation.

The organizations and community groups who graciously met with us to discuss these issues from their experiences and respective vantage points, including:

- Métis National Council

- Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami

- Native Women’s Association of Canada

- Native Counselling Services of Alberta

OCI staff who conducted numerous interviews and site visits.

CSC headquarters and regional staff who provided helpful insights and information to support these investigations.

Preface

The disproportionate and growing number of Indigenous individuals behind bars is among Canada’s most pressing human rights issues, and it has featured prominently in all public reports issued by my Office over the past decade. The current publication was initially conceived as a two-part update of the Office’s original 2013 Special Report to Parliament entitled, Spirit Matters: Aboriginal People and the Corrections and Conditional Release Act . Part One of the update of Spirit Matters was published in the Office’s 2021-22 Annual Report and Part Two was subsequently released in the 2022-23 Annual Report. Ten Years Since Spirit Matters: A Roadmap for Reform brings together these two separately published reports into a single source. In consolidating findings and recommendations, A Roadmap for Reform represents the Office’s most current assessment of how the federal correctional system perpetuates disadvantage and fails Indigenous people.

Professionally and personally, this work grows out of increasing frustration with the futility of responding to the crisis of Indigenous over-incarceration in Canada with more of the same failed policies and approaches. As Canada’s Correctional Investigator, I am deeply troubled each time that I report on the state of Indigenous over-representation in Canadian prisons. Despite numerous reports and recommendations on this topic, and despite all the resources and strategies put toward addressing this problem, the percentage of incarcerated Indigenous people grows relentlessly. Today, nearly one-third of the overall incarcerated population identifies as Indigenous; 50% of all women behind bars are Indigenous. Without necessary and urgent reforms, the already unconscionable Indigenization of Canada’s correctional population will persist.

A Roadmap for Reform is the culmination of a decade of observations, reflections, engagements, investigations, interviews, findings and recommendations documenting the experience of Indigenous people serving federal sentences in Canada. Importantly, in this compendium we sought to capture the voices and experiences of federally sentenced Indigenous peoples in their own words. It also features the unique perspective and wisdom of Elders working inside federal penitentiaries providing support and guidance to their ‘relatives.’ These individual narratives and testimonies, powerful and significant in their own right, are supported by a series of investigations into signature initiatives in the Correctional Service of Canada’s Indigenous continuum of care .

The project team took seriously the need to apply an Indigenous lens to this work, to listen, consult and engage collaboratively with Indigenous individuals, organizations, partners and stakeholders, all of whom have a unique vantage point on the issues that affect Indigenous people caught up in Canada’s criminal justice and correctional systems. This work simply would not have been possible without the contributions of an extraordinary and committed team of policy advisors, writers, researchers, investigators and external collaborators. Capturing a wide spectrum of perspective and insight, this book is a distillation of what we heard and witnessed over the course of one of the most ambitious and comprehensive investigations ever conducted by the Office of the Correctional Investigator. I am immensely grateful to all who contributed to making this publication possible.

Written in the spirit of reconciliation, this compendium puts forward the case for bold and innovative reforms to Canada’s approach to Indigenous Corrections. It calls on the Government of Canada to loosen the levers and instruments of colonial control that keep Indigenous people marginalized, over-criminalized, and over-incarcerated. It makes the case for reallocating current spending and resources in federal corrections to match the proportion of Indigenous people under federal custody. Consistent with principles of self-determination, federal powers and authorities extending to the care, custody and supervision of Indigenous offenders should be totally devolved and transferred to Indigenous communities and organizations, inclusive of turning over the six remaining state-run Healing Lodges to First Nation, Métis or Inuit control, as originally intended. Finally, the Roadmap calls for the creation of an Indigenous decarceration strategy co-developed in partnership with the federal government and Indigenous people and organizations. Such a strategy would include measures to address why Indigenous people are more likely than any other group to be over-classified, more likely to be involved in use of force incidents, less likely to be granted discretionary release and more likely to spend longer incarcerated before first release.

It is my view that the findings and corresponding recommendations offered in this book constitute essential directions for the transformational reform of Indigenous Corrections in Canada.

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

July 2023

Part 1

The mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples has been a long-standing blight on Canadian history, and by extension, Canadian corrections. A system that has been referred to by some as the new residential school system, corrections has become emblematic of modern neocolonialism and a microcosm for broader social ills. 1 It is true that the prison system is often blamed for, and inherits, the failures of other social institutions. While not solely responsible for who enters its doors, correctional agencies hold considerable power over how (and to whom) justice is administered behind bars, which to a large extent, dictates the composition of the correctional landscape. Moreover, correctional authorities have always had significant control over the prevailing cultural ethos of how prisons are run, who runs them, and where resources and priorities are allocated and determined. All of these realities have served to preserve the prison system as the inherently colonial institution that it has always been, despite some attempts to improve it. At an instrumental level, the federal prison system, which predates Confederation, has long served to keep Indigenous Peoples marginalized, over-criminalized, and over-incarcerated.

The inequities and disparate outcomes experienced by Indigenous Peoples under federal sentence in Canada has been a key priority and concern for this Office since its inception. Nearly 50 years ago, in the very first annual report issued by the Office in July of 1974, the discriminatory treatment of Indigenous persons in federal custody was among the inaugural set of issues raised. In the decades to follow, this Office has issued more than 70 recommendations specific to Indigenous corrections, by way of our annual reports. In 2013, the Office’s Special Report on Indigenous corrections entitled, “Spirit Matters: Aboriginal People and the Corrections and Conditional Release Act ,” was tabled in Parliament. 2 Twenty years out from the introduction of the CCRA in 1992, Spirit Matters sought to investigate the extent to which federal corrections had fulfilled parliament’s intent with respect to legislative provisions, with a specific focus on sections 81 (Healing Lodges managed by Indigenous communities) and 84 (Indigenous community release and reintegration planning) of the CCRA. 3 The findings from this investigation revealed numerous and significant gaps. Together, recommendations stemming from Spirit Matters and OCI annual reports on Indigenous corrections have covered numerous topics, focusing largely on the need for change in the following key areas:

- Expansion of section81 Healing Lodges (managed by Indigenous communities);

- Increasing the use, and facilitating the process, of section84 releases;

- Increasing Indigenous leadership (i.e., the appointment of a Deputy Commissioner of Indigenous Corrections);

- Improving the timely release and reintegration of Indigenous Peoples;

- More intentional and transparent analysis and public reporting on the impacts of correctional decision-making on Indigenous populations;

- Increasing the allocation of resources and involvement of Indigenous communities and organizations in correctional decision-making and administration;

- Improving custodial and community-based programming to address the needs of Indigenous Peoples;

- Increasing the use of Gladue /Indigenous Social History factors to inform decision-making, assessment, and classification;

- Resolving the recurring issues faced by Indigenous Elders;

- Increasing the number of Indigenous employees and providing greater training for existing staff on Indigenous culture, history, and spirituality; and,

- Developing a gang disaffiliation strategy, with a focus on Indigenous gangs.

In the years since Spirit Matters , there have been a number of commissions, inquiries, unprecedented pieces of investigative journalism, and parliamentary committee studies conducted on the needs and experiences of incarcerated Indigenous individuals. The reports stemming from most of these initiatives have issued specific recommendations and calls-to-action, many of which have been directed at federal corrections. Concerns raised in each of these reports by-and-large echo many of those made by this Office, and some (e.g., MMIWG Final Report: Reclaiming Power and Place ) have fully endorsed and reissued Office recommendations on Indigenous corrections, often verbatim. Specifically, considerable overlap in recommendations exist in the calls-for-change in the following four areas:

- Increasing the use of Healing Lodges, section84 releases, and engagement with Indigenous communities;

- More and higher-quality culturally-informed programming;

- Improvements to screening, assessment, and classification tools; and,

- More Indigenous leadership, employee representation, and cultural competence among all staff.

