Office of the Correctional Investigator Annual Report 2021-2022

June 30, 2022

The Honourable Marco Mendicino

Minister of Public Safety

House of Commons

Ottawa, Ontario

Dear Minister,

In accordance with section 192 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Act, it is my privilege and duty to submit to you the 49th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator.

Yours respectfully,

Ivan Zinger, J.D., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

Table of Contents

Correctional Investigators Message

National Updates and Significant Cases

2. Correctional Service of Canada’s Drug Strategy

4. Structured Intervention Units

5. Over-representation of Indigenous Women in Secure Units (Maximum Security)

National Level Investigations

1. Update on the Experiences of Black Persons in Canadian Federal Penitentiaries

2. Restrictive forms of Confinement in Federal Corrections (Male Maximum-Security Penitentiaries).

3. Ten Years since Spirit Matters : Indigenous Issues in Federal Corrections (Part I)

Correctional Investigator’s Outlook for 2022-23

Ed McIsaac Human Rights in Corrections Award

Annex A: Summary of Recommendations

Response to the 49th Annual Report of the Correctional Investigator

Correctional Investigator's Message

Dr. Ivan Zinger,

Correctional Investigator of Canada

It was no accident of history that my Office was created nearly 50 years ago, in 1973, amidst a series of seemingly uninterrupted prison riots, hostage takings, murders, mayhem and maladministration that nearly brought Canada’s Penitentiary Service, as it was then known, to its knees. The Commission of Inquiry set up to get to the bottom of this unprecedented period of revolt and unrest in Canada’s prison system recognized the value of providing federally sentenced people with an independent and external redress system for the airing and resolution of legitimate grievances. The first Correctional Investigator, Ms. Ingrid Hansen, took up her role in June 1973. Half a century later, my Office still provides a necessary outlet for the airing of individual and systemic prisoner complaints. My Office continues to carry out independent monitoring and oversight of Canada’s federal correctional system, conducting investigations, reporting findings and issuing recommendations with the hope of effecting lasting change and positive reform.

As an oversight body, my ability to influence, effect change or persuade an alternative course of action is tied to the quality, thoroughness, relevance, and integrity of the investigations that my Office conducts. In such matters, the Office’s influence relies on a mixture of discretionary and obligatory powers, simultaneously bounded and contingent on the issues identified and brought forward in public reporting. It is certainly within my responsibility to inform the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) when I think that their boat is listing or possibly in danger of sinking, but it is not within my remit to build them a better or more leak-proof vessel. To the point of the matter, my ability to influence policy or practice within CSC incorporates those areas of systemic or individual concern that I raise in my Annual Reports, bring before Parliament, or choose to occasionally raise with the media.

It is true that, on occasion, I may vent my frustration in the media or express public dissatisfaction or disappointment with CSC and its proclivity to deflect, obstruct or defend itself against criticism. While my findings, particularly those of a systemic nature, are sometimes ignored or not acted upon by CSC, I am proud of the fact that the larger body of the Office’s work does not go unnoticed by many others, including academics, lawyers, media, Parliament, other interested Canadians and vested stakeholders. From national Commissions of Inquiry, like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, to reports from Parliamentary Standing Committees, and in universities and courtrooms across the land, OCI recommendations and reports are frequently cited to inform, to teach, to instruct, and yes – from time to time – to litigate.

For very good reason, the statutory powers and authorities that protect and ensure my functional independence from CSC and the Minister of Public Safety also provide that I am not a compellable or competent witness in any legal proceedings. I cannot be subpoenaed to appear before a judge or be drawn into the courtroom to provide expert evidence or first-hand testimony. That said, the content and context of Office reporting are frequently used by the courts or counsel, often entered as background information or even evidence for consideration in both individual and class-action suits. Office reporting on the over-representation and disparate outcomes of Indigenous (Gladue factors and actuarial risk assessments) or Black persons (cultural assessments) in federal corrections, for example, is often taken under consideration during sentencing. The long and contorted legal battles and constitutional challenges to end solitary confinement in Canada relied on evidence, in part, documented in OCI findings over many, many years of reporting on this issue.

The vitality, relevance, and strength of the Office lies in its ability to provide witness, to document accurately, impartially and without fear of reprisal or dismissal. We can enter and inspect federal prisons unfettered and we can demand production of any document without delay or redaction. We endeavour to accurately report out on what really goes on behind those imposing walls. We speak truth to power. I am justifiably proud of the fact that our reporting is used to inform legislation and legislators alike. Office recommendations, reports and findings often make their way into Government criminal justice priorities, speeches from the throne, Ministerial or Commissioner Mandate letters. A recent reference in the Public Safety Minister’s mandate letter from the Prime Minister – that he “work to address systemic racism and the over-representation of Black and racialized Canadians and Indigenous Peoples in the justice system” – reflects on a Government priority that can be traced back to more than a decade of Office reporting. Moreover, our 2019-20 national investigation on sexual coercion and violence behind bars ( A Culture of Silence ) was also referenced in the Minister’s mandate letter in direction from the Prime Minister that he “consider how to ensure that federal correctional institutions are safe and humane environments, free from violence and sexual harassment, and promote rehabilitation and public safety.” Our reporting is often referenced by UN Special Rapporteurs – internationally recognized human rights experts who periodically report on prison conditions or the treatment of vulnerable groups behind bars. OCI citations can also be found in government reports to UN oversight bodies established to monitor Canada’s compliance with international human rights treaty obligations.

While I would, of course, like to see more acceptance of my recommendations and recognition of my oversight role within CSC, it is not from lack of trying. As an ombudsman, my powers are limited to making recommendations. I cannot compel the Service to accept my findings or implement my recommendations. CSC’s only legal obligation is to respond within a reasonable time frame to my recommendations. I have little control over the manner, method, content, veracity or commitment of CSC’s responses.

Truth be told, it can be frustrating to receive a CSC response that answers one of my reports or recommendations with “policy says this…” or “policy directs that…” In response to any given report, up to half of my recommendations may be answered with citations from CSC’s extensive catalogue of Commissioner’s Directives (CD). Within CSC, the ever-expanding collection of CDs has somehow attained the same status as the law, which it is supposed to provide meaning. My investigators are quite well versed in what policy does or does not instruct. The reason why we bring forward these matters in the first place is usually because we have found some non-compliance with the policy measure in practice, be it misinterpretation, misapplication, or sometimes, even a gap in policy. It is what my Office does: we monitor and ensure compliance with law and policy. An act of omission or finding of non-compliance cannot be saved by the fact that a Commissioner’s Directive already exists, can be cited word-for-word, or is actually intended to mean something else. To answer a finding of non-compliance with a policy citation is circular and dismissive of the matter in question. It is not a response.

It is said that advice is often ignored at one’s own peril. To extend this metaphor, it could be said that findings and recommendations reissued by my Office are dismissed, not acted upon or set aside at CSC’s peril. This year’s report incorporates a number of issues of national significance or concern that have been raised throughout the reporting period, often in correspondence, institutional visits, or bilateral meetings and exchanges with CSC at all levels within the organization. They are usually not new issues, but rather areas of unresolved, unaddressed or updated concern that remain under active investigation. In many cases, the same recommendations from previous reports are repeated verbatim or reissued with some new language. Some of these updates and their respective reporting histories included in this year’s report are:

- Prohibition on the use of dry cell placements beyond 72 hours (recommendation first made in the Office’s 2011-12 Annual Report, repeated in 2018-19, and reissued in 2021-22).

- A prison needle exchange program (PNEP) that, based on low participation rates, exists more in name than practice (initially reported in the Office’s 2018-19 Annual Report).

- Dysfunction at Edmonton Institution (successive Annual Reports).

- Over-representation of Indigenous women in maximum-security units (many Annual Reports, and a section 180 Report and Notice to the Minister in June 2018).

- Overly restrictive criteria that systematically restrict or discriminate against Indigenous women’s participation in the residential Mother-Child Program (first raised in the 2009-10 Annual Report).

- Lack of prisoner seatbelts in CSC’s escort vehicles (first raised in the Office’s 2016-17 Annual Report).

I could easily list more issues and their reporting histories above, but I think the point has been sufficiently made. Notwithstanding the fact that corrections fall within an area of public policy that is stubbornly resistant to reform and change, there are many reasons why, in the course of my work, it is often the case that I feel compelled to renew or update findings or reissue recommendations over and over again. For those still counting, it is why my predecessor and I have considered it necessary to repeat the recommendation for CSC to appoint a Deputy Commissioner for Indigenous Corrections more than ten separate times in more than twenty years of dogged reporting on this issue. It is also why so many of the themes and topics included in this year’s report are not new issues per se, but rather involve a different take on a matter of concern that reaches back years or even decades of Office reporting.

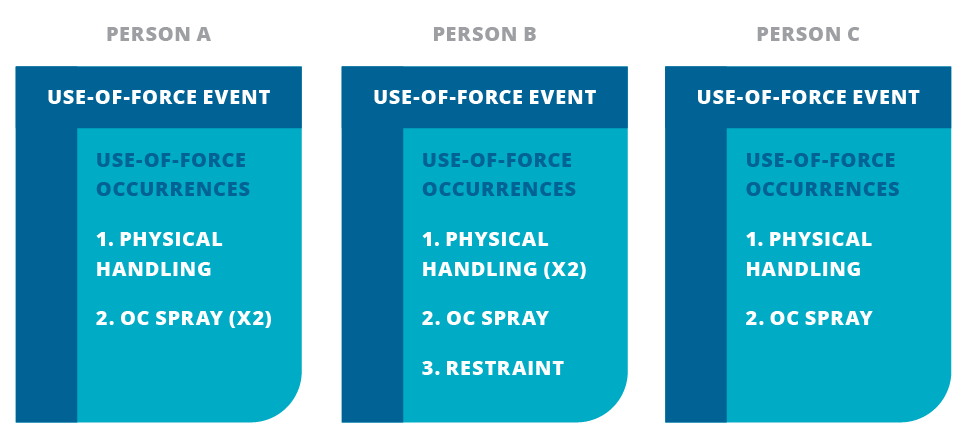

In any given year, there are, in fact, very few issues that could be considered new or that have never been reported by my Office. Medical Assistance in Dying (MAiD) was perhaps the last truly new issue in corrections that my Office has addressed, but even then MAiD was simply an extension of legislation to a largely forgotten class of incarcerated people who still remain deprived of deciding how, when and where they can choose to end their lives with respect and dignity. Other more “modern” issues and concerns in contemporary corrections – gender identity and expression, sexual coercion and violence behind bars, impact of COVID-19 measures and restrictions on prison populations, growing old(er) behind bars, over-representation of Black persons in use of force incidents – are “new” or interesting only insofar as reporting on these topics manage to reach the light of day.

I understand as well as anyone might that systemic change in corrections does not come easily or quickly. CSC and the Department of Public Safety are only now beginning to take measure and substantively address the prevalence of sexual coercion and violence behind bars. Five years after gender-based discrimination was added to the prohibited grounds of the Canadian Human Rights Act, a new standalone Commissioner’s Directive has just recently been promulgated. While these policy initiatives are responsive to Office reporting in these areas, there are any number of other issues where correctional policy and practice (for example, CSC’s zero-tolerance approach to drug use and possession behind bars) is considerably out of step with the times.

On this last point my reporting on promising harm reduction measures like a safe consumption site (Overdose Prevention Service) and needle exchange service behind bars being actively subverted by zero-tolerance security practises merely scratches the surface of the substantive reforms required. I point out that the last time CSC updated its National Drug Strategy was in 2007. Canadian policy on simple drug possession and consumption has moved dramatically since then, yet CSC culture remains mired in a prohibitive and repressive mindset. Maintaining a zero-tolerance approach to drugs that relies on ever more intrusive detection, disciplinary and repressive measures – strip-searches, body cavity scanning, cell searches, charges, urinalysis testing – is a costly game of diminishing returns. If a person is so desperate, indebted or addicted enough to the point of concealing drugs in body cavities with potentially life-threatening consequences, then surely this level of desperation should point us to consider other less intrusive, evidence-based and compassionate approaches of addressing the harms of illicit drug use behind bars. Additional progress and clinical treatment are also urgently needed to reduce demand.

As I document later in this report, placing a prisoner in an austere cell with no plumbing, in a security gown, with no certainty of release for days on end to carry out a search for suspected contraband is inhumane, degrading and quite likely unlawful. The “war” on drugs behind bars can never be won using extreme measures like indefinite solitary confinement. It seems harmful and unhelpful to punish people for what are ultimately substance abuse and addictions issues. Absolute drug prohibition does not work in the community and it will not work in prison. An overhaul and renewal of CSC’s drug policy is desperately required if more promising and innovative harm reduction measures, like the Overdose Prevention Service at Drumheller Institution, have any hope of seeing the light of day beyond initial pilot implementation.

Even when transformative change comes to corrections, as it did most recently in the decades long legal battle to end the practice of solitary confinement in Canadian prisons, it is often elusive and difficult to sustain progress or momentum over time. The replacement of solitary confinement with a set of legal standards that mandates meaningful human contact behind bars and imposes statutory limits on how long a person can be held in depriving environments or circumstances, is a case in point. Outside of the Structured Intervention Units, all kinds of restrictive forms of confinement (defined as less than four hours out-of-cell time per day) remain a stubborn and substantive reality as my investigation of male standalone maximum-security facilities illustrates. The threshold for out-of-cell time, inclusive of meaningful contact with others, is now established in federal law, yet there remain many forms of confinement and circumstances where even these minimal requirements are not being met or respected.

This year’s report also includes an updated and substantively more involved documentation of the Black prisoner experience in Canada, an area that my Office first reported on in 2013. A decade later, major issues documented in that seminal report – discrimination, racism, labelling, stereotyping – remain relevant concerns that severely impact equality of outcomes for Black persons in federal prisons.