Key Reports on Indigenous issues in the Correctional System since Spirit Matters (2013)

- Office of the Correctional Investigator – Spirit Matters: Aboriginal People and the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (2013)

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission – Final Report: Honouring theTruth, Reconciling for the Future (2015)

- Office of the Auditor General – Fall Report: PreparingIndigenousOffendersforRelease (2016)

- House of Commons Standing Committees on Public Safety and National Security (SECU) – Study: Indigenous inmates in the federal correctional system (2017)

- House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women (FEWO) – Study: Indigenous Women in the Federal Justice and Correctional Systems (2017)

- National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (NIMMIWG) – Final Report: Reclaiming Power and Place (2020)

Ten Years since Spirit Matters

Indigenous Over-representation in Federal Corrections

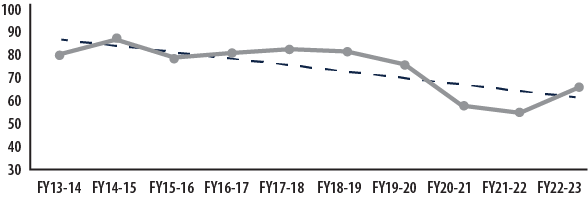

Over the last thirty years in particular, some efforts have been made to bring greater equity to Indigenous Peoples who enter the correctional system, such as the introduction of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (sections79 to 84) and changes to the Criminal Code (e.g., s.718.2 [ e ]). In federal corrections, systemic efforts to “decolonize” prisons largely started in 2003 with the introduction of the Aboriginal Continuum of Care model. Despite the various changes, inquiries, plans, and investments, by many metrics, the various efforts have fallen disappointingly short of their goals of addressing systemic discrimination and the over-representation of Indigenous Peoples in the correctional system. While we have seen overall declines in the incarcerated population in recent years, Indigenous over-representation has not only persisted but increased at an unabated pace. Since 2012, the federally incarcerated population decreased by 16.5% and the in-custody population of White individuals decreased by 23.5%; however, during the same time, the Indigenous custodial population increased by 22.5%. 4 Over the last decade alone, the total Indigenous offender population (incarcerated and community) has increased by 40.8%. 5

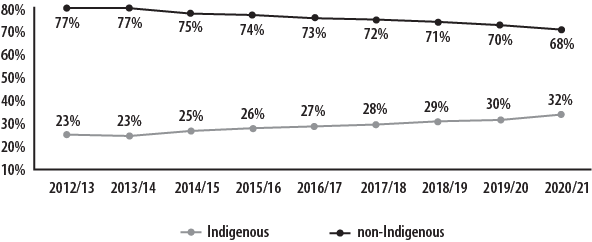

In January 2016, my Office reported that the proportion of Indigenous Peoples in federal custody had reached an all-time high of 25%, and cautioned that this trend would continue, without significant intervention. Over the last two years, federal corrections reached two new historic milestones when the proportion passed the 30% mark overall, and approached 50% for incarcerated Indigenous women. 6 Today, despite accounting for approximately 5% of the adult population, Indigenous Peoples continue to be vastly overrepresented in the federal correctional system, accounting for 28% of all federally sentenced individuals and nearly one third (32%) of all individuals in custody.

Graph1. Proportion of Indigenous and non-Indigenous in-custody Population since 2012 7

Prison Health and Outcomes

While the worsening over-representation and deepening Indigenization of the correctional system alone serves as a grim litmus test for progress, a wide range of prison health indicators and outcomes similarly provide further evidence of the troubling trajectory of Indigenous corrections. For example, as of the writing of this report, Indigenous Peoples in federal prison continued to be overrepresented in the following areas:

- Custodial settings, compared to community supervision (68.3% of Indigenous Peoples are in custody versus 54.8% of non-Indigenous individuals);

- Uses of force (Indigenous individuals accounted for 39% of those involved in a use-of-force incidents over the last five years);

- Maximum security (38% of individuals in maximum security are Indigenous);

- Structured Interventions Units (formerly segregation, nearly 50% of individuals in SIUs are Indigenous);

- Security Threat Group affiliations (the proportion of Indigenous individuals with an STG affiliation is twice that of non-Indigenous individuals in custody i.e., 22% vs. 9%) 8 ;

- Self-injury incidents (55% of all incidents of self-injury involved an Indigenous person);

- Attempted suicide incidents (40% of attempted suicides over last decade); and,

- Suicides (83% [5 out of 6] of all incarcerated individuals whose death occurred by suicide in 2020/21 were Indigenous). 9

Furthermore, Indigenous individuals are increasingly entering the system at a younger age 10 , spending considerably longer behind bars, and returning to federal corrections at unprecedented rates compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. Specifically, Indigenous Peoples continue to serve higher proportions of their sentences compared to non-Indigenous individuals before being released on day or full parole and receive a very low proportion of conditional releases, with statutory release being by far the most likely release type. 11 In 2020/21, 75% of releases for Indigenous offenders were statutory releases. 12 As for post-release outcomes, Indigenous men have the highest rates of recidivism than any other group (65% for any re-offence, with rates of 70%+ in the Prairie region) and nearly half of all Indigenous admissions to federal corrections last year were for revocations. 13 , 14 Individually, and taken together, these indicators clearly show that Canadian corrections is, and has been for some time, at a point of perpetual crisis. Year over year, prisons are increasingly being filled by Indigenous Peoples who are caught up in the proverbial revolving door, experiencing worse circumstances while inside, with few viable options for getting out and staying out.

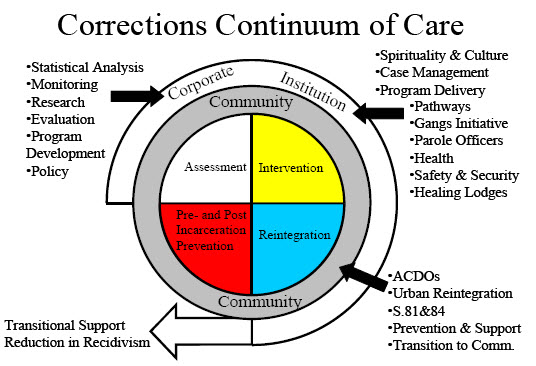

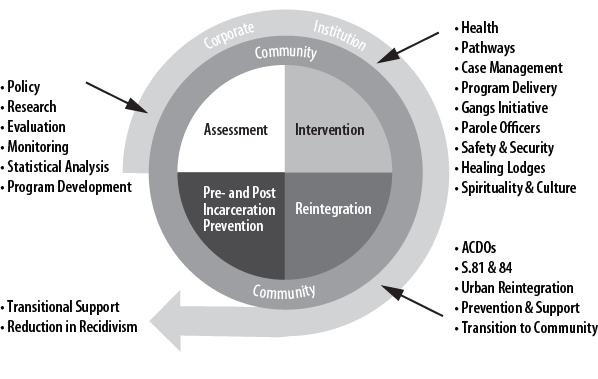

CSC Progress on Recommendations

While largely unresponsive to recommendations put forward by this Office and others, in the years since Spirit Matters , CSC has developed no shortage of plans and initiatives for Indigenous corrections. Mainly by way of the Aboriginal Continuity of Care Model (2003), Strategic Plan for Aboriginal Corrections in 2006 (followed by its “renewal” in 2013), and later the National Indigenous Plan – A National Framework to Transform Indigenous Corrections (2017), CSC has repeatedly made commitments to “transform” Indigenous corrections by enhancing initiatives along what it refers to as the Indigenous Continuum of Care, such as:

- Expanding Healing Lodges, section84, and Pathways capacity; 15

- Increasing the numbers of Indigenous staff and cultural competence of staff;

- Creating greater collaboration with Indigenous communities;

- Enhancing culturally-appropriate interventions and programs;

- Addressing the mental health needs of Indigenous offenders; and,

- Improving reintegration results in an effort to close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous offenders. 16

Despite continuously evolving and ever-expanding corporate plans and intentions for Indigenous Corrections, today’s iteration of the Indigenous continuum of care model continues to be replete with unfulfilled commitments, for example:

- disparities in the validity of risk assessment remain unresolved, despite the Supreme Court of Canada ruling in Ewert v. Canada; 17

- coordinated efforts to address the mental health needs of Indigenous individuals (in particular, Indigenous women) are non-existent;

- the use of Indigenous Social History in decision-making continues to be as inconsistent and perfunctory as it was at the writing of Spirit Matters ; and,

- Indigenous correctional programming is arguably less effective now than it was a decade ago.

Over the last few years, greater awareness brought about by large-scale commissions and inquiries, mounting social pressure, and a considerable (and more transparent) shift in government mandates and priorities toward reconciliation, the government has made substantial financial investments in the federal Indigenous corrections portfolio. Through Budget2017, for example, CSC received $55.2million dollars (and $10.9million ongoing thereafter) to enhance its capacity to provide effective interventions for Indigenous offenders. 18 Even a cursory review of what those plans and investments have yielded are disconcerting, and the little progress CSC has made on meeting their own commitments further illustrates why this Office, among many others, are frustrated with the Service’s ineffectiveness on Indigenous corrections. Signature investments appear to be put toward CSC-developed custodial initiatives, such as Indigenous Intervention Centers (IIC) that, by all accounts, appear to be little more than early or targeted correctional case management by another name. Similarly, long-standing institutional correctional initiatives, such as Pathways, continue to receive substantial resources, with little in the way of external evaluation or validation of their effectiveness or whether they are serving the needs of Indigenous persons in custody, particularly those who need the most support. Proportionally little new funding has been allocated to Indigenous controlled or run community correctional initiatives. The focus of CSC’s Indigenous correctional efforts continues to be mainly prison-based. I would like to take a moment to highlight a few specific areas of concern where there have been focused recommendations issued and commitments made.

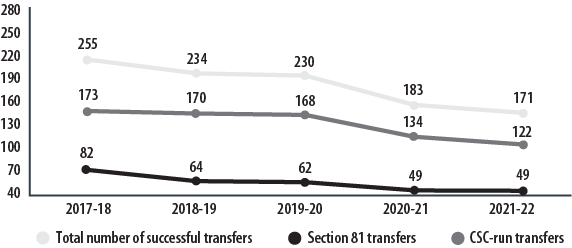

Healing Lodges and Section84 Releases

Of all of the recommendations that have been issued to the Service on Indigenous corrections, the expansion of Healing Lodges (Section81) and section84 (Community Release) are the two made most frequently. Despite identifying these sections of the law as priorities themselves, CSC has made very little progress. Since Spirit Matters , there has been the addition of one new Healing Lodge (i.e., Eagle Women’s Healing Lodge in Manitoba) and the number of spaces in community-run Healing Lodges has increased by only 53 beds – a number vastly insufficient to keep pace with the growing proportions of Indigenous people entering federal custody. Furthermore, there continues to be no Healing Lodge capacity in the Ontario and Atlantic regions, which have both seen substantial increases in Indigenous admissions, particularly the Atlantic region where the incarcerated Indigenous population has increased by nearly 90% in the last ten years.

With an already limited number of Healing Lodge spaces, it should be noted that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a marked impact on Healing Lodge occupancy rates. For example, in the two years prior to the pandemic, the average occupancy rate of Healing Lodges was around 78%. At the writing of this report, the average occupancy rate was approximately 51%, which begs the question – with so few Healing Lodges spaces available, why are occupancy rates so low? I intend to examine this question, among others, in the coming year.

Table 1. Ten-Year Comparison of Capacity and Occupancy Rates

| 2012/13 | 2021/22 | ||||||

| Facility | Rated Capacity | Actual Capacity | % Occupied | Rate Capacity | Actual Capacity | % Occupied | Pre-COVID 2-year Average % Occupied* |

| Community-run s.81 Healing Lodge | |||||||

| Stan DanielsHealing Centre | 30 | 19 | 63.33 | 30 | 13 | 43.33 | 53.33 |

| O-chi-chak-ko-sipiFirst NationHealing Lodge | 24 | 22 | 91.67 | 24 | 12 | 50 | 81.25 |

| WaseskunHealing Centre | 15 | 15 | 100 | 15 | 8 | 53.33 | 80 |

| Buffalo Sage | 12 | 16 | 133.33 | 28 | 21 | 75 | 91.1 |

| Prince AlbertGrand Council Healing Lodge | 5 | nr | – | 12 | 7 | 58.33 | 83.3 |

| Eagle Women’s Healing Lodge** | – | – | – | 30 | 4 | 13.33 | 0 |

| CSC-operated Healing Lodge | |||||||

| KwìkwèxwelhpHealing Village | 50 | 44 | 88 | 50 | 20 | 40 | 81 |

| Pê SâkâstêwCentre | 60 | 47 | 78.33 | 60 | 44 | 73.33 | 79.17 |

| Willow CreeHealing Centre | 40 | 40 | 100 | 80 | 33 | 41.25 | 66.88 |

| Okimaw OhciHealing Lodge | 40 | 33 | 82.5 | 60 | 36 | 60 | 85.58 |

| TOTAL | 276 | 236 | 85.5 | 389 | 198 | 50.9 | 77.97 |

Note: Occupancy data was obtained from CSC’s Corporate Reporting System – Modernized (CRS-M) : Institutional Counts report; nr = not reported.

*2-year average % occupancy is based on the rated vs. actual capacity counts from 2018/19 and 2019/20, to get a sense of pre-pandemic occupancy.

**Eagle Women’s Healing Lodge opened as a s.81 facility in 2019.

In addition to the limited changes in capacity, there does not appear to have been any appreciable changes to the mechanisms for establishing section81 or section84 agreements with Indigenous communities or organizations. These concerns, coupled with the narrow eligibility criteria for admission to most Healing Lodges, seriously call into question whether Healing Lodges are being set up to serve the needs of a significant proportion of incarcerated Indigenous individuals.

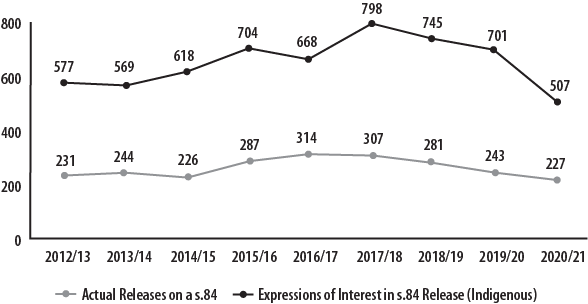

Similarly, with section84, we have seen little in the way of movement on commitments and recommendations since Spirit Matters . 19 The number of individuals expressing an interest in, or receiving a section84 release, has remained essentially unchanged today compared to 2012. While the increases in the number of Indigenous admissions over time alone should have resulted in a corresponding rise in the number of section84s, modifications to the cumbersome and bureaucratic process of section84, as recommended, should also have theoretically resulted in improvements – and thus, increases – in the use of this release process.

Graph2. Expressions of Interest and Actual Releases on Section84 from 2012 to 2021 20

Indigenous Representation and Cultural Competence

Despite various commitments in this area, the lack of Indigenous representation among CSC staff, particularly in leadership positions, as well as the reportedly low levels of cultural awareness is a long-standing problem on which CSC has made seemingly few significant inroads. Nationally, Indigenous individuals continue to be underrepresented among staff relative to the composition of the incarcerated population (i.e., 10% of CSC staff identify as Indigenous versus 32% of incarcerated individuals), and are even more vastly underrepresented in leadership positions. For example, according to data provided by CSC, of the 111 executive level positions at national headquarters, only three (2.7%) are occupied by Indigenous individuals. Similarly, for Elders, who already face numerous vulnerabilities – in large part due to their employment status as contractors – are too few in number to serve the growing population, are spread thin, and are expected to play many different roles. There are currently only 133 Elders across the country for the 3,953 Indigenous individuals in custody. While not all Indigenous individuals will seek to work with an Elder, these numbers translate to an overall ratio of 30 Indigenous persons for every one Elder. Though the ratio of Elders varies considerably by institution and region, the Prairie region has the largest number of incarcerated Indigenous individuals and the worst Elder to prisoner ratio, with an average of 35 to one. One institution has a ratio of 105 Indigenous prisoners to one Elder.

While there are complexities to recruiting and retaining Elders to work in the prison setting, many of the surmountable barriers that have existed for attracting and keeping Elders (among other Indigenous staff) have gone unresolved. Some have attributed this to a lack of understanding or appreciation for the work that Elders and other Indigenous staff do. We have heard time and time again that the work of Elders, among others, is not given the credibility it deserves, nor the credibility that is bestowed upon other sectors or positions in case management and intervention work. Clearly, more needs to be done not only to recruit more Elders and to protect those who are currently undertaking this work, but also to educate staff more broadly on the important role that Elders and Indigenous departments play in advancing rehabilitative and healing work.

Based on information and feedback we have received, the various plans and strategies that CSC has created to address the issue of representativeness and recruitment have seemingly been largely ineffective (e.g., National Aboriginal Employee Consultation: Working Together in Partnership Toward Inclusion, 2012; Connecting Spirits, Creating Opportunities , 2019). Furthermore, staff members and incarcerated persons alike have told us that cultural competency training is inherently limited in its value and impacts, often providing largely surface-level, pan-Indigenous perspectives on Indigenous worldviews and ways of knowing. Greater cultural awareness and credibility would be brought about by improved recruitment, retention, and promotion of Indigenous staff, which in turn would have a direct impact on the lives of federally sentenced individuals. Plain and simple, CSC needs to do more to attract and hire Indigenous Peoples, to recognize and promote the value of their work, and collaborate in earnest with Indigenous communities to meaningfully move the yardstick on these issues. The lack of progress on Healing Lodges, section84, Indigenous representation, and cultural competency serve as undeniable examples of the consequences attributable to the absence of a national community engagement and co-development strategy for Indigenous corrections – a gap that, in my view, has had an unprecedented impact on the Service’s ability to produce transformative change for Indigenous corrections.

A Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections

The need to appoint a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous corrections is a recommendation that this office has issued nearly a dozen times over the last twenty years, and has been repeated by other committees and commissions who similarly recognize the need for dedicated Indigenous leadership and decision-making power in federal corrections (e.g., NIMMIWG, 2020; House of Commons Standing Committee on the Status of Women, 2017; House of Commons Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security, 2017).

In June 2021, in what this Office viewed as a promising step forward on this recommendation, the government identified the following short-term priority and goal in the National Action Plan in response to the final report of the NIMMIWG:

Goal #6 (d): “Create a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections and address issues for Indigenous women and 2SLGBTQQIA+ offenders…”

In October 2021, this Office requested an update from CSC on its plans to fulfill this commitment. In January 2022, CSC provided the following response: “CSC’s position remains the same – there are no plans to create a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections.”

On May 27, 2022, the Minister of Public Safety’s mandate letter to the Commissioner of Corrections called for the creation of a new position of Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections .Days later, in a statement released in response to the findings from the Auditor General’s report on federal corrections, the Commissioner of Corrections noted, “I am in the process of staffing a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections position.”

I am pleased to see this item raised in the mandate letter and am encouraged by the Commissioner’s response. Given the lack of progress over the last two decades on this particular recommendation, however, I will wait to consider this issue closed once a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections is officially in place. In the meantime, I offer the following (and hopefully last) recommendation on this issue:

- I recommend that CSC consult with Indigenous community groups on the job description, role, mandate, and hiring process for the Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections position, and that they report publicly on their plans and short-term timelines to create and staff this position.

Next Steps

In recent years, this country has faced a reckoning for the intergenerational abuses perpetrated by governments, institutions, and individuals, against Indigenous Peoples. From grassroots organizations to various levels of government, there has been a groundswell of recognition and renewed sense of urgency around the need to repair relationships and systems, including corrections, which have long been broken. In June 2021, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) Act came into force, providing a much-needed roadmap for broader reconciliation in Canada. In the mandate letter to the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada, the government committed to the development of an Indigenous Justice Strategy “to address systemic discrimination and the over-representation of Indigenous people in the justice system”. While large-scale justice strategies in this area have tended to focus on the contributions of policing and the courts, in order to develop an effective strategy to address discrimination in the justice system, federal corrections must be part of the conversation. In an effort to leverage the momentum of existing government initiatives in this area, specifically, the development of a national justice strategy, I am issuing the following recommendation:

- I recommend the Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada include the Correctional Service of Canada and the Office of the Correctional Investigator in the development and implementation of the Indigenous Justice Strategy (IJS). Furthermore, the IJS should seek to redistribute a significant portion of the current resources within the federal correctional system to Indigenous communities and groups for the care, custody, and supervision of Indigenous Peoples.

Furthermore, federal corrections needs to be held accountable to concrete and measurable targets and results, particularly those under their direct control, and more effectively use its levers of influence to address long-standing barriers, such as the over-retention of Indigenous Peoples behind bars and the high rates of recidivism. Of course, federal corrections cannot meet the task on their own. Being included in a coordinated, Indigenous-led, national engagement strategy is a necessary step toward resolution. At the most basic level, the correctional system should not serve to further perpetuate disadvantage, which is precisely what we have seen reflected in the outcomes and prison health indicators for incarcerated Indigenous Peoples, particularly when compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts. The promise of administering an Indigenous person’s sentence through a Gladue -informed lens has not materialized, and, in practice, family and community histories of fragmentation, dislocation and dispossession are too commonly used to validate higher security classifications and lower reintegration potential scores. Corrections has an admittedly complex set of issues to contend with, but we have reached a point where complexity is no longer a sufficient excuse for stagnation.

Part 2

“Our over-representation bothers me. We didn’t need prisons pre-contact! We knew when people needed us and supported each other.”

– Elder

“We feel that as First Nations Inmates, the treatment we are receiving … is on a level of colonial residential school treatment. We have been put down, we have been lied to! Our culture and spirituality has been taken away, yet again, by abuse. This is not fostering relationships.”

– Incarcerated Indigenous individual

“Corrections is a strong example of a bigger problem. They make decisions without a cultural understanding and its being done under the guise of being ‘Indigenous-led’.”

– Community-run Healing Lodge staff

“There is a break in CSC’s continuum of care – and there is no real continuity of cultural care.”

– Staff

Introduction and Context

The over-representation of Indigenous peoples in federal penitentiaries has been an area of documented concern since the creation of the Office fifty years ago. Addressing Indigenous disadvantage and discrimination behind bars were among the inaugural set of issues brought forward to the very first Correctional Investigator, Ms. Inger Hansen. The concerns of federally sentenced Indigenous peoples have been part of Office reporting ever since, though the calls for reform have become more pointed and more urgent with the release of each successive Annual Report. In the context of Canada’s troubled and entangled relationship with First Nations, Métis and Inuit, I am deeply frustrated and disappointed each time I report on reaching or surpassing yet another sad milestone in the unrelenting over-representation of Indigenous peoples under federal sentence.

Of course, my Office has not been alone in raising repeated alarm bells. As far back as 1999, Canada’s highest court, in the seminal decision of R. v. Gladue observed that Indigenous over-representation reflected a “crisis” in Canada’s criminal justice system. When the Office’s original Spirit Matters investigation was tabled as a Special Report to Parliament in March 2013 the rate of representation of Indigenous peoples in federal prisons stood at just under 25%. Ten years later, the rate stands at just under 33%, representing more than 4,200 Indigenous individuals. The steady and unabated increase in the disproportionate representation of Indigenous peoples under federal sentence is nothing short of a national travesty and remains one of Canada’s most pressing human rights challenges.

Proportions of Indigenous Peoples (First Nation, Métis, and Inuit) in Federal Custody

| % of Incarcerated Population | % of Incarcerated Indigenous Peoples | |

| First Nations | 22.6 | 70.1 |

| Métis | 8.6 | 26.8 |

| Inuit | 1.0 | 3.1 |

| TOTAL | 32 | 100 |

In releasing the original Spirit Matters report (2013), my predecessor, Mr. Howard Sapers, concluded that Indigenous-specific provisions of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA), articles of intention that were deliberately enacted by Parliament in 1992 to reduce over-representation, were “chronically under-funded, under-utilized and unevenly applied by the Correctional Service. In failing to fully meet Parliament’s intent … the federal correctional system perpetuates conditions of disadvantage for Aboriginal people in Canada.” As my updated findings make clear, a decade later and more than 30 years since the promulgation of the CCRA, the plight of Indigenous peoples behind bars has become steadily and progressively worse. Indeed, Canada’s correctional population is becoming disturbingly and unconscionably Indigenized .

Others have more thoroughly and exhaustively documented the circumstances and conditions that contribute to over-incarceration than can be captured here. Still, the general causes of over-representation are worth reiterating, both to understand how we got to this point, and, perhaps more importantly, how the legacy of colonialism continues to drive contemporary forms of racism, discrimination and apathy towards Indigenous peoples. Arising from the impacts of colonialism, the offending circumstances of incarcerated Indigenous peoples are often related to socio-economic, political and cultural disadvantages, inter-generational trauma and abuse, Residential Schools, the Child Welfare System, and the Sixties Scoop, among other factors. There are higher rates of poverty, substance abuse, and homelessness in Indigenous communities and lower rates of formal education and employment, among other factors, reflecting the intergenerational and present-day effects of colonialism and systemic racism. Problematic substance abuse is linked to high rates of poverty and unemployment, and family and community breakdown among First Nations, Métis and Inuit. These socio-economic and historical factors result in increased Indigenous contact (and re-contact) with Canada’s criminal justice system, a proverbial revolving door that keeps Indigenous peoples criminalized, marginalized and over-incarcerated.