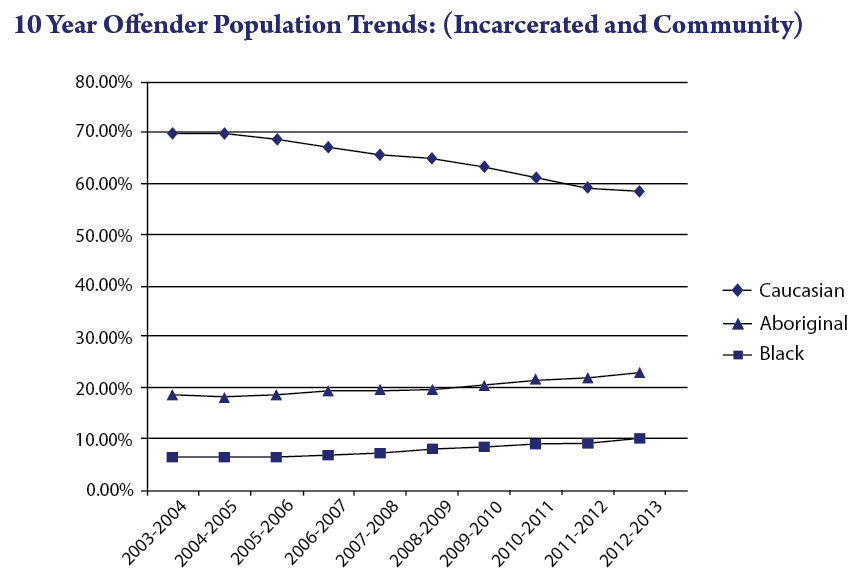

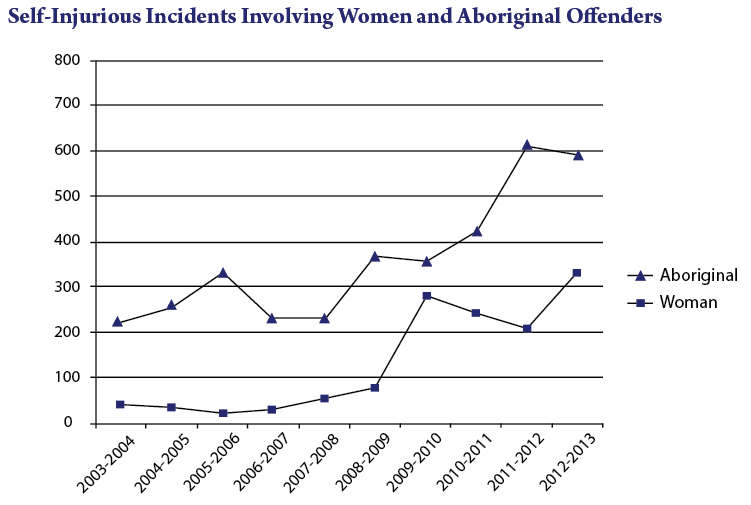

The first of a two-part investigation that updates the Office’s 2013 Special Report to Parliament, Spirit Matters: Aboriginal People and the Corrections and Conditional Release Act , tabled March 2013, is also featured. Few of the findings contained in this introductory, context-setting piece will come as a surprise to anyone familiar with the plight of over-representation or disparate outcomes for Indigenous people in federal custody.

The ability of my Office to effect change must also be understood and evaluated in the context of our, rather, successful ability to address complaints and issues at the site or individual levels in a timely manner. My team of investigators work diligently to establish positive rapport with staff and prisoners alike at the institutions to which they are assigned. Relations between my investigative staff, CSC staff, and management at penitentiaries across Canada are uniformly productive, professional, cordial and responsive. OCI staff work tirelessly, often without much recognition, to resolve issues informally and at the lowest levels possible. Our rate of positive redress and resolution of issues at the site or individual level of complaints is significantly better than the progress we make on systemic issues. Despite travel, prison closures, and visit restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, this past year my team of investigators was still able to conduct more than 60 in-person or virtual visits to federal institutions.

I am immensely proud of the body of work reported here, all the more impressive given that it was completed during another year of COVID-related restrictions which required adapted working conditions.

Ivan Zinger, JD., Ph.D.

Correctional Investigator

June 2022

Executive Director’s Message

Although we were hopeful that the restrictions imposed by the pandemic would be lifted in the last year, our hopes were quickly dashed by COVID-19 variants causing more lockdowns, both inside and outside of federal correctional facilities. The evolving and uncertain situation has continued to cause much hardship not only for the people we serve behind bars, but for our employees as well.

Despite these challenges, the fact that we were still able to spend 83 days in institutions, comprising 46 visits, speaks volumes about the dedication and commitment of our employees. These visits were carried out in all the regions. Some institutions that required our attention were visited more than once: including the maximum-security institutions, notably Atlantic (2x), Edmonton (2x), Donnacona (2x), Port Cartier (2x), Millhaven (2x), and Kent (3x). Some women’s institutions were also visited more than once. The Correctional Investigator alone visited nine institutions, providing his expert assessment and advice on what he observed. I too had the opportunity to conduct introductory visits at eight institutions to see first hand the reality of life behind bars for both incarcerated individuals as well as for the CSC employees who work there. I value the cooperation and collaboration we receive from CSC staff and management. Many important issues are resolved at the institutional level between OCI and CSC employees.

Conducting in-person visits in and through the pandemic demonstrates our continued attention to the needs of the people we serve and our commitment to prison oversight. Our visits ranged from one-day inspections to open visits with full case loads of meeting incarcerated persons, hearing about and acting upon the issues and concerns they raise.

Our policy and research staff, as well as investigators, showed resilience in their efforts by performing multiple visits in a short period of time as restrictions were being lifted. Our early resolution officers have been there to answer thousands of calls and to triage the complaints we received. I want to also highlight the work of our Corporate Services colleagues, who staff and run the back office, and without whom we could not function. Not only do they deal with the increasing government reporting obligations and the disproportionate burden that micro agencies face, but they also helped guide us through COVID-19 restrictions and requirements to ensure the safety of our employees.

This past year has seen the organization move forward with the development of a Three Year Strategic Plan consisting of four key priorities:

- Creating an environment where the OCI is an employer of choice, ensuring a safe and respectful workplace where employees feel empowered and supported;

- Ensuring an organizational structure that is aligned with office priorities, is nimble and agile to respond to emerging issues;

- Improving systemic investigation and inspection capacity and effectiveness through enhanced planning and cooperation; and,

- Implementation of a Data Management strategy that meets the needs of the various functions within the office so as to allow the OCI to more effectively measure and report on the Office’s functions and positive impact.

I am fortunate to work with such a dedicated management team, a passionate and bold Correctional Investigator, and employees who genuinely care about the important mandate of our Office of ensuring safe and humane custody in Canada. Their hard work, passion for social justice, and professionalism continue to impress me. I look forward to begin implementation of our Strategic Plan in the coming year, with a hope that our work and our lives are less impacted by the restrictions of a pandemic, and that things return to normal a bit more.

Monette Maillet

Executive Director & General Counsel

Office of the Correctional Investigator of Canada

National Updates and Significant Cases

This section summarizes policy issues or significant individual cases raised at the institutional and national levels over the course of the reporting period. The issues and cases presented here were either the subject of discussions with institutional wardens, an exchange of correspondence, or an agenda item in bilateral meetings involving the Commissioner, myself, and our respective senior management teams. These areas of unresolved, unaddressed, or updated concern remain under active investigation. Therefore, this section serves to document progress in resolving issues of national significance or concern.

1. Dry Cells

As such, at this time, we do not have an absolute prohibition on placements exceeding 72 hours, as there have been incidents of offenders reinserting or swallowing foreign objects to avoid detection, which necessitates the continued placement beyond a 72-hour period. (CSC, response to 2011-12 Annual Report )

Dry cell placements exceeding 72 hours cannot be explicitly prohibited as it is more than feasible to delay bowel movement beyond 72 hours and, as documented in several medical literature, some individuals do not experience bowel movements more than once (168 hours) or twice (80 to 90 hours) a week. This is why the latest legislative changes do not impose a limit of time but rather imposes medical oversight. (CSC, response to 2019-20 Annual Report )

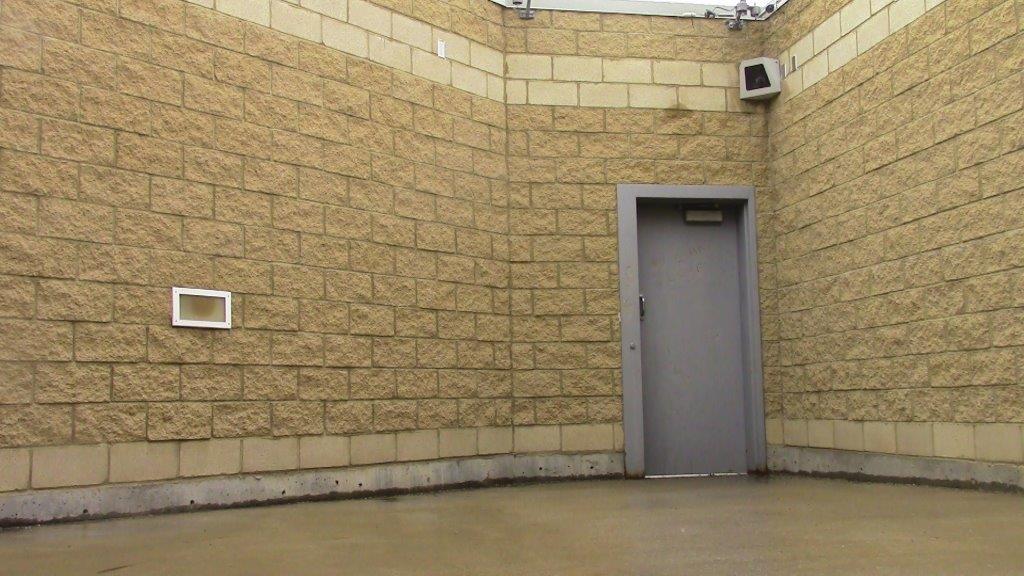

In a recent judicial ruling (November 2021, Adams v. Nova Institution ), the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia deemed the practice of using a dry cell for women suspected of concealing contraband in their vagina unlawful because they could be subjected to longer, or possibly even indefinite periods of dry cell detention. For context, “dry-celling” a prisoner is an extraordinary procedure requiring strip-searching, around the clock monitoring and observation, and 24/7 illumination of the cell. It is carried out under the expectation that the prisoner will eventually “expel” the suspected contraband. In this case, the court found that a former prisoner at Nova Institution for Women had been dry-celled for more than two consecutive weeks after she was suspected of concealing drugs in her vagina. On the 15th day of her dry cell confinement, a pelvic exam finally confirmed that she was not concealing any contraband in her body.

The court initially gave the government six months to review its policy in this area, a deadline that was subsequently extended and expires in July 2022. In response, in April 2022, the federal government gave notice of its intention to amend the Corrections and Conditional Release Act to prohibit the use of dry cells for women suspected of concealing contraband in their vagina.

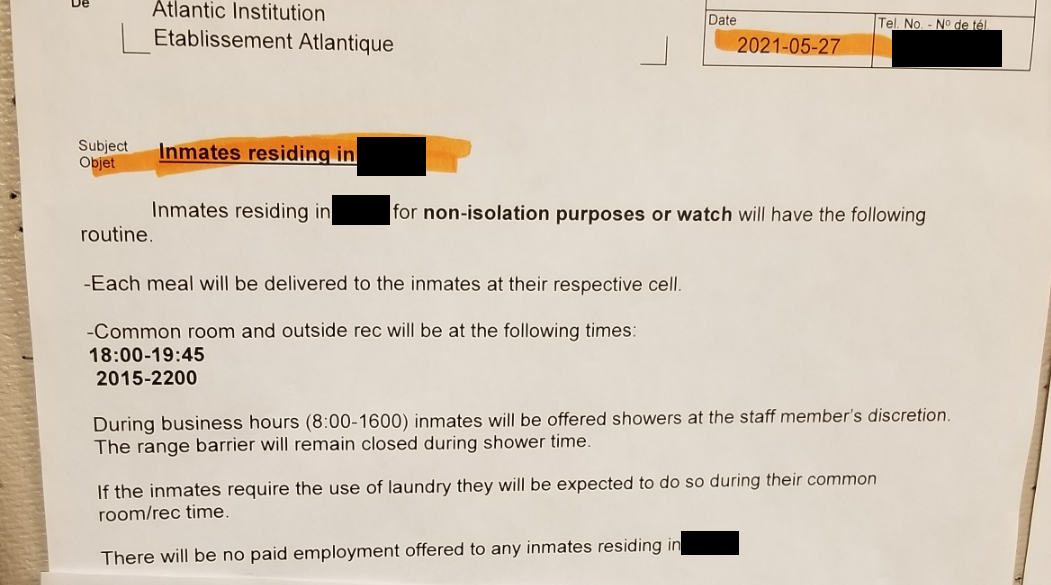

CSC has also taken notice of the ruling, issuing an interim policy bulletin on April 25, 2022. The bulletin states: “Effective immediately, inmates believed to be carrying contraband in their vaginal cavity, or elsewhere other than their digestive tract, will not be placed in a dry cell.” It also directs that CSC’s National Headquarters (NHQ) are notified when a dry cell placement exceeds 72 hours. According to the interim instruction, this new requirement is intended to “enhance oversight” and allow NHQ, “to provide additional guidance where necessary.”

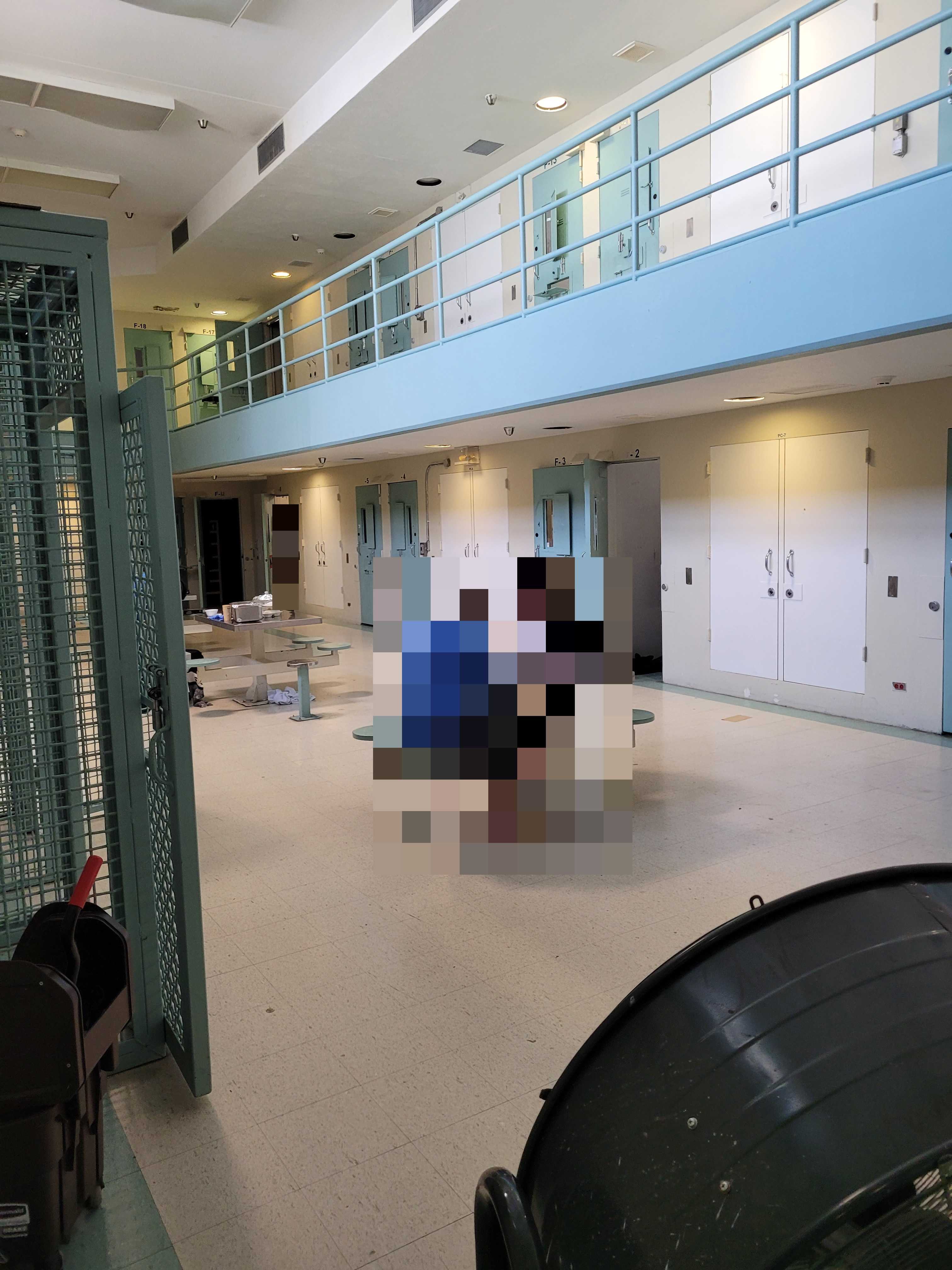

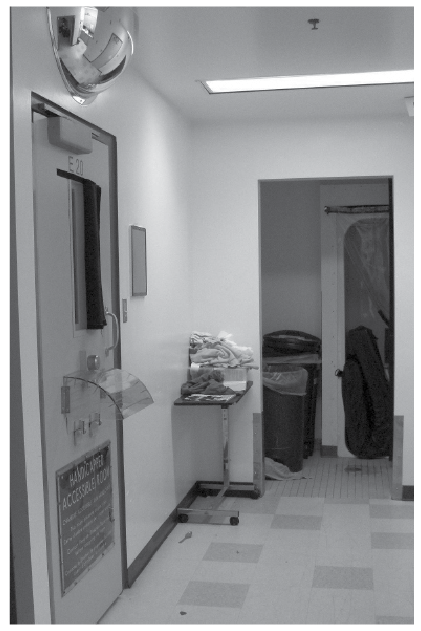

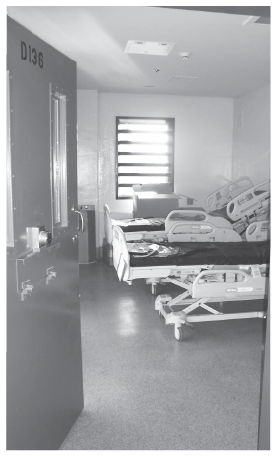

Warkworth Institution – Interior of a dry cell.

Warkworth Institution – Dry cell.

Based on the Government and CSC’s responses thus far, there does not seem to be any intention to go any further and place a wider ban or introduce additional restrictions on the controversial practice of dry-celling, a procedure which I have previously described as being “by far the most degrading, austere and restrictive imaginable in federal corrections.” The point of departure for this case and the ruling itself are based on a rather narrow set of arguments and facts. The Crown attempted to convince the court that the prisoner’s dry cell detention was, in fact, illegal , some kind of “isolated and localized (not systemic) incident of maladministration” on the institution’s part, and that, in any case, the definition of a “body cavity” search in federal corrections does not include concealment of contraband in a vagina. The judgment prohibits the use of dry cell placements for women prisoners suspected of carrying contraband in their vagina. It does not pronounce more widely than that. The more compelling public interest in the case of Adams v. Nova Institution involves whether keeping a prisoner in depriving and degrading conditions, for an indefinite duration, should be considered lawful, particularly in context of the recent abolishment of solitary confinement in Canadian prisons.

The Office first raised a set of concerns around dry cell practice in its 2011-12 Annual Report, a time when there were few safeguards and virtually no internal oversight of this practice. Since then, CSC has implemented various reporting and procedural safeguards – the requirement to give written notice for reasons of placement; an opportunity for incarcerated persons to retain and instruct legal counsel without delay; provision to give notice to and daily visits by Health Services; and, a daily review by the Warden of placements.

Notwithstanding, CSC has resisted placing any upper limit on how long a person can be held in a barren cell with no plumbing under continuous observation. While the circumstances depicted in the court’s judgment are “isolated and localized” (i.e., not systemic in nature), the practice of detaining a prisoner in a dry cell for an undefined period of time is far from unusual. In the reporting period, the Office intervened in the case of a young Indigenous woman who was dry-celled for nine consecutive days. In my opinion, there can be no further reason or justification to hold a person in such depriving conditions. As I have stated previously, I think this practice should be capped at 72 hours. After three days, it is my belief that this procedure is excessive and unreasonable, if not strictly punitive.

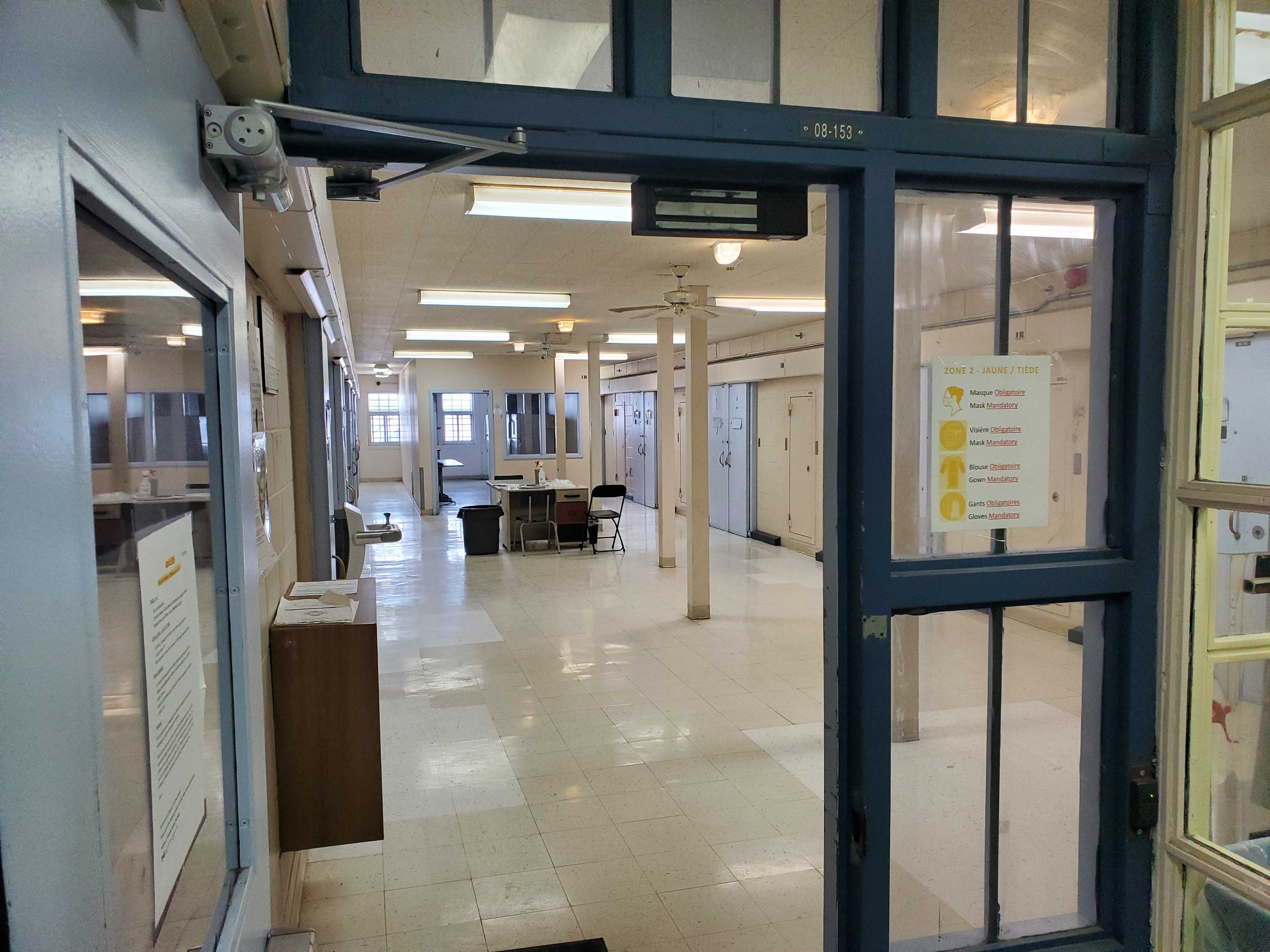

Drummond Institution – Inside a dry cell.

Drummond Institution – Outside the dry cell.

It is not known how often dry cells are used in federal prisons, as there is no obligation for the Service to report publicly on this practice. More than a decade after the Office first reported on this issue, there is still considerable variation in practice between and across regions and even within institutions with respect to the interpretation and procedures for dry-celling. The current record-keeping and reporting mechanisms that are in place (i.e., rationale for placement, record of seizures, observation reports, logbooks detailing periods of stay) are not consistent from one site to another. Incident and observation reports of dry cell placements are buried in individual preventive security files.

More significantly, there are little checks and balances in place to review or challenge the quality or validity of the information used to place or maintain an individual in a dry cell. Placements of this nature require “reasonable and probable grounds,” a legal threshold that cannot be satisfied on the basis of a hunch or individualized suspicion. Aside from voluntarily surrendering the contraband, the only certainty of release from a dry cell is a bowel movement, and only then, if there is some kind of contraband expelled and retrieved. Otherwise, as the Nova Scotia judgment illuminates, placements can extend indefinitely with little practical means to challenge, quash, or end what could potentially constitute cruel and unusual treatment or punishment. It was precisely the indefinite nature of administrative segregation (or solitary confinement), defined as two hours or less out of the cell, that led the present government to abolish that particular correctional practice. Arguably, dry-celling is an even more egregious form of detention, one that is virtually devoid of any kind of external review or oversight.

It is expected that dry cell placements are limited to what is reasonably required and for the shortest possible time. However, given data and record-keeping limitations, it is currently impossible to corroborate the actual number or duration of these placements. Furthermore, the requirement for Health Services to monitor dry cell placements is yet a further violation of its patient advocacy role – another “dual loyalty” problem that inappropriately obliges health services personnel to be involved in discipline and security matters.

Arguably, dry-celling is an even more egregious form of detention, one that is virtually devoid of any kind of external review or oversight.

For all of these reasons, I conclude that the additional internal review and notification measure that the Service has put in place to respond to the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia’s decision (requirement to report to NHQ on dry cell placements exceeding three days) is inadequate and insufficient. This measure does not rise nearly high enough to meet the life, liberty, and dignity concerns and interests at stake.

- I repeat my recommendation to prohibit any indefinite dry cell placement beyond 72 hours.

2. Correctional Service of Canada’s Drug Strategy

This update reviews select aspects of CSC’s drug policy. It assesses progress in addressing concerns and barriers to participation in the Prison Needle Exchange Program (PNEP), first raised in my 2018-19 Annual Report. It also documents the Office’s preliminary observations of a related harm reduction measure – the Overdose Prevention Service (OPS) – at Drumheller Institution, Alberta. It concludes with some comments on CSC’s zero-tolerance drug policy and calls for a more balanced, evidence-based and updated policy statement (Commissioner’s Directive 585 – National Drug Strategy ) to more comprehensively and compassionately address the harms of addictions and drug use among federal prisoners.

Prison Needle Exchange Program

In the Office’s 2018-19 Annual Report, I reported on the challenges and barriers in the initial implementation of CSC’s prison-based needle exchange program. At that time (as of April 2019), the program was just beginning to be implemented in a select number of institutions and there were only a handful of individuals enrolled. I made a number of preliminary findings and recommendations to address the surprisingly low number of participants in the program:

A zero-tolerance approach to prisoner drug use and possession conflicts with PNEP’s harm reduction principles and practice. Footnote 1

Use of a Threat Risk Assessment (TRA) as a precondition for PNEP participation turns potential participants away.

Access to needles/syringes are not determined by need (one-to-one needle/syringe exchange).

Lack of multiple access and distribution points (must return used needles to Health Services).

Lack of participants/patient confidentiality.

Active opposition among front-line staff.

Perceived involvement of the Parole Board of Canada.

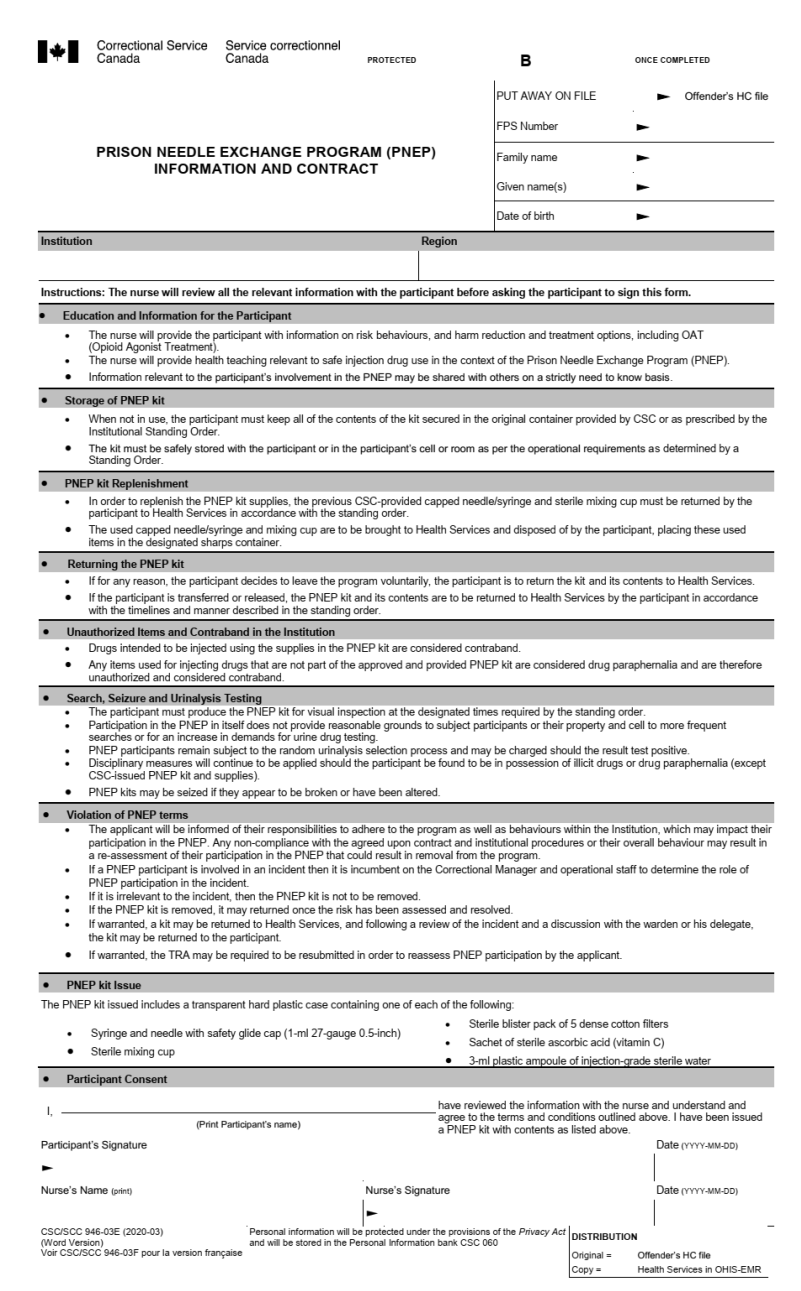

CSC’s Prison Needle Exchange Program (PNEP)

Information and Contract.