Public awareness of the lingering effects of colonization – such as the intergenerational impacts of Residential Schools and the 60s scoop – has increased over the last decade since the release of the Office’s original Spirit Matters report. As documented last year, in Part I of our update on Spirit Matters , the federal government has recently recommitted to advancing reconciliation and building nation-to-nation relationships with Indigenous peoples. Other contemporary drivers of change include: the Calls to Action of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC); the Calls to Justice from the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG); and, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

The most relevant of these still mostly unanswered calls to action and justice to reduce Indigenous over-representation in the federal corrections system include:

- TRC Recommendation #30 – calls upon federal, provincial, and territorial governments to commit to eliminating the over-representation of Indigenous people in custody over the next decade.

- TRC Recommendation #35 – calls upon the federal government to eliminate barriers to the creation of additional Indigenous healing lodges within the federal correctional system.

- TRC Recommendation #37 – calls upon the federal government to provide more supports for Indigenous programming in halfway houses and parole services.

- TRC Recommendation #42 – calls upon the federal, provincial and territorial governments to commit to the recognition and implementation of Indigenous justice systems.

For its part, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) highlights the need to address the over-representation of Indigenous women in correctional facilities, now hovering around 50% of all women in-custody, and ensure culturally appropriate programming and services for incarcerated Indigenous women. The report calls upon the government to implement the Indigenous-specific provisions of the CCRA, including establishing more Healing Lodges, applying Indigenous social history factors in all decision-making concerning Indigenous women and 2SLGBTQQIA people; and ensuring the role of Elders in decision making for all aspects of planning for Indigenous women and 2SLGBTQQIA people.

Significantly, Office reporting on Indigenous Corrections over the last decade has either inspired or echoed virtually all of these directions for reform. Five years ago, in my very first Annual Report as Correctional Investigator, I suggested that the heavy lifting to address the enormity of the challenges of Indigenous over-incarceration had hardly begun, and that swifter, intentional and bolder actions were required:

[Correctional Service of Canada] and the Government of Canada must more fully devolve responsibility, but most of all resources and control, back to Indigenous people. In practice, this could entail a reallocation of spending to match the proportion of Indigenous people with a federal sentence. Reallocated funding would be re-profiled to create new community bed space capacity, especially in urban areas, and additional Section 81 facilities, truly Indigenized programs and services run by and for Indigenous communities. Loosening the levers and instruments of correctional (some might say) colonial control is consistent with the path toward reconciliation between Canada and its First Nations. Of course, devolution of correctional power will only happen if there is courageous and visionary leadership at the top of the Correctional Service – a vision and commitment that must be duly supported and directed by the Government of Canada.

The overall thrust and direction of these comments still apply. Making good on repeated calls and commitments to reduce Indigenous over-representation will undoubtedly require coordinated strategies and intentional actions. In fact, it seems readily apparent that Government of Canada efforts need to shift toward a focused Indigenous decarceration strategy, the general aims of which would include to:

- Create and utilize alternatives to incarceration for Indigenous peoples.

- Increase culturally relevant supports and services for Indigenous peoples under federal sentence.

- Reallocate significant resources and expenditures from penitentiary to community-based reintegration efforts, including community-run Healing Lodges (Section 81) at both minimum and medium security levels.

The Current Investigation

Ten Years Since Spirit Matters (Part II) is inspired and informed by renewed public awareness and interest in advancing reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. In revisiting and updating some of the key issues and findings of our original report, the objectives of the current investigation are somewhat more modest and relatively straightforward:

- Assess progress and developments in Indigenous Corrections since the release of Spirit Matters over a decade ago.

- Document the perspectives, experiences and voices of federally sentenced Indigenous peoples, parolees, staff and Elders/Spiritual Advisors.

- Conduct in-depth reviews of three signature interventions in the Correctional Service’s Indigenous “continuum of care” model – Healing Lodges, role and impact of Elders and Pathways initiatives.

Perhaps the most significant feature of the current investigation is our intention to publish first-hand accounts and insights of the Indigenous incarceration experience. Our interviewees and site visits were national in scope. Themes emerging from these engagements are informed by qualitative, quantitative and investigative methods and analysis. In conducting this investigation, the Office’s team of investigators and researchers conducted 223 interviews with incarcerated Indigenous individuals, Elders/Spiritual Advisors, Elder Helpers and assistants, Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) staff and management, Executive Directors of Healing Lodges and Community-based Residential Facilities. We visited or spoke to numerous individuals working or residing in 30 different federal penitentiaries, CSC-run and Section 81 Healing Lodges across the country.

Further, the Office conducted a series of engagements with a number of national and local Indigenous organizations. This was an effort to exchange knowledge and, more importantly, for the Office to listen and learn from the perspectives of these organizations who have a unique vantage point on the issues that affect Indigenous peoples who come through the correctional system. Consultations took place with the following organizations: Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, Native Women’s Association of Canada, Métis National Council, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, Native Counselling Services of Alberta, and the John Howard Society of Manitoba.

The report itself is structured and presented in three distinct parts, each corresponding to the substantive area under investigation:

- Unfulfilled Promises: Investigation of Healing Lodges in Canada’s Federal Correctional System

- A Straight and Narrow Road: Investigation into the Pathways Initiative in Federal Corrections

- Investigation of the Role and Impact of Elders in Federal Corrections

As might be expected, the range and diversity of experience and the feedback we gathered from semi-structured and open-ended investigative interviews was resoundingly insightful, often profound, and, at times, emotional and difficult to process. That said, the sorting and summaries of interview notes led to a compilation and convergence of themes pointing to several areas of systemic concern. For instance, in the Healing Lodge context, we recorded that there continues to be too few Healing Lodges to meet their original vision and intent. What has resulted is a two-tier Healing Lodge system, where community-run (Section 81) lodges continue to be pitted against those that are state-run, in constant competition for residents, funding, staff, and authority. We heard that while community-run lodges face numerous challenges, they are a largely under-utilized yet promising model, closer to the original vision, in which corrections should make greater investment.

From Pathways interviewees we learned about the high threshold for participation, how most institutions are non-compliant with key elements of the initiative, and the lack of corporate recognition for the hard work achieved along one’s Healing Path. And from Elders working inside CSC facilities we heard about their experience in trying to bridge Western and Indigenous understandings of behavioural change and healing in a correctional context. Elders related narratives and experiences of trying to de-colonize corrections and to provide advice and counsel to their ‘relatives’ behind bars. They shared immediate and personal stories about struggling to have their own voice heard, represented and respected within CSC decision-making circles.

Our update of Spirit Matters ten years later represents a two-year investment of Office resources. In distilling both what we heard and witnessed, cumulative findings from a series of investigations include:

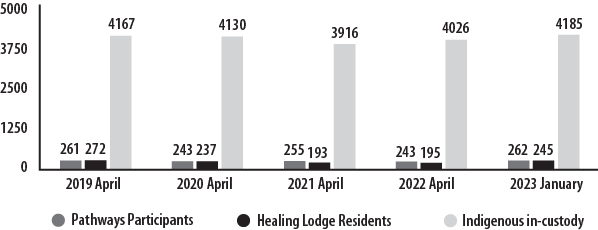

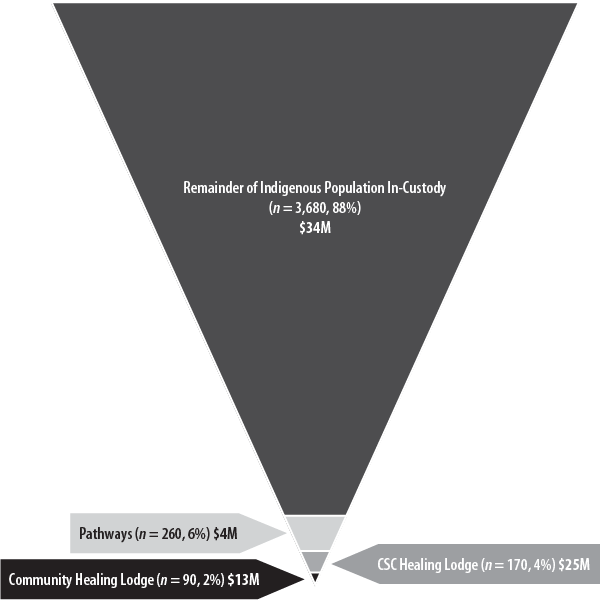

- Pathways interventions inside federal penitentiaries and Healing Lodge placements in the community serve too small of an Indigenous cohort to have any meaningful or measureable impact on Indigenous rates of over-representation.

- Lack of Indigenous cultural awareness and competence at all levels within CSC undermines its capacity to deliver on its so-called Indigenous First strategy.