Except for the last barrier, all others remain active concerns. Today, the number of prisoners who have expressed an interest or are actually participating in the needle exchange program has not substantially increased, even factoring in the additional sites where PNEP has subsequently been implemented. Currently, a needle exchange service is operating at nine federal penitentiaries, including all five women’s sites. Based on a March 2022 snapshot, there were 46 individuals participating in the program, including seven federally sentenced women. A few sites have yet to attract even their first participant, while a few other institutions where the program had been implemented were shuttered at the onset of COVID. The planned phased national roll-out of the needle exchange program was also temporarily suspended, ostensibly by the pandemic.

An interim evaluation of PNEP conducted by an independent expert made similar findings as the Office. The Interim Evaluation Report, dated October 2020, included these observations and barriers to participation: Footnote 2

56% of institutions with a PNEP had no active participants at the time of the evaluation.

The majority of prisoners and some staff at some sites where PNEP existed did not know about the program.

Inconsistency and ambiguity in PNEP eligibility criteria, kit storage and removal procedures and other restrictions on access across sites.

Lack of adequate planning and preparation for implementation.

The PNEP Information and Program Contract (See image), that participants must agree to and sign, contains numerous behavioural expectations and restrictive criteria that could help further explain the lack of prisoner interest and uptake in the program. To date, the program has failed to generate much interest, trust, or confidence from either prisoners or front-line staff. It remains a program largely in name only.

In terms of potential “evidence-based actionable recommendations for program and policy redevelopment,” the interim evaluation offers several practical suggestions:

Reimagining and refreshing of PNEP promotional materials and a proactive approach to promoting and explaining the program to inmates on admission and to Correctional and Operational staff.

Development of a standardized policy document to ensure consistency in PNEP implementation and procedure across all federal prisons.

Widespread removal and communication of the requirement to share PNEP participation with the Parole Board of Canada.

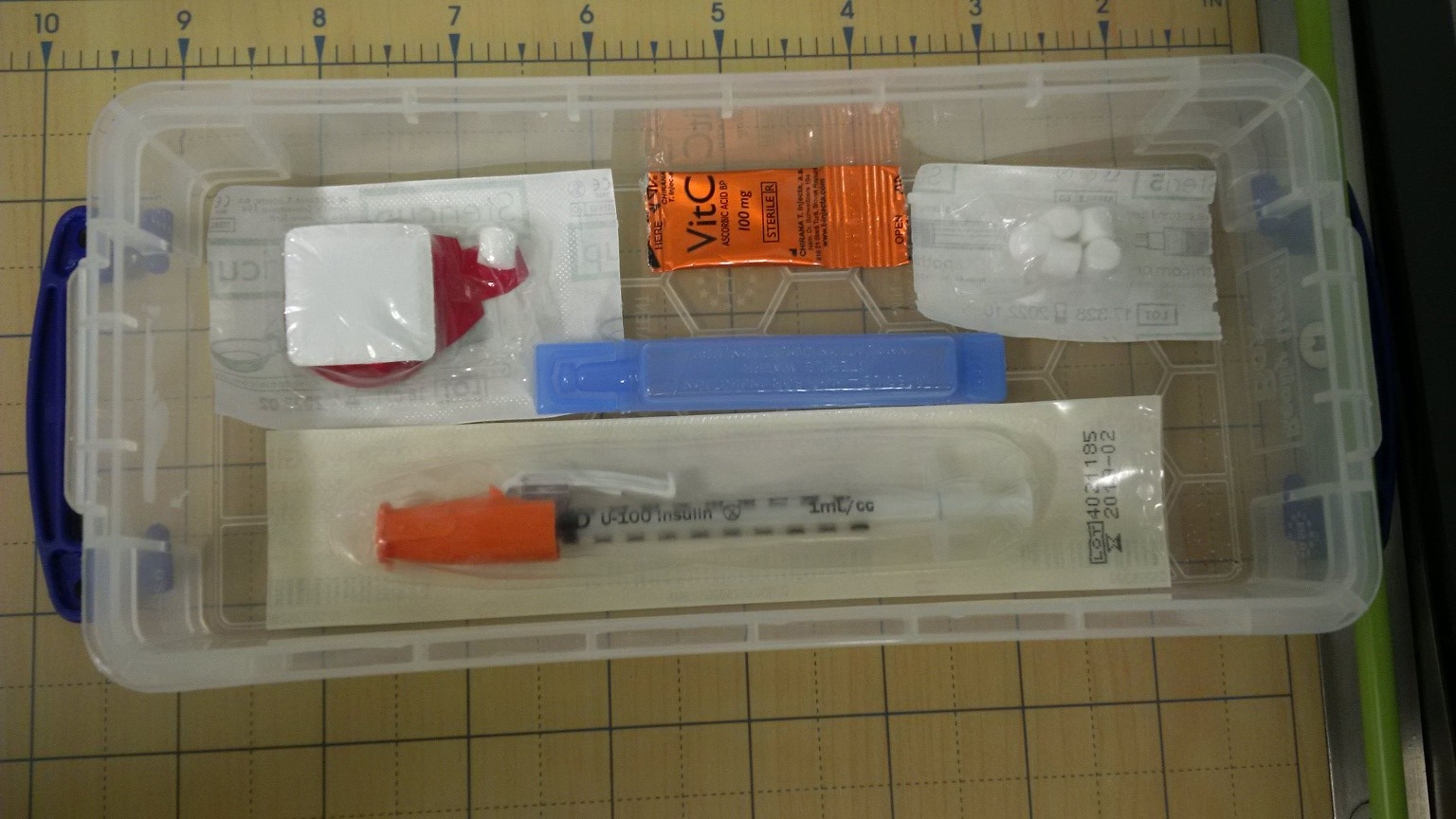

Standard PNEP Kit.

Other related harm-reduction measures endorsed in the midterm PNEP evaluation include:

Increased access to Opioid Agonist Treatment behind bars.

Re-establishment of a Safer Tattooing Program in federal corrections.

Greater availability of Naloxone.

Increased access and distribution of safer snorting equipment.

It is obvious, from the external evaluator’s interim finding and recommendations, that CSC is being asked to embrace a more comprehensive set of harm reduction measures to drug use and addictions in federal corrections, a position which this Office has long endorsed. The problem, of course, is that CSC’s drug suppression practises do not adhere to or respect principles of harm reduction. The question remains: how do we get there amidst resistance and opposition within an organizational culture of zero tolerance? A possible way forward, with learning points that can be implemented, might be found in a related harm reduction program – the Overdose Prevention Service.

Overdose Prevention Service (OPS)

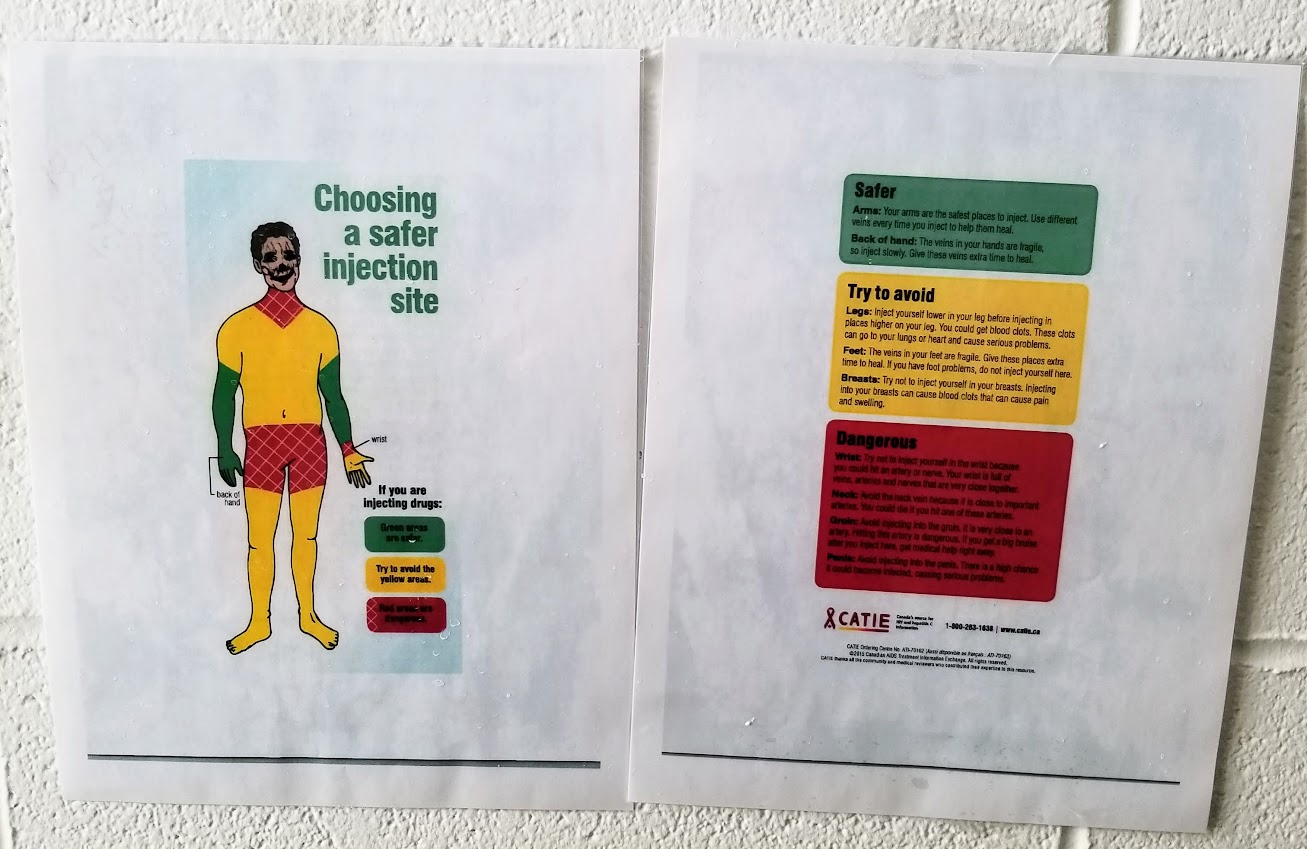

Drumheller Institution – Safe injection site information poster.

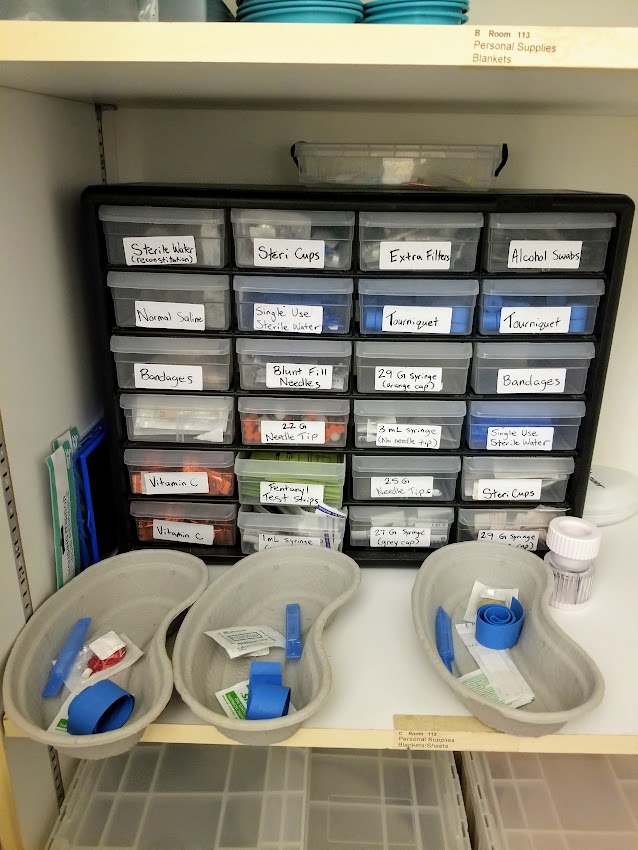

Drumheller Institution – Overdose prevention site.

The OPS, operated by Health Services, which is essentially a safe consumption site in a prison, has been running at Drumheller Institution in Alberta since June 2019. It appears to be the first prison in the world to offer such a service, in which prisoners can access needles, syringes, tourniquets and other sterile equipment and materials to self-administer and consume one dose of their substance per visit. Health care staff monitor prisoners using the OPS for the duration of their consumption and recovery periods. The site is open from 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. All equipment is to be returned to attending health care staff after use.

The established policy and practice goals of the OPS are to:

Prevent non-fatal overdoses and overdose deaths

Facilitate entry into drug treatment services

Reduce multi-use sharing of non-sterile needles

Increase opportunities to provide health promotion

Reduce transmission of blood-borne viral infections

Drumheller Institution – Equipment for safe injections.

CSC health care personnel staffing the OPS received specialized training from the Sheldon Schumer Centre in Calgary (a community-based safe consumption site). They had to learn how to cook and use several different kinds of substances to understand the context of injection drug use and thus assist their “patients.” Participation in the OPS is voluntary (with informed consent), and, unlike the PNEP, a Threat Risk Assessment is not required for participation. The OPS Patient Information and Contract, which spells out expectations and conditions for participation, are not nearly as onerous or security-driven as that for the PNEP. A self-reported history of overdose, illicit drug use, active drug use and an expression of interest to participate in the OPS, are all evidence-based indicators of eligibility to participate in the OPS. Health care staff provide participants with information and guidance relevant to safe consumption practices in the context of OPS.

The service itself creates a safe zone for participants to go from their unit to the injection site. En route to the site, they cannot be charged with contraband by staff if the amount of the drug in question does not exceed personal consumption limits. A prisoner participating in the service is also not subject to additional searching or urinalysis any more than what is allowed for in policy (they cannot be singled out or targeted). Participation in the service does not, however, give carte blanche permission to use drugs or possess drug paraphernalia outside of the OPS.

Drumheller Institution – Equipment for safe injections.

Drumheller Institution – Overdose prevention site.

As explained to one of my investigators who conducted an on-site visit of the OPS in November 2021, Drumheller was chosen to be the site of the first OPS in federal corrections because of its previously high incidence of recorded drug overdoses and prevalence of drug use, estimated to be as high as 70% of all prisoners using. While there was initial pushback from non-health care staff, perceptions and attitudes have since shifted toward a broader acceptance of the program, in part because of a concerted and proactive health care services campaign to raise awareness and acceptance among staff. Front-line staff acknowledged that drug use and drug overdoses were prevalent occurrences before the introduction of the OPS. They routinely had to administer NARCAN and/or CPR on individuals who had overdosed, so the opportunity to reduce the occurrence of these events and interventions with the OPS was welcomed. The OPS also provides a means by which to direct individuals to a safe and supervised place to use, without jeopardizing staff safety. According to information provided to the investigator assigned to Drumheller, frontline staff are now actively promoting the program to prisoners when they find them with or using drugs/paraphernalia.

With regard to uptake and usage, since first opening in July 2019 to March 2022, there had been 1,566 visits to the OPS, involving 52 participants. Since program launch to March 2022, there had been 20 drug overdoses at Drumheller. None of these occurred in the OPS. There were no overdose deaths recorded over that period.

As it stands, the OPS model is not perfect and not without its flaws (e.g., limited resources, limited accessibility and hours of operation, lacks support for peer assistance, availability and distribution of safer snorting equipment). However, it offers a potential best practice in which evidence-based learning and experience can be shared and applied to other federal prisons. It should also be made clear that the OPS is not a substitute or alternative to a redesigned and better implemented needle exchange program or for greater access to evidence-based clinical treatment and addictions programs. Together these two harm reduction measures could work in a complementary manner to more effectively and safely address the harms of drug use and addiction behind bars.

CSC’s Drug Strategy

That there is a need for more access to a wider range of harm reduction measures behind bars now seems beyond doubt or dispute. Between December 2016 – at the outset of the opioid crisis in Canada – and May 2021, CSC increased the number of individuals on Opioid Agonist Therapy (OAT) by 185%. As of March 2022, there were 3,010 persons either on OAT (2,774) or on a waitlist (236), a number which represents close to 25% of the total incarcerated population. The dramatic upsurge in OAT prescribing does not come without its own set of concerns, admittedly requiring much more in-depth analysis and assessment. Minimally, based on OAT uptake numbers alone, it is far from clear that CSC has adequate health care and counselling resources to provide effective and lasting treatment support and intervention.

These questions aside, there are other factors, trends and indicators suggesting that CSC’s current approach to drugs and drug use among prisoners is heavily tilted in favour of drug suppression and ever more sophisticated and costly surveillance and interdiction methods, such as detecting and neutralizing drone drops. The increasing number of contraband seizures in CSC facilities, jumping significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, suggests more active search and seizure but these activities accomplish little to curb demand.

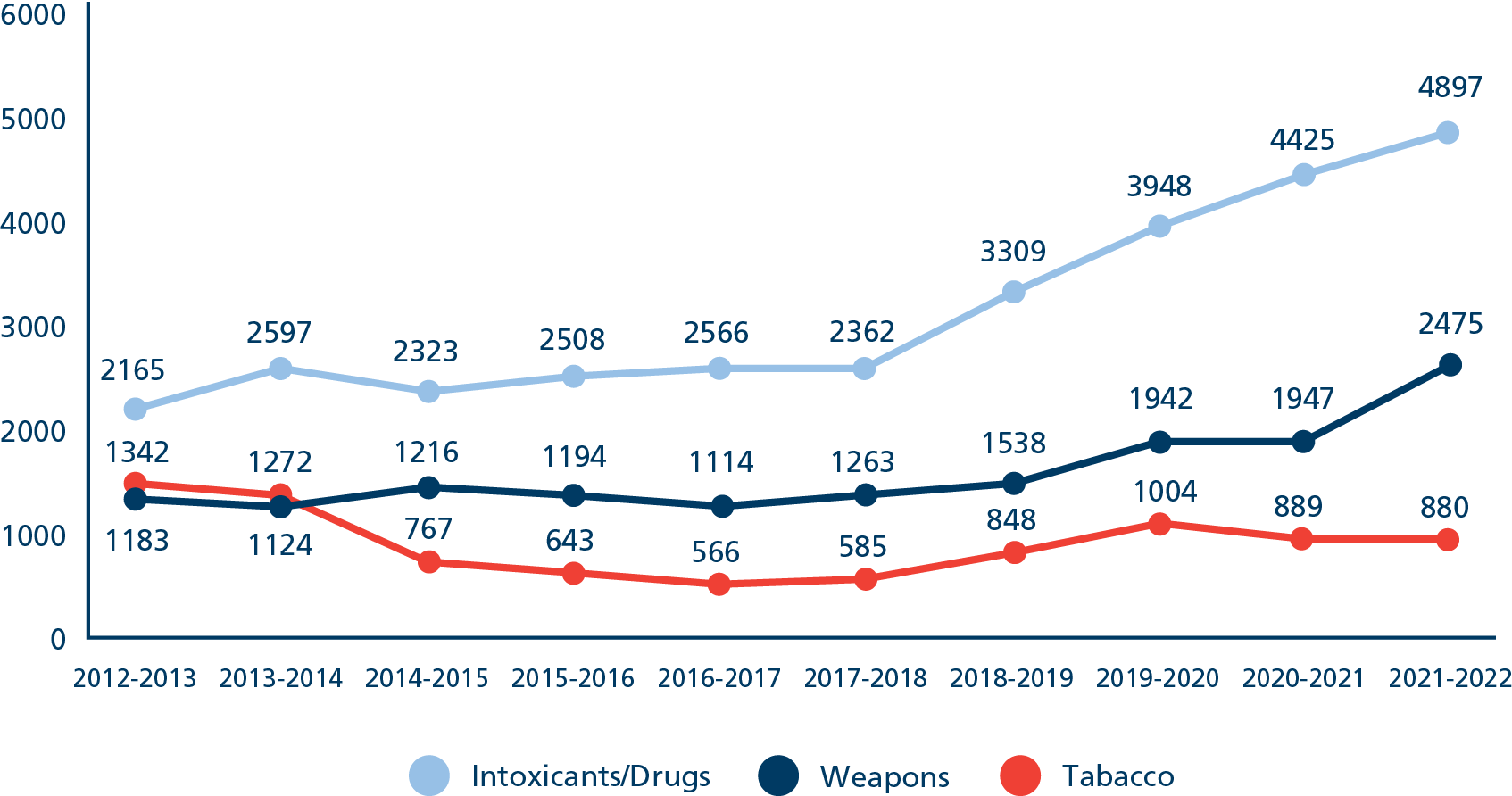

Graph 1. Total Contraband Seized by Type

Similarly, the recent and dramatic upsurge in random urinalysis tests returning positive (indicative perhaps of a COVID-related “bump” in drug use) is another indicator of the insatiable demand for drugs behind bars.

On the policy side, Commissioner’s Directive 585: National Drug Strategy has not been updated since May 2007. It is entirely redundant and irrelevant. There has been little attempt to integrate more recent harm reduction measures, such as PNEP and OPS or expand access to substance abuse programs, within a more balanced and comprehensive drug strategy for federal corrections. The current zero-tolerance approach toward drugs and drug use in CSC facilities leaves little space for other non-interdiction measures based on evidence, treatment, harm reduction, and prevention principles. As a federal entity, CSC is so out of date and non-compliant with the Government of Canada’s stated “comprehensive, collaborative, compassionate and evidence-based approach to drug policy” Footnote 3 that it is difficult to know even where to start in trying to restore a semblance of balance and relevance. What seems certain is that it is both unhelpful and harmful to continue to rely on a series of humiliating and degrading search and seizure measures that target, punish and discipline people for their substance use and addictions, issues that were often contributing factors to their incarceration in the first place.

- With respect to CSC’s drug strategy, I recommend the following set of measures:

The Prison Needle Exchange Program (PNEP) criteria be significantly revamped to encourage participation consistent with actionable recommendations of this Office and the external interim evaluation, with a view to full national implementation within the next 12 months.

The Overdose Prevention Service (OPS) be rolled out nationally, in tandem with PNEP implementation.

Commissioner’s Directive 585 – National Drug Strategy be immediately updated to incorporate evidence-based harm reduction, treatment and prevention principles and practices.

CSC’s zero tolerance policy to drug use and possession is recalibrated to focus on corrective measures for drug diversion and trafficking, rather than stigmatizing, targeting or disciplining persons struggling with addictions or substance abuse disorders.

3. Edmonton Institution

In my 2018-19 Annual Report, I began my case study on the ongoing dysfunction at Edmonton Institution with the following diagnosis: “Edmonton Institution … has been plagued by a toxic and troubled workplace culture where dysfunction, abuse of power, and harassment have festered for years.” By this point, my Office had been reporting on the problems at Edmonton Institution for many years. Both the previous Minister and Commissioners of Corrections had made personal interventions and a series of internal reviews and investigations had been launched. Numerous disciplinary actions had also been taken against institutional staff, and multiple staff surveys had been conducted to assess workplace culture and needs.

In the same report, I also publicized findings from an investigation my Office conducted on a series of prisoner-on-prisoner assaults that occurred at Edmonton Institution between August and October 2018. These findings suggested that frontline staff continued to act with impunity, allowing prisoners to assault other prisoners on repeated occasions with zero consequence. The Commissioner’s response was swift and decisive. Corrective actions were taken, including staff suspensions, the launch of an internal disciplinary investigation, and “renewal” measures to address workplace culture such as appointing a new warden and empowering management to restore a healthy and respectful workplace environment.

In my 2019-20 Annual Report, I provided an update on the disciplinary measures that had been taken in relation to the prisoner assaults. Though six of the ten CSC staff members investigated were subject to minor disciplinary measures, not one of senior rank received a reprimand of any kind.

Virtual and in-person visits conducted through the pandemic indicated a worsening of problems and tensions at this troubled institution, including staff shortages, inadequate out-of-cell time, a general decline in mood and mental health among prisoners, warehousing of medium-security prisoners, and restricted access to private family visits. These issues were raised with the warden in August 2021. Despite a number of measures taken by the institution to address these issues, my Office continued to receive numerous calls, complaints, and inquires related to ongoing and very serious allegations at Edmonton Institution.

In November 2021, my Office conducted an exceptional closed visit to Edmonton Institution, which took place over three days (November 1 to 3, 2021). Two of my senior investigators met with and interviewed prisoners from all sub-units, as well as staff and managers from all departments. They also conducted a series of in-depth interviews with several members of the senior management team, and collected unit logbooks and other documentation.

Preliminary findings were reported to the Commissioner on November 12, 2021, and included the following:

Growing number of subpopulations renders nearly all group movement impossible.

Overpopulation and double-bunking, both unusual for maximum-security prisons.

Warehousing of medium-security prisoners.

For months, regular units have had a maximum of three hours out-of-cell time, daily.

Out-of-cell access is limited to the gym, mini-yards, or common rooms; some units were restricted to 50 minutes of tier time, behind barriers, twice per week.

Access to showers, telephones and laundry facilities limited to 15-minute slots, one person at a time, once or possibly twice a day depending on staffing.

One-year waitlist to access mental health services.

One computer video visitation station to service 258 prisoners.

No programs, no meaningful work opportunities, access to education is restricted to cell studies, and meals are taken alone and in a cell.

My investigators observed conditions of confinement that were oppressive and intolerable by any standard. To be clear, restrictions on services and out-of-cell time at Edmonton Institution go well beyond the effects or impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. As concerning, it appeared that long-standing tensions and conflict among and between different staff groupings and management had resurfaced. There was little respect for management among the front-line ranks. Some staff described the chain of command as “broken.” The number of correctional officers on long-term leave was extremely concerning, indicative of a workplace in crisis. Staffing shortages restrict access to all forms of services and programs, including mental and physical health care. Staff from programs, education and mental health have extremely limited access to the population, and communication with Parole Officers was limited to request forms or mediated through a Duty Officer.

Sticker from Union of Canadian Correctional Officers (UCCO)

In light of these preliminary findings, I suggested national level intervention, including immediate assistance and support from the Commissioner. On December 8, 2021, I received a welcome response from the Commissioner, who shared my concerns and assured me that corrective measures were already underway. These measures included:

The re-implementation of in-person Citizen Advisory Committee meetings. Regular meetings involving various divisions at the institution would review institutional routines and the timely transfer of persons.

Population management meetings would resume, and would receive input from unit reps and other prisoners to promote and plan reintegration strategies.

Establishment of an Inmate Welfare Committee, which would meet regularly with senior management.

A comprehensive on-site review of interventions, including timely access to Parole Officers, access to correctional programs/education outside of the cell and access to cultural interventions.

As of December 8, 2021, the number of double-bunked prisoners was reduced to six from 18, and 13 of the 23 medium-security prisoners had been transferred to medium-security institutions.

Additional video visitation consoles were installed, bringing the total to four.

National headquarters are working with both the institution and the region to address recruitment and staff retention issues.

The back and forth exchanges between my Office, the management of Edmonton Institution and the involvement of National Headquarters are examples of what I would call “oversight in action.” Though the situation at Edmonton Institution is still far from ideal and the systemic problems brought forward are far from resolved, the collaboration and responsiveness of the Commissioner in trying to address Office findings and concerns is encouraging. My Office will continue to closely monitor the situation at Edmonton and intervene as necessary.

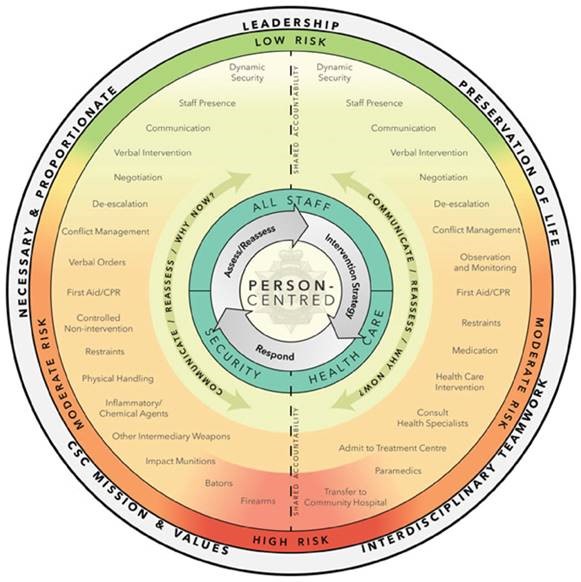

4. Structured Intervention Units

In November 2019, the Corrections and Conditional Release Act was amended to abolish solitary confinement by replacing the previous administrative segregation regime with Structured Intervention Units (SIUs). In my 2020-21 Annual Report, I reported my preliminary observations on SIUs, which were implemented in November 2019. At that time, I made four major observations:

- The lack of data and transparency from CSC with respect to its SIU operations has made it difficult to assess its compliance with legislation.

- The expeditious removal of prisoners from SIUs and compliance with Independent External Decision Makers (IEDMs) removal orders has been challenging.