- CSC’s pan-Indigenous approach to Indigenous Corrections erases significant historical and cultural differences between and among Indigenous peoples and First Nations, Métis and Inuit leading to significant limitations, gaps and omissions.

- Narrow and restrictive eligibility criteria for admission to Pathways and most Healing Lodge placements effectively prohibits access to all but a minority of Indigenous peoples under federal sentence.

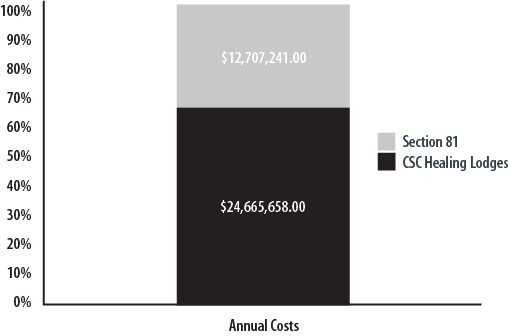

- State-run Healing Lodges are funded, staffed, resourced and occupied at significantly higher levels than their Indigenous-run Section 81 counterparts.

- The contributions of Elders/Spiritual Advisors working inside federal institutions are under-supported, under-valued, under-reported and under-appreciated by their employer.

- CSC’s repeated attempts to “transform” its Indigenous Corrections framework and strategies, including its latest iteration (National Indigenous Plan), have yielded few appreciable gains ten years after the original Spirit Matters investigation.

- CSC has failed to innovate and take full advantage of Indigenous-specific provisions of the CCRA intended to address Indigenous over-representation.

- The Service lacks clear public accountability indicators for Indigenous Corrections and fails to meaningfully report on performance indicators and progress in reducing Indigenous over-representation.

- Total discretionary spending on Indigenous Initiatives within CSC, inclusive of Healing Lodges, Pathways and Elders, amounts to $75M annually, representing approximately just 3% of its total annual budgetary allocation.

Though I acknowledge that CSC does not solely control or decide who enters federal penitentiaries, it does control access to the levers of reintegration, rehabilitation and eventual release from prison. On this very same and significant point, the Office’s original 2013 Spirit Matters report concluded, “CSC has failed to make the kind of systemic, policy and resource changes that are required in law to address factors within its control that would help mitigate the chronic over-representation of Aboriginal people in federal penitentiaries.” Unfortunately, in the present context I found no divergent or compelling evidence to change or counter this conclusion. Increasing rates of Indigenous representation in federal prisons, the persistently high number of Indigenous peoples who only gain release from prison at mandatory or warrant expiry, and the overall disparate and distressing outcomes on nearly every measure of correctional performance belies the very stubborn reality that Canada’s federal correctional system continues to fail Indigenous peoples.

Until very recently, CSC has been somewhat circumspect to speak directly or acknowledge any role or responsibility in contributing to or addressing Indigenous over-representation in federal corrections. Ministerial and Commissioner mandate letters now speak more candidly and constructively to reducing over-representation, setting Government expectations and establishing CSC priorities in these matters. The appointment of the first Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections in Canada is a welcomed, if long overdue step in acknowledging the need for change and reform. It is my expectation that Government action and this appointment will establish a senior and dedicated point of contact, accountability, and leadership on Indigenous Corrections within CSC that has been frankly missing for far too long. It is also my hope that this report provides inspiration in renewing CSC’s relationship with Indigenous peoples.

At the same time, it is important to acknowledge that there are limitations to what may be accomplished within the federal correctional system as it currently exists. Penitentiaries are historically and inherently colonial institutions. One of Canada’s first and most imposing symbols of colonial power, Stony Mountain Penitentiary in Manitoba, began operations in 1877 and is now Canada’s oldest and largest continuously operating penitentiary. It was used to imprison Indigenous peoples taking part in the North-West Rebellions of 1885. Today it still holds an overwhelming percentage of Indigenous peoples. Given this history and legacy, to expect “healing” to take place inside the walls of some of these unmistakably Indigenous facilities seems a somewhat forced and paternalistic conceit.

It bears noting that today, like yesteryear, most Indigenous persons serving a court sentence in a federal penitentiary are not involved in any of CSC’s Indigenous “continuum of care” interventions. As documented in this report, selection and participation in CSC’s signature continuum of care initiatives, such as Pathways and Healing Lodges, seem reserved for only the most motivated, compliant and engaged Indigenous person. The overwhelming majority of Indigenous peoples in CSC custody do not benefit from early or timely conditional release and reintegration, contributing to shockingly high rates of reoffending and returns to prison. The system is simply and largely unresponsive to their needs, realities and potential. Even my Office had to stretch to reach these largely forgotten and abandoned people, some accounts of which are embedded throughout this report. They are part of the unheard, unseen, and often excluded Indigenous majority languishing inside federal prisons.

While CSC must be held accountable to defining and meeting measurable targets to improve outcomes for Indigenous peoples in corrections, the inherent limitations of the corrections system also point to the need to support Indigenous criminal justice efforts and systems outside federal corrections. On the road to ameliorating over-representation, there is not just one path forward, but many, and the more promising among them may actually reside outside the reach of federal corrections.

Unfulfilled Promises: Investigation of Healing Lodges in Canada’s Federal Correctional System

“My life chances as a young Indigenous boy were not handed to me. I was in the 60s scoop, I didn’t have an outlet for my anger. At one point, I made a decision that I’m gonna beat these walls, they were not going to beat me – I knew I had the capability to do good for this world. At first, I couldn’t get to the healing lodge because of my scores. They never actually explained to me why. Then I had to train my parole officer on how to do my transfer. I had to know my stuff because my PO was so green and the transfer was in his hands... If you want to make an impact. It’s about ceremonies. It’s that unseen connection, we understand it’s there…My recommendation is: Believe in us.”

– Former Healing Lodge Resident

Introduction and Context

The origins of Healing Lodges in the Canadian correctional system can be traced back to the late 1980s, when prison and community advocates, including the Native Women’s Association of Canada, the Aboriginal Women’s Caucus of the Elizabeth Fry Society, and the Native Sisterhood, proposed the concept of a Healing Lodge as a way forward towards decolonizing the correctional system. Not simply as an alternative to mainstream prisons, these women put forward a vision for Healing Lodges, founded on the Medicine Wheel and the Four Directions in the Circle of Life – Spiritual (East), Emotional (South), Physical (West) and Mental (North) – guided by the original teachings, ceremony, and instructions. Healing Lodges were envisioned as places where Indigenous peoples serving federal sentences could feel safe to heal, on the land, ideally near pure natural running water, with the support from Elders, community, and families. Most importantly, they would be located away from the oppressive and punitive penitentiary environment.

Section 81 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act

81. (1) The Minister, or a person authorized by the Minister, may enter into an agreement with an Indigenous governing body or any Indigenous organization for the provision of correctional services to Indigenous offenders and for payment by the Minister, or by a person authorized by the Minister, in respect of the provision of those services.

(2) Notwithstanding subsection (1), an agreement entered into under that subsection may provide for the provision of correctional services to a non-Indigenous offender.

(3) In accordance with any agreement entered into under subsection (1), the Commissioner may transfer an offender to the care and custody of an appropriate Indigenous authority, with the consent of the offender and of the appropriate Indigenous authority.

After years of discussions and planning, the first federal Healing Lodge to open was Okimaw Ohci, in November of 1995, on Nekaneet First Nation in Saskatchewan. This marked the beginning of what many optimistically hoped would usher in a new era for Indigenous corrections. It would be one that acknowledged that the over-representation of Indigenous peoples in the prison system was in-part a consequence of the failures of conventional correctional practice. Furthermore, the enactment of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act (CCRA) in 1992, which included specific provisions relating to the custody, care, and release of Indigenous persons serving federal sentences (e.g., Section 81) allowed the Minister to enter into agreements with Indigenous communities for the provision of correctional services. While these agreements do not transfer jurisdictional responsibilities for corrections, the manner in which this section of the Act was written enabled a broad degree of control by Indigenous communities or organizations, or at least participation in, an individual’s full sentence. Furthermore, it gave communities the flexibility to negotiate the number and profile of those individuals they were prepared to accept into their communities. It also allowed for services and programming, including care and custody, to be negotiated and delivered by Indigenous communities and organizations for payment by the Crown. Given that Section 81 does not stipulate how Indigenous communities are to manage individuals, the flexibility allowed for the funding of Healing Lodges as either facility-based centres, such as Healing Lodges, or through “non-facility” funding agreements with Indigenous communities that accept to provide custody, programming, and care to individuals, without a formal, brick-and-mortar healing centre.