- Some individuals find SIU conditions more favourable than the mainstream maximum-security prison population because of their greater access to services and interventions, daily visits by nurses and wardens, more opportunities to engage with non-security staff, and the possibility of greater out-of-cell time. Given this situation, some individuals refuse to leave the SIUs, as even the IEDMs have attested.

- The pandemic has generally spared individuals confined in SIUs from the restrictive impact COVID-19 has had on prisons in general, with the exception of lockdowns during institutional outbreaks.

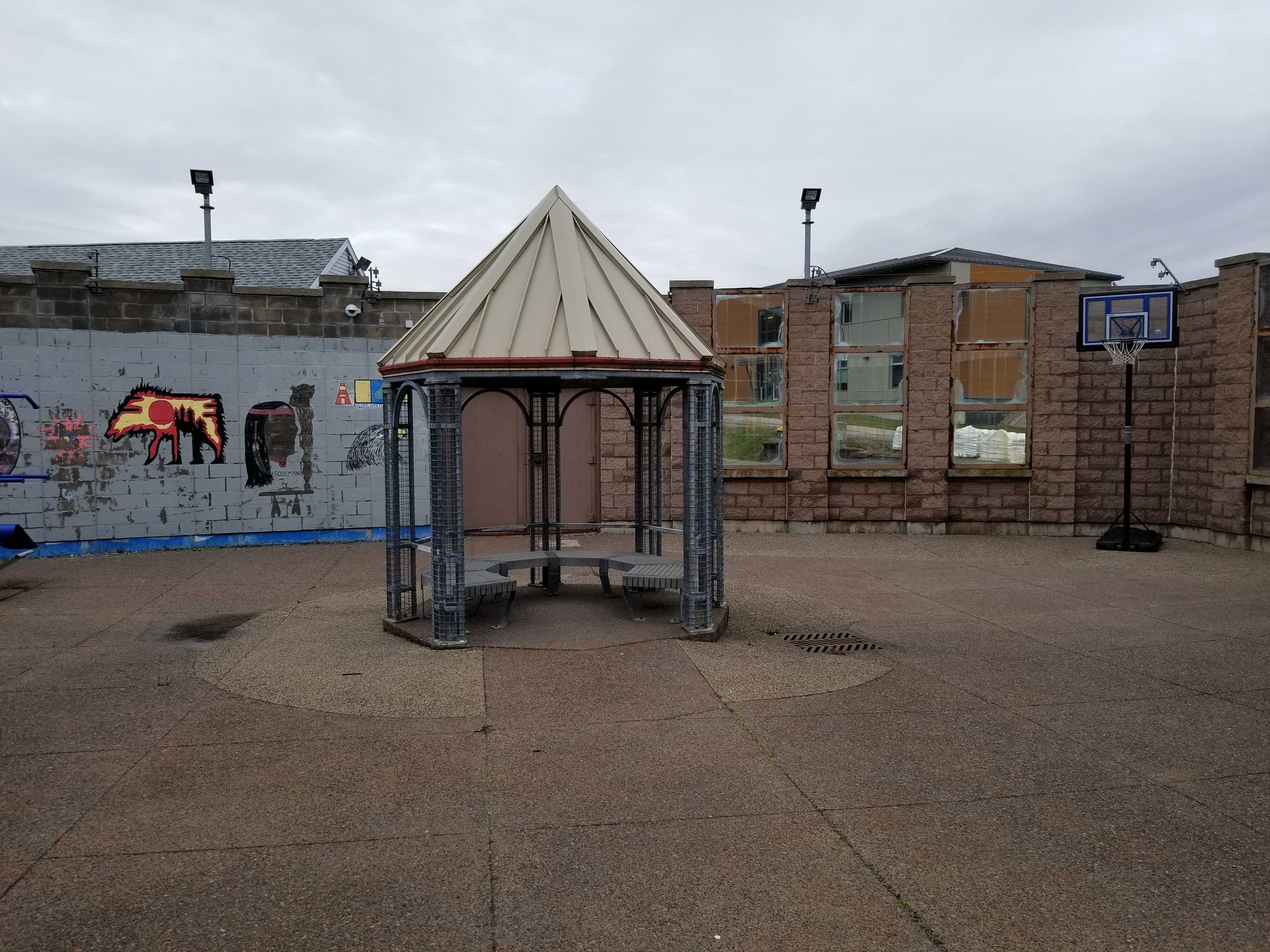

Stony Mountain Institution – SIU exercise equipment in yard.

Stony Mountain Institution – SIU cultural room.

Edmonton Institution for Women – SIU.

Port Cartier Institution – SIU yard.

Based on these findings, I recommended that CSC publicly release a quarterly record of SIU transfer authorizations and that a timeline be issued indicating how it planned to meet its legislated reporting requirements.

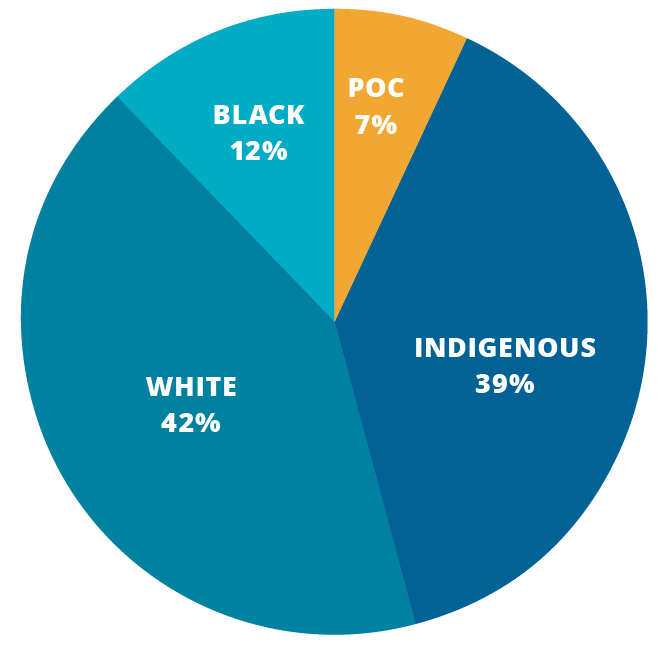

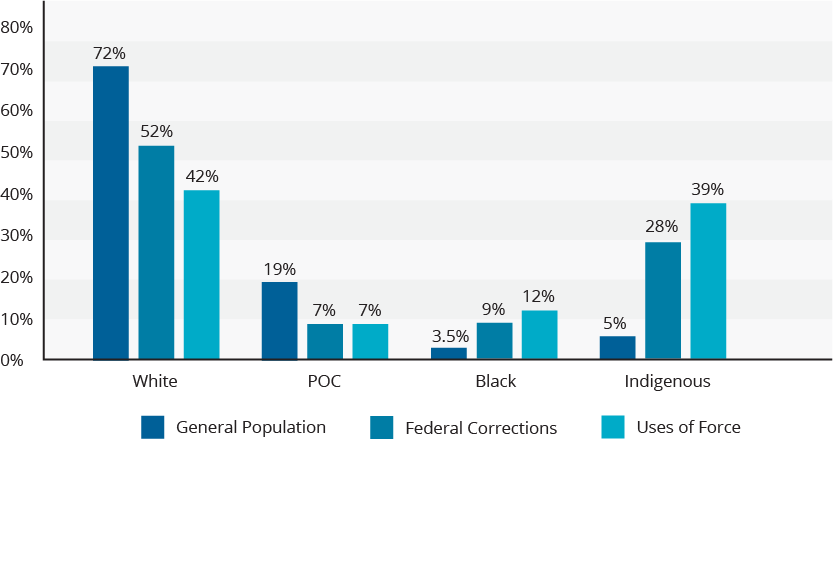

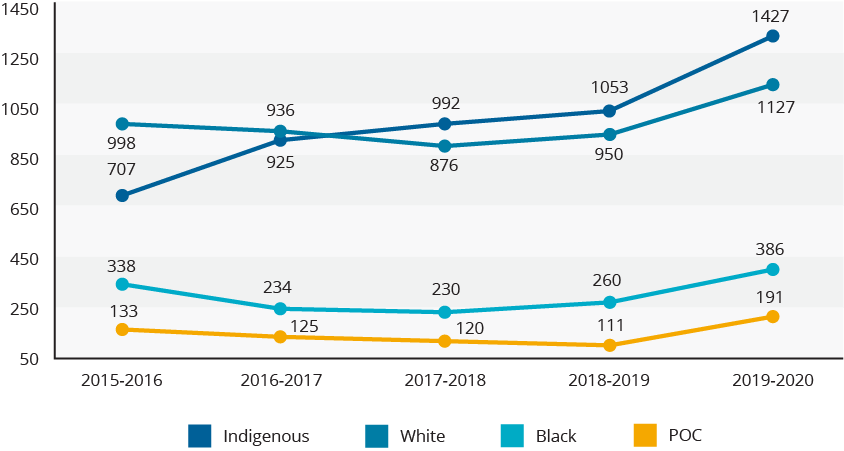

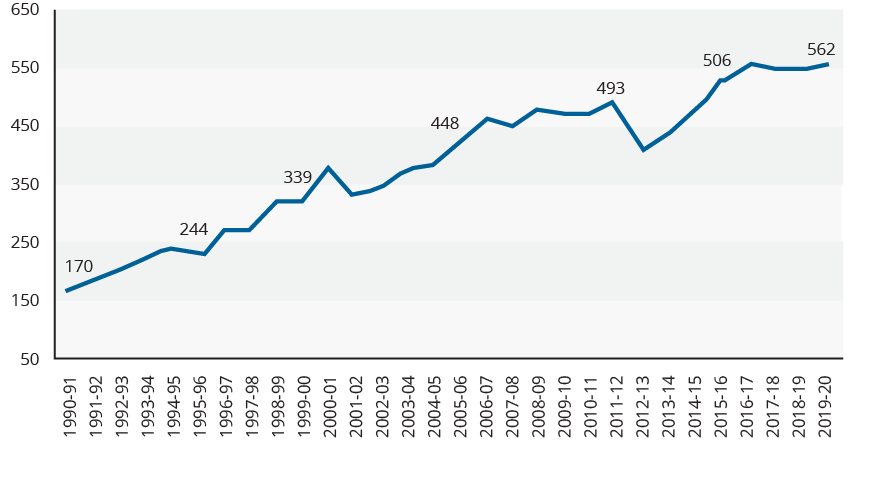

Over the reporting period, I became aware that the Service was maintaining an internal record of SIU indicators. My Office’s analysis of this data highlighted some very concerning findings, particularly with respect to the differential SIU outcomes for Black, Indigenous and Peoples of Colour (BIPOC). My Office found the following with respect to SIUs in 2020-21 Footnote 4 :

Approximately half of SIU stays lasted for 15 days or more, and one third lasted for 30 days or more.

Overall, BIPOC individuals experienced more and longer SIU stays than White persons.

Black people appear to fare worse than other groups on SIU outcomes. For example, they were almost twice as likely as White persons to be placed in an SIU, and were more likely than other groups to experience SIU stays of 60 days or more.

Indigenous individuals were transferred to SIUs at a much higher rate and were more likely to experience SIU stays of 15 days or more, compared to non-Indigenous persons.

The data also suggests that CSC is not fully compliant with its legislated obligations to offer four hours of time out-of-cell and two hours of meaningful human interaction.

In February 2022, I shared my findings and concerns in correspondence to the Commissioner, including the fact that this data was supposed to have been made public. I also highlighted my concerns regarding the general conditions of confinement in maximum-security institutions arising, in part, as a result of the implementation of SIUs. As noted, some prisoners refuse to leave SIUs because they perceive conditions in the SIUs are less restrictive or safer than the mainstream prison population environment. Moreover, I have noticed substantial and dramatic growth in sub-populations in a number of maximum-security institutions, which contributes to more restrictive conditions of confinement, incompatibles, and lower security individuals waiting to cascade. I report on my findings in maximum-security institutions in more detail later in this Annual Report.

In response to my correspondence, the Commissioner commended the work of the Service in maintaining low numbers within the SIUs and indicated that it has been investigating issues highlighted in my Office’s analysis of SIU indicators as well as those in maximum-security environments. Beyond acknowledging my concerns, no concrete steps or initiatives were identified that would indicate how these issues will be addressed.

I have also shared my findings on SIUs with Mr. Howard Sapers, who was appointed in April 2021 by the Minister of Public Safety as the Chair of a renewed SIU Implementation Advisory Panel (SIU IAP). The SIU IAP was established to monitor, assess and report on issues related to the ongoing implementation of SIUs. I have full confidence that Mr. Sapers and the SIU IAP will hold CSC to account with respect to the continued implementation of SIUs and the disproportionate outcomes for BIPOC individuals.

Port Cartier Institution – SIU common area.

Bowden Institution – The SIU range.

5. Over-representation of Indigenous Women in Secure Units (Maximum Security)

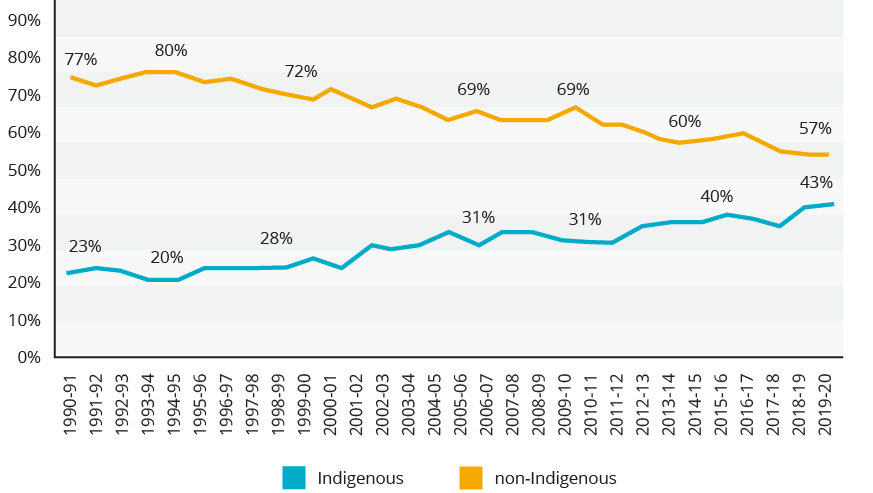

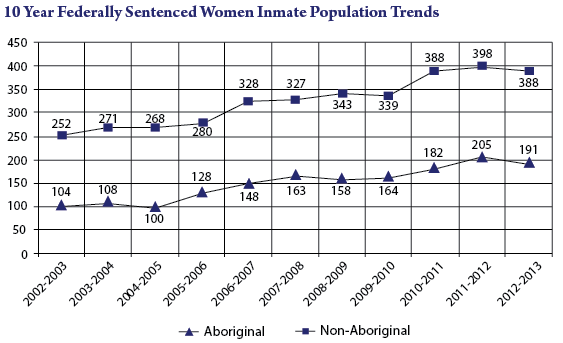

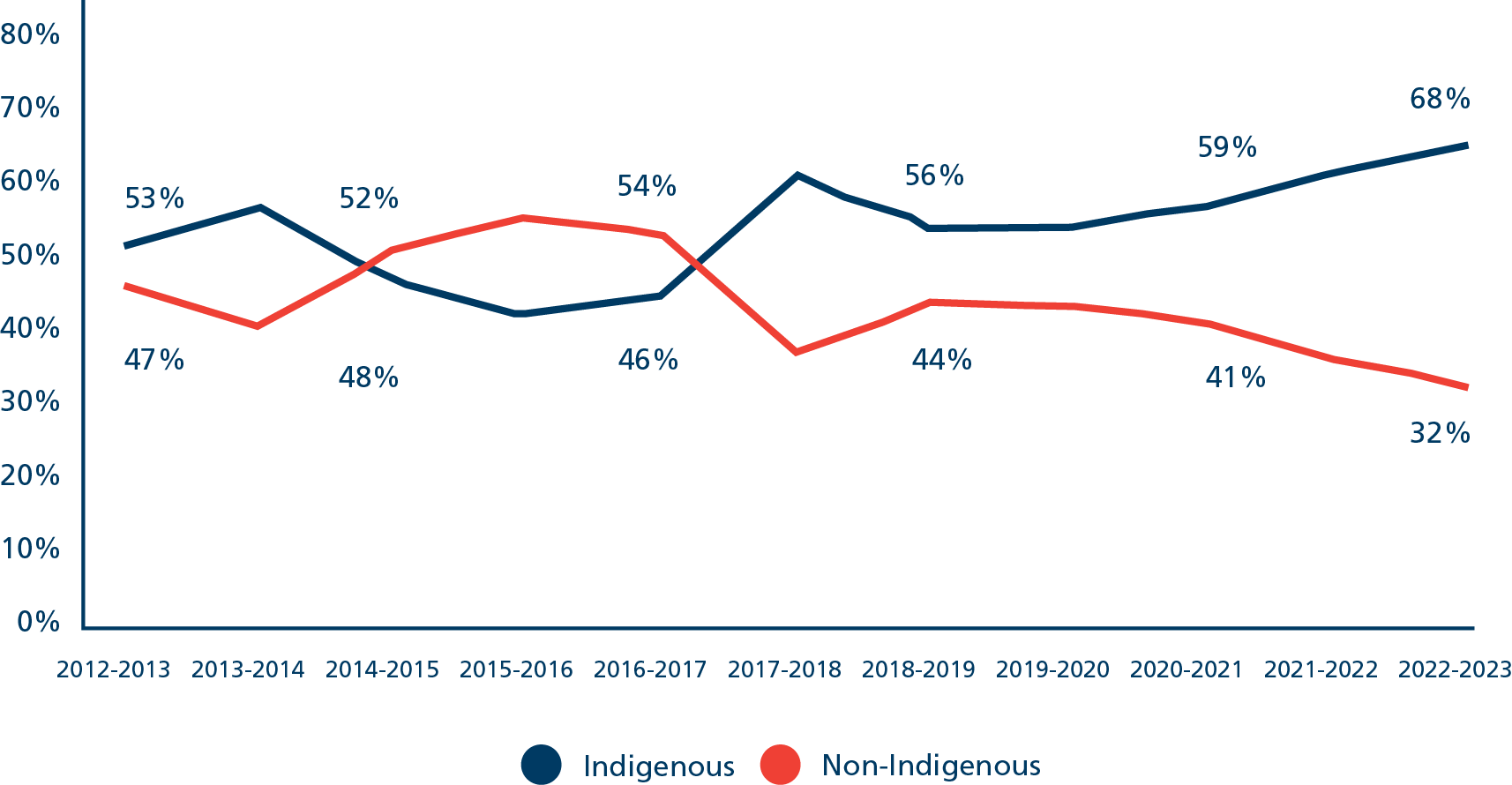

Indigenous women continue to be one of the fastest growing federally incarcerated populations in Canada. In December 2021, my Office issued a press release with data showing that the proportion of incarcerated Indigenous women continued to increase unabated, and was nearing 50% of all federally sentenced women. On April 28, 2022, the number of incarcerated Indigenous women reached 50% for the first time (298 Indigenous and 298 non-Indigenous women in federal custody). Even more concerning is the fact that,of the women who are classified as maximum security, almost 65% of them are Indigenous. Unfortunately, these are not new developments in federal corrections. My Office and others have been reporting on the Indigenization of Canadian corrections for years. A deeper dive into the situation uncovers that this over-representation is largely the result of systemic bias and racism, including discriminatory risk assessment tools, ineffective case management, and bureaucratic delay and inertia.

What do we know about Indigenous women in the Secure Units today?

A review of CSC data extracted on April 9, 2022, reveals the following: 29 out of 45 (64.4%) women classified as maximum security are Indigenous.

25 out of the 29 (86.2%) Indigenous women are assessed as high risk and high need.

20 out of 29 (69%) Indigenous women were born after 1990, reflecting a younger population.

The highest rate of over-representation of Indigenous women is in the Prairie region.

Of the Indigenous women classified as maximum security:

8 women are serving indeterminate sentences, with sentence start dates ranging from 1990 to 2021;

14 women are serving sentences less than four years;

Three women are serving sentences between four and six years;

Three women are serving sentences between 6 and 10 years; and,

1 woman is serving a determinate sentence more than 10 years.

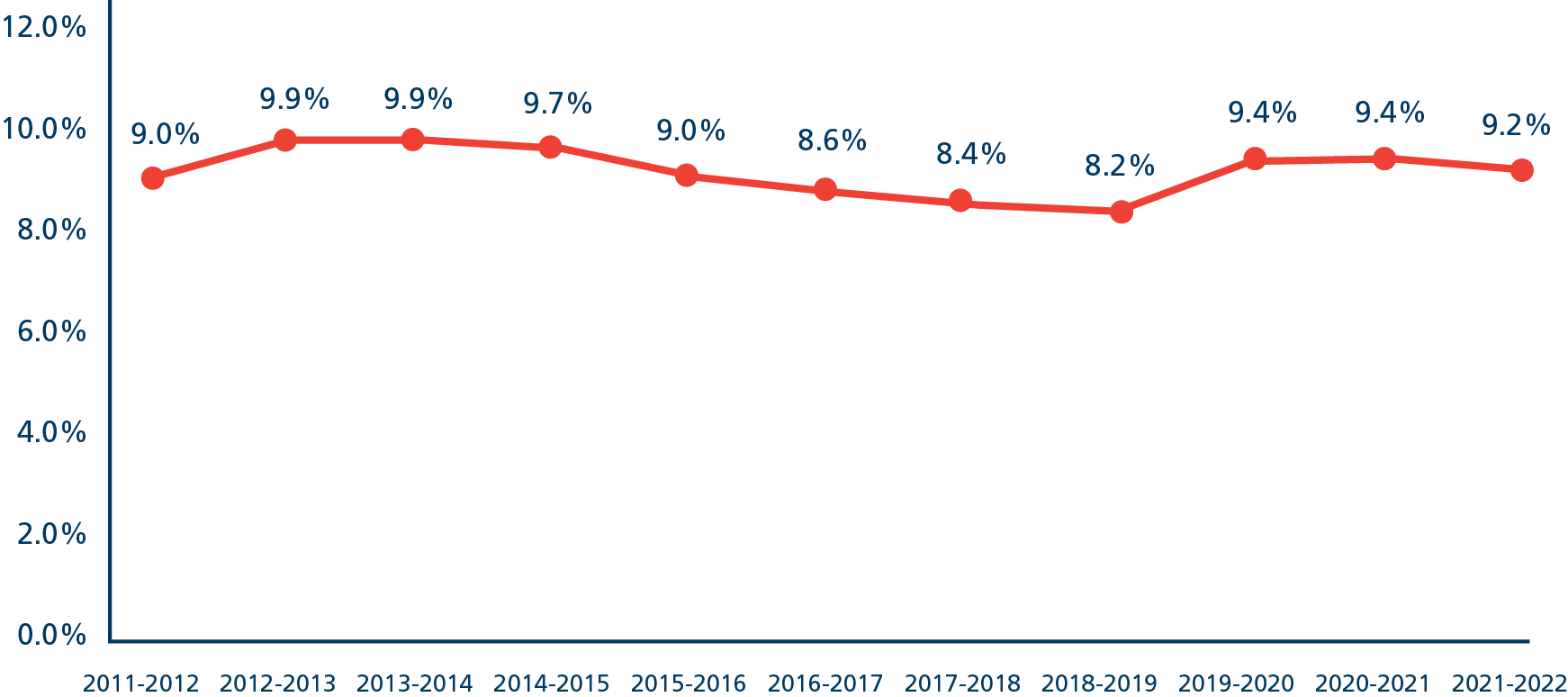

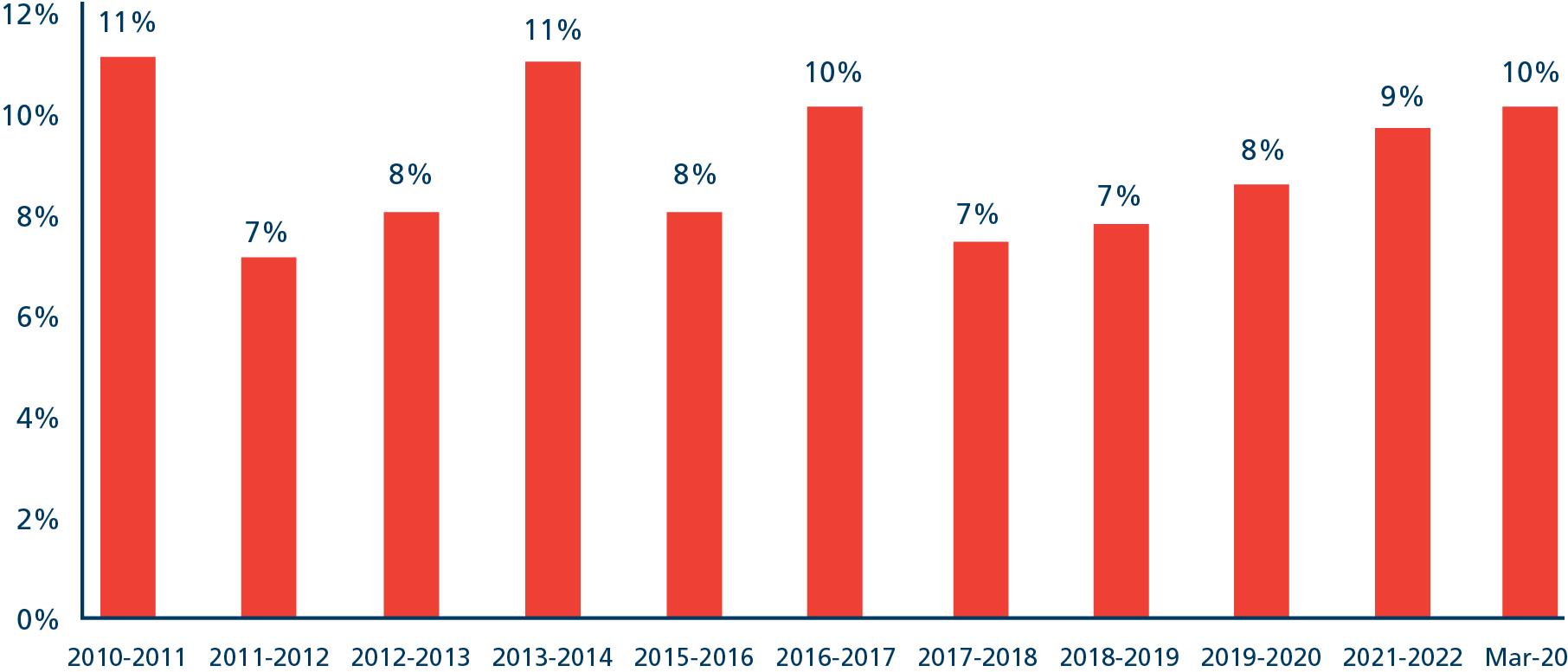

Graph 2. Proportion of Women in Maximum Security

from 2012 to 2022 Indigenous vs. Non-Indigenous

Custody Rating Scale and Security Classification Process

From the very beginning of the custodial intake process, Indigenous women are disadvantaged. The security classification tool used by CSC for all federally sentenced persons is the Custody Rating Scale (CRS). This is a static actuarial instrument designed for, and tested on a predominantly white male population. For years, serious flaws with this primary assessment tool have been raised to the Service – particularly for its inappropriate application to women and visible minorities. The following are a handful of the critiques:

2001: A study funded by Status of Women Canada recommended that CSC, “Examine and design a gender and ethno-culturally sensitive method of assessment and classification.” Footnote 5

2006: The Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice published a study providing evidence that the Custody Rating Scale introduces a systematic bias against Indigenous (relative to non-Indigenous) prisoners, whereby a substantial proportion of Indigenous women are unjustly over-classified to higher levels of security. Footnote 6

2012: Public Safety Canada released a report indicating that the scale fails to take into account any cultural or gender-specific issues, resulting in a double disadvantage based on race and gender for Indigenous women. Footnote 7

2017: The Office of the Auditor General of Canada recommended that Correctional Service Canada examine ways to improve the initial security classification process to appropriately consider the risk factors for incarcerated women. Footnote 8

My Office has repeatedly raised concerns about the use of the CRS for women, and especially for Indigenous women. In 2009, the over-representation of Indigenous prisoners in higher security levels was examined in a report released by my Office, titled, Good Intentions, Disappointing Results: A Progress Report on Federal Aboriginal Corrections. At that point, concerns with the CRS had already been flagged for over a decade. Twenty-five years later the CRS remains in use. I can’t help but ask: Why?

CSC has historically defended the CRS, indicating that it is not the only tool used in the security classification process. Accordingly, as per Commissioner’s Directive 705-7: Security Classification and Penitentiary Placement , the areas of Institutional Adjustment, Escape Risk, and Public Safety are also assessed. Part of this assessment includes an evaluation of employment, education, marital/family adjustment, interpersonal relationships, alcohol and drug use, and living arrangements – areas where Indigenous women are more likely to score higher. Additionally, as in all decision-making for Indigenous prisoners, Indigenous Social History is to be considered. The issue is whether CSC adequately and appropriately considers these areas when making classification decisions. Instead of using this information for the sole purpose of informing programming, treatment and intervention requirements, it seems to be used against these women as indicators of risk.