In the decade that followed the opening of Okimaw Ohci, an additional seven Healing Lodges for men would open across the country, with two additional Healing Lodges for women established in 2011 and most recently in 2019. Today, there are a total of ten Healing Lodges available to individuals serving federal sentences – four that are funded and managed by CSC (i.e., state-run) and six that are funded by CSC, but managed by a community partner organization through a Section 81 Agreement (i.e., Community-run). As will be documented later in this report, there are only 139 Healing Lodge beds managed by Indigenous communities and many of those are under-utilized.

Spirit Matters (2013)

Twenty years after the enactment of the CCRA, by way of Spirit Matters , this Office assessed the extent to which CSC had fulfilled the government’s intent, with specific interest in the use of Section 81 agreements, which along with other provisions, was intended to reduce the over-incarceration of Indigenous peoples. The findings from the 2013 investigation revealed that CSC had not met Parliament’s intent with respect to Section 81 of the CCRA, which in turn, had contributed to the deterioration of the correctional outcomes and increases in the over-representation of Indigenous peoples in federal prisons. Specifically, the investigation found that CSC had not sufficiently exercised Section 81, with only five agreements having been put in place in those twenty years. Furthermore, the investigation revealed other major gaps, barriers, and vulnerabilities, including:

- the short-term and temporary nature of contribution agreement cycles with community-run Healing Lodges;

- major discrepancies in funding between CSC-run and Section 81 lodges, with lower funding to the community-run lodges;

- low community acceptance of Healing Lodges;

- restrictive eligibility criteria applied at Section 81 Healing Lodges; and,

- significantly poorer working conditions and salaries at Section 81 Healing Lodges compared to CSC-run lodges.

Since the opening of the first Healing Lodge, this Office has made ten formal public recommendations, including those issued through Spirit Matters , specifically on the need for more, better-funded community-run Healing Lodges that more closely align with the original vision. In the years since Spirit Matters , through the findings, recommendations, and calls-to-action of various reports, parliamentary studies, and key commissions, such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls , there has been a groundswell of recognition and pressure on the government to increase access to community-run, Section 81 Healing Lodges.

Current Investigation

The current investigation examined what progress has been made in the last ten years since Spirit Matters was tabled in parliament. Through a combination of documentation review, data analysis, site visits, and interviews with 50 current and former Healing Lodge staff and residents, we gathered invaluable insights. The following are key themes, findings, and recommendations that emerged in the course of the investigation. While this investigation reveals that many of the fundamental challenges and deficiencies identified in Spirit Matters remain today, this Office would like to acknowledge and express gratitude to the many individuals – Healing Lodge staff, residents, and members of the community alike, who were willing to share their experiences and perspectives. Furthermore, we acknowledge the important work of the people at the front lines. These individuals, who largely shoulder the daily challenges, with limited resources, and are often required to generate creative, local solutions in order to create meaningful differences in the lives of the people with whom they work and support.

OCI Public Recommendations on Healing Lodges

1995/96 – Recommendation #15: That the Commissioner of Federally Sentenced Women vigorously exercise the authority provided for within Section 81 to expand the provision of correctional services provided by aboriginal communities to ensure that timely conditional release is a viable option.

2005/06 – Recommendation #6: I recommend that in the next year the Correctional Service build capacity for, and increase use of, section 84 and section 81 agreements with Aboriginal communities.

2009/10 – Recommendation #21: The Service should increase its use of Sections 81 and 84 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act to their fullest and intended effect.

2012/13 – Recommendation #2: CSC should develop a long-term strategy for additional Section 81 agreements and significantly increase the number of bed spaces in areas where the need exists. Funding for this renewed strategy should either be sought from Treasury Board or through internal reallocation of funds and amount to no less than the $11.6 million re-profiled in 2001 and adjusted for inflation.

2012/13 – Recommendation #3: CSC should re-affirm its commitment to Section 81 Healing Lodges by: (a) negotiating permanent and realistic funding levels for existing and future Section 81 Healing Lodges that take into account the need for adequate operating and infrastructure allocations and salary parity with CSC, and (b) continuing negotiations with communities hosting CSC-operated Healing Lodges with the view of transferring their operations to the Aboriginal community.

2012/13 – Recommendation #5: CSC should re-examine the use of non-facility based Section 81 agreements as an alternative to Healing Lodges, particularly in those communities or regions where the number of Aboriginal offenders may not warrant a facility. The results of this examination would form part of CSC’s overall strategy for Section 81.

2012/13 – Recommendation #10: CSC should work with Aboriginal Christian, Inuit and other identifiable communities to develop Section 81 agreements where warranted.

2016/17 – Recommendation #12: CSC review its community release strategy for Indigenous offenders with a view to increase the number of Section 81 agreements to include community accommodation options for the care and custody of medium security inmates; and, address discrepancies in funding arrangements between CSC and Aboriginal-managed Healing Lodges.

2017/18 – Recommendation #13: CSC re-allocate very significant resources to negotiate new funding agreements with appropriate partners and service providers to transfer care, custody and supervision of Indigenous people to the community. This would include creation of new section 81 capacity in urban areas and section 84 placements in private residences. These new arrangements should return to the original vision of the Healing Lodges and include consultation with Elders.

External Recommendations on Healing Lodges in the Ten Years since Spirit Matters

Truth and Reconciliation Commission – Calls to Action (2015).

Recommendation #35: We call upon the federal government to eliminate barriers to the creation of additional Aboriginal Healing Lodges within the federal correctional system.

Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security, Indigenous People in the Federal Correctional System (June 2018)

Recommendation #2: That Correctional Service Canada increase the number of agreements with Indigenous communities under section 81 of the CCRA.

Recommendation #3: That the Government of Canada increase funding to Indigenous communities for agreements under section 81 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act in order to address the funding gap between healing lodges operated by Indigenous communities and those operated by the Correctional Service Canada.

Standing Committee on the Status of Women, A Call to Action: Reconciliation with Indigenous Women in the Federal Justice and Corrections Systems (June 2018)

Recommendation #66: That the Government of Canada, in consultation with Indigenous peoples and communities, provide additional resources to Correctional Service Canada and Indigenous communities to increase the use of sections 29, 81 and 84 of the CCRA.

National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls – Calls to Justice (2019)

Recommendation #14.1: We call upon Correctional Service Canada to take urgent action to establish facilities described under sections 81 and 84 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act to ensure that Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people have options for decarceration. Such facilities must be strategically located to allow for localized placements and mother-and-child programming.

Recommendation #14.2: We call upon Correctional Service Canada to ensure that facilities established under sections 81 and 84 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act receive funding parity with Correctional Service Canada-operated facilities. The agreements made under these sections must transfer authority, capacity, resources, and support to the contracting community organization.

Standing Senate Committee on Human Rights – Human Rights of Federally-sentenced Persons (2021)

Recommendation #19: That the Correctional Service of Canada increase its use of section 81 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act with a view to ensuring that federally-sentenced persons, particularly federally-sentenced Indigenous women and men, are able to build and/or maintain ties with their families, communities and culture.

Recommendation #51: That the Correctional Service of Canada increase the number of section 81 agreements by raising awareness of this section and guiding communitiesin 2001 and adjusted for inflation.

1. The Issue of Too Few Community-run Healing Lodges Remains

As raised in Part 1 of this investigation last year, the insufficient number of Healing Lodges and bed spaces has been a long-standing issue, one that has become more pressing as the over-representation of Indigenous peoples has continued to increase. In at least six different public reports, this Office has made recommendations to the Service that they should increase the use of Section 81 agreements and create more Healing Lodges for federally-sentenced persons. As described in Spirit Matters , the shift in momentum that occurred in the early 2000s, with CSC moving away from investing in and expanding the Healing Lodge model, to instead re-profiling Healing Lodge funds to prison-based interventions, remains as true today as it was ten years ago.

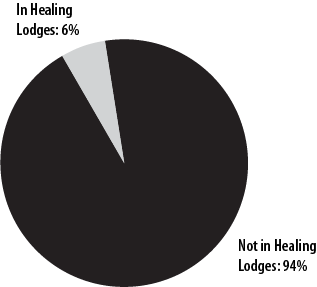

Over the last ten years, the growth in the Indigenous prison population has far out-paced the growth of Healing Lodges. Specifically, while the number of incarcerated Indigenous individuals has increased by nearly 700, the number of Healing Lodges has increase by only one (i.e., Eagle Women’s Healing Lodge in Winnipeg, in 2019). Furthermore, the number of beds in community-run Healing Lodges has increased by a total of 53. At present, with only ten Healing Lodges in Canada, there is a total of 389 beds for federally-sentenced individuals (271 for men and 118 for women). Of particular concern however, is how few of these beds are in community-run Healing Lodges. While there are more Section 81 Healing Lodges, they in fact only account for 35% of the total bed count. There are therefore only 139 Healing Lodge beds managed by Indigenous communities.

Proportion of Incarcerated Indigenous Population in Healing Loges

Given the large number of Indigenous individuals in federal custody (4,216), the number of Healing Lodge beds available today could only ever accommodate a maximum of 9% of the Indigenous in-custody population. Put differently, even under a full-occupancy scenario, 91% of incarcerated Indigenous persons would not have the option, even if they are eligible, but to remain incarcerated in a mainstream prison system. With the current complement of Healing Lodges, and only 6% of incarcerated Indigenous individuals currently severing a portion of their sentences in a Healing Lodge, the vast majority of Indigenous persons serving federal sentences will never have access to, or benefit from a Healing Lodge, let alone a community-run Healing Lodge.

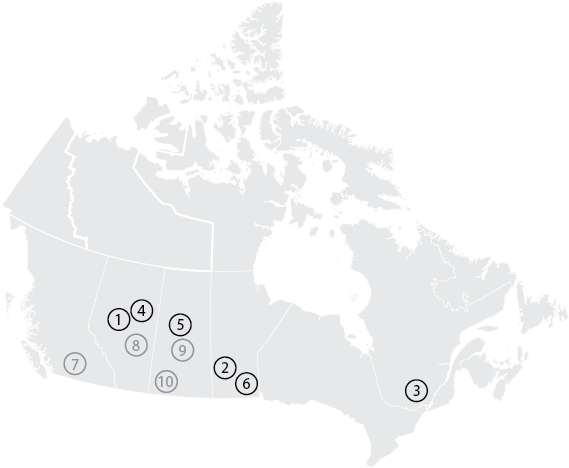

Location of CSC-run and Section 81 Healing Lodges in Canada

Table 1. Names, Locations, and Designations of the Ten Healing Lodges

| Healing Lodge | CSC-run or Section 81 | City, Province |

| 1 - Stan Daniels Healing Centre | Section 81 | Edmonton, Alberta |

| 2 - O-chi-chak-ko-sipi Healing Lodge | Section 81 | Crane River, Manitoba |

| 3 - Waseskun Healing Centre | Section 81 | St-Alphonse-Rodriguez, Quebec |

| 4 - Buffalo Sage for Women | Section 81 | Edmonton, Alberta |

| 5 - Prince Albert Grand Council Healing Lodge | Section 81 | Wahpeton First Nation, Saskatchewan |

| 6 - Eagle Women’s Healing Lodge | Section 81 | Winnipeg, Manitoba |

| 7 - Kwìkwèxwelhp Healing Village | CSC-run | Harrison Mills, British Columbia |

| 8 - Pê Sâkâstêw Centre | CSC-run | Maskwacis, Alberta |

| 9 - Willow Cree Healing Centre | CSC-run | Duck Lake, Saskatchewan |

| 10 - Okimaw Ohci Healing Lodge | CSC-run | Maple Creek, Saskatchewan |

The gaps in the Healing Lodge model are evident not only by the insufficient number of lodges and beds, but also by how they are distributed across the country. As was the case ten years ago, currently, there are still no Healing Lodges in the Ontario and Atlantic regions, none in the North, and no community-run Healing Lodges in the Pacific region. Given that the Ontario region has the second largest number of federally-incarcerated Indigenous persons, and is where many of these individuals have their families and home communities, there is clearly still a significant need for Healing Lodges in this region. For Indigenous women, all three Healing Lodges for women are located in the Prairie region. While there is indeed a considerable need in the prairies, where more than half of incarcerated Indigenous women are located, women from communities outside of the prairies – particularly Ontario and the Pacific regions – have no options to reside at a Healing Lodge closer to their families and home communities. This, in turn, forces many Indigenous women to choose between an isolated traditional healing path far away from home or to be close to family in a CSC prison setting.

With essentially no progress made on expanding the Healing Lodges in remote communities, it is unsurprising, albeit disappointing, that there has been little progress on establishing new Section 81 agreements, be they facility or non-facility-based, with organizations in urban centers where there is arguably the greatest need. The reality is that most individuals will seek release to urban centers. It affords them increased opportunities to access employment, educational or vocational training, and in many cases can facilitate access to their families and children that may otherwise prove to be more difficult and costly in remote communities. One of the benefits of Section 81 is that it also allows for the creation of non-facility agreements, in urban or rural communities. At the time Spirit Matters was written, there had been only two communities with which CSC had entered into non-facility agreements (in 1999 and 2001) under Section 81; however, at the time, records showed that the transfer of only one individual had ever been completed. Requests made to the Service seeking the number of non-facility or Exchange of Service Agreements (ESA) of Indigenous individuals under Section 81 over the last decade revealed that there have been no additional non-facility agreements or ESAs with communities or organizations under Section 81.

In July 2022, CSC promulgated “new” policy documents to guide the process for Section 81 agreements. By dividing what had been Commissioner’s Directive (CD) 541 into now two separate CDs, along with guidelines, the Service created CD 541 – Interjurisdictional Exchange of Service Agreements and a new CD 543 – CCRA Section 81 Agreements . 21 The goal, particularly for the latter, was to provide internal “direction for reaching mutually developed formal proposals with interested Indigenous communities and organizations…allowing CSC to be better positioned to support Indigenous communities interested in section 81 agreements, including those with existing section 81 agreements.” While the nature of the changes appear to be largely in the clarification and definition of roles, creation of new timeframes, etc., time will tell whether these new policy documents in fact translate into new Section 81 agreements – be they agreements with Healing Lodges, or as non-facility agreements – with communities.

Over the course of this investigation, this Office sought updates on any plans currently underway to create new Healing Lodge agreements. In April 2023, CSC provided a response indicating that, “no formal submissions are being considered but all regions are actively engaging possible partners to enhance Section 81 opportunities”. Meanwhile, in a March 31st, 2023 in response to an Access to Information request by Aboriginal Peoples Television Network (APTN) News, the Service shared with them that they are “negotiating with 15 communities to create healing lodges for Indigenous prisoners”. 22 Setting aside the perplexing secrecy on the part of the Service to share such details with our Office, again, a monitoring of how – or if – these negotiations progress will reveal how invested the Service is in expanding the use of Section 81 agreements.

In May 2022, the Minister of Public Safety issued a mandate letter to the Commissioner of Corrections, the very first objective of which directs the Commissioner to: “Prioritize working with and funding Indigenous organizations and communities to create additional section 81 and 84 agreements in accordance with theCCRAto ensure that Indigenous offenders have access to culturally-relevant programming and supports in the community.”

This Office is aware that there are a myriad of challenges and barriers to establishing agreements with Indigenous communities or groups. Some are reluctant to accept individuals who committed serious offences into their communities. Others see great value in the Healing Lodges, but are deterred by the bureaucratic and resource-intensive application processes, or by the understandably unappealing prospect of negotiating with a government agency that has played a central role in the mass imprisonment of Indigenous peoples. While communities indeed play an active role in the Section 81 process, they should not be made to wear the blame for the lack of progress on the creation of new agreements over the last decade. The Service’s lack of meaningful and coordinated community outreach and engagement is beyond excuse, given the trajectory of over-representation and the dozens of calls-to-action on this very issue. In prioritizing prison-based initiatives, the Service’s demonstrable inertia regarding Section 81 reveals an unwillingness to utilize it to its fullest extent, even at the behest and direction of the Minister. An agency that has otherwise shown both the interest and ability to think ambitiously about custodial practice must be expected to apply such thinking to community-based alternatives, particularly when they already have such tools for the job sitting idly in their toolbox.

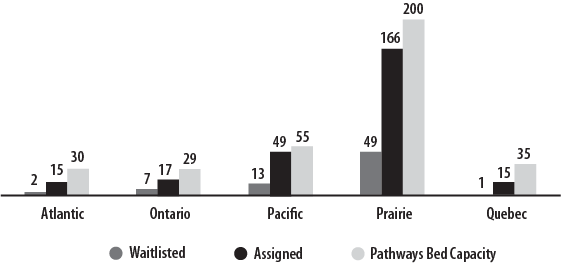

2. Vacancy Rates Remain High at Healing Lodges