Indigenous Social History

The decision-making process for all Indigenous prisoners requires consideration of Indigenous Social History (ISH). The ISH examines the direct and indirect social and historical factors that have impacted the individual and contributed to their involvement in the criminal justice system. The assessment is intended to ensure that the unique circumstances of Indigenous prisoners are deliberated, and that culturally appropriate/restorative options are considered and provided. In theory, this should be a very comprehensive exercise to examine and analyze collective and individual circumstances. In practice, however, the ISH typically only consists of a list of factors that have impacted the individual. It is rare to see an analysis of what this means in terms of case management or mitigation strategies, and it is rare to see alternative or restorative options presented as part of the ISH evaluation.

Quotes from ISH Assessments

Although CSC does offer some training and an Indigenous Social History Tool to provide guidance to case management officers, throughout this review and through informal conversations over the years, staff have reported to my Investigators that the training is not enough to properly understand and connect an individual’s ISH to their risk and case management plan.

“I do the best that I can, but more training is needed.”

– Quote from an Institutional Parole Officer.

Without adequately taking into account all of the contributing factors which lead to an Indigenous woman’s involvement in the criminal justice system, the CRS and assessment process fail to appreciate the correlation between an Indigenous woman’s life circumstances, from both a collective and individual perspective. The result is a discriminatory practice. Footnote 9

CSC has advised my Office that they have funded and entered a contract with the University of Regina to review the security classification process as a whole. This is a “ground-up” process that is being led by an Indigenous team.

- I recommend that CSC prioritize the current review of the security classification process, particularly as it applies to Indigenous women. In the interim, I recommend that Indigenous Social History (ISH) be assessed in a meaningful way for each decision rendered and that case management staff are provided with adequate training and support to apply the ISH.

Indigenous Women in the Secure Unit

The Secure Units, as their name suggests, are distinct areas at each regional site with high static and dynamic security and limited movement. The units were introduced to women’s corrections in 1999, with the introduction of the Intensive Intervention Strategy in Women’s Institutions , and are intended to house maximum-security women with high risk or high needs, who require an enhanced level of staffing, support, counselling or other aspects of dynamic security. As reported in the past by my Office, Secure Units are environments where women are subjected to modified routines, restrictive movement, population management challenges, the absence of physical space, heightened population tensions, incidents, mental health crises, and isolation. The environment, infrastructure and lack of resources often make it challenging for women to cascade to lower security levels in a timely manner. Moreover, these units are the most costly to operate.

Nova Institution – SIU and secure unit yard.

Today, the Secure Units are a far stretch from the progressive model originally proposed in the Creating Choices philosophy.

[The Creating Choices Task Force] “was told by federally sentenced women that they needed support, not security. Many others consulted also believe that the traditional security system has little relevance for women whose value systems are rooted more in relationships than in systems. (…) The punitive model is, therefore, particularly irrelevant and harsh in its effect on [Indigenous] women.” Footnote 10

The five principles integral to the woman-centred approach to corrections – empowerment, meaningful and responsible choices, respect and dignity, supportive environment, and shared responsibility – are effectively non-existent in the Secure Units. Moreover, they house a predominantly Indigenous population.

While many Indigenous women with higher risk and needs may benefit from a more structured environment, the restrictive, security-driven approach within the Secure Unit often exacerbates mental health issues, impedes meaningful participation in interventions, and further alienates Indigenous women from their culture.

“I don’t want to die down here.”

– Quote from an Indigenous woman in the Secure Unit.

In the Secure Units, maximum-security women are also subject to a unique classification, or level, system. Consequently, this system results in movement restrictions that disproportionately affect Indigenous women, given their over-representation in maximum security. My Office has reported significant concerns about this level system in the past. In my 2016-2017 Annual Report, I recommended that the level system in women’s corrections be rescinded, as it is arbitrary and exists outside of the law. The movement levels were replaced by the Reintegration Movement Plan in 2019, with the promulgation of the revised Commissioner’s Directive 578, Intensive Intervention Strategy in Women’s Institutions . Although revisions included changes to review and recording timeframes, as well as to the criteria for the plan, staff supervision requirements, and decision-making authorities, the reality is that the level system remains in operation.

Women have reported to my Office that “losing their level” (i.e., being further restricted from movement off the Secure Unit) has devastating impacts. For Indigenous women, this can mean that they losing access to ceremonies (e.g., sweats) or cultural events (e.g., drumming) in the main compound that are not available in the Secure Unit. These women report that when they need these supports the most, they are not permitted to participate in them. As a result, they feel that access to their culture is something that has to be earned.

- Once again, I recommend that the level system for maximum-security women be immediately rescinded.

Grand Valley Institution – Maximum security unit common area.

Photo of the common area at Grand Valley Institution’s maximum security unit.

Access to culture is a right, not a privilege. The Secure Units are not equipped or resourced to provide the cultural support and resources that Indigenous women need. For example, not all Secure Units have dedicated sacred grounds, a dedicated Elder, a complement of Indigenous staff, or a pre-Pathways program. Interventions and services are significantly more limited for a population of women who are assessed as high need. One Indigenous woman explained to my staff that she could not do beadwork without the accompaniment of a staff member, as the small needle that is used is deemed to be a security risk. Beading is a traditional and therapeutic hobby for many Indigenous people and the reliance on over-secure practices that hinder this activity is a clear departure from the Creating Choices philosophy.

Grand Valley Institution – Maximum security unit grounds.

Investigations and inspections conducted by my Office have revealed that many Secure Units do not have a dedicated roster of Primary Workers who are a consistent presence on the unit. Moreover, the proportion of Indigenous staff does not come close to matching the proportion of Indigenous prisoners. Although some Indigenous women reported to my Office that non-Indigenous staff can be understanding and respectful, others reported that working with staff who have a shared history and culture is much more beneficial and allows them to connect better.

Many women describe the feeling of being in the Secure Unit as comparable to being removed from their home communities. A placement in the Secure Unit is, in and of itself, another form of dislocation and displacement. Those women who experienced the Residential School System, or who have a family member who attended, report being especially triggered in the Secure Units. Some women talked about how the criminal justice system and how prisons perpetuate colonization, resulting in many of the same consequences. Modern forms of colonization and its effects remain pervasive and insidious. For incarcerated Indigenous women, this can mean being uprooted from one’s community and sent to a federal institution far from home, or it can mean being isolated in a unit that does not meet their needs.

- I reiterate my recommendation for alternative accommodations for women housed in Secure Units and their eventual closure. Funding and resources currently dedicated to Secure Unit operation should be redirected to better support and address the unique needs of women, particularly Indigenous women.

Best Practices

Throughout the course of this study, Fraser Valley Institution was able to significantly reduce the number of Indigenous women – and women overall – in their Secure Unit. Some best practices to achieve this include:

A rigorous review of all cases on a biweekly basis;

A consideration of what mitigation strategies could be implemented in medium security (e.g., placement in the Structured Living Environment or the Enhanced Support House, additional supports);

Involvement of the offender in the transition plan;

Continuity of care;

Exhausting all options before placement in the Secure Unit;

Combined involvement of the Security Intelligence Office and the Elder to manage gang tensions; and,

A dedicated Elder for the Secure Unit.

6. Mother-Child Program

Mother-child separation by maternal imprisonment can have devastating effects on individuals and families that reach well beyond the length of a prison sentence. Many of the developmental, emotional, and practical disruptions to children, as well as the traumatic consequences of mothers being separated from their children by the experience of incarceration, have been well documented. Footnote 11 In an effort to address this issue, in 2001, federal corrections implemented its first formal policy on the Institutional Mother-Child Program in all women’s facilities, largely in response to recommendations issued by the Task Force on Federally Sentenced Women in their 1990 report, titled, Creating Choices . Footnote 12

The Mother-Child Program, as described in Commissioner’s Directive 768: Institutional Mother-Child Program , is “a continuum of services and supports which aims to foster positive relationships between mothers incarcerated in women offender institutions and units and their child and to provide a supportive environment that promotes stability and continuity for the mother-child relationship.” In essence, the program allows some incarcerated mothers to apply to have their children reside with them, either full-time or part-time through the residential component (children living with their mothers in custody); otherwise, any mother can seek to participate in the non-residential components (includes services such as video visits, private family visits, and/or the recording of stories). Incarcerated mothers are not automatically offered to apply to participate in the program and the availability of space for participation is dependent on “institutional capacity”; therefore, not all mothers are eligible and not all eligible mothers have the opportunity to participate.

Library of Parliament Report on Mother-Child Program

In January 2022, the Library of Parliament produced a report on CSC’s institutional Mother-Child Program. Footnote 13 The report describes the evolution of the program since its inception, provides an overview of the available data on participation rates, and summarizes the existing research (mostly from the US) on the impacts of maternal incarceration on children. The main findings from the report, with respect to the federal Mother-Child Program, are as follows:

Insufficient data/tracking: The program has been “understudied and under-documented.” No formal evaluation has been conducted, there is little concrete data available on program participation and participants, and basic descriptive information of children who participated in the program each year is unknown (e.g., total number, age, length of stay).

Low participation rates: Participation rates have been low since the inception of the program and fluctuations in participation rates have corresponded with changes to the program eligibility criteria in 2008 and 2016.

Restrictive criteria: Restrictive program eligibility criteria contribute to low participation rates overall, and for Indigenous women in particular.

Inconsistent practices: Approvals and participation rates vary considerably by institution.

Unknown impacts on children: There is currently no research examining the experiences of or impacts on, children of whom participated in the Mother-Child Program in Canada.

I would like to further highlight a few of the areas of concern identified in the Library of Parliament report that this Office has also previously raised.

Restrictive Eligibility Criteria and Low Participation

A total of 154 mothers have participated in the Mother-Child Program over the twenty years the program has existed (see Table 1), with a median annual participation rate of five mothers per year. Unfortunately, CSC does not track the overall number of incarcerated women who are mothers, making it difficult to determine who may be in need or qualify for such a program; however, based on some estimates, approximately 66% of federally incarcerated women are mothers. Footnote 14 In the context of the number of women in federal custody today, this would represent nearly 400 incarcerated mothers. Footnote 15 With five mothers participating in the program each year, it does not appear that this program is serving the needs of a significant portion of incarcerated mothers.

Understandably, in an effort to protect and promote the best interest of the child, the eligibility criteria for the program has been stringent; however, changes brought about in June 2008 served to significantly restrict who would be eligible. Footnote 16 These changes included:

Excluding individuals from the program who have been convicted of serious crimes involving violence toward children or those of a sexual nature;

Restricting the part-time program to children aged six and under;

Requiring the support of local Child and Family Services before the participation of an offender is approved; and,

Re-evaluating the participation in the program of any offender who refuses to allow her child to be searched for drugs or other contraband before entering an institution.

Table 1. Final Decisions on Mother-Child Program Applications by Fiscal Year Footnote 17

| FINAL DECISION | 02-03 | 03-04 | 04-05 | 05-06 | 06-07 | 07-08 | 08-09 | 09-10 | 10-11 | 11-12 | 12-13 | 13-14 | 14-15 | 15-16 | 16-17 | 17-18 | 18-19 | 19-20 | 20-21 | 21-22 | TOTAL |

| APPROVED | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 14 | 24 | 13 | 18 | 20 | 13 | 7 | 154 |

| NOT APPROVED | – | – | 1 | – | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | – | 1 | – | – | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | – | 7 | 3 | 29 |

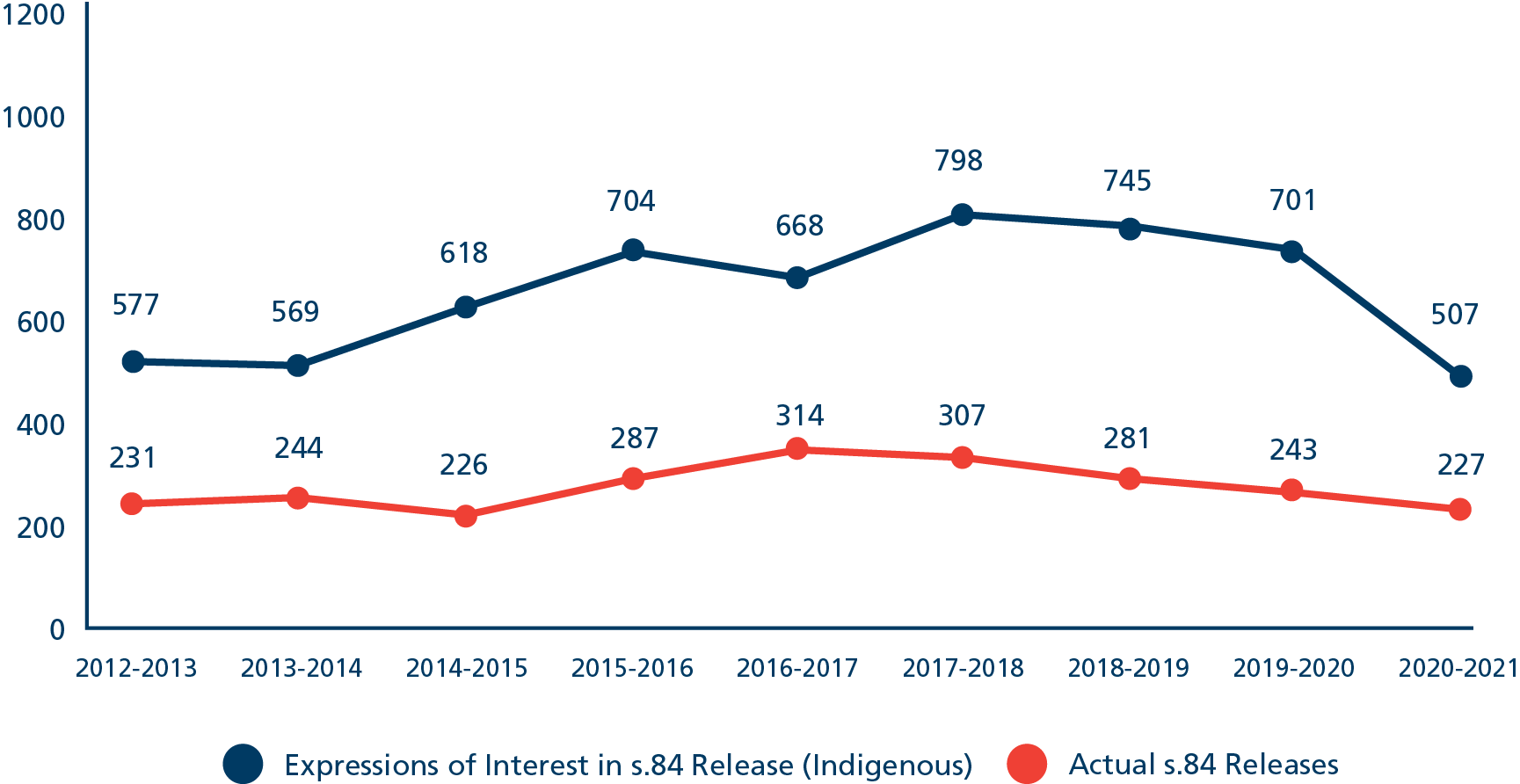

| TOTAL | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 15 | 27 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 183 